Camp Lejeune's Water Contamination Fiasco Explained

It's not hard to believe that the United States government was complicit in poisoning its own military. Veterans have often come back from overseas with various ailments that the U.S. government proceeds to deny all responsibility for. But this usually involves people in the military being in another country, so some might be surprised to hear that the U.S. government has been involved in covering up a mass poisoning in its own backyard.

The conspiracy behind covering up the mass water contamination at Camp Lejeune, a Marine Corps training base, was long attributed to the idea that federal regulations on environmental protections didn't exist for a long time. But when it was finally revealed that numerous government agencies had known and ignored the fact that the water contamination was detrimental to the health of the people drinking it, it became clear that it wasn't just an issue of ignorance.

Meanwhile, up to a million people had to wait decades to find out that the water they'd used for years had been poisoning them with carcinogens. The extent of the mass poisoning is unclear, but as of 2023, the water contamination at Camp Lejeune continues to be known as the the worst public drinking water contamination in the nation's history." This is Camp Lejeune's water contamination fiasco explained.

What was Camp Lejeune?

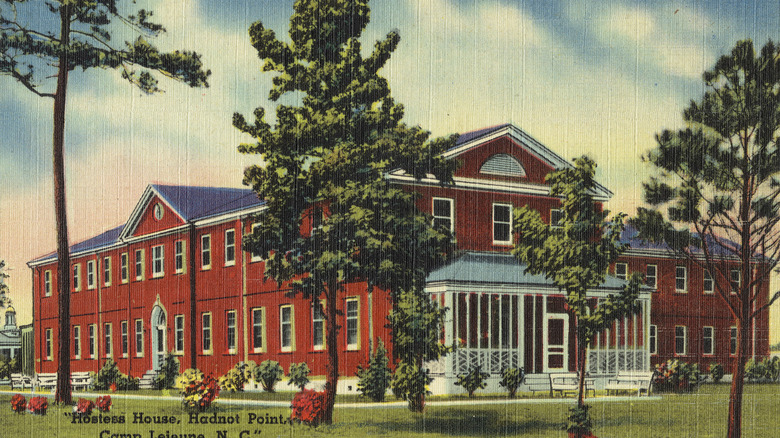

Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune is a training camp for the U.S. Marine Corps located in Jacksonville, North Carolina. Created in 1942 and originally known as Marine Barracks Camp Lejeune, the camp was established so that Marines in the United States could train in amphibious settings on the East Coast.

In total, it cost over $20 million for the construction of Camp Lejeune, and the original camp took up 11,000 acres along the coast of North Carolina. Since then, Camp Lejeune has expanded to 156,000 acres. The camp was also associated with several satellite facilities, including Montford Point, which was the first Marines training base for Black people. Also, as a satellite facility, it was segregated, according to "Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military," both Montford Point and Camp Lejeune were associated with Black Marines.

Over one million people lived and worked at Camp Lejeune during the second half of the 20th century. But what many of them didn't know at the time was that the water they were using at Camp Lejeune was severely contaminated. At Camp Lejeune, there were eight water systems with 100 wells that supplied water to the base. But from at least 1953 to 1987, three of the water systems were severely contaminated with volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

Featured image by Boston Public Library via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Water at Camp Lejeune

The Hadnot Point water plant, the Tarawa Terrace water plant, and the Holcomb Boulevard water plant distributed contaminated water for many years, with one plant estimated to have done so for more than three decades. While Hadnot Point and Tarawa Terrace both suffered from contamination, Holcomb Boulevard's water wells never actually got contaminated themselves. However, the Holcomb Boulevard water treatment plant sometimes used contaminated water from Hadnot Point, and ended up distributing the contaminated water to a wider area as a result.

The contamination came from several places. One was a dry cleaning facility off-base called ABC One-House Cleaners, which was located less than 1,000 feet from a water well used by Camp Lejeune, according to "Polluted Earth" by Alexander Gates. Another source of contamination were the underground gasoline storage tanks left behind by the military, as well as other waste disposal areas where the chemical waste wasn't properly disposed of by the military. These contaminants ranged from things like gasoline to chemicals like TCE, or trichloroethylene, which is used by the military as an engine degreaser. In fact, the military buried all kinds of waste in the area, ranging from chemical waste to dead dogs that they'd used in tests.

But although the water used by the residents and workers at Camp Lejeune was contaminated for years, the extent of the contamination wouldn't be discovered until the 1980s.

Testing in the 1980s

In 1979, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established the first regulations regarding trihalomethanes (THMs). According to the EPA, the regulation established that no more than 100 micrograms per liter of chloroform, BDCM, DBCM, and bromoform combined was allowed in public drinking water that reached over 10,000 people.

Although Camp Lejeune's water wells weren't considered to be public drinking water supplies, Camp Lejeune started testing their water for THMs in 1980. This may have been done in response to the fact that the EPA called Camp Lejeune a "major polluter" in the 1970s. The Marines had until then been following drinking water regulations that had been issued in the 1960s by the Department of the Navy's Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

During the tests, it was found that accurate readings of the THMs couldn't even be found because there was such a high quantity of VOCs that it obscured accurate readings, according to DttP: Documents to the People. And the levels of VOCs were extremely high. The U.S. Army Environmental Hygiene Agency also conducted tests in 1981, which warned in a note: "Water is highly contaminated with other chlorinated hydrocarbons," per Stars and Stripes.

The water was highly contaminated

The United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency repeatedly found that the drinking water at Camp Lejeune was heavily contaminated, and some of the samples of water came from places like the hospital's emergency room on base. In "Polluted Earth," Alexander Gates writes that while the limit for things like trichloroethylene was 5 parts per billion (ppb), the drinking water showed levels up to 1,400 ppb. Ultimately it was found that people at Camp Lejeune were drinking, bathing in, and using water that was contaminated with pollutants that were up to 3,400 times the acceptable level stated by the EPA. Even the relatively smaller contaminations were over 280 times the acceptable level recommended by the EPA.

The off-base contamination from the dry cleaning facility is believed to have started in 1953, when the facility opened, but the on-base contamination from improper waste disposal by the Marines and the Navy had likely been going on since the base camp was established. And ultimately, it's unknown exactly how widespread and how intense the water contamination was.

In 1997, it was also finally reported that the water was also contaminated with benzene. But even this too had been known by the Marines, and had been willfully underreported during a federal health report, according to AP (via CBS News). It's estimated that around 1,500 gallons of benzene-containing gasoline were leaked into the groundwater every month.

Ignoring reports and warnings

The United States Marine Corps was informed of the contamination in the drinking water in 1981, after the first series of tests were conducted. But there was absolutely no response or action taken as a result. Samples continued to be taken throughout the early 1980s, and in 1982 were taken as often as monthly, writes DttP: Documents to the People. Unfortunately, the samples were often widely different at times as well, making it difficult to figure out the extent of the contamination. This discrepancy was thought to be caused by the sporadic mixture of water from uncontaminated wells.

And although the Marine Corps was required to inform the North Carolina Water Supply Branch about the contaminations, no such mention of the contaminations were made. This didn't even happen in 1983, when the Marine Corps gave a report to the EPA that was supposed to be about cleaning up waste sites. In late 1984, the Marine Corps finally acknowledged that there had been contamination with carcinogenic chemicals at Camp Lejeune. However, even after this acknowledgment, staff at the base denied that people had been directly exposed to the pollutants.

The Marine Corps were not the only ones who tried to ignore and hide evidence of severe contamination in the water. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry also released a report claiming that the water contamination didn't cause any health problems as late as 1997.

Closing the contaminated wells

In 1985, five years after reports of contamination first started appearing, some of the more polluted water wells were closed by the United States Marine Corps. CNN reports that a letter was sent to residents that had been receiving water from the wells informing them of the closure, further stating: ".. minute (trace) amounts of several organic chemicals have been detected in the water."

But even after the wells were closed, some of them continued to be used. Even the most contaminated wells continued to be used up through 1987, at times when the water levels at the other wells were too low. All of the contaminated wells wouldn't be permanently closed until 1987. By that point, up to one million people had been exposed to carcinogenic chemicals for over 30 years.

And while trying to surreptitiously close the wells, the Marine Corps continued to deny that there was any problem with the water at Camp Lejeune. As claimed by a newsletter on the base in 1984: "[Camp Lejeune] did not expect to expose anyone to any contaminants" (via DttP: Documents to the People). And any information about the contamination was limited to those who were still living at Camp Lejeune: Many who'd moved away from Camp Lejeune wouldn't find out about the contamination that they'd been exposed to until years later.

Clean-up at Camp Lejeune

In October 1989, Camp Lejeune was declared a Superfund by the EPA, which gave the EPA authority over the clean-up at the base. But because the clean-up of the contaminated water wells stemmed from multiple sources, a single mass clean-up couldn't be coordinated and instead, each source of contamination had to be independently addressed. And the United States Marine Corps reportedly repeatedly impeded the efforts to investigate and clean up the contaminated sites.

Most of the contamination at Camp Lejeune was cleaned up between 1992 and 2001. And by 1992, both TCE and PCE had been federally regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act. During this time, the EPA stated that a groundwater treatment system was installed in addition to getting rid of contaminated soils and leaking storage tanks. But most of this clean up was to deal with the most time-sensitive contaminations. Ultimately, much of the clean-up and prevention implementation was ongoing until 2022.

Cleared of any wrongdoing

Over the course of 10 years, numerous federal agencies, including the EPA and the General Accountability Office, investigated the water contamination at Camp Lejeune. The EPA investigated actions related to the water contamination twice, but neither investigation yielded anything. And although one of the investigations was referred to the Department of Justice, no one was ever charged with criminal wrongdoing.

The United States Marine Corps also conducted an internal investigation into the water contamination, which subsequently stated: "... the Marine Corps leadership acted responsibly and saw no evidence of Marine Corps attempts to cover up information that indicated contamination in Camp Lejeune drinking water."

However, none of these investigations were into the health issues caused by the contamination. Instead, they were focused on how the Marine Corps dealt with the knowledge of the contamination. The only thing that was acknowledged in terms of culpability was that the Navy should have offered more support to the Marine Corps towards understanding the contamination. And according to a 2007 report by the Government Accountability Office, although the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry was theoretically best equipped to study and address the contamination, its work may have been hindered both by lack of funding and obstruction by the Department of Defense.

Subsequent diseases

The chemicals that contaminated the water at Camp Lejeune, including PCEs, TCEs, and benzene, can cause a wide variety of health issues to people that are exposed to them. According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), these health effects can range from eye defects and birth defects to various cancers and impaired neurological functions. And despite the fact that the United States Marine Corps underplayed the dangers from the toxic exposure for years, a 2023 study from JAMA Neurology found that rates of Parkinson's disease were 70% higher in veterans who had been stationed at Camp Lejeune than at other Marine Corps bases.

Although it's known that up to one million people were exposed to the contaminated water, it's unclear exactly how many people died as a result. According to a report by the ATSDR, civilian workers at Camp Lejeune reportedly had up to 10% higher mortality rates associated with cancers, kidney diseases, and Parkinson's disease than civilian workers at other Marine Corps camps with uncontaminated water supplies. Many people who lived on the base also experienced miscarriages while they were living at Camp Lejeune.

However, in the Camp Lejeune Justice Act that was passed in 2022, the Department of Veterans Affairs only recognizes seven diseases as being directly linked to toxic exposure. The diseases acknowledged by the VA as having a presumptive service connection, and which give people the right to sue, include various cancers and Parkinson's disease.

Poisoned patriots

Scientists and observers have described the water contamination at Camp Lejeune as the worst public drinking water contamination in U.S. history. But the mass poisoning wouldn't be acknowledged by the United States government until 2007, when Congress formally investigated the contamination through a House Energy and Commerce panel, where the victims of the mass poisoning were referred to as "Poisoned Patriots." But it wouldn't be until 2012, when President Barack Obama signed the Honoring America's Veterans and Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act, that those who'd been exposed to the toxic water received any sort of aid for their suffering.

Another hearing was held in 2010, during which the United States Marine Corps was confronted with overwhelming evidence that they'd covered up their knowledge of the toxic contamination for years. During the hearings, Marine Major General Payne claimed: "... we were lulled into a sense of complacency or at least a lack of urgency by the fact that we were not out of compliance," per the U.S. House of Representatives.

The culpability was clear. In 2009, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry even released a statement saying that their 1997 health assessment — which claimed that the water was fine — had been inaccurate.

Camp Lejeune lawsuits

The first lawsuit against the United States government related to the contamination at Camp Lejeune was filed in 2009 by Laura Jones. Jones lived at Camp Lejeune while her husband was stationed there from 1980 to 1983, and subsequently developed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, which she asserts was caused by the contaminated water at the base. Although the United States government has tried to have the case dismissed numerous times, as of 2023, the legal case is ongoing.

In 2019, there were still roughly 4,500 tort claims pending against the Department of the Navy, all of which were denied by the Navy. But after President Joe Biden signed the Camp Lejeune Justice Act (CLJA) of 2022, which allowed veterans to file lawsuits regarding their experience with the contamination at Camp Lejeune, over 65,000 people filed an administrative claim with the Navy. According to the CLJA, people can also file a federal lawsuit six months after filing the administrative claim. As of May 2023, over 900 lawsuits have been filed regarding the contamination at Camp Lejeune, which Reuters reports is three times more than the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina is used to dealing with.

However, the lawsuits may end up penalizing veterans rather than helping them, specifically those who have already received healthcare and/or disability benefits as a result of the Camp Lejeune water contamination. As the VA has stated (via the Marine Corps Times), these benefits will be deducted from any future payout.