Native American Historical Figures They Didn't Teach You About In School

It's unfortunate, but Native American figures are grossly underrepresented in too many American history classes. For many students, their only instruction regarding Indigenous people is limited to just a few figures, like Squanto or Crazy Horse, and most others are completely omitted. Even worse, some people's only familiarity with them is linked to Disney movies or Hollywood motion pictures. Yet, Native Americans have always played a very important role in American history, even if it is not always acknowledged as such.

As the original inhabitants of the lands now known as the Americas, Indigenous history is just as important as United States history — or any other history for that matter. Besides the big names like Sacagawea or Pocahontas, there were thousands of less-recognized Native Americans who made contributions that were just as vital. They have a very rich and extensive history, which deserves much more attention than it is regularly given.

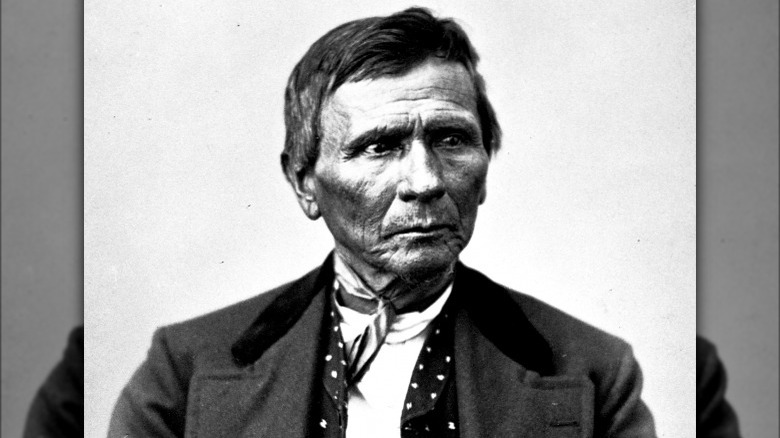

Smohalla

Smohalla was a Wanapum American Indian who was born in the early part of the 19th century. He lived in what is now Wallula, Washington, and was originally named Wak-wei, which meant "arising from the dust of the Earth Mother," as per HistoryLink.org. Even from a young age, he was believed to have had incredible spiritual powers, and he later had his name changed from Wak-wei to Waipshwa for "rock carrier," and eventually to Smohalla, which meant "dreamer."

According to contemporary sources, Smohalla had a group of followers, called "Dreamers," and he was able to predict future events that were going to happen. This included everything from natural events like eclipses and earthquakes, to even where the best hunting, fishing, and food gathering was. Smohalla lived at a time when Native Americans were forcefully losing their land to the United States. He rejected acquiescing to the proclivities of white farmers encroaching on their territory and advocated to his fellow natives that they were better off without them.

He also preached that if the still surviving natives rejected the intrusions and remained with their traditional ways, the Great Spirit would resurrect their dead comrades and bring them back to life to fight alongside them. His beliefs brought him into conflict with both the U.S. government and other Indigenous people. He was eventually exiled from the Wanapum and died on the Yakama Reservation in the 1890s.

Mangas Coloradas

For many years, Mangas Coloradas was one of the most important Mimbreño Apache figures living in what is now considered the New Mexico area. Born in the late 18th century, Coloradas was known for his large physical stature, and his name meant "Red Sleeves," as per HistoryNet, but it's not entirely clear the significance. During Coloradas' time as the Mimbreño Apache chief, officials from the U.S. started encroaching on Apache territory.

At first, Coloradas was welcoming to the new settlers, and he may have viewed them as possible comrades in his battles against other tribes and Mexican nationals in the area. However, things quickly broke down when soldiers from the U.S. Army began attacking Apache tribesmen, partly due to their ignorance about the dynamics of tribal life. In response, Coloradas and the Apaches fought various elements of the U.S. Army in what is now known as the Apache Wars.

Coloradas was the father-in-law of the famous Chiricahua Apache Chief Cochise, and together their tribes fought the U.S. Army. During the Battle of Apache Pass, they assembled a war party and raided Fort Bowie, but this resulted in severe wounds to Coloradas. About six months later, Coloradas met with various U.S. officials near Fort McLane to discuss peace, but the officials brutally tortured and murdered him, before beheading Coloradas in the name of science. Coloradas' death led to retribution from the Apaches, which only continued the downward spiral of violence.

Hiawatha

While many people are undoubtedly familiar with the Iroquois Confederacy that used to reign in New York, the history of the founder of the confederacy, Hiawatha, is not talked about nearly as often. Hiawatha was likely born in the early-16th century and spent his formative years with the Onondaga and Mohawk tribes, though much of his life is shrouded in mystery. What is known is that Hiawatha, along with Deganawida the "Great Peacemaker," were instrumental in the creation of the confederacy, which lasted for around 200 years.

Following a great personal tragedy involving the loss of his daughters, Hiawatha became a follower of the Great Peacemaker. Hiawatha helped the Great Peacemaker to spread his message of unity to other tribes in the area, and his strong oratory and cultural skills are said to have helped him immensely. First, Hiawatha and the Great Peacemaker convinced the Mohawk tribe to join with Onondaga, of whom Hiawatha was now chief. Then, they convinced the other three tribes in the area — the Senecas, Cayugas, and Oneidas — to join together to create the five nations.

Later, the Tuscarora would join in 1722, and the confederacy lasted until the late-18th century when the influx of white settlers forced the natives from their lands. Hiawatha never lived to see the dissolution of the confederacy, which would last until the Treaty of Ft. Stanwix in 1784.

Opechancanough

Opechancanough, born in the mid-16th century, was once a very powerful chief of the Tsenacomoco tribe. He may have also been known as Don Luís de Velasco, but that is debated among historians. As chief of the Tsenacomoco, Opechancanough was responsible for protecting the Pamunkey River approach from enemies, and he was related to the famous Chief Powhatan, the paramount chief of the Tsenacomoco.

Opechancanough was responsible for the capture of Captain John Smith — later of Pocahontas fame — but treated him well and introduced him to Powhatan. Later, Opechancanough helped lead the Tsenacomoco tribe during the Second and Third Anglo-Powhatan War against the English, which only came to a close with Opechancanough's capture and subsequent murder in the 1640s.

By that time, Opechancanough had already become the paramount chief of the Tsenacomoco. To fight the English, Opechancanough would use tactics to make the English think he was friendly to them, before launching a surprise attack that would result in the deaths of 100s of colonists. Much of what is known about him today is from the works of English authors, where he is often portrayed as a murderous villain. The truth about Opechancanough is much more complex and reveals a troubled man struggling with the loss of his land to English settlers.

Dragging Canoe

The story of Dragging Canoe is one of the most important in Native American history. Dragging Canoe lived in the late-18th century during the breakout of the Revolutionary War. He earned the name Dragging Canoe due to his dedication to being a skilled fighter, and by the time of the American Revolution, he was one of the top Cherokee warriors. When the war first broke out, Dragging Canoe and his allies rejected a peace settlement with the colonists, instead deciding to attack them.

Striking the colonists in multiple places at once, the Cherokee were not powerful enough to drive them away, leading to a bloody defeat. As a result, Dragging Canoe and others established the Chickamauga offshoot of the Cherokee and continued to bring the fight to the colonists. The Chickamauga Cherokee under Dragging Canoe fought the (now) Americans several more times and were able to defeat them and repel their attacks.

In his time the Chickamauga were successful at resisting the encroach of the Americans, and Dragging Canoe did not die until after the revolution had ended, in March 1792, with much of his Indigenous lands still under native control.

Black Beaver

Black Beaver was born in 1806 into the Delaware Tribe, in what is now Belleview, Illinois. By 1834, Black Beaver was already working as a guide and interpreter for various officers in the U.S. Army. In the 1840s, he formed "Black Beaver's Spy Company, Indian, Texas Mounted Volunteers," and they fought on the Americans' side during the Mexican-American War. After the war, he continued to work as a scout, guide, and interpreter, eventually retiring near Fort Arbuckle just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War.

When the Civil War did break out, Black Beaver stayed loyal to the Union instead of defecting to the Confederacy. He helped Union officers to capture enemy prisoners of war, and he also led a huge column of Union forces through miles of treacherous Confederate territory from Fort Cobb to Fort Leavenworth. Throughout the war, Black Beaver continued to contribute to the Union cause, and he faced reprisals from the Confederates when they destroyed his livelihood near Arbuckle.

Later in life, Black Beaver would become a Christian and a Baptist minister, and he died in 1880. In the 1950s, he posthumously became the inaugural entrant into the American Indian Hall of Fame.

Santa Anna

For many Americans, the name Santa Anna is synonymous with the Texas Revolution and the Battle of the Alamo, and not many realize there was an important Penateka Comanche chief who also went by the same name. Santa Anna, the Native American, was likely born near the turn of the 19th century, and coincidentally happens to have lived in present-day Texas. Like many natives of his time, Santa Anna originally feared the encroachment of U.S. settlers onto Comanche territory.

He participated in several battles to try and stop them, such as Plum Creek and possibly the 1840 Linville Raid. But in 1846 he agreed to a peace treaty with the U.S. However, Santa Anna was not mollified in his fight against the intrusion of American settlers onto his land — that is until he reportedly traveled to the capitol at Washington, D.C. Something about D.C. changed Santa Anna, and when he returned he changed from advocating for armed resistance to accommodation for the settlers.

This did not make Santa Anna very popular among his fellow Comanches, and he may have tried to rehabilitate his image by leading attacks in Mexico. Santa Anna died in 1849 from a cholera epidemic, leaving his tribe to splinter apart.

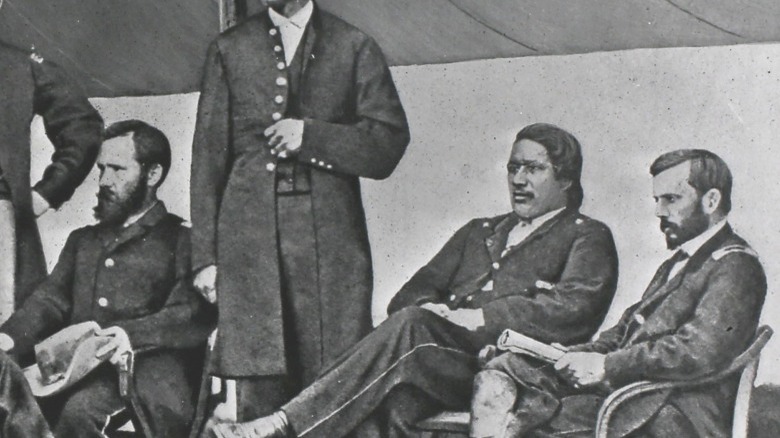

Ely Parker

Considering his role in helping the Union Army during the Civil War, it's surprising that Ely Parker's name is not mentioned more often when schools teach about American history. Parker was born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Reservation in New York. He later attended the prestigious Cayuga Academy school where he experienced tribulations but still got a good education. After a few years, he was educated enough to be able to help the Tonawanda Seneca in their negotiations with the U.S. government.

He later attempted to be a lawyer but was denied due to legalized discrimination owing to his Native American heritage. While not an official lawyer, Parker still helped to argue Native American cases before the Supreme Court, and he was successful a number of times. Parker also became an engineer as well as a leader of the Iroquois Confederacy.

During the Civil War, his friend Ulysses S. Grant made him an engineer in the Union Army of Tennessee, and later he became Grant's military secretary. He helped to write the terms of surrender that ended the Civil War and served as the Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs under Grant during his presidency. Parker almost lived to see the turn of the century, passing away in 1895 of natural causes. He worked both for Wall Street and the New York City Police Department before his death and died with full military honors.

Pushmataha

Though he was one of the most significant Choctaw leaders in modern Native American history, many people still do not know the name of Apushamatahahubi, or Pushmataha for short. He was born in the mid-18th century in what is now Mississippi as a member of the Choctaw tribe who were constantly fighting with the rival Creek tribe. Pushmataha quickly became an important and fierce warrior in his tribe, and in 1800 had risen to the position of Choctaw chief.

At a time when the U.S. was expanding and slowly ripping away Indigenous lands, Pushmataha negotiated with U.S. officials as a Choctaw representative after becoming chief. He actually fought on the side of future president and then Gen. Andrew Jackson during the Creek War of 1813-1814, but found that his support did not mean the government would be any more conciliatory towards him and his tribe.

Forced to continually cede land, in 1820 Pushmataha tried to get his old friend Jackson to come to better terms but was forced to sign a lopsided treaty. While attempting to renegotiate with Jackson a few years later in 1824, Pushmataha died after becoming sick. In recognition of his help to the U.S. Army, he was given full military honors for his burial.

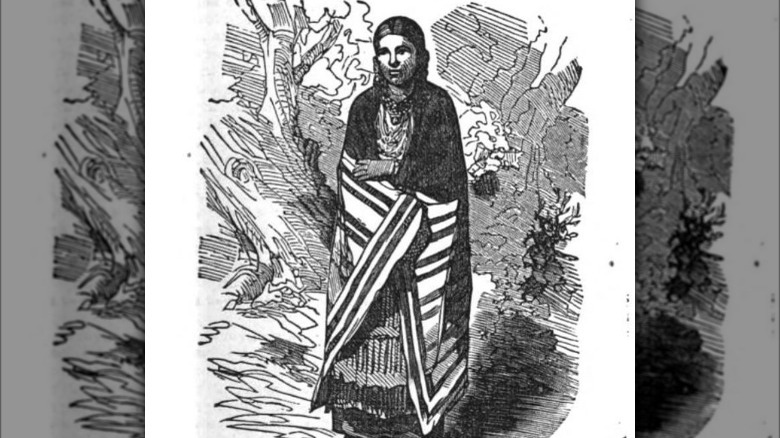

Weetamoo

Weetamoo was a 17th-century chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag tribe and a great warrior. Born in the 1630s, Weetamoo was both a bead worker and dancer in her tribe, and she earned a great deal of respect. During her life, she had several husbands, including Wamsutta, the son of Massasoit, who was famous for his relationship with the pilgrims. As a chief, she came into contact with intrusive English settlers and constantly fought for the rights of her Native American tribesmen to remain on their land.

After Wamsutta's death — possibly from poisoning — Weetamo remarried several times, and soon found herself in the midst of King Philip's War. By the time the war broke out in 1675, Weetamoo was on her fifth and final husband, Quinnapin, and was active in the fight against the English. In 1676, she participated in the Lancaster raid, which resulted in the kidnapping of Mary Rowlandson, who would later write a book about her experiences.

Weetamoo would be killed during the Battle of Mount Hope in August 1676. She was posthumously beheaded, just like King Phillip had been, and her head was put on display as a warning to other warriors.

William Weatherford

An important Creek warrior during the early-19th century, William Weatherford was born near present-day Coosada, Alabama. Around the time he would have been turning 30, Weatherford became embroiled in the Creek civil war that broke out among the Creek confederacy. Weatherford fought on the side of the Red Sticks and took part in the assault on Fort Mims in 1813.

The assault dramatically expanded the scope of the war, and soon Weatherford and the Red Sticks found themselves facing down the barrels of the U.S. infantry. Though they fought bravely, eventually Weatherford and the Red Sticks were forced to surrender. Due to his late cooperation with American forces, as well as due to the high-status position of his family, Weatherford largely escaped retribution for his acts during the war.

Weatherford would end life as a slave owner in 1824, still living in Alabama. During his life, he had many names, including Billy Larney (Yellow Billy) and Hoponika Fulsahi (Truth Maker), and many writers refer to him as Red Eagle due to an 1850s poem. Weatherford is most remembered for the attack on Fort Mims, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds and the forced imprisonment of women, children, and slaves.

Yonaguska

Yonaguska, also known as Drowning Bear, was a Cherokee chief in what is now Tennessee in the 19th century. Living when Americans were snatching up Indigenous territory left and right, Drowning Bear was one of the few who initially advocated for conciliation with the U. S. government. In addition, Drowning Bear was a strong proponent of not using alcohol, which he realized was being used by white Americans as a way to cheaply and effectively (and illegally) negotiate for Native American territory.

Although he advocated for peace with the U.S., by the 1830s Drowning Bear was against giving up any more territory to encroaching Americans. In 1837, Drowning Bear was able to negotiate an agreement that allowed his tribe of Cherokee, the Oconaluftee, to remain in North Carolina while the rest of the Cherokee was removed further west. He then became an ally of the U.S., helping them enforce the removal against his fellow non-Oconaluftee Cherokee.

While at the time his work with the U.S. government may have been condemned, it ended up allowing the Oconaluftee to stay in North Carolina while other tribes had to leave their native lands and push west. He died in 1838 or 1839, likely around the age of 75.

Pi'tamaka

Pi'tamaka, also known as Brown Weasel Woman, was one of the fiercest warriors of the Piikáni Blackfeet tribe. She was interested in hunting from a young age, and she quickly learned the ways of being a Native American warrior under the tutelage of her father. At one point, before he was killed in another battle, she risked her life to save him after he had been severely injured by an enemy war party during a buffalo hunt.

After losing both her parents, Pi'tamaka started living with another Indigenous woman and took over the care of her entire family. She also started joining war parties that were directed at their enemies, mainly the Crow. She became instrumental in helping the Piikáni capture horses from the Crow, which helped her earn the name Running Eagle, a prestigious Piikáni title.

It's unfortunate that Pi'tamaka's name is not more well known to the average high school graduate, because she played an important and influential role for women among the Piikáni Blackfeet. Born in the early 19th century, she died around the 1880s, but it's not entirely clear when.