'Trials Of The Century' You Probably Forgot About

"Every time I turn around, there's a new trial of the century," famous defense attorney F. Lee Bailey once declared to The Washington Post. While this is certainly hyperbole, it is true that each century since the 19th has had more than its fair share of cases dubbed "the trial of the century." These cases were media frenzies, and the resulting trials were national obsessions.

Trials, particularly those featuring pseudo-celebrities and wealthy socialites, have fascinated people since before Lizzie Borden was accused of taking an axe and giving her mother forty whacks, but not all of these cases have remained as prominent in the public consciousness as the Borden murders. Some of the trials that captivated the public have been largely forgotten, but even today, decades after the crimes were committed and all those involved have died, they are fascinating stories. They can also provide a unique insight into what shocked, horrified, and fascinated people of the past — so, here are some "trials of the century" you probably forgot about.

The following article includes descriptions of racism and hate crimes.

Leopold and Loeb

Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold were both well-educated, wealthy, teens living in Chicago in the early 1920s. Loeb was charming and had good prospects, despite his penchant for petty vandalism and arson. Leopold published scientific papers while studying at law school. The two were an unlikely pair, but they had an intense romantic relationship. When Loeb confessed that his deepest desire was to commit a violent crime that would captivate the city of Chicago, Leopold agreed.

In 1923, they tricked a child named Bobby Franks into their car and crushed his skull with a chisel. After dumping the body, they believed they had committed the perfect crime — but Leopold's glasses fell out of his pocket. The resulting trial became a media frenzy. The details of the murder were used as a cudgel by those opposed to the cultural shift the country was going through, and traditionalists attempted to link the prevalence of education with child murder. The public wanted Leopold and Loeb executed, but their attorney, Clarence Darrow, would make sure that never happened.

In 1925, Darrow would become one of the most famous lawyers in history when he defended John Scopes in the Scopes Monkey trial. His defense of Leopold and Loeb also hinged on evolution. He argued that "man is an animal" and that criminal behavior was a medical issue that should be treated, not punished. Darrow had psychiatrists explain the possible causes of both teens' behavior. While both went to prison, neither was executed.

The murder of Stanford White

New York City was undergoing a major shift in the early 20th century, both culturally and physically. As noted by New York architecture expert Brendan Gill for PBS, both of these changes were heralded by Stanford White. At his architecture firm, McKim, Mead and White, White changed the New York City skyline. His murder would change the media.

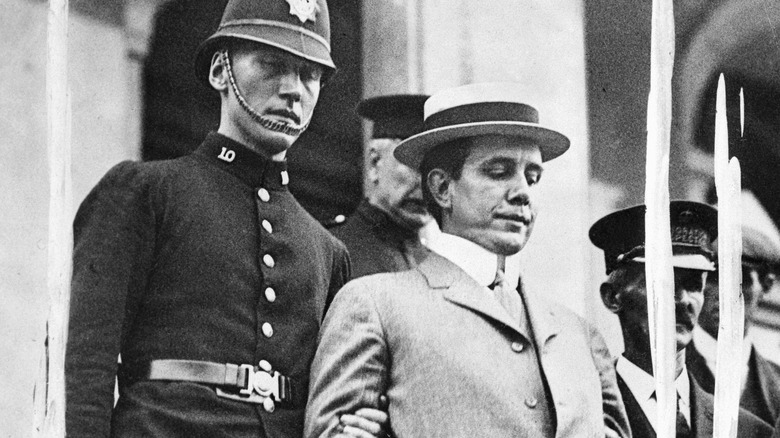

The trial became an object of morbid curiosity, and the scandalous details of the crime were used as an example of the decadence and immorality of the elite. White was killed by another pinnacle of New York society named Harry Thaw, who had a reputation for bizarre cruelty and violence. Thaw was married to a young woman named Evelyn Nesbit, who had achieved fame and fortune with her good looks and charm. She and White had an affair both before and after she married Thaw. In a fit of jealousy, the unstable Thaw shot White. During the trial, he would claim he had been avenging his wife after White assaulted her.

The impact on New York was immediate. For the first time in history, a surge of tabloids appeared to cover the trial and publicize the details of the crime. There was no doubt that Thaw had shot White, but he was found not guilty on the grounds that he was "a dangerous lunatic." According to a report from The World, Evelyn Nesbit was thrilled that her husband would be sent to an asylum.

Chicago's Belva Gaertner

The musical "Chicago" is set in the 1920s and follows the stories of two showgirls on trial for murder. While the play is fictional, it was inspired by several actual trials that took place in Chicago in the 1920s, and was written by the woman who helped to make those trials a national obsession. The first of these was the murder of Walter Law, who was found shot dead in the car of cabaret performer Belva Gaertner. While Law had been killed by Gaertner's gun in Gaertner's car, she claimed that she had been too drunk to remember if she had killed him.

As described by Marianne Constable's 2006 article in Triquarterly, there had been an unusually high number of cases of women committing murders around this time — and very few of them were convicted. One of these cases was defended by famous attorney Clarence Darrow, but even without his assistance, dozens of women got away with murder. The future playwright of "Chicago," Maurine Watkins, was working as a reporter at that time, and saw an opportunity in the Gaertner case. The cabaret star was charming and irreverent, full of witty quips like, "Gun and guns — either one is bad enough, but together they get you in a dickens of a mess."

Reporting on Gaertner's trial and acquittal, and the trials of several subsequent accused murderesses, made Watkins' career, the trials a subject of public fascination, and the accused into household names.

The Haywood Trial

In December of 1905, the former governor of Idaho, Frank Steunenberg, opened his front gate and inadvertently set off a trap that had been set just for him. A bomb went off, killing Steunenberg and setting in motion the most widely publicized legal battle Idaho had ever seen. As described in Joseph R. Conlin's 1968 article for The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, it is also among the most important court cases in the history of American labor.

The first suspect was a man going by the name Harry Orchard, who actually confessed to the crime. The confession was kept a secret, however. Orchard had at one time been a member of the Western Federation of Miners, and the prosecution had its eye on a bigger name for the crime: powerful union leader William D. Haywood.

Haywood was defended by the famous attorney Clarence Darrow, who would be a participant in multiple "trials of the century" throughout his career. The trial lasted two months, and was widely publicized across the nation, bringing to light the horrendous conditions endured by American miners. Ultimately, Haywood walked free. Orchard spent life in prison.

Leo Frank Trial

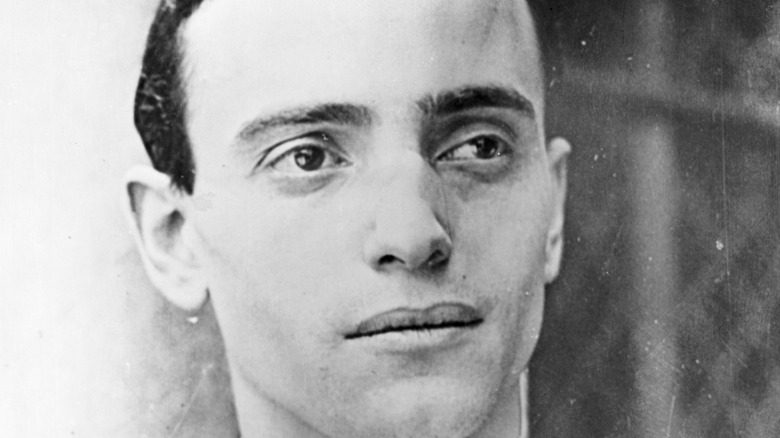

In 1913, a 13-year-old factory worker named Mary Phagan was murdered. She went to collect her paycheck from the factory superintendent, a young Jewish man named Leo Frank. As described by Sandra Berman of the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum (via PBS), Frank was the last person to admit to seeing Phagan that day, and was blamed for her murder. The trial lasted for three weeks, and Frank was at first convicted and sentenced to death. The appeals took Frank's case to the Supreme Court.

Modern scholars, including Steve Oney, who wrote a book about the Frank case (via Atlanta Magazine), believe that Leo Frank was innocent. The killer was probably a cleaner who also worked at the factory and was present on the day of the murder: Jim Conley. Conley had been seen washing blood out of his shirt shortly after the time of the murder. Conley would become the primary witness against Frank, claiming that Frank had been the killer and he had only helped to hide the body.

The trial was covered extensively in the press. While the Supreme Court determined that Frank was not guilty, the American public, riled up by the media coverage and a powerful undercurrent of antisemitism, disagreed. In 1915, a mob of men who came from Phagan's hometown drove to the prison where Frank was still being held, abducted him, and murdered him.

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

Anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti

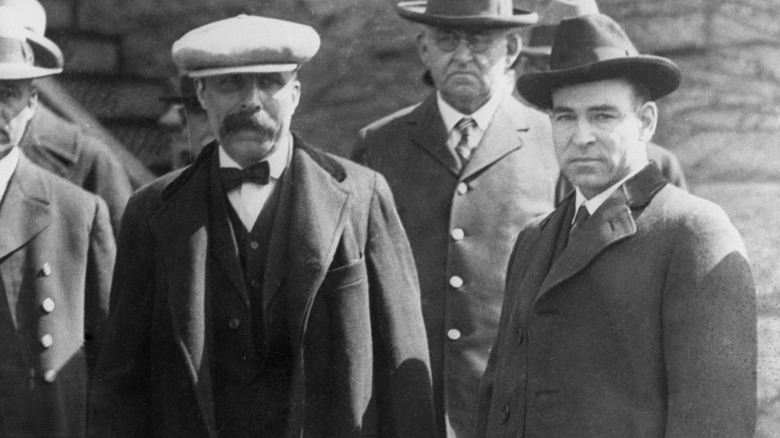

On April 15th, 1920, the modern-day equivalent of more than $200,000 was stolen from a Massachusetts shoe factory. During the robbery, both a payroll clerk and a security guard were killed. Who actually committed these crimes is still debated, but a few weeks later, two men were arrested: Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The first "Red Scare" was in full swing, and both men were anarchists. There was never any evidence that Sacco and Vanzetti had done anything other than having radical beliefs, being Italian immigrants, and not registering for the draft, but that didn't stop them from being convicted and executed.

Regardless of what really happened at the shoe factory on April 15th, experts agree that the two did not receive a fair trial. As described by future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter in 1927 (via The Atlantic), some members of the jury had been hand-selected by the Sheriff's department because they were members of the Masons. The accused were seen as outsiders, and treated with extreme suspicion. Many of the witnesses who identified them testified to things that they could not have seen from their positions, or later admitted that they couldn't confidently say whether the men they saw were Sacco and Vanzetti. In 1927, both men were executed.

Hall-Mills murder case

In September of 1922, the bodies of two people were discovered with love letters strewn across their corpses. One was Edward Wheeler Hall, a handsome Episcopal minister who was married to a wealthy heiress. The woman beside him was not his wife — she was Eleanor Mills, a member of the church choir.

From the beginning, the case fascinated the public. The crime scene itself was partially destroyed by onlookers trying to see the bodies. Hall's wife and her brothers were accused of the murders, leading to one of the most widely followed trials in American history. The trial included bizarre characters like the "Pig Woman" — because she raised hogs for a living — who testified from a bed while her own mother called her a liar in the audience. The erotic love letters of the victims were read aloud. Mrs. Hall and her brothers were ultimately acquitted, and the truth of what happened is still unknown.

Some, including journalist and author Joe Pompeo for The New Yorker, have linked this case to the beginning of America's true crime obsession. Hundreds of journalists traveled to New Jersey for the trial, absolutely taking over the town of New Brunswick in their desperation to be the first to tell the story to their readers.

Victoria Vanderbilt custody hearing

While most of the cases that have been called "The Trial of the Century" are murder cases, one of the most well-publicized and infamous trials in American history was actually a custody hearing. The child in question was Gloria Vanderbilt, who at only 10 years old was due to inherit a fortune. Her mother, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, and her aunt both believed that they should be her guardian. It was the height of the Great Depression, and for the American people, it was a look into the messy lives of the extremely wealthy — and they couldn't look away.

In 1934, young Gloria Vanderbilt's mother attempted to have herself legally declared her child's guardian, but her late husband's sister, Gertrude Whitney, claimed that she was an unfit parent. The news shocked and fascinated the destitute American people.

One of Morgan Vanderbilt's maids claimed that she had sexual relationships with women. The court was shown letters, reportedly from young Gloria, that she wanted to live with her mother, but the judge stated that Gloria had told him that she hated her mother. Later, she would state that she had been coached to say this by her aunt's lawyers. Ultimately, her aunt was granted custody, and her mother was only permitted to visit on weekends.

The Scottsboro Affair

The Scottsboro boys are not as widely known today as some other cases of false accusations against Black Americans, such as the events leading up to the Tulsa Race Massacre, the Central Park Five, and the murder of Emmett Till, but it led to international outrage that helped spark the civil rights movement. It also inspired Harper Lee to write "To Kill a Mockingbird."

On March 25th, 1931, some unemployed young men were taking a train through Alabama to find work. Nine of them were Black boys, between the ages of 12 and 19. During the trip, it is believed that a young white man stepped on one of the teenager's hands, and a fight broke out, and the white men were forced to leave the train. In an apparent act of retribution, they reported that the teenagers on the train had raped two white women passengers.

They were arrested, and in the initial trial, eight of the nine boys were sentenced to death. After public outcry and public protesting, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions. What followed was a series of retrials that led to national debate about bias in the court system, and a landmark decision by the Supreme Court that Black Americans could not legally be kept off of juries. Ultimately, five of the nine boys had their convictions overturned, one was pardoned in 1976, and in 2013, the remaining three were posthumously pardoned.

Wayne Thomas Lonergan trial

In 1943, the brutal murder of the young, fashionable, and wealthy Patricia Lonergan became a sensation. As described by journalist Dominick Dunne for Vanity Fair, the public was as obsessed with her life as they were with her death, and during the trial, sensational and shocking facts about her marriage became a topic of national discussion. Her husband, Wayne Thomas Lonergan, was described as an attractive bisexual Canadian fortune hunter who had once had an affair with his wife's father.

Onlookers were desperate to catch a glimpse of Lonergan as he made his way from jail to court each day. His good looks and fluid sexuality, paired with the likelihood that he had murdered his wife, made him a fascinating figure for the crowds who waited outside the courthouse and for tabloid readers around the world.

At first, he claimed he had been in the arms of a nonexistent soldier on the night of the murder, but ultimately confessed that he had killed Patricia Lonergan. He spent three decades in prison, before being paroled and sent back to Canada.

The Scarsdale Diet doctor

The Complete Scarsdale Medical Diet was an extreme crash diet plan released in 1978. Its creator, Dr. Herman Tarnower, claimed it could help adherents to lose 20 pounds in two weeks. In 1980, Tarnower was murdered by his partner, a private-school headmistress named Jean Harris. As described in Mark J. Phillips and Aryn Z. Philips's 2016 book "Trials of the Century," what followed was one of the most sensational trials in American history. The coverage of the case, which centered on a love trial between Tarnower, Harris, and a younger woman, was scandalous enough to capture public attention, but it also tapped into the cultural moment and became linked to the rise of Second Wave Feminism. Some viewed Harris not as a murderer, but as the victim of the patriarchy.

There was no doubt that Harris had shot Tarnower — the question was why. Initially, the prosecution believed that Harris had come to Tarnower's home planning to kill him, but during the course of the trial, they came to believe that she had actually planned for Tarnower to kill her. Harris claimed that she had intended to kill herself, not Tarnower, but accidentally shot him instead.

Harris was convicted of second-degree murder and sent to prison. As noted by The New York Times, she spent her time in prison educating her fellow prisoners. After her release in 1993, she committed her life to a charity that helped the children of incarcerated women to get an education.

The murder of Marilyn Sheppard

In the summer of 1954, Marilyn Sheppard was murdered, beaten to death in her bed. Dr. Sam Sheppard, half-dressed and obviously injured, told investigators that he had been awakened by screams, seen a person with bushy white hair standing over her, and been knocked out in a fight. Upon recovering, he found his wife dead.

The response from the press was immediate, and all reporting on the murder seemed convinced that Sheppard had committed the murder. It was so widely reported on in Ohio that it was a struggle to find jurors who had not already heard about the case, and there remains debate over whether or not the eventual jury was biased. The judge had already decided for himself that Sheppard was guilty, and spoke about that belief openly.

The trial was nine weeks long, and remained in the headlines throughout. Sheppard was convicted, and it would eventually be ruled "a mockery of justice," as noted by The National Registry of Exonerations. In 1966, after more than 10 years in prison, Sheppard had a retrial and was declared not guilty. The murder of Marilyn Sheppard remains unsolved.