OceanGate: 14 Facts About The Company With The Titanic Sub

There's something fascinating and more than a little terrifying about the ocean's vastness – what Jules Verne referred to as "the 'Living Infinite'" in his classic novel "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea." Since humanity's earliest days, the ocean has beckoned, luring us forth with its bountiful fish, mermaids, and promises of new lands and riches. Astride our increasingly sophisticated seafaring vessels, we have seemingly conquered this final earthly frontier – though, in fact, over 80% of the ocean remains shrouded in mystery and we know more about space than we do about Earth's seas.

Most people are content to let the ocean keep its secrets. But some intrepid souls seek to explore this last uncharted realm – and they are rarely content with its surface. One such company, OceanGate, aspired to probe the deepest reaches of the ocean. And, what's more, it wanted to open these underwater zones to everyone by way of manned deep-sea submersibles. It was a noble venture, but, as many pointed out, it came with significant risks.

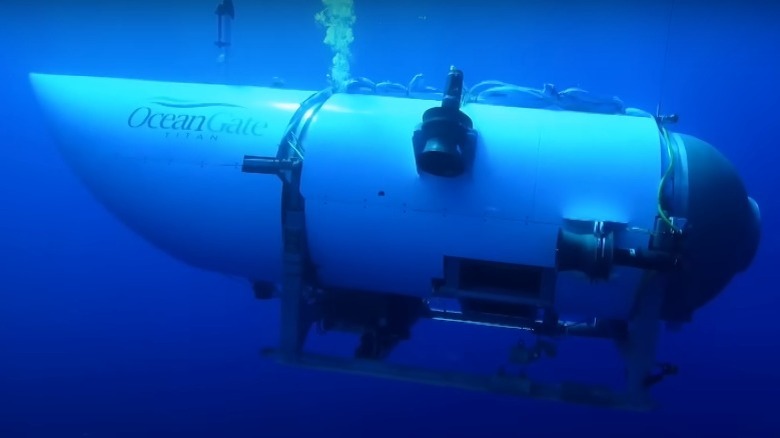

In June 2023, humanity was reminded of the dangers of deep-sea voyaging when OceanGate's Titan submersible and its crew of five went missing while exploring the wreck of the Titanic. The ensuing search captivated the world for days until Titan's fractured remains were found scattered on the ocean floor, all five on board dead. In the wake of the tragedy, many were left wondering: What is OceanGate, anyway? Here are 14 facts about the ambitious seafaring company that created the Titan submersible.

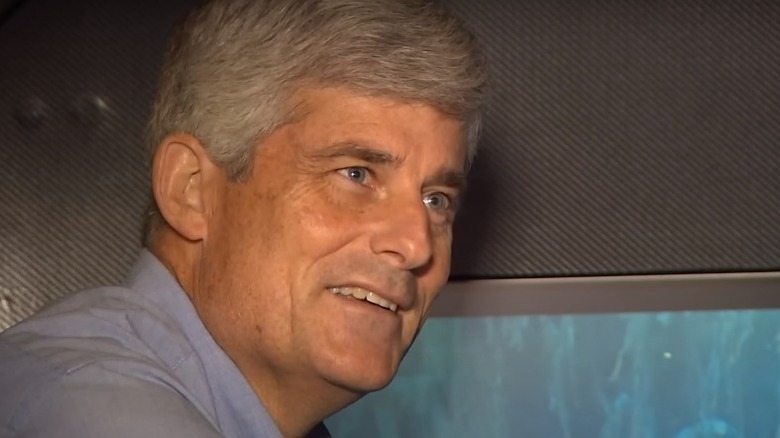

CEO Stockton Rush was originally interested in aviation and space travel

OceanGate's CEO, Stockton Rush, was an adventurer from the very start. As a child, he loved "Star Trek" and always dreamed of going to space. Somehow, his wealthy father even arranged for him to meet a real-life astronaut – Pete Conrad – who encouraged him to get his pilot's license if he wanted to pursue his dream. Young Rush took that advice to heart. At just 18, he became one of the world's youngest commercial pilots in 1980.

Unfortunately, his dream was short-lived. Issues with his eyesight excluded him from becoming a military pilot, which simultaneously disqualified him from becoming an astronaut. Though he would never go to space, Rush was far from done with risky adventuring. He put his elevated math skills to good use at Princeton University, earning an aerospace engineering degree and designing an experimental high-speed ultralight aircraft for his thesis.

Following college, he worked as a fighter jet flight-test engineer, earned an MBA in business, and invested in several tech companies. He found his way to the rain-dampened Seattle area of Washington State – a land brimming with aquatic opportunities. Before long, Rush realized that there were other unmapped regions to discover right here on Earth. "I was interested in exploration," he told Princeton Alumni Weekly in 2017. "I thought it was space exploration, I thought it was "Star Trek" and "2001: A Space Odyssey" and "Star Wars"...and then I realized, it's all in the ocean."

OceanGate's goal was to facilitate ocean exploration and tourism

Stockton Rush had been scuba diving since he was a teen. But, in western Washington's frigid waters, he became disenchanted with the uncomfortable cold-water gear and bulky tanks he had to contend with on underwater forays. Surely, there had to be a more comfortable way to enjoy the deep. Submarines were the obvious answer. As he explained to Smithsonian Magazine in 2019: "Being in a sub, and being nice and cozy, and having a hot chocolate with you, beats the heck out of freezing and going through a two-hour decompression hanging in deep water."

There was just one problem: submarines – and submersibles, their less self-sufficient cousins – were in short supply. As Rush quickly learned, very few were available for general recreation and even buying one proved difficult. Eventually, he built his own one-person submersible using a kit and blueprints in 2006. He was instantly hooked – and saw a major business opportunity to boot.

In 2009, he and his business partner, Guillermo Söhnlein, launched an underwater exploration company called OceanGate with the goal of hosting a fleet of manned submersibles that anyone could use for research, resource prospecting, or tourism – for a price, of course. According to Söhnlein in a 2023 interview with Sky News, OceanGate's original mission was to "open the oceans for all of humanity." After all, as an incredulous Rush asked Smithsonian Magazine: "If three-quarters of the planet is water, how come you can't access it?"

The company has surveyed and discovered underwater wrecks

OceanGate purchased its first submersible, Antipodes, in 2009 – the same year the company started. The fully-certified bright yellow vessel had a long history as a working diver lock-out craft turned tourist sub, and was well-versed with over 1,300 completed dives. Outfitted with a giant viewing dome and able to take up to five people down to depths of 1,000 feet, Antipodes was quickly put to use exploring previously unreachable underwater sites.

In 2012, OceanGate divers in Antipodes investigated a 100-foot anomaly resting 240 feet below the waves off the coast of Miami, Florida. It ended up being a wreck of a World War II-era Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter plane, a completely new discovery that the company then documented with photos, videos, and scans. They donated their findings to Washington, D.C.'s U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command, making protection and future studies of the site possible.

OceanGate has also used its submersibles to examine known but hard-to-reach shipwrecks. In 2011, Antipodes investigated and photographed the 90-year-old remains of the SS Governor, a passenger liner resting at the bottom of Washington's Admiralty Inlet where fast currents, depth, and proximity to shipping lanes have combined to make it inaccessible to most. Then, in 2016, OceanGate surveyed the wreck of the famous Italian luxury liner SS Andrea Doria, which sank off the Massachusetts coast in 1956, using its newly-outfitted Cyclops 1 submersible. Data from these expeditions will be used to create a 3D rendering of the site.

Biologists used its submersibles to study marine life

After completing their first tourism dives, OceanGate identified another great use for their submersibles: marine biology studies. "People would ask me about a fish, and I wouldn't know anything about it," CEO Stockton Rush explained to Smithsonian Magazine in 2019. So, to make for a better tourist experience, he started bringing biologists along to act as tour guides. It was the start of a beautiful relationship.

By 2013, OceanGate was surveying several artificial reef systems off the coast of Miami, Florida, for the presence of invasive lionfish. There, they made a startling discovery: not only had lionfish spread to the reef, but they were found at greater depths than originally thought possible. Researchers used data from the dive to examine the population density, behavior, and distribution of the problematic fish – something that could not have been accomplished without an underwater vessel.

OceanGate then undertook several other biological missions at depths conventional divers couldn't reach, including capturing video of elusive deep-dwelling six-gill sharks and hosting a survey of Washington's Salish Sea, which allowed biologists to study Pacific sand lance and red urchins firsthand. "We came down through clouds of spotted ratfish," fish biologist Adam Summers told KUOW of the voyage. "Then these schools of fish would come through...As a fish biologist, I was just in heaven seeing these things in their schools – in their native environments – instead of in nets. I was just blown away to see them as they lived."

OceanGate's launch and retrieval platform was a great invention

Much like SpaceX attempting to make space travel more affordable, OceanGate sought ways to cut the cost of its underwater voyages. But because submersibles are not fully autonomous like submarines, they rely on a support ship to travel to dive sites and function while at sea. Support ships must be equipped with specialized infrastructure like cranes to hoist the heavy submersibles into and out of the water. And, as you might expect, chartering such a ship isn't cheap.

Luckily, OceanGate found a nifty workaround. Inspired by the Hawaii Undersea Research Lab's similar design, they constructed a patented launch and retrieval platform they dubbed Ms. Lars – for Mobile Subsea Launch and Recovery System – that could be lowered 32 feet into the water by filling up a series of flotation tanks, allowing submersibles to launch below the turbulent surface. When the voyage is over, the submersible simply returns to the launchpad and is raised up by emptying the pad's tanks.

Ms. Lars is easily towed behind most ships, eliminating the need for a specialized support vessel. It also functions without the assistance of divers, making it safer. "This patented launch sled is very cleverly designed and seems to work very well," expert submariner Aaron Amick said on his YouTube channel, Sub Brief. "It allows them to operate in higher sea states than if they were just going off the back of a deep-sea ocean vessel because they don't need an A crane."

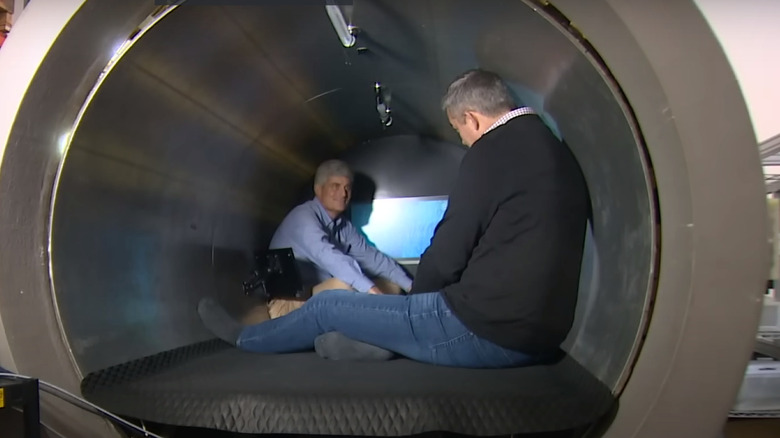

The Titan submersible featured a novel carbon fiber hull

Just a few years after starting the company, OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush began researching ways to streamline his craft's designs to reach the sea's most remote regions. In a 2019 interview with Smithsonian Magazine, he described this desire to delve ever deeper as "the deep disease." Owing in large part to his aerospace engineering background, Rush zeroed in on carbon fiber as a possible solution.

Commonly used to construct airplane wings and propeller blades, carbon fiber composite consists of a many-layered tight mesh of uniform fibers. It is stronger than steel, yet weighs considerably less. To Rush, it seemed to be the perfect material for a submersible hull, as it would be less bulky than the typical metal and foam construction, making for a craft that was faster, easier to maneuver, and cheaper to build. There was just one problem: it hadn't ever been done before.

Only one person – marine engineer Graham Hawkes – had designed a carbon fiber submersible hull, and he died before ever getting it in the water. Finishing what Hawkes started, Rush hired the same company, Spencer Composites, to build a cylindrical carbon fiber hull for his third submersible, Cyclops 2, which was later renamed Titan. From the start, many questioned the unconventional design. "This is not exactly what, in my opinion, would be innovation," Duke University engineer Rachel Lance later told CNN. "Because this is already a thing that has been tried and it simply didn't work."

The company fired an internal whistleblower

The development of OceanGate's third submersible, Titan, was rocky from the start. The company was already venturing into uncharted waters with its unconventional carbon fiber hull design. Add to that the fact that CEO Stockton Rush intended his latest craft to probe depths of up to 13,000 feet – over 11,000 feet deeper than any of OceanGate's other submersibles had gone — and you have, at best, a rather challenging design process and, at worst, the potential for catastrophe.

OceanGate's former director of marine technologies, David Lochridge, first voiced concerns about Titan's safety in a January 2018 inspection report. According to a U.S. District Court document, Lochridge had expressed apprehension about the lack of adequate stress testing of the carbon fiber hull, the vessel's window only being rated for about one-third of its intended dive depth, the potential for unmonitored tears to form in the hull due to repeated high-pressure dives, the use of "hazardous flammable materials" in its construction, and the craft's overall capability to "subject passengers to potential extreme danger in an experimental submersible."

Rather than address these alarming concerns, OceanGate first fired Lochridge, who had worked at the company in some capacity since 2015, then sued him. But Lochridge wasn't alone. As CNN reported, a second employee who worked as an operations technician at OceanGate in 2017 resigned over dismissed concerns regarding the carbon fiber hull's inadequate thickness and potential for failure. He added that many other OceanGate staff members shared these concerns.

Ocean exploration experts expressed concerns about Titan

In March 2018, just two months after OceanGate employee David Lochridge was fired for voicing safety concerns about Titan, several oceanographers, deep-sea submersible experts, and industry leaders echoed his misgivings. In fact, an assembly of 38 experts sitting on the Manned Underwater Vehicles Committee of the Marine Technology Society was so worried about OceanGate's new vessel that they took it upon themselves to compose a signed letter to CEO Stockton Rush, essentially asking him to rethink expediting the development of his newest creation.

In the letter, obtained by The New York Times, the experts voiced their "unanimous concern" with Titan's untested design ahead of OceanGate's planned expeditions to the Titanic wreck, which rests about 12,500 feet below the sea. "Our apprehension is that the current 'experimental' approach adopted by OceanGate could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic)," the committee wrote. Like Lochridge, they called for adequate testing, outside inspections, and certifications, writing: "It is our unanimous view that validation by a third party is a critical component in the safeguards that protect all submersible occupants."

As the BBC reported, submersible expert Rob McCallum emailed Rush multiple times that same month, also calling for outside testing and certification of Titan and expressing concerns about Rush's seemingly reckless process. "As much as I appreciate entrepreneurship and innovation, you are potentially putting an entire industry at risk," he wrote. "In your race to Titanic, you are mirroring that famous catch cry: 'She is unsinkable.'"

Stockton Rush believed that safety regulations stifled progress

OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush made no secret of his distaste for regulations, certifications, or anything he considered needless bureaucracy, claiming on multiple occasions that such institutions hindered innovation. "[The commercial submersible industry] is obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations," he told Smithsonian Magazine in 2019. "But it also hasn't innovated or grown — because they have all these regulations."

Instead, Rush did everything in-house, patenting safety systems and testing new submersibles himself. But some found this behavior reckless — if not outright dangerous. For example, OceanGate's safeguard against pressure damage to Titan's hull relied on a sensor system listening for cracking and popping sounds, which experts warned might only be audible milliseconds before implosion. What's worse, such sounds had already been heard emanating from Titan's hull during operation. Submersible expert Karl Stanley reported hearing loud sounds consistent with a weakening hull on a 2019 dive, and Rush admitted to David Pogue in 2022 (via CBS) that early test dives often got pretty noisy.

Despite all the opposition, Rush maintained that his way of doing things was working just fine. "At some point, safety just is pure waste," he told Pogue. "I mean, if you just want to be safe, don't get out of bed, don't get in your car, don't do anything. At some point, you're gonna take some risk, and it really is a risk/reward question. I said, 'I think I can do this just as safely by breaking the rules.'"

The Titan submersible had been to the Titanic wreck before

As OceanGate gained a reputation for touring shipwrecks, it was only a matter of time before CEO Stockton Rush made plans to visit the most famous one of all. "There's only one wreck that everyone knows," he explained to Smithsonian Magazine in 2019. "If you ask people to name something underwater, it's going to be sharks, whales, Titanic." The only question that remained was if the Titan submersible — with all of its potential issues — could endure a dive nearly 2.5 miles below the sea.

Titan successfully reached the Titanic wreck for the first time on July 10, 2021. The company vowed to return each year to scan, photograph, and document the site — and, of course, take paying customers along for a fee. OceanGate began selling tickets to its premiere attraction in 2017, while its star vessel, Titan, was still in development. The original cost of admission was a cheeky $105,129 — the price of a 1912 first-class Titanic ticket adjusted for inflation. By 2020, it had increased to $250,000.

The Titan made 13 voyages to the Titanic in 2021 and 2022, but they were not without incident. On one, the submersible got stuck on the seafloor, and the crew was trapped in the vessel for five hours. On another, it completely lost communications with its support ship while suffering a dead battery. And, perhaps most terrifyingly, it once spun around in circles underwater due to a thruster that had been installed backwards.

Stockton Rush engaged in some shady business practices

OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush was known to resort to several less-than-savory measures to ensure the success of his business. But that's not too surprising when you consider that he's the same man who once told vlogger Alan Estrada that his personal ethos was: "You're remembered for the rules you break." According to Rolling Stone, OceanGate's finances were dicey at best, and its income seemed to come primarily from outside foreign investors.

Even shadier, the company's affiliated nonprofit — The OceanGate Foundation — lacked an independent board and was essentially run by Rush and his wife, a big no-no in the nonprofit world. OceanGate also ran a subsidiary based in the Bahamas, something investigative journalist David Cay Johnston told Rolling Stone was a tad suspicious as it could be a way to avoid the United States' strict regulations regarding commercial vessels. The company was also involved in two lawsuits related to unissued refunds for canceled Titanic trips.

In addition, Rush used questionable recruitment tactics. In text messages shared to the media by Jay Bloom – a hesitant potential customer with safety concerns — Rush could be seen pressuring Bloom to join a Titanic tour at a discount. As Bloom later told People, he even declared it "safer than crossing the street" at one point. "He drank his own Kool-Aid, and there was just no talking him out of it," Bloom told People. "I don't think Stockton understood the risk himself, or didn't want to understand the risk."

OceanGate had plans to create more deep-sea submersibles

CEO Stockton Rush had big plans for OceanGate, and they certainly didn't end with Titanic expeditions. According to a 2017 interview with Composites World, he aspired to build up to 20 more vessels identical to the Titan, contingent on demand. At that time, he was also already designing Cyclops 3, 4, and 5 submersibles, which would all feature carbon fiber hulls, and which he planned to take down to even greater depths.

In a 2020 press release, OceanGate announced that it would be designing at least one of these new Cyclops submersibles with NASA, an arrangement that would allegedly ensure that the vessel would safely attain its intended depth of 19,800 feet — nearly four miles below the sea. At the 2022 GeekWire Summit (via GeekWire), Rush already had his sights on another famous shipwreck — the German warship Bismarck — which lies at a depth of 17,500 feet.

He also discussed plans to eventually survey deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which are underwater biological hotspots characterized by volcanic activity and superheated water. In other words, a totally safe environment for a submersible. In a 2019 interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Rush — sounding a lot like the aquatic version of Elon Musk — alluded to even loftier goals. "We're going to colonize the ocean long before we colonize space ... Why leave? The ocean is a very protected environment. It's safe from ozone radiation, nuclear war, hurricanes. The temperatures and currents are very stable."

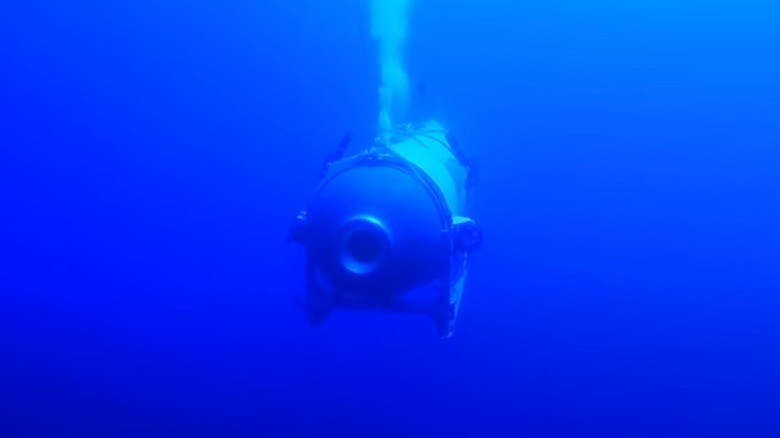

The Titan submersible imploded during a dive to the Titanic

On June 18, 2023, almost two hours into its 14th dive to the Titanic shipwreck, OceanGate's Titan submersible lost contact with its support ship, the Polar Prince. Five people were on board: OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, French Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet, British businessman Hamish Harding, and Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son, Suleman Dawood.

When Titan failed to resurface at the planned time, crew members on board the Polar Prince reported it missing. A weeklong search ensued, with multiple agencies scouring the North Atlantic for any signs of the vessel. On June 22, U.S. Coast Guard officials confirmed that a debris field had been found on the sea floor just 1,600 feet from the Titanic's bow. According to Coast Guard Rear Admiral John Mauger at a press conference (via CNN), the discovery suggested a "catastrophic implosion" of the vessel, meaning it had collapsed inward.

The U.S. Navy confirmed that it had heard a likely implosion on June 18 in the area where the Titan was diving around the time it lost contact. If the submersible was near the Titanic, it would have been subjected to almost 6,000 psi of water pressure – about 400 times that of sea level. "Implosions, like explosions, are very violent," physics professor Arun Bansil explained to Northeastern Global News. "As the hull breaks apart under the huge external pressure, a large amount of energy is released, and the five occupants would have died instantly."

OceanGate may be held liable for the deaths of Titan's passengers

As of June 2023, investigations into the Titan submersible's demise are still underway. Several pieces of the vessel – and possible human remains — have been retrieved from the sea floor for analysis to determine what exactly went wrong. OceanGate, meanwhile, has closed its doors and wiped its website.

Maritime lawyers claim that OceanGate's waiver, which warned passengers of the vessel's experimental design, may not be enough to protect the company against lawsuits from the passengers' family members if "gross negligence" is found — and there's already a mounting case for that. Speculation is rife into what exactly failed on the Titan. Experts are primarily focused on the carbon fiber hull, which could have succumbed to cyclic fatigue damage from repeated dives, as well as the craft's cylindrical shape, which distributed pressure loads unequally and likely resulted in weak points around its midsection.

CEO Stockton Rush also had a penchant for cutting costs. According to a U.S. District Court document, he avoided financing external testing and also declined to pay more for an acrylic window rated for the appropriate lower depth. What's worse, former Titan passenger Arnie Weissmann claimed in Travel Weekly that Rush admitted to getting Titan's carbon fiber at a discount because it was past its shelf life. He was also repeatedly warned of catastrophe. As director and deep-sea expert James Cameron told Reuters: "Now there's one wreck lying next to the other wreck for the same damn reason."