True Stories Behind American Tall Tales

These days, nobody pretends that a superhero like Captain America is a real dude. But back in the centuries before the internet made fact-checking into a spectator sport, a variety of zany "tall tales" lifted up the stories of ordinary mortals and made them into metahuman gods, capable of insane feats of strength, supreme marksmanship, and more. Real American history looks boring compared to the fantastical version told around campfires, where a towering giant carved out the Grand Canyon, a carnivorous "Red Ghost" haunted the desert, and the first U.S. president was such a swell guy that he never, ever lied.

Everybody knows these classic American tall tales were exaggerated. Sometimes real people embellished their achievements a little bit, sometimes biographers took creative license, and sometimes people just made wild accusations. One thing is for sure, though: The true stories behind these tall tales are even crazier than the tales themselves.

Paul Bunyan wasn't quite so tall

Decades before Ant-Man got big, the biggest guy on American shores was Paul Bunyan, a lumberjack who pulled up trees like blades of grass. When Bunyan wasn't creating the Grand Canyon with one swipe of his ax, he was chilling with his equally enormous pet ox, Babe, who for some reason had blue skin.

Was he a real guy? Nah, but History says he might've been inspired by an 1800s French-Canadian lumberjack named Fabian "Saginaw Joe" Fornier. Saginaw Joe didn't have a blue ox, but he did stand at 6 feet tall, which was pretty huge back then. Saginaw Joe was a rowdy fella who loved a good fight, a dangerous hobby which eventually got him killed during an 1875 brawl in Michigan. Over the years, folktales about big Joe seem to have merged with stories about another French-Canadian lumberjack, Bon Jean, and that's probably where the name "Bunyan" came from.

However, the composite character of Paul Bunyan was never something people actually believed in. During the early 1900s, Bunyan was probably just an inside joke that loggers casually referenced sometimes, like Mother Nature — "Look at that mountain that big ol' Bunyan made with his bare hands!" Everything changed in 1914, according to Minnesota History Magazine, when the Red River Lumber Company started using Bunyan as their mascot. The general public thought the giant lumberjack myth was fun, and he's been an icon ever since.

Calamity Jane really was tough as nails

Many of the wildest stories surrounding Calamity Jane (not pictured) are probably exaggerations made up by Jane herself, but the woman behind the legend was the same hard-drinking, sharpshooting fighter you've seen on TV. While details about Calamity Jane's life can get sketchy, Biography says her birth name was Martha Jane Cannary. Broke and orphaned at age 12, Cannary had to fend for herself, and by 1875, she landed on the infamous streets of Deadwood, South Dakota. After this point, facts get intertwined with fiction. Jane's gunslinging exploits were exaggerated in her autobiography, and novelists embellished her stories even more. In the end, she died from alcoholism at age 51.

The Independent points out that her fabled relationship with Wild Bill Hickok was probably a fabrication told by Jane herself, which then became entrenched in popular culture by 20th-century Hollywood's need for epic romances in Western movies. Later cultural depictions have portrayed Calamity Jane as everything from a feminist symbol to an LGBTQ+ icon to a tragic protagonist. As for the real woman, though? Embellishments aside, it's hard not to admire the genuine strength, attitude, and mysteriousness that made her an Old West icon in the first place.

Jackalopes are more real than you think

You'd never want to see a blood-sucking chupacabra or a hulking, hairy Bigfoot creeping around your yard, but you know what is a lot cuter? The deer-antlered rabbit known as a "jackalope," which supposedly hops around the Rocky Mountain states. SF Gate says these bizarre bunnies were first reported in 1829 by John Colter, of the Lewis and Clark expedition, but nobody took this sighting too seriously. That all changed in 1932, according to the New York Times, when a taxidermist named Douglas Herrick and his brother came home from a hunting trip and dropped a rabbit right next to some deer antlers. This gave Douglas a fun idea: He mounted the antlers on the rabbit's head, stuffed it, and named it a jackalope. The family started selling jackalopes to anyone who wanted them, and the legend took off.

What about Colter's original jackalope sighting, though? Wired points out that in real life, the cancerous Shope papillomavirus (related to HPV in humans) causes rabbits to develop hard, keratinized growths on their heads. These might resemble horns, but they're actually tumors. So it's entirely possible that people really did see jackalopes, sort of.

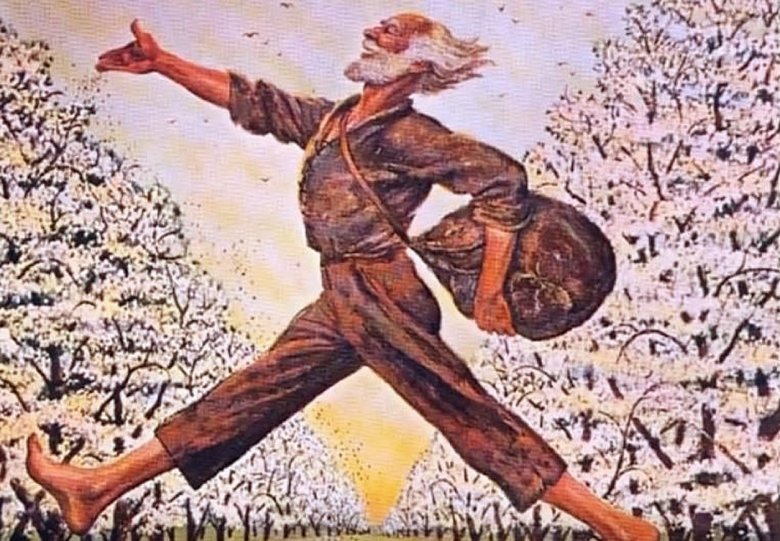

Johnny Appleseed, America's original hippie

At first glance, Johnny Appleseed seems like the most fake American legend out there. Seriously, an 1800s hippie who walks around the country barefoot, wearing dirty old rags, and planting apple trees everywhere?

Well, the exciting truth is that John "Johnny Appleseed" Chapman not only was a real guy, but he was exactly the same cheerful, vegetarian, garden-loving eccentric everyone thinks he was. According to Mental Floss, Chapman was a fervent animal rights activist who really did carry a sack of apple seeds everywhere he went. He was also a clever businessman: The reason everyone loved him was because those apples trees he planted weren't used for apple pies, but instead for hard cider, the most popular alcoholic beverage of the day. As if Johnny wasn't already awesome enough, he's also credited with inventing some of today's apple varieties, including the golden delicious. Needless to say, this guy would've fit perfectly into the 1960s, but back in the 1800s, he was quite a weirdo.

He probably didn't always wear a pot on his head, though, according to Metro. It's more likely that he preferred actual tin hats, though assuming that he did carry around a cooking pot on his travels, he might've popped it on his head from time to time. Maybe.

Which John Henry was the real one?

For generations, the hammer-wielding, superheroic railroad worker John Henry has been an African Ameican folk hero, a civil rights symbol, and a rallying figure for labor unions. Was the famous steel-driving man a real person, though? Well, there have been a few guys named John Henry who worked on railroads during the 1800s, so pinpointing the correct one is a bit tricky. One candidate is a Jamaican worker who died amid construction work in the 1890s, according to ABAA. However, the more likely candidate was John Williams Henry, a smaller man from New Jersey. According to the New York Times, this John Henry worked for the Union Army when he was a teenager, until an unfortunate run-in with the law scored him a 10-year prison sentence. Sadly, there are no records of his release, so he probably never made it back to freedom.

During his imprisonment, though, John Henry was enlisted as a construction worker in West Virginia, where he earned 25 cents a day for hard labor. John Henry was a hammer man, and while constructing the Lewis Tunnel, Henry and his coworkers were tested against steam drills, a fact that lines up with the famous ballad. The real John Henry likely died from this work, just like his mythic counterpart, but probably not from a heart attack: Instead, lung disease was the likely culprit.

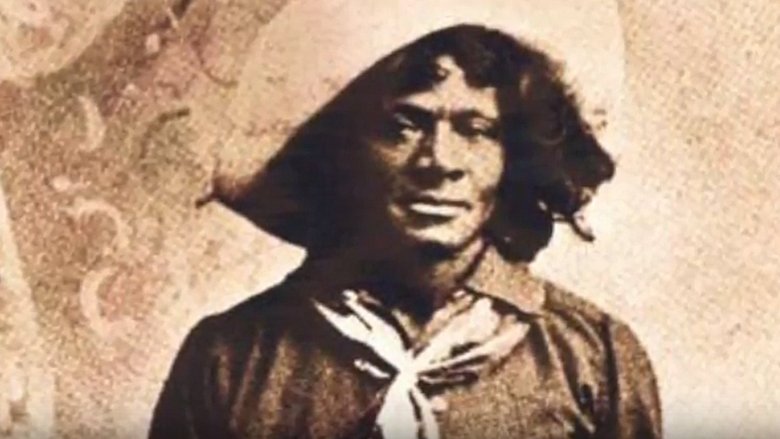

Deadwood Dick started as fiction, then became real

Fasten your seatbelt for some meta-craziness. The famous Wild West gunslinger Deadwood Dick was originally created as the fictional protagonist for a series of pulp novels written by Edward Wheeler, according to The Mythical West. These Deadwood Dick novels were the overnight Netflix binges of their day, until the author died in 1877. Usually, that would be the end of the story. Instead, though, a number of men suddenly came forward claiming to be the "real" Deadwood Dick who had supposedly "inspired" Wheeler's character. Only one of these guys truly earned the pseudonym, though, and that was Nat Love.

Born a slave, Love grew up to become a free cowboy, and reportedly got the nickname Deadwood Dick after winning an 1867 roping contest in Deadwood. Though Nat Love certainly lived the sort of life they make movies about, NPR says a lot of the myths associated with the Deadwood Dick character today were probably playful tall tales told by Love himself. These stories entered popular culture when Love published his autobiography, The Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as "Deadwood Dick." So yes, those fictional Deadwood Dick books inspired an embellished, autobiographical Deadwood Dick book. Feeling dizzy?

Was George Washington really the most honest kid ever?

Have you ever met a 6-year-old boy who would do something wrong, get accused of doing it, and then proudly admit to his father that "I cannot tell a lie" before fessing up? It'd be nice if all first graders were so forthright, but the oft-told parable of little George Washington and the cherry tree sounds an awful lot like historical revisionism ... and yes, that's exactly what it is. According to the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, the cherry tree story was dreamed up by minister Mason Locke Weems, who published a biography of the first U.S. president shortly after his death. The cherry tree wasn't part of Weems' original manuscript, quietly inserted five editions later in 1806. It wasn't the only saintly story Weems made up about old George, but for some reason, this particular tale never died.

Yes, this famous little story about the benefits of honesty is, in fact, as dishonest as a car salesman. At least Mr. Weems didn't claim that he could "never tell a lie."

Davy Crockett wasn't so great

"The Ballad of Davy Crockett" might describe its titular figure as king of the wild frontier, but the real Crockett was probably more like that annoying guy at the bar who exaggerates his accomplishments to everyone who'll listen. Forget about fighting bears as a kid, valiant wartime efforts, or his alleged reputation as a defender of Native American rights: According to Time, Crockett's participation in the Creek War wasn't a big deal, and the one major "battle" he bragged about was really just a ruthless, mass slaughter of Native Americans. The New Yorker also points out that Crockett, as well as all those other guys who got killed at the Alamo, were slave owners, not heroes.

To Crockett's credit, during his time as a U.S. Congressman, he did vote against Andrew Jackson's horrific 1830 Indian Removal Act, which forced the Native Americans to relocate against their will. For the most part, though, Crockett's time in Congress was seen as ineffectual, and after three terms he was voted out. How did this guy get so ridiculously glorified? Well, according to History, his colorful personality as a symbol of the "wild frontier" made him a pretty unique politician. He had a lot of charisma, and he liked telling tall tales about himself, particularly in his autobiography. Pulp novelists found him a fun protagonist to work with, and their fictional stories eventually got conflated with the real person.

Molly Pitcher probably had a different name

It would be one thing if a kid named Kristen Doctor became a physician, or if Kyle Painter became an artist. But honestly, what are the odds that a woman named Molly Pitcher would become famous for carrying pitchers of water to a bunch of bloody, sweaty soldiers in the American Revolution?

If this woman was real, according to Biography, historians are pretty sure "Molly Pitcher" was just a nickname. It's been argued that the mythic figure might be a composite of several women who assisted in wartime efforts, including Margaret Corbin — who soldiers often referred to as Captain Molly — and particularly Mary Ludwig Hays, who is often credited as "the real Molly Pitcher." What is known about Hays' life certainly lines up with the fabled story, and it's believed she even operated a cannon at one point, just like "Molly Pitcher" did in the artwork above. One witness claimed to have seen a cannonball blast right between Hays' legs, ripping up her petticoat, at which point Hays simply commented that she was glad that the shot hadn't passed a bit higher. Hays' bravery in wartime was honored in 1822, a decade before her death.

Beware the carnivorous Red Ghost

Between cacti and coyotes, the Arizona desert can be a scary place. But to Wild West cowboys, the scariest thing of all was a demonic monster they called the Red Ghost. Described as a 30-foot-tall behemoth, the Red Ghost devoured humans, grizzly bears, and anything else in its path. Rumors of its viciousness spread all the way to the East Coast. Here's the thing, though: according to the Smithsonian, the Red Ghost was actually just a bunch of camels.

If you're wondering why the heck camels got into the southwest United States, well, good question. You can blame future Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who during his tenure as U.S. Secretary of War thought it'd be a marvelous idea to import camels to transport goods for the Army. The experiment was expensive and unpopular, so most of the camels ended up getting auctioned off. A few of them escaped to the wild, where they could roam the Arizona wilderness and freak out the locals. Considering how weird it would be to see a camel stride through your yard in the 1880s, we can excuse some of this Red Ghost silliness. The whole human-eating part, though? That's a little overboard.

Pecos Bill is fakelore, not folklore

Popular culture paints Pecos Bill as one of the biggest heroes of Old West mythology. Unfortunately, this raised-by-coyotes cowboy with a snake for a whip was also one of the fakest myths out there. While a superhuman cowboy like Pecos Bill certainly seems like he could've been based on a real person, or at least an old campfire story, the truth is Pecos Bill was most likely just a fictional character invented for a 1923 story by journalist Edward O'Reilly, according to the Texas Folklore Society. Though O'Reilly maintained that his Pecos Bill character was derived from old cowboy stories he'd heard as a kid, there's no evidence that any oral tradition predated 1923. Sure, one could arguably say Pecos Bill became folklore after O'Reilly's story, but that's a different discussion altogether. The biggest problem with O'Reilly's claim that Pecos Bill stemmed from old cowboy stories is that he wasn't too consistent about the matter. Years later, according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, when another writer plagiarized the 1923 story, O'Reilly sued. His reasoning? Because, in his own words, he invented the character. Oops.

Either way, Pecos Bill wasn't a real guy, and it's debatable if he even counts as a genuine piece of folklore. But hey, that doesn't mean you can't enjoy the stories about him.