Tragic Stories About Tennessee Williams

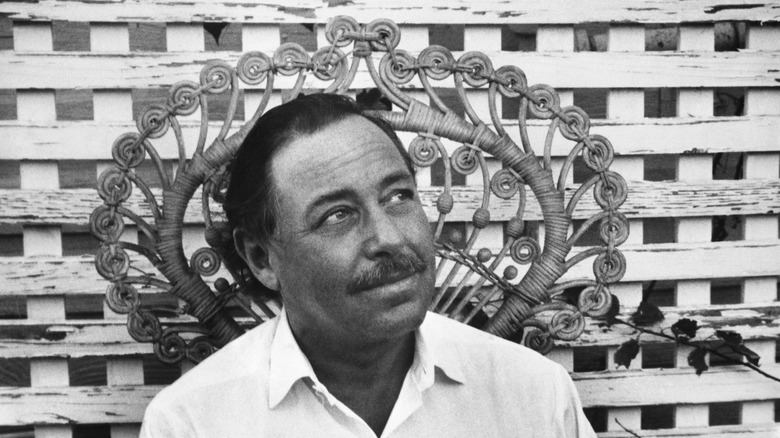

Debonair southern gentlemen Tennessee Williams was without a doubt one of America's greatest playwrights; a man who explored the difficult lives of ordinary people with remarkable compassion and insight. But Williams' vivid characters were not the product of pure imagination — his difficult childhood and personal life were the key to his success as an author, and he drew heavily from a deep well of personal sadness.

Saddled with an abusive alcoholic father, a puritanical mother, and a mentally ill sister, Williams was surrounded by a gamut of dark figures from his earliest years. Although Williams did see serious commercial success and critical acclaim after he produced "The Glass Menagerie" in 1944, stardom was never enough to vanquish his inner demons.

Williams' childhood had given him a nervous and melancholy personality, and during his later years, his depression and drug addiction got wildly out of control. Nor did his success last forever. Sadly, in his later years, the failure of his newest plays contributed to his terrible downward spiral into oblivion.

The following article includes references to alcohol and drug misuse, physical abuse, sexual assault, and hate crimes.

William's father was an abusive alcoholic

Tennessee Williams didn't get the best start in life; the often discontented characters in his work are pulled directly from his personal life. When he was a small boy, his father Cornelius Williams worked as a traveling salesman, and he was a very poor parent and husband when he was at home. Cornelius was addicted to alcohol and would disturb the family home with his drunken rages, starting fights with Williams' mother. A consummate womanizer to boot, he once came home with a case of gonorrhea given to him by a prostitute and he spent a great deal of the family's money on poker games, plunging them into penury (via Donald Spoto's "The Kindness of Strangers").

According to John Lahr's "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh," William's frequently admitted to being afraid of his father, who showed him nothing but coldness for most of his childhood. As an adult, Williams also spoke contemptuously of his dad, remarking that his father "does nothing but stay home and drink," and "when sufficiently drunk I think he is dangerous." Unsurprisingly, bad husbands and absent fathers became a feature of William's work, most notably in the heavily autobiographical work "The Glass Menagerie," — the father in which is a drunk and abusive traveling salesman.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

Williams was frail and sickly as a child

While today we might be thankful that Tennessee Williams became a bookish child, his love of literature was partially the result of a terrible illness. As a child, Williams was frequently ill and eventually caught diphtheria, a debilitating disease that made him painfully frail.

Confined to his bed, Williams lost the use of his legs for several years. Later in life, he believed his early brush with illness had severely affected his development, stating "... I was so weak that I had to push myself along the floor. I couldn't walk. Naturally, I became, and from that time on remained, a neurotic and introverted child. I remember developing my first true neurosis at the age of 10. I was terrified to go to sleep at night because sleep seemed to me so similar to death" (per "Conversations with Tennessee Williams").

While this development made Williams turn to the typewriter to amuse himself, it also earned him the disgust of his characteristically cruel father. Rather than supporting his sickly child, he frequently referred to the young boy as "Miss Nancy" for his disinterest in sports. At school, he fared little better, and children routinely picked on him for being too sickly (via Donald Spoto's "The Kindness of Strangers").

His mentally-ill sister Rose was lobotomized

Tennessee Willams' family life was generally pretty dark but it reached its terrible nadir when his sister Rose Williams was lobotomized after a severe breakdown. She, like Williams, struggled to cope with their father's rage and his drinking, growing increasingly fragile and nervous. As a young woman, she became hysterical when her beloved mother was sick and began to insist that her food had been poisoned and that the family was in danger (via Donald Spoto's "The Kindness of Strangers"). Her behavior became increasingly strange as she got older, which led to regular hospital visits and eventually a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Rose's outbursts, especially those which were sexual in nature grew to be quite frightening and led her doctors to undertake the terrible surgery that would render her disabled for the rest of her life. Shortly before she was lobotomized she threatened to kill her father and began to claim that he had raped her— a claim it was impossible to establish the veracity of in her confused state.

Following the surgery, Williams allegedly felt a great deal of guilt about his sister, who is believed to have been the model for the delicate Laura in "The Glass Menagerie," and the disturbed Blanche Dubois in "A Streetcar Named Desire." Williams had sometimes been cruel to his sister but he had also failed to prevent the terrible surgery he did not approve of. Later in life when success brought money, Williams used his royalties to pay for Rose's care and spoiled her with gifts as often as he could.

He had a nervous breakdown aged 24

In his early 20s, Tennessee Williams' future looked fairly bleak. Trapped at home with his dysfunctional family, pulled out of university by his father, and stuck working a terrible job at the local shoe factory, Williams' life was a miserable one. According to John Lahr's "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh," Williams described working at the shoe plant in the blackest of terms, calling it a place "designed for insanity ... a living death." At the same time, he dreamed of being a writer, a profession his father scoffed at. In the weeks leading up to his breakdown, Williams began to make more and more mistakes at work, culminating in the screw-up of a $50,000 delivery (via Donald Spoto's "The Kindness of Strangers").

In addition to his work struggles, Williams had also begun to question his sexuality and his chaotic and unhealthy home life at home with his parents took its toll on his nerves. Reaching the end of his tether in 1935, two days before his birthday he had a nervous breakdown on the way home from the movies. Williams was struck down by a panic attack in a service car and was finally sent to the hospital. The doctors noted he was experiencing a great deal of emotional turmoil, and he decided to move in with his grandparents for a time to recover.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Williams struggled with his sexuality and experienced homophobia

Tennessee Williams grew up during a time when homosexuality was still illegal, not to mention completely taboo. Early in life, he also had some discomfort with sex in general — John Lahr writes in his biography, "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh," that his puritanical mother hated sex and screamed the house down every time his father made advances on her. Williams vomited after his first heterosexual experience and after one of his earliest homosexual experiences as well. Unable to shake his feelings of disgust, he wrote in his diary, "Rather horrible night with a picked up acquaintance Doug whose amorous advances made me sick at the stomach ... Purity! — Oh God — it is dangerous to have ideals."

Although later in life Williams was very open and frank about sex, coming out as a gay man was still difficult at that time — before he publicly admitted it, several journalists tried to out him in public. As news spread that he was a homosexual, he recounted to "Playboy" magazine: "I became socially ostracized in Key West. People drove past my house screaming, "F*****!" (per "Conversations with Tennessee Williams"). On other occasions, his hateful neighbors would throw rubbish into his yard, throw eggs, or even urinate on his plants.

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

The love of his life died tragically young

Tennessee Williams had many lovers throughout his life but his love affair with his assistant, and a jobbing actor named Frank Merlo was one of his longest-lasting and most impactful relationships. The two stayed together for around 15 years, and William's play, "The Rose Tattoo" was inspired by the handsome Sicilian.

Grounded, sensible, and intelligent Merlo kept the often deeply troubled Williams on an even keel for many years (via John Lahr's "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh"). Nonetheless, the pair were eventually driven apart by Williams' wild nature, his promiscuous behavior, and his drink and drug binges. Unfortunately, just after the pair had become estranged in a difficult breakup, Merlo was suddenly taken extremely ill with inoperable lung cancer. After finding out through the grapevine that Merlo was sick, Williams' rushed to his bedside in time to be with him in the months before he died — Merlo had been given just six months to live and died aged 41.

According to "Conversations with Tennessee Williams," Williams' friends believed that it was Merlo's death that most severely worsened his terrible slide into drug addiction. Williams himself remarked, "Immediately after the death of Frank Merlo, I was paralyzed, unable to write, and it wasn't until I began taking the speed shots that I came out of it."

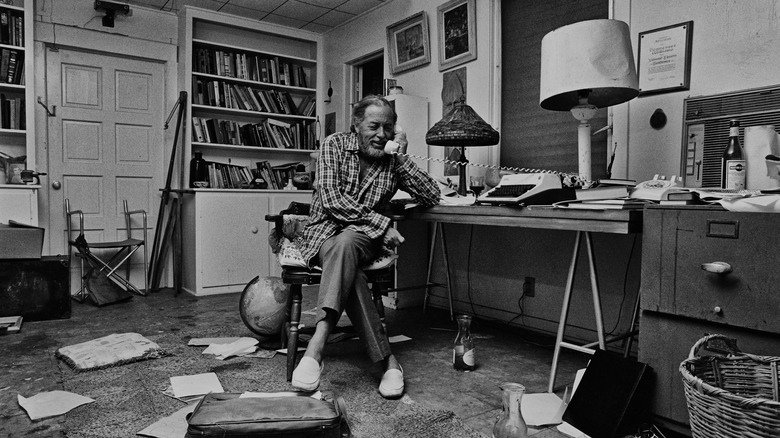

In the late '60s and '70s he produced a string of commercial and critical failures

Tennessee Williams had his heyday in the 1940s and '50s with a string of commercial and critical successes, including "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" and "A Streetcar Named Desire." During the '60s and '70s however, his work began to flag and he dealt with a great deal of bad press. Following the death of his ex-lover and longtime friend Frank Merlo, the '60s became a drug-fuelled haze for Williams, and critics panned his new writing. In 1969 for example, a review of his "In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel" in "Life" magazine stated that Williams was "finished" as an artist and Williams was devastated (via "Conversations with Tennessee Williams").

Unfortunately, the struggling playwright was a sensitive person who was badly wounded by negative critical reactions. In letters to friends, Williams wrote about his self-loathing and terrible lack of confidence. He once remarked, "There have been times when I have been truly crushed, humiliated, over the unkind remarks of critics. Some playwrights say they pay no attention to reviews, but I guess I'm not that strong because the bad ones hurt me. Really hurt."

He descended into depression

Throughout the course of his troubled life, Tennessee Williams had many dark periods of deep depression. The worst of these occurred during a period of artistic frustration and terrible grief in the 1960s. Williams claims he sunk into a lengthy depression that started in 1963 and lasted all the way up to his complete breakdown in 1969 (via "Conversations with Tennessee Williams").

According to Donald Spoto's "The Kindness of Strangers" Williams like many depressives, shunned his friends during this period and indulged heavily in drugs. By 1967, Williams' already fragile state of mind was shattered further by illness and the death of his close friend fellow, author Carson McCullers. That December a friend recalled that on a trip to London Williams arrived at his hotel muttering "I want to die. I want to die..." over and over again.

This particular depressive spell finally culminated in a massive panic attack — in his drug-addled state he became convinced that he was going to die after spilling hot coffee himself. The result was a major intervention, during which he was hospitalized in the psychiatric division of a local hospital and taken off his heady cocktail of drugs. Sadly, it would not be his last period of mental illness, and by 1976, Williams had sunk into depression once again.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

He misused drugs

To cope with his black moods, Tennessee Williams started taking a lethal cocktail of drugs and mixed them with alcohol. To the horror of his friends, the drugs made Williams unpredictable, paranoid, and prone to outbursts.

In addition to taking barbituates and other pills, William's celebrity doctor, nick-named "Dr. Feelgood," began giving him injections of speed. At the height of his depression, Williams felt he needed the drugs to keep him working but they often backfired. In an interview with "Playboy" magazine, William's joked about his awful daily routine, saying "I began washing the pills down with liquor and I just went out of my mind. I took sedation every night, and every morning I took something related to speed, so that I could still write" (per "Conversations with Tennessee Williams").

Donald Spoto writes in "The Kindness of Strangers" that Williams was taking such a potent cocktail of drugs that an intervention on his behalf went horribly wrong. Forced to go cold turkey, Williams had three seizures and two heart attacks during his withdrawal period. The intervention also didn't work — following his treatment Williams simply went back to experimenting with more drugs. Instead of injecting speed, he started taking Ritalin and barbituates instead.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Williams was repeatedly attacked for immorality throughout his life

While today he is universally celebrated for his brilliance, Tennesse Williams was not without his detractors while he was alive. Williams was keen to showcase some dark subject matter, much of which was sexual in nature. As a result, he seriously annoyed some pious theatre-goers who found him shocking. One of William's earliest works, "Battle of the Angels" so annoyed his puritanical critics that the Boston Police commissioner and the city censor demanded that he rewrite it (via John Lahr's "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh"). Critics generally regarded it as a "dirty" play with too many innuendos hidden in the dialogue. In the U.K. on the other hand, The Guardian reports that "A Streetcar Named Desire" was seen as so shocking to its 1949 audience, Williams' work was attacked in Parliament.

The press was frequently upset by veiled references to homosexuality in his work as well as the tackling of sexual subjects. The rape that is central to the story of "A Streetcar Named Desire" for example, became a particularly thorny issue. When the play was being made into a film, the PCA tried its hardest to censor the script and remove the rape entirely. Similarly, the subject matter of his work "Baby Doll" was condemned by the Catholic Church when it was transformed into a movie. The New Republic called the film, "Just possibly the dirtiest American-made motion picture that has ever been legally exhibited," a criticism that modern audiences may find laughable.

He accidentally died from taking barbiturates

By the time Tennessee Williams was an old man, he still had not kicked his drug habit, and it would ultimately be the end of him. In 1983, Williams was found dead in his hotel room and the scene made for grim viewing; according to John Lahr's "Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh," first responders found 13 bottles of prescription drugs in the room.

To begin with, it was officially reported in the press that Williams had died choking on a bottle cap — however, the actual cause of his death remained uncertain. Although Williams had indeed swallowed the cap, it was lodged in his mouth not his throat, and had not actually obscured his airways at all.

On the other hand, the autopsy indicated he had a potentially lethal level of barbituates in his system — and he appears to have been using the cap to administer a dose when he accidentally swallowed it. The Independent reported that either way, his overuse of drink and drugs appears to have caused his gag reflex to fail when he swallowed the plastic cap. Williams was aged 71.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).