The Untold Truth Of Manu Chao

Manu Chao is one of the most recognized musicians around the world, especially in Europe and Latin America. But in the Anglophone world, he's gone largely unrecognized. Of those English speakers who're familiar with his music, the album "Clandestino" is probably his best-known record. Eschewed early on by broadcasters because of its drug references, and carrying some strong anticapitalist vibes, it didn't receive a lot of marketing from its record label, Virgin. All the same, largely via word of mouth, it picked up a wide following and became a cult classic after staying in the French charts for four years and selling over five million copies worldwide!

Part of the reason why Chao's music fell under the radar in the English-speaking world may be the fact that his rise to fame coincided with the rise of "world music" as a genre label. An overly large umbrella term encompassing all music from non-English-speaking countries, it's now rightfully scorned as outdated and problematic.

However, perhaps ironically, if there's any musician this label actually fits, it might just be Manu Chao. Known for singing in a range of languages, with musical influences from several different countries, his uniquely punk attitude is characterized by an unwillingness to conform to any one culture or style. For his tendency to break so many of the conventions and boundaries most musicians adhere to, he's been described as "music's last true radical," and he's done plenty to earn that title.

He grew up inspired by revolutionaries

Like many musicians, Manu Chao's artistic influences go back to his childhood in Paris, and some of the first music he was exposed to as a child were songs from the Spanish Revolution. This was a workers' revolution that opposed the fascist dictator Francisco Franco during the 1930s. Fascism, however, would later triumph in Spain, eventually leading Chao's parents to flee the country just months before he was born.

Needless to say, antifascist sentiments remained strong in his family, and he mentioned in an interview with The Times, that one of his earliest childhood memories was a poster of the famous Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara which his parents kept pinned to their wall. With his father being a journalist, the family also regularly hosted political activists, both from Spain and from South American countries like Argentina, Chile, and Brazil. These strongly influenced some of Chao's best-known songs like "Malegria" and "Desaparecido."

Manu Chao also mentioned in an interview on NPR's Alt.Latino that his favorite musician as a child was the Cuban pianist and singer Bola de Nieve. De Nieve was also pro-revolutionary in Cuba, but he was subversive in other ways too. As a Black performer, he was part of the Afrocubanista movement in the early 20th century, using his music as a platform to challenge racism and societal rules.

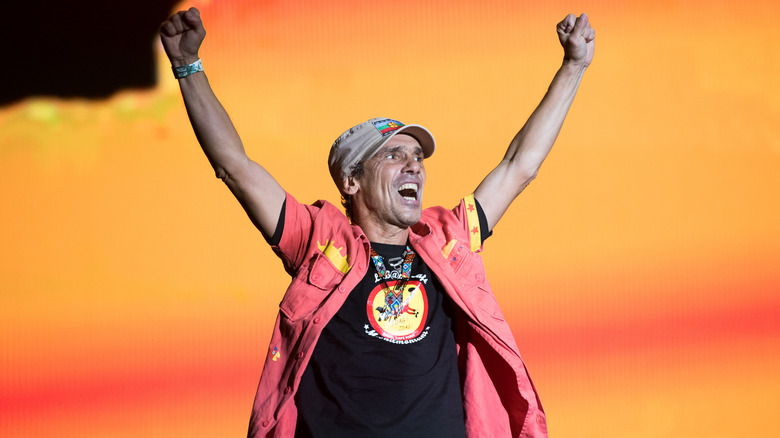

[Featured image by Jusezam via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

He's vocally anti-fascist

Unfailingly outspoken about issues of equality, Manu Chao has a stance of radical acceptance, embracing cultural differences and vocally opposing forms of oppression like fascism, racism, and capitalism. These themes often show up in his music, making connections between modern social movements with the struggles of the past and drawing on the long history of struggle against fascism in Europe. With his band Mano Negra, he made a point of touring other countries facing similar struggles, including Colombia, gripped for decades by the conflict between a left-wing insurgent group and far-right paramilitary forces.

Chao's firmly anti-fascist stance goes all the way back to his childhood, as a running tradition in his family. Under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco in Spain, his grandfather had been sentenced to death. This was the event that caused Chao's parents to flee to France shortly before his birth in 1961. For Chao, welcoming cultural differences is not simply a matter of social acceptance but also a political statement, showing up in the fusion of cultures which his music is famous for. As for his left-wing influence, he draws on a long legacy of activism in Europe which has often been overlooked in the modern world.

[Featured image by Derzsi Elekes Andor via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

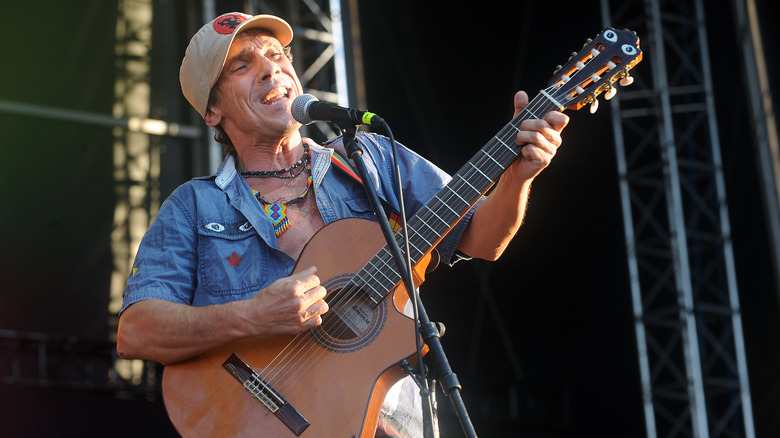

He's more of a busker than a rock star

There are plenty of buskers to be found on the streets of Paris. From the bridges near Notre Dame Cathedral to the corridors of the city's more spacious metro stations, many musicians can be seen giving street performances there, from young hopefuls to established performers. In his early days, Manu Chao was no exception. His band Mano Negra made some of their first performances in the stations of the Paris metro, playing an eclectic selection of music to the similarly eclectic crowds which passed by. Despite his fame, Chao has never lost his love of street performances, and he's still known for standing on street corners and spontaneously playing music for passers-by.

He's also well aware of the ill effects of fame, trying not to let his status go to his head. Keen to not put himself above others, he's been known to hire local buskers to join his band on stage during tours. It's all part of his effort to use his privileged position to help open doors for other musicians. He also clearly prefers the lifestyle of a busker or backpacker to that of a rock star. When the press asks for photos, he insists they pay for those taken by his friends rather than professional photographers, and when traveling he'd much rather sleep on a friend's floor than stay in a fancy hotel.

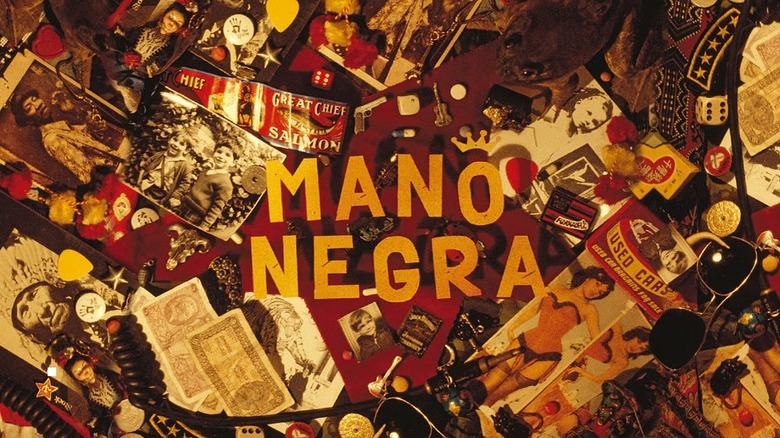

Mano Negra was named after a Spanish anarchist group

Manu Chao first became famous for performing with the band Mano Negra. Meaning "black hand," it was once the name of a group of Spanish anarchists. La Mano Negra was founded in the late 19th century in Andalusia, a large region of southern Spain. At their core, they were a rural workers' rights movement. Their aims were to bring down the government and aristocracy, with the ultimate goal of land reform and a change in the social order. Created as a secret organization, they gained a reputation for violence, being committed to using any means necessary to achieve their goals. Even extreme ones. Ultimately though, they saw this as simply a means to an end in their efforts to prevent the wealthy from abusing their power.

The name was later used for a group of Latino guerillas in a comic book, "Condor," written by Dominique Rousseau, and it was in this comic that Chao first heard the name. Ramón Chao, Manu's father and a political refugee from authoritarianism, was the one who explained the history and the significance of the name Mano Negra — noting also that the name "black hand" had previously been used by a Yugoslav militant group, as well as being a kind of witch from Gallician folklore. Manu later mentioned in interviews how he finds it interesting that the name has significance in many countries, including Colombia, where it was the name of a paramilitary group.

Mano Negra was not his first band

Most people know of Mano Negra as being Manu Chao's first band, but he was in more than one band previously. His introduction to music was in a low-key neighborhood band and, when he first started out, he wasn't a singer but a bass player. The group had trouble finding a vocalist though, so Chao's bandmates decided that he take on the role. It wasn't his choice, and he didn't even enjoy it at first but now feels grateful to his early bandmates for giving him the push.

Before forming Mano Negra, he was also in a few other bands, the first of which was heavily influenced by the U.K. punk scene. Chao was particularly inspired by the energetic performances of The Clash, who had a strong influence on many French musicians during the early '80s. The earliest bands Chao formed were called Joint de Culasse and Les Hot Pants. He later also performed with a band called Los Carayos, continuing to play with them for a while even after Mano Negra had gotten together. While Los Carayos never took off, several of its members would go on to also become leading figures in French rock music. Mano Negra though, was the first of Manu Chao's bands to see true success. Holding onto their influences from U.K. punk rock, they even went on to play as a support act for The Clash at London's Marquee.

He named his own musical genre

Mano Negra's first album was called "Patchanka," a word meaning patchwork, which fits the often chaotic combination of styles that have always defined Manu Chao's music. But it's also a little more than simply an album title. Patchanka was actually the name that Chao gave to his own musical genre. His distinctive sound started out as a blend of French, Spanish, and North African styles, combining elements of genres from ska-punk to salsa to flamenco to Algerian raï.

Ever since, Manu Chao's music has remained difficult to categorize, with critics often describing it using terms like "genre-defying." His influences have only continued to diversify too, later drawing influences from genres like cumbia, funk, reggae, and cabaret. Reflecting his borderless fusion of musical styles, Chao's vocals are almost hyperpolyglot in their sheer eclectic variety of languages. He most often sings in French or Spanish, but also includes languages like English, Galician, Arabic, and Wolof.

Journalist Vivien Goldman once noted that this inclusionary spirit and refusal to conform is an extremely punk attitude, tying together Chao's early musical influences with his multicultural background, and cementing his popularity across so many countries. His search for new influences to incorporate has been tireless too, making a point of looking far and wide. He's performed with a variety of Latin American artists and has found a lot of inspiration from street culture and local bars.

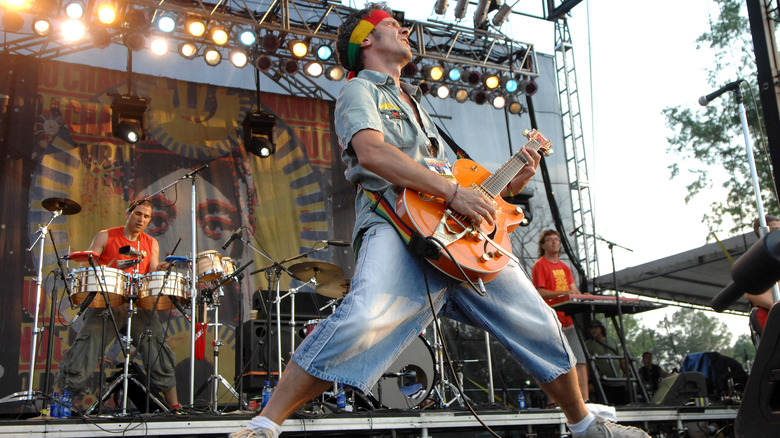

Radio Bemba Sound System was named for the Cuban Revolution

Mano Negra broke up in the early 1990s, Manu Chao made and released his first solo album, "Clandestino" with its uniquely catchy sound while traveling in Latin America, before heading back to Europe. Finding himself in the Spanish capital of Madrid, he spent time with a few local musicians and soon formed a new band, Radio Bemba Sound System. Around the same time, Chao began to move further away from the rock sound which had defined Mano Negra and his early musical career, but his music was no less radical. Much like Mano Negra, the name of Radio Bemba Sound System had a revolutionary inspiration.

The original Radio Bemba was an information network used during the Cuban Revolution. A flow of information was key during the revolution, both within the country and with the outside world. With a name meaning something like "rumor mill," Radio Bemba was a way for Cubans to stay up to date on how to get by from day to day. With a mixture of rumor and facts, it was used by famous revolutionaries including the legendary Che Guevara. The name is simultaneously a nod back to Chao's childhood inspirations and a statement about his revolutionary political ideas.

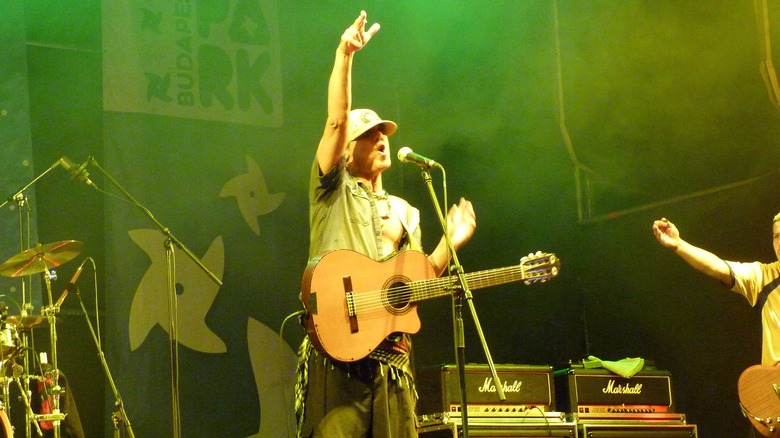

He likes to give impromptu performances

With worldwide fame, Manu Chao has played at some high-profile places. Among others, he's performed on the Pyramid Stage of the U.K.'s Glastonbury Festival and in Mexico City's Zócalo, the second-largest public plaza in the world. Refusing to let fame go to his head though, he maintains an exceptional amount of humility and is just as happy playing in low-key venues like small bars in Spanish cities. While on tour, between big concert dates, he's known for giving small impromptu performances to all kinds of audiences, including students, striking workers, and mental patients. Sometimes, he simply shows up to workers' protests with a guitar.

This is when he's playing at a venue at all, and not simply busking on the street. One place he can sometimes be seen playing in a bar in Barcelona is called El Mariatchi. It's the kind of place that definitely suits his vibe, for a few different reasons. The Mariatchi bar is a speakeasy, one of the first to open when squatters occupied disused buildings to turn them into underground drinking dens. Now a permanently established but easy-to-overlook bar, it's the kind of place where any night might see musicians show up and spontaneously start playing.

He was among the G8 summit protesters

In 2001, the G8 summit drew a huge protest. Uncomfortable with the idea of a small handful of political leaders making decisions that would impact the entire world, hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Genoa, Italy, to protest against imperialism and capitalist globalization. Standing in solidarity among the protesters was none other than Manu Chao. Particularly notable was the fact that he was outside playing music for the crowds protesting the summit, while other musicians like Bono and Bob Geldof were inside mingling with politicians.

Manu Chao has been outspoken about the problems of economic globalization and the increasing social inequality it causes. In an interview with the University of Southern California, he highlighted how this is connected with a host of other social issues like immigration, education, and organized crime. These are matters which have long been on Chao's mind. "Clandestino," arguably his most famous song, speaks about this kind of social issue directly, with lyrics comparing illegal immigration to the drug trade. As well as speaking up about the dangers of imperialism, Chao has also stood in solidarity with the Indigenous people most harshly affected by it.

He has no problem with pirated music

To say that Manu Chao is okay with pirated music feels like an understatement. If anything, he fully supports it. In an interview with Radio France Internationale, when asked his thoughts on pirate recordings, he replied simply, "Great!" It makes sense that Chao would be happiest with people freely sharing music, given his attitude toward capitalism. He previously described in an interview with Social Worker that today's world was like "living in a dictatorship of money." Accordingly, he's perfectly fine with thousands of buskers in Barcelona owning pirated copies of his music. Moreover, he's also dabbled in music piracy himself, having produced cost-price CDs of local artists' music for buskers to sell.

Pirated music has been a contentious issue ever since mp3 file sharing first became possible on the internet, with musicians divided over the issue. Several artists fully support file sharing though. Together with others like Moby and Courteney Love, Manu Chao is of the opinion that internet file sharing is only really detrimental to producers and record labels, while the musicians themselves make the bulk of their income from performances. Radiohead made its statement on the issue by releasing an album with a downloadable pay-what-you-want model, proving that musicians can get by without record labels even getting involved. Manu Chao has taken this one step further still, with his official website hosting several of his songs which are available for download completely free of charge.

He's a radical optimist

Optimism is radical, as Guillermo del Toro wrote in a 2019 Time op-ed. In a world so constantly consumed by cynicism, he made a compelling point, and Manu Chao has taken this message to heart. In an interview with The Independent, he mentioned how people in the deprived areas of Africa and South America keep a positive attitude as a coping mechanism. Speaking about himself, Chao remarked, "[T]he more I think about the problems of the world, I feel I have to be positive. I wouldn't like to fall into cynicism or nihilism. That's not in my nature."

This shows vividly in his music, which carries an undercurrent of optimism even when tackling serious social issues. It's perhaps most overt in the album title "Proxima Estacion: Esperanza" — meaning "Next station: Hope," it's a reference to a stop on the Madrid metro but also a statement about the brighter future and positive atmosphere that Manu Chao strives for.

Instead of trying to be a leader though, his aim is to create spaces where people can simply meet and talk. He's spoken before about how he tries to use his concerts to accomplish this, saying at his USC lecture, "I think we have to find a place where all communities join and try to live together. Our show is a little like that." Now, in the 2020s, with literary movements like Hope Punk putting ideas of radical optimism center-stage, Manu Chao's music is as relevant as ever.