Weird Things About Joan Of Arc You Didn't Know

Today we remember Joan of Arc mostly from novels and really bad movies starring John Malkovich (as Charles VII, not as Joan). Joan of Arc doesn't get much airtime in non-French textbooks, so most of what Americans know about her boils down to this: She was a rare female military leader, she talked to God, she was burned at the stake, and she looked good in shiny armor.

There really is no doubt, though, that Joan of Arc was a remarkable woman. Mark Twain called her "easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced." She accomplished things no other woman had ever accomplished, and you could even say she made great things possible for all the women leaders who followed her. Still, much of what we know about Joan of Arc is embellished, totally made up, or hardly talked about, so here are some of the more obscure details from the great heroine's short life.

Joan of Arc wasn't from 'Arc' and her name wasn't Joan

We call her "Joan of Arc" today, but that's not what she called herself. For a start, she was French, and "Joan" isn't a French name. Her given name was actually "Jehanne," and she called herself "Jehanne la Pucelle" or "Joan the maid."

So the English translation of "Jehanne" is "Joan," which is why we English speakers don't refer to her as "Jehanne." So that makes sense, but what about "Arc"? Did Joan/Jehanne come from a town called Arc? Nope. According to the St. Joan Center, her father used that name — he was (possibly) from a place called Arc-en-Barrois, hence the surname d'Arc. And since modern people have a really hard time fathoming daughters who don't inherit their fathers' last names, we use "Arc" as Joan's last name, too.

But "Joan of Arc" never used her father's surname. She wasn't born in Arc-en-Barrois but in a village called Domremy, which is where her father married her mother, Isabelle Romee. In France at that time it was the custom for girls to take their mothers' names, so Jehanne/Joan really would have done that if it weren't for the whole wearing armor and getting burned at the stake thing.

She may have suffered from epilepsy or schizophrenia

These days, when someone says "I'm hearing voices," the usual response is "Um ... oh-kay." In Joan's day, hearing voices meant you were either talking to God or to the devil, and either way it wasn't really great news for you. If you talked to the devil you were a witch, which meant you'd get burned at the stake. If you talked to God you were a Very Important Person, which meant that eventually someone would decide you were actually talking to the devil, which meant you'd get burned at the stake.

Joan grew up devout, so when she started to hear voices she truly believed she was talking to God, who'd chosen her for a great and noble purpose. But God may not have been behind those voices — according to LiveScience, at least two modern neurologists have posthumously diagnosed Joan with "idiopathic partial epilepsy with auditory features," a genetic form of epilepsy that affects only one part of the brain and can cause auditory hallucinations. Other historians have speculated that Joan suffered from schizophrenia.

Of course, those theories can never really be proven, unless historians are successful in locating the letters that Joan supposedly sealed with wax and "the imprint of a finger and a hair." If Joan's hair could be found, her DNA could maybe prove or disprove the epilepsy theory. But we probably don't have to tell you how unlikely that is.

Her family wasn't poor

Joan of Arc is often portrayed as a peasant girl who became a great military leader and champion for France, but those stories don't really tell the whole truth. According to author Ronald Gower, there's evidence that Joan's family was not actually poor. After her death, neighbors testified that Joan's father was a "doyden" or senior inhabitant of the village, which means he was next to the mayor in importance. The family were landholders — they had 20 acres, including farmland, meadow, and forest. They also had money stashed away for emergencies, which is a lot more than many modern families can claim to have.

In fact Joan's family doesn't appear to have been suffering at all — their annual income was said to be the equivalent of roughly 200 pounds, which was kind of a lot of money in those days — enough to live comfortably, raise kids, and give a little bit to the actual poor.

So what gives with the "poor peasant" stuff? It might have something to do with the whole underdog thing — it's much nicer to imagine a poor girl becoming the heroine of France than it is to imagine a well-off girl doing the same thing. It's definitely better for public morale, too, especially when the average family in those days tended to be more poor than not.

She was probably more like a figurehead than a soldier

We love to imagine Joan of Arc riding into battle at the head of her army, taking down English soldiers with one arm and praising God with the other. That's probably not exactly how it happened, though, depending on who you ask.

Some of the people who knew Joan of Arc claimed she did all that — charged the British with a lance, fought alongside her men — but not everyone thinks those accounts are accurate. Historian Desmond Seward, who wrote The Hundred Years War: The English in France, said "Joan of Arc merely checked the English advance by reviving Dauphinist morale," and French historian Edouard Perroy basically said she was just a figurehead: "She was content to exhort the combatants, say what advice her voices gave, step into the breach at critical moments and rally the infantry."

On the other hand, it does seem hard to discount all the testimony from soldiers who knew her, though those stories probably were somewhat embellished. Let's face it, if you're going to brag about your close personal relationship with the hero of France, you're probably going to tell people she was way more awesome than she actually was. However, one should never underestimate girl power.

She was a cross-dresser, but not for the reasons you think

One of Joan's most famous quirks had to do with her manner of dress. Today, with a few idiotic holdouts, most people recognize the lame-osity of caring whether a woman chooses to wear a dress, a pair of jeans, or a suit of armor — but during Joan's time it was super, super important. In fact it was so important that it was actually illegal for a woman to dress like a man.

Joan didn't dress the way she did to be more comfortable in battle or because she wanted to be a man (both perfectly valid reasons). Instead, it's likely that Joan wore men's clothing because she was afraid she'd be raped if she didn't. According to the Joan of Arc Archive, while being held by the English she fastened her hose to her tunic with 20 cords, and her boots went all the way up to her waist and were also attached to her tunic, presumably because all that stuff would take forever for an assailant to remove. The fact that she had to do this at all was pretty repulsive since female prisoners were generally placed in the custody of nuns, but the English made an exception for her and left in the hands of soldiers instead. That was fine for them, since they could then point to her cross-dressing as evidence of heresy.

Ultimately, she was executed for wearing men's clothing

When she was captured in 1430, the English charged Joan of Arc with a bunch of seriously lame crimes that we would never dream of charging anyone with today, including witchcraft, heresy, and cross-dressing. The 70 charges were eventually reduced down to 12, though they still included cross-dressing, perhaps because that was easier to prove.

Anyway, then came a long trial that would have been humiliating, except for the part where Joan was so well-spoken and clever that her inquisitors decided to make her public trial a private one because she was making them all look stupid. After that, Joan was forced to sign a document denying that her visions were real and agreeing not to wear men's clothing anymore. Because remember, that last bit was super important.

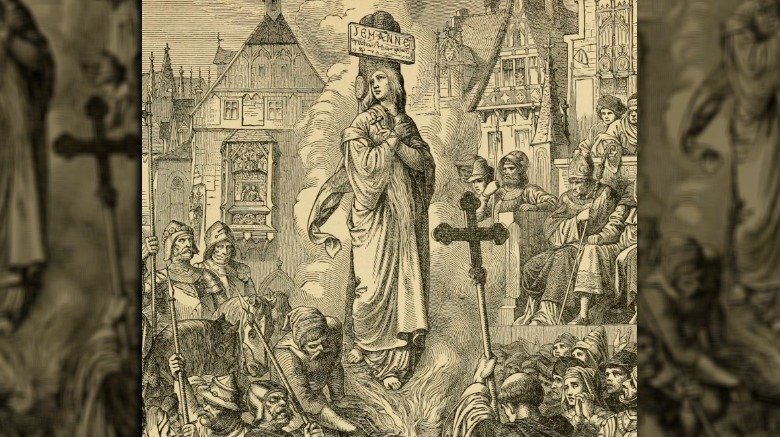

According to Mental Floss, once her life imprisonment sentence was handed down, she went back to wearing men's clothing again. She told interrogators that she did so to protect herself from the guards, aka exactly what she'd been saying all along. She also told interrogators she wasn't being totally honest when she said she didn't really hear voices, and though that certainly contributed to her ultimate fate, it seems the cross-dressing was what set everyone off again. So then the bishop in charge decided she was a relapsed heretic, and she was sentenced to death.

She probably died from heat stroke

If you're ever unlucky enough to be sentenced to death at the stake, you may hope to die of smoke inhalation or heat exhaustion, both much less painful than burning to death. If published accounts of Joan of Arc's death are to be believed, she was spared the final agony of death by fire. According to the St. Joan Center, she probably died from heat exhaustion.

As it turns out, even medieval people weren't necessarily so bloodthirsty and cruel that they always enjoyed watching the agonizing last moments of someone who was condemned to die in the most horrible way possible. Executioners were sometimes given broad authority to ease the pain of the convicted, either by slitting the unfortunate person's throat, strangling them, or piling a lot of green wood around their feet so they'd die from the smoke. There isn't any evidence that the first two things happened, but Joan almost certainly didn't die from the flames — there wasn't a single witness who said she screamed in agony, which is impossible to avoid when your skin is burning. Instead, she cried out "Jesus! Jesus!" and then she bowed her head and didn't make another sound. That's not exactly consistent with painful agony, so that's some consolation for her untimely death, but not much.

Let's burn her, and then burn her ashes, and then burn her again

Because one burning was clearly not enough, Joan of Arc was burned a second time — and then a third time. Why? Well, according to The Guardian it was especially important to the Cardinal of Winchester, who ordered the second burning, maybe because you wouldn't want anyone climbing up on the pyre and collecting souvenirs or anything.

But that wasn't enough, so she was burned a third time — although the legends about the third burning are somewhat in disagreement. Some accounts say the soldiers who were tasked with cleaning up the post-execution mess found her intact heart, still full of blood, untouched among the ashes. They desperately tried to get rid of it by dumping sulfur, oil, and charcoal on it in the hope they could get it to burn, but it stubbornly refused to become anything but a really morbid and gross symbol of its former owner's innocence. The soldiers cried out that they'd burned a saint and were doomed, and that's when they dumped her heart and her ashes into the Seine River. And so endeth the tale of Joan the Maid, except of course that's not where it ended.

Joan of Arc didn't really die, see? Now give us gifts.

Siblings are super-annoying because that's a prerequisite for sharing someone's genetics. According to the St. Joan Center, Joan had brothers, and after her death they sat around musing about how they might be able to keep a good thing going despite the tragic death of that good thing's central figure. In 1434, three years after their sister's death, a woman came forward claiming to be Joan of Arc (her real name was Claude), which was of course patently ridiculous since Joan had died in front of a huge crowd and had never once said the words, "You've got the wrong girl!" But her brothers Pierre and Jean d'Arc accepted it, and Joan of Arc lived again.

Now you might imagine they had political reasons, but no. No, Pierre and Jean were in it for the money. For six years, they traveled France and presented the imposter as the real Joan of Arc, and then happily accepted all the gifts that were lavished upon the fake heroine by an admiring population. Their ruse went all the way to the king, Charles VII, which was stupid since he'd actually known the real Joan of Arc. When Claude couldn't repeat a "secret" the real Joan had once shared with Charles, she was forced to confess.

Joan of Arc gets cleared of wrongdoing — 20 years too late

Joan's brothers might have been less than honorable, but Joan's mother came from different stock ... sort of. Anyway, Joan's mother wanted her daughter's name cleared. In 1455, she presented herself on her knees in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris and formally requested a rehabilitation for Joan of Arc.

Now you might think this emotional display opened up the hearts of all those who heard it, but not really. The whole thing was really more about making Charles VII feel better about himself. According to the St. Joan Center, several years before this he'd captured Rouen, where Joan was tried, and had decided he didn't want the stigma of heresy attached to his throne. Plus, it was pretty tough to deny that Joan of Arc was a big part of the reason why he was sitting on that throne in the first place.

Whatever the reasons, Joan got her retrial more than 20 years after her death and was finally given a formal sentence of rehabilitation. In other words, the court admitted that its predecessors, led by the English, had murdered an innocent person.

Carbon dating poops all over the relic party

Long ago, before carbon dating, you could call pretty much anything a relic. You could dig up a finger from the local cemetery and say it belonged to St. Frankenfurter, or you could soak a scrap of cloth in coffee and burn its edges and tell everyone it came from St. Barbecue. No one could really definitively disprove that your relic was real, as long as you could make a convincing argument.

According to Time, in 1867 someone was rifling around in the attic of a Paris pharmacy and found a jar of Joan of Arc relics, and for a while the Church accepted them as authentic.

But because scientists are fun-wreckers, eventually someone had to go and debunk the relics of St. Joan. Carbon-14 dating determined that the bones were from sometime between the seventh and third centuries B.C. — way, way before Joan of Arc. They also found traces of a tree resin used to embalm Egyptian mummies. The final nail in the sarcophagus was the cat bones mixed in with the human bones — black cats were sometimes thrown on the pyres of people burned at the stake, but this cat was not of European origin. So basically, the scientists figured out that Joan of Arc's relics were actually the remains of an Egyptian mummy and an Egyptian cat. That's its own kind of fun.