Facts About Typhoid Mary The Average Person Doesn't Know

Mary Mallon should have lived the American dream. She was born in 1869 in Ireland and like so many people in that period looked to the United States for a better life. She immigrated sometime in the 1880s and settled in New York City, that concrete jungle where dreams are made, the melting pot that welcomes other countries' tired and poor. She moved in with relatives. She got a good job. And then she started killing people.

Soon Mary Mallon was no more, and Typhoid Mary took her place. She would go down in history not as one of thousands of hardworking immigrants just trying to get by, but as a dirty, disease-ridden, cold-blooded killer. Popular culture would even lend her name to a Marvel supervillain, a mentally ill assassin. There are better ways to be remembered.

But what do most people actually know about Typhoid Mary? She had typhoid, sure. She gave it to other people, obviously. Yet the details of her fascinating and ethically complicated story are often overlooked.

She only killed three people (that we know of)

When your nickname becomes popular shorthand for someone who spreads not only disease, but any kind of undesirable trait, you know you've failed completely in the reputation department. Mary Mallon is remembered as someone with awesome power, who could probably just point at people in the street and make them keel over with typhoid. But in reality, rather than the thousands of bodies left in her wake that people envision, she was responsible for the deaths of just three people. The infamous Typhoid Mary couldn't even manage to take out a full barbershop quartet.

Snopes says she also only infected 33 people total, although other sources put the number slightly higher. (She often changed her name when she switched jobs, which complicates estimates.) Sure, it's not great to have the ability to strike down even a couple dozen people with a deadly disease, but her contribution to the overall typhoid problem was tiny. In 1906, the year she was first arrested, 3,000 people were infected and 600 died in New York State alone.

She wasn't even the deadliest typhoid carrier that we know of from the period. According to Thought Co, authorities at the time were also aware of Tony Labella, another seemingly healthy person who infected 122 people and killed five. Yet he saw none of the punishment Mary Mallon would suffer and wouldn't be remembered as a person crawling with disease, even though "Typhoid Tony" has a much better ring to it.

She wasn't medically special, at all

By the turn of the 20th century, when Mary Mallon was typhoiding up the place, science had advanced a lot. According to one research paper, doctors understood diseases were spread by germs, and they even knew typhoid specifically was spread through infected excrement. What they didn't know was that people with none of the symptoms of typhoid themselves could still spread it to other people. Mallon was one of these seemingly healthy carriers.

But she was far from alone. It wasn't just her and Tony Labella who were walking germ factories. There was also Alphonse Cotils, a baker whose bread could kill you dead. And an Adirondack guide named John who infected 36 people. (Two died.) And so on and so on. In fact, Smithsonian Magazine reports that today we know up to 6 percent of people who come down with typhoid and survive can spread the disease to others long after they recover. That means that because of the thousands of cases in New York every year at the time, hundreds of people walking the streets with Mary Mallon also suddenly had a deadly superpower they knew nothing about.

Yet for some reason, even though she was just one of thousands, even though we know specific names of other carriers, and even though she wasn't even the deadliest, it was Mallon who became Typhoid Mary. Why? All the crazy little details.

She was a fabulous cook, but a terrible hand washer

Like most Irish immigrants at the time, Mary Mallon had to fend for herself from a young age. But she "craved independence," wasn't afraid of work, and started doing domestic labor. At some point she learned all about cooking. It turned out she had a bit of a talent and was soon getting hired as a cook in some of the best houses in Manhattan.

In a period when many immigrants were dirt poor, Mallon was making the princely sum of $45 a month, according to the Long Island Press. Rich families were willing to pay out the nose to get edible stuff on their table. And Mallon must have delivered, even if she often included something a little extra.

The problem was she didn't have proper hygiene. She never felt sick, so Mallon didn't see the point in washing her hands. Since the typhoid bug comes out in your poo, that means when she wiped she got it on her hands and then spread it to food. A lot of the time this didn't matter, even if it is super gross. The heat of cooking kills the germs so even if they were eating poo particles, the people enjoying her meals wouldn't actually get typhoid. But Mallon's specialty was dessert, especially ice cream with peaches. That doesn't get cooked, so typhoid lives there happily, ready to infect the person who puts it in their mouth. Historians and doctors are pretty sure that's how she spread the disease.

People only got concerned when wealthy families got sick

Typhoid wasn't a rare ailment. The Straight Dope says during the Civil War, more soldiers died of typhoid and dysentery than bullets and cannons. People were coming down with it all the time, and plenty of them shuffled off the mortal coil because of it. So the couple dozen people Mallon was infecting weren't that notable –- except they were totally loaded.

Popular opinion held that rich people did not get typhoid. It was a disease of the poor. Since you got it from interacting with poo, it was expected that those unsanitary, unwashed masses would obviously fall victim at some point. Their lack of money probably meant they would take a dump in the street and then roll around in it. You know what poor people are like.

But suddenly there were these regular outbreaks in really wealthy families. There had to be a reason. According to the Irish Post, when half of banker Charles Warren's household got typhoid at the same time, he hired Dr. George Soper to find out why. Soper, a sanitary engineer, interviewed all the rich families that had come down with it and discovered a common entity: an unmarried, heavyset, Irish cook of around 40. But they all said she had never been sick herself. Soper theorized, and was right, that asymptomatic carriers of typhoid could exist. Mallon was the first one ever known about, and now he had to prove it. And to do that, he needed her feces.

She didn't go quietly

How would you feel if some random guy showed up at your work one day and said you needed to hand over your poop? If you were anything like Mary Mallon, you would get really pissed off. When Soper arrived at her employer's Park Avenue house and explained his theory that she was killing people with typhoid and to be sure he needed samples of her blood, feces, and urine, she grabbed a carving knife and started advancing on him. Thought Co says Soper later recorded that he ran out of the house and felt "lucky to escape."

On his next try he cornered Mallon at her own house and brought another doctor as backup. Mary needed no weapon — she just screamed expletives at them until they fled. Soper could see this was going to be difficult. So he took all his evidence to the New York City Health Department. They agreed Mallon must be making people sick and loaned him a few police officers.

By now Mallon was expecting them. She attacked the group with a kitchen fork and managed to run out the door and disappear. It took them five hours of searching before they found her in a neighbor's closet. Despite trying to calmly explain the situation to her again, she kept swearing and hitting them. Finally, a policeman had to pick her up and put her in an ambulance. She still resisted, and someone had to sit on her while she was transported.

She spent decades in isolation

Mary Mallon (above, left) was basically arrested in the name of public health. She was put in isolation and forced to hand over the bodily fluids she had so aggressively defended. They came back positive for typhoid, proving Soper's theory. Mallon was a walking contagion, even though she wasn't sick herself.

According to PBS, she was given an ultimatum: have her gallbladder removed (that's where doctors believed typhoid hung out) or stay in isolation forever. Abdominal surgery was unbelievably dangerous in 1907, so she would have been risking death. She picked quarantine, and they left her in a tiny brick bungalow on an island, held indefinitely without trial.

She was not thrilled about this, as you might expect. The Smithsonian Magazine says she wrote her lawyer after a few years inside, saying she felt like a "kidnapped woman" and a "peep show for everybody." That wasn't paranoia: io9 reports she was sometimes shown off to visitors. Other times she faced neglect. And they kept testing the stuff that came out of her, making her hand over 163 samples in three years.

But she was eventually offered freedom, with a catch: She had to swear never to be a cook again. She agreed and started working in a laundry. But it didn't pay as much, and she returned to the kitchen. When there was a huge typhoid outbreak at her new job, she changed her name and got hired somewhere else. After a couple rounds of that, she was arrested and held for 23 more years until she died.

She became a huge celebrity

Almost as soon as she was apprehended, Mallon became famous. Within a year of her arrest the phrase "typhoid Mary" appeared in no less than the Journal of the American Medical Association, according to the book Death in the Pot. Only months later, a textbook on the disease capitalized it and the name stuck. That would be like if your doctor was a huge gossip and the whole world suddenly knew you as "Herpes Steve."

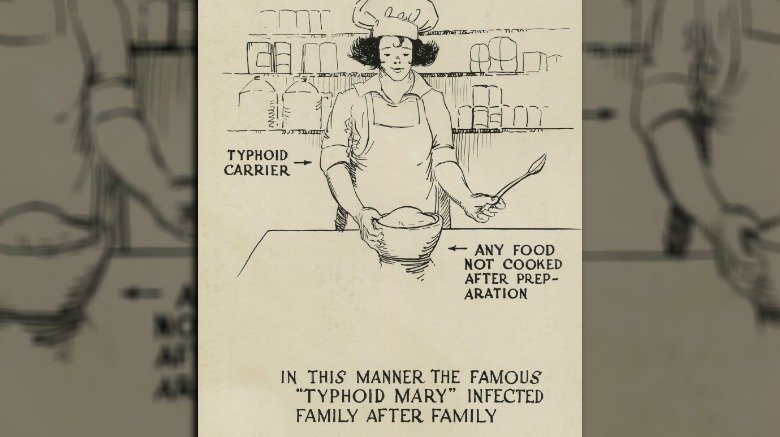

In 1909 the papers got wind of the lady who was making everyone sick and introduced her to the world in the worst way. The New York American covered her in a huge two-page spread, where Mallon was made to look about as bad as possible. Called "Typhoid Mary" in the headline, it also said she was "The Most Dangerous Woman in America." Smaller headlines announced that she left "Death and Destruction" in her wake and that "She Breeds Typhoid Fever Germs and Scatters Them Wherever She Goes." A giant drawing accompanied all this, of Mallon cracking human skulls into a frying pan.

The story was a sensation and others added to it. PBS says more than one newspaper reported she was "crawling with typhoid bugs." An article in the Annals of Gastroenterology reports she appeared in mean-spirited cartoons and became the butt of jokes. The LA Times described her as "infamous" at the time.

William Randolph Hearst might have bankrolled her legal bills

Despite the fact that she was being bashed all over the press, some public opinion was on Mallon's side. It was concerning that the government could just grab seemingly healthy people off the street and lock them up forever without trial. So two years after her initial detention, Death in the Pot says she sued New York City for wrongful arrest.

According to History, Mallon was prepared. She had submitted poop samples to a private lab and they had supposedly come back negative for typhoid. She had a good lawyer. And she had a good defense. "I never had typhoid in my life and have always been healthy," she said, asking, "Why should I be banished like a leper and compelled to live in solitary confinement with only a dog for a companion?" (They had given her a fox terrier, possibly to take the edge off the whole inhumane situation.)

Mallon had earned good wages, but historians still wonder how she paid for all this. One theory is that newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst helped. He owned the New York American, which had broken her story, and she was selling a lot of papers for him. It wasn't out of character for him to help; he had done it before for "other people whose stories interested his newspaper's readers." Plus, more headlines...

Regardless, that was early on, after her first arrest. As we mentioned, she lost her case, was released a year later, and eventually reoffended.

She always claimed she wasn't sick, but...

Mallon claimed passionately until the day she died that she was not a carrier of typhoid. She swore she had never had the disease so there was no way she could be passing it on. What she might not have understood, or perhaps no one explained to her, was that some people get such mild cases of typhoid that they just get flu-like symptoms. It is very possible she had such a case when she was a child in Ireland and didn't connect it to the deadly disease.

It's easy to feel bad for Mallon because of the treatment she received even though she truly thought she was blameless. Or did she? Typhoid Mary may have talked a good game, but her actions show she might have known something was going on.

io9 points out that for someone who swore they were innocent, Mallon sure acted like a guilty person. She must have noticed that people tended to get sick within weeks of her starting to cook for them. She certainly quickly quit her job and snuck away quietly each time it happened, not leaving a forwarding address. She never had a problem getting another position, but she also always conveniently failed to mention she left her last job because everyone came down with a deadly disease you get from contaminated food and water. Add in the fake names, and you've got a recipe (ba-dum) for disaster (tish).

Her treatment may have been worse than other people's because of prejudice

Unquestionably, Mary Mallon was a danger to public health once she refused to stop cooking. But it's shocking how drastically differently the government treated her compared to thousands of other carriers.

Thought Co reports one historian believes it came down almost completely to a perfect storm of demographics. And the author of a novel on Mallon wrote in Time that the case was "as much about gender and class prejudices as it was about typhoid."

Mallon was an Irish immigrant at a time when people still mostly hated them. She was a single, working woman, and worse than that she was a woman with a temper. There was a general bias against and distrust of domestic servants. All this combined with the fact that carriers of disease are seen as unclean was probably enough to give her special pariah status. Even the great Dr. Soper who cracked the case and figured out her asymptomatic situation has been accused of bias in his investigation. Anthony Bourdain wrote (via the New York Times) that some historians claim Soper was "racist, sexist, and far too influenced by the prejudices of his class" while just looking for "the first likely Irish woman he could clap the manacles on."

Whatever the reason, there was definitely something about Typhoid Mary that made her stick in the public consciousness all this time.