False Things About The X-Men You've Been Believing

The X-Men are one of Marvel's most enduring franchises, rising to popularity in the late '70s and staying there for decades. There are all kinds of X-Men, from now-standard folks like Wolverine and Storm to more out-there characters like walking wax-man Glob Herman. Together they've been the source of nine blockbuster movies, multiple animated series, and, of course, thousands of comic books.

With that much material, however, it's almost impossible to know everything about Marvel's Merry Mutants. Even if you're a die-hard fan with a love of trivia, even if you know Admantium from organic steel and the M'Kraan crystal from ruby quartz, something's bound to slip through the cracks. We're here to help, though, with a list of false things you may have been believing about the X-Men. Read on, and next time you get called out on a mistake, you won't have to blame it on Charles Xavier planting false memories.

The Uncanny Mutants

More casual readers might look at a team of heroes gathered together by a guy who calls himself Professor X and assume that Charles Xavier named his team after himself. If you dig a little deeper, though, there's a slightly less egocentric reason for the name: In the pages of their very first adventure, Xavier mentions that the X-Men are named for having "X-tra" abilities that non-mutant humans don't. It's not very convincing from the guy who also named a school after himself, but we'll just have to take his word for it.

Except that it's not the actual reason the team got their name. In real life, Lee and Kirby wanted to give their book the simple, straightforward title The Mutants. Lee recently revealed, though, that when they presented the idea to Marvel publisher Martin Goodman, he liked the idea, but not the name. Goodman was worried that superhero fans wouldn't be familiar with the word "mutant," telling Lee "our readers, they aren't that smart" and requesting a change.

Looking back, it's pretty easy to give Goodman the credit for being right on this one, but we're left with the same question Lee had once he got his new title approved: "If nobody would know what a mutant is, how will anybody know what an X-Man is?"

Original creations, do not steal!

Superpowered misfits who protected a society that hated and feared them! Abilities that could be as much of a curse as they were a benefit! Evil forces gathering against them in a group known as the Brotherhood! A mysterious leader in a wheelchair who would eventually be revealed to have complex machinations of his own and more than his share of secrets! When the X-Men hit the stands in 1963, those elements ensured that readers had never seen anything like this before! Unless, of course, they were reading DC Comics a few months earlier.

See, Uncanny X-Men #1 debuted in September 1963. In June of that same year, however, Marvel's Distinguished Competition published My Greatest Adventure #80, introducing the world to a team called the Doom Patrol. Made up of outcasts from society — including a racecar driver who was so badly injured that his entire body was replaced with a robot, a sci-fi mummy who could project his radioactive shadow out of his body for 60 seconds, and a 50-foot actress — the Doom Patrol fought the strange crimes of the Brotherhood of Evil and were led by the Chief, a mastermind in a wheelchair who had gathered them all together.

Sound familiar? Yeah. While Arnold Drake and Bruno Premiani's Doom Patrol stories hit the shelves first, there's been a lot of debate over who ripped off whom, or whether it was all a coincidence. In an interview, Drake even went as far as saying he was "more and more convinced that [Stan Lee] knowingly stole the X-Men from The Doom Patrol." Despite their early similarities, however, the two teams would take some wildly divergent paths as they continued — and unfortunately for the Doom Patrol, the X-Men would absolutely become the more popular version of that idea.

They were an instant success

The X-Men are one of the most massive franchises in comics. It's spent decades at the core of the Marvel Universe, brought characters like Wolverine and Deadpool into the spotlight, and when the second ongoing X-Men title was launched in 1991, it broke records by selling over 6 million copies. With its huge prominence in pop culture, it's easy to believe Marvel's merry mutants were destined for greatness from the start. Unfortunately, that wasn't the case.

When The Uncanny X-Men debuted, Marvel Comics was riding high on the success of a string of hits that started with Fantastic Four and continued with Spider-Man. Unfortunately, not everything worked out so well. Even Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's first attempt at The Incredible Hulk, for instance, only ran for six issues. X-Men, on the other hand, was never actually canceled, but it sure did come close. Despite starting off with Lee and Kirby at the helm and what seemed like a foolproof formula for success built on combining the team dynamics of FF with a cast of Spidey-esque superpowered teens, the new title never caught on.

In 1970, X-Men #66 became the last issue of the series to feature new stories, and seemed like it would be the last issue, period. Eight months later, however, the series returned (perhaps because of the popularity the Beast was seeing elsewhere), but without new stories. Instead, the next 27 issues were reprints. Fortunately for X-Fans everywhere, though, Marvel decided to give the mutants another shot in 1975, relaunching the title with Giant-Size X-Men #1 with a new cast and a new direction, and found themselves with one of the biggest hits in superhero history on their hands.

The civil rights inspiration

One thing you often hear from casual X-Fans is the franchise was originally created as a metaphor for the civil rights struggle of the '60s. (Professor Xavier was inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., and Magneto by Malcolm X, etc.) If you really look at comics, though, making that connection usually signals a poor understanding of the X-Men, and probably a poor understanding of Dr. King and Malcolm X, too.

To be fair, the metaphors for the civil rights movement, as well as modern issues of equality, do exist as a central part of the X-Men today and have for several decades. It's an easy leap to make, too, with the hatred and fear of differences as an allegory for racism when you're dealing with obvious mutations like Nightcrawler or Beast, and with more subtle mutations in stories about mutants "coming out" that resonate with the LGBT community. Some of the most memorable X-Men stories have involved those themes, like the religious intolerance seen in God Loves, Man Kills and the dystopia of internment camps in the classic "Days of Future Past."

But those ideas were added into the X-Men well after they were created. While we associate a lot of those ideas with the cultural upheaval of the '60s, the X-Men of 1963 were definitely not meant to incorporate those ideas. Instead, mutants were just a convenience of storytelling, in that they were heroes that Lee and Kirby didn't have to make up origin stories for. As for Xavier and Magneto, it should be noted that Dr. King never started an extra-governmental paramilitary strike force under the guise of a school, and that Magneto's political motivations (and his status as a Holocaust survivor) weren't part of his original character either. Xavier has often been written as seeking peaceful coexistence, and Magneto was written from the start as having relatively sympathetic goals for a "supervillain," but likening them to real-life civil rights leaders is at best painting them with the broadest possible strokes, and at worst is dismissive of the work they did.

Jean Grey was the Phoenix

The Phoenix Saga is the X-Men story. It's arguably the central touchstone of the entire franchise, telling the story of Jean Grey being possessed with a cosmic power that corrupted her and led her to destruction on a planetary scale. Eventually, after destroying an entire planet and murdering its entire population to satiate the Phoenix's endless hunger, Jean was put on a trial and killed. Sort of. Not really. See, the real Jean never did all that stuff at all, since she was busy being in a coma at the bottom of the Hudson River.

This one gets a little complicated, but here's the short version: Chris Claremont and John Byrne's original plan for the ending of the Phoenix Saga was to have the Phoenix "locked away" in Jean's mind, with Jean returning to Earth, depowered. Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter, however, insisted that after killing a billion aliens, Jean had to die, and that was that. Years later, though, a series called X-Factor was in the works that would reunite the original five X-Men. Marvel needed to revive Jean, but also to separate her from her cosmically genocidal past.

The solution? The Phoenix wasn't Jean and never had been. In the pages of Fantastic Four, Byrne revealed that when Jean was "resurrected" as the Phoenix the first time, after crashing a space shuttle into the Hudson River, it was actually just the Phoenix Force itself taking Jean's form, along with her memories. The real Jean had been down there in a cocoon for years, until she finally emerged, perhaps ironically, like a phoenix. Of course, over the years, the Phoenix Saga's status as the most beloved X-Men story ever meant the Phoenix would be tied to the real Jean eventually, too.

'Real name: Logan'

If you grew up getting most of your information about the X-Men from trading cards in the '90s, then you know three things about Wolverine for sure: His bones and claws are laced with an unbreakable metal called Adamantium, he was a product of the sinister Canadian super soldier program called Weapon X (one of the few times that the words "sinister" and "Canadian" are written next to each other), and his real name is Logan.

The good news is that the first two are still pretty accurate, but the third one could use some updating. In 2001, Marvel decided to make Wolverine's mysterious past a little less mysterious with a miniseries accurately titled Origin. It revealed that Wolverine was actually James Howlett, who grew up as the sickly son of an extremely wealthy family. Little Jim was, of course, a mutant, but his powers manifested as the result of his father being murdered in front of him, trauma that sparked the first of many memory issues. Also, owing to the all-consuming power of coincidence, he spent his childhood in love with a girl who bore a striking resemblance to Jean Grey, and being picked on by a bully that looked a whole lot like Sabretooth.

While he still prefers "Logan" — actually the name of the senior Howlett's murderer, who may also be Wolvie's biological father — Wolverine acknowledged his real name once all of his missing memories were restored.

Creating international X-Men from scratch

When Giant-Size X-Men #1 hit stands in 1975, Len Wein and Dave Cockrum relaunched the franchise and gave readers a version of the X-Men that was unlike anything they'd ever seen before. Rather than being teenagers at a boarding school for people with mysterious powers — like that would ever catch on — this was a slightly older cast that gave the X-Men an international flavor. Cyclops and Marvel Girl were joined by the Native American Thunderbird, the Japanese hero Sunfire, an obscure Canadian Hulk villain called the Wolverine, and three brand-new characters: Colossus from the Soviet Union, Storm from Kenya, and Nightcrawler from Germany.

The new heroes fit in so well that it's easy to believe they were created specifically to fit that new cast of international X-Men, but that wasn't actually the case. Storm, Colossus, and Nightcrawler had their start as characters Cockrum designed for DC's Legion of Super-Heroes.

Cockrum had been the artist on Legion, a book about teenage superheroes set in the distant future, when he pitched a spinoff about a group called "The Outsiders." The heroes were rejected by DC, so when he got the job to introduce a new team of X-Men, Cockrum recycled his ideas. While Storm and Colossus were changed significantly — really only taking design elements from Cockrum's Outsiders pitch — Nightcrawler was transported from DC's 30th Century to Marvel's 1975 almost completely unchanged.

A true (and literally) blue X-Man

While they're often overshadowed by later additions like Wolverine, the original five X-Men will always be the ones who were there when everything started. They will always be identified first and foremost with the X-Men! Unless they spent 20 years hanging around in completely different corners of the Marvel Universe, that is.

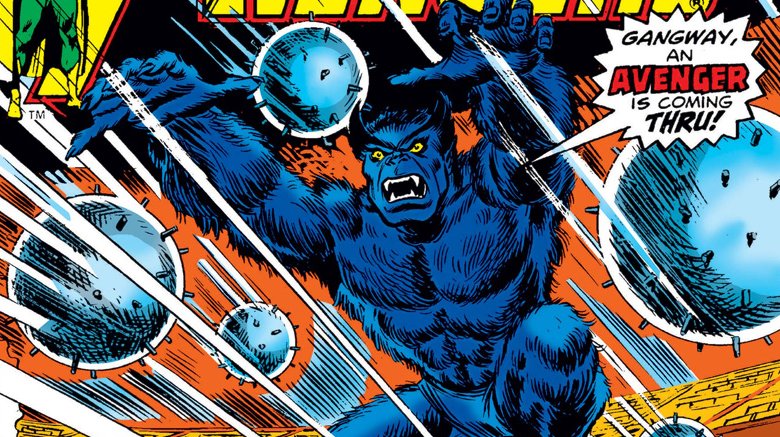

That's what happened with Hank McCoy, better known to superhero fans as the Beast. While the original X-Men comic itself was never that popular, Beast was the most successful character by far. Fans loved the combination of his monstrous looks and genius intellect with a more fun-loving attitude than characters like the Hulk or the Thing, and by the late '60s, the Beast had bounced into solo adventures in the pages of Amazing Adventures. Before long, he had joined up with the Avengers, where he would develop a friendship with Wonder Man that would define his character for a decade, and also spend some time on the Defenders. It wasn't until 1991 that he returned to the X-Men.

Of course, while he's the most successful, he's not the only original X-Man who abandoned what looked like a sinking ship. While Cyclops and Marvel Girl would remain with the team through the 1975 relaunch, Iceman and the Angel wound up in the Champions alongside Hercules, Ghost Rider, and Black Widow, one of the most random teams in Marvel history. Not exactly the prestige of the Avengers.

Cable's complicated family tree

Cable is tough to explain at the best of times, so you can be forgiven if you choose to accept the simple explanation that he's Cyclops and Jean's son from the future. That's good enough (and complicated enough) for most people, but it's also not quite true.

The actual answer? Well, while Jean was presumed dead because her cosmic alien clone body killed itself on the Moon, Scott Summers met (and married) a woman named Madelyne Pryor, who looked almost exactly like Jean. The reason for that resemblance was, of course, that she was a clone of Jean created by Mr. Sinister. She got pregnant and gave birth to Nathan Summers, who was infected with the techno-organic virus and sent to the future to be raised by Mother Askani, who actually was Scott and Jean's daughter Rachel, but from a different future. She also brought Scott and Jean to the future to raise him, which they did under false names, spending years in the future before returning to the present day after mere moments. Then Nathan changed his name to Cable (nobody's quite clear on why) and came back to the present, where he was eventually murdered by a younger version of himself from another timeline.

So, you know. Pretty simple stuff by X-Men standards.

Wolverine was always the most popular character

The X-Men franchise contains some beloved characters, but there's no question at all about who's the most popular: It's easily Wolverine, who clawed his way to the top to become a pop culture icon.

That wasn't always the case, though. When Len Wein and Herb Trimpe introduced Wolverine in the pages of Incredible Hulk #181, they had no real intentions beyond just filling an editorial mandate to give the Marvel Universe a Canadian superhero. Trimpe would even refer to him as "one of those secondary or tertiary characters" that was used "with no particular notion of it going anywhere," much like other mid-'70s Hulk adversaries like the Missing Link, the Man-Beast, or the Cobalt Man. When an international team of X-Men was created a few months later, Wolverine seemed like a natural fit alongside other pre-existing characters like Sunfire and Banshee, even though artist Dave Cockrum wasn't really a fan of the character.

Even in those early X-Men stories, though, Wolverine's not really the focus — those stories mostly revolve around Cyclops and Storm. While Wolverine has an alluring mysterious past that's doled out piece by piece — readers weren't even sure that the claws were part of his arms and not just weapons until a year into his tenure as an X-Man — he's an ensemble player until Uncanny X-Men #132 in 1977. That was the story where Wolverine stepped into the spotlight, and he hasn't left it since.