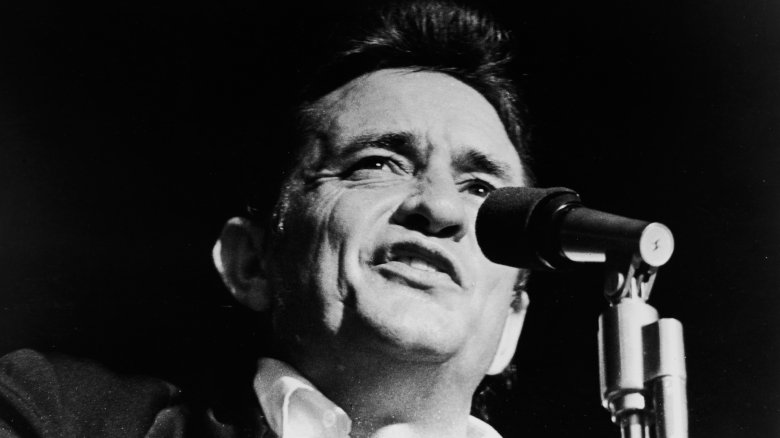

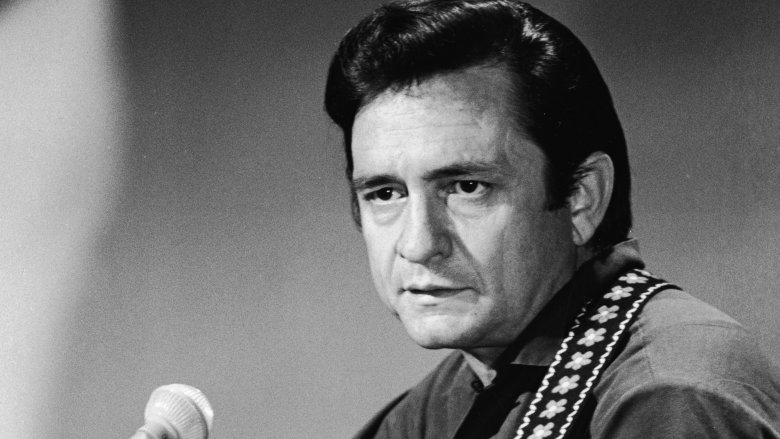

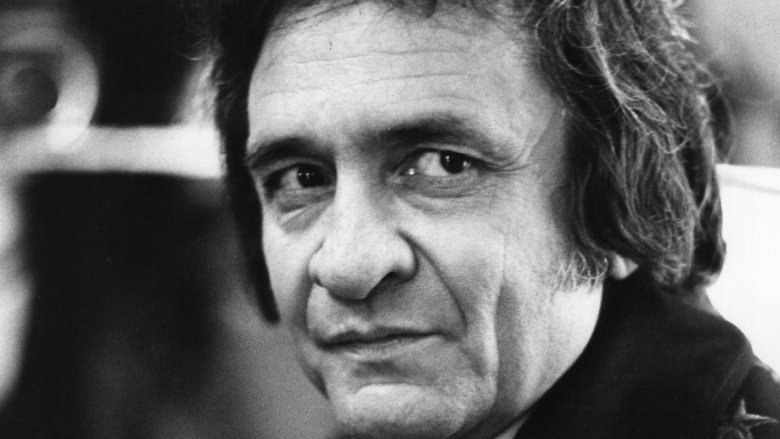

The Tragic, Real-Life Story Of Johnny Cash

Kris Kristofferson once wrote a song about Johnny Cash that contained the line, "He's a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction." That's a pretty insightful way of saying that Johnny Cash, for all his strength and all the respect he commanded, was a man who had little trouble over the years succumbing to his temptations, testing the faith and respect others had in him. He was one of the greatest artists country music has ever produced, but at one time he took enough amphetamine pills to dry his throat to the point where he couldn't sing. He was a man who spoke often and lovingly about his family, but he ruined one marriage with indulgence and adultery, and tested the resolve of his second wife when he slipped back into old habits. He was a man of mountainous religious faith, but at his darkest moment, he is said to have crawled into a cave, never feeling farther from his God.

People cared about him because, at heart, he was a good man of prodigious talent and endless capacity for kindness to others, while simultaneously wearing himself down with drugs and alcohol. He lost people close to him, some early on, and survived a hardscrabble childhood marked by poverty and hard labor. He might have been that walking contradiction, but his life was one of breathtaking highs and unfathomable lows. This is the tragic, real-life story of Johnny Cash.

He started working as a child

Johnny Cash was the fourth of seven children, born February 26, 1932, in Kingsland, Ark. to Ray and Carrie Cash. In his memoir, Johnny Cash: The Autobiography, Cash recalled that the house in which he was born "didn't have any windows; in winter my mother hung blankets or whatever she could find." The Depression hit the Cash family hard, but when Johnny, who was actually named J.R., was three years old, they moved to the Dyess Colony in northeast Arkansas, taking part in a federal farming program in which the family farmed 20 acres of cotton and other crops. When he was five, Johnny started working in the fields alongside his parents and siblings.

He started at first as a water boy, carrying drinking water out to his family. By the time he was eight, he was picking cotton with them, dragging a heavy canvas sack that started empty, but by the end of the day held 200 or more pounds of cotton. "It wasn't complicated," Cash noted in his memoir. "You just parked the wagon at one end of the rows and went to it." He said the work was exhausting and painful; he had back pain, even as a child, and the cotton bolls he picked were sharp, which cut his hands. "[W]e just worked and worked and worked," he remembered.

His brother's death had a major impact on him

One Saturday morning when Johnny Cash was 12, he begged his brother Jack, two years his senior, to go fishing. Jack declined; he had a job cutting oak trees into posts, working at a table saw — three dollars for a day's labor. In his autobiography, Cash remembered begging his brother to skip the work and head down to their fishing hole, but Jack said no. Cash went by himself, but the time he spent there was listless, and he eventually left and headed for home. His father met him on the road, in a panic — there had been an accident, and Jack was badly hurt. He had been pulled into the saw and cut from his ribs through his stomach to his groin. Jack lingered for close to a week before finally succumbing. According to Biography, Johnny helped dig Jack's grave and attended his brother's funeral in clothes dirtied from that labor.

"After Jack's death, I felt like I'd died, too," Cash remembered, adding, "I had no other friend." As he grew up, he felt his brother's influence on him as he faced many decisions. "The most important question in ... my life," Cash wrote, "has been 'Which is Jack's way? Which direction would he have taken?'" Jack also showed up in Cash's dreams from time to time — usually when Cash was either doing something he shouldn't have been doing, or about to do something he shouldn't have been doing. In the dreams, Jack would know what Cash wanted to do, and would look at him with an admonishing smile. Cash wrote, "There's no fooling Jack."

Johnny Cash struggled with addiction

In 1961, Johnny Cash and his wife Vivian moved with their four daughters to Casitas Springs, California, where Vivian hoped he could be convinced to give up the pills and alcohol that had become an integral and dangerous part of his life. Instead, his problems got worse, particularly with amphetamines. "In my pre-teen years," said his daughter Rosanne, "my father's drug addiction was really consuming him and my parents' marriage. ... There was just this background tension and anxiety to all of those years." The pills would leave his voice a mere croak; it got to the point where he was having trouble performing, if he showed up to the gigs at all.

Eventually, he stopped taking amphetamines, but his vigilance would sometimes wane. He was an addict and an alcoholic. He couldn't take just one pill; he needed a handful. He couldn't have just one drink; he needed to empty out his hotel room's mini-bar. His struggles continued in the '80s, when he was prescribed pain medication for various surgeries and illnesses and continued to take them after he no longer needed them. In his autobiography, he recalled being on morphine and valium after a surgery and hallucinating commandos setting up bombs in his hospital room. Cash's struggles required a steadying influence in his life; when he couldn't manage himself, he leaned on his second wife, June.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

His first wife filed for divorce

When Johnny Cash was in the Air Force, he incessantly wrote letters to Vivian Liberto, whom he had met at a roller rink, and would marry once he left the service. Their domestic situation was a normal one (he got a job and they started a family), until he started playing and recording music. He had a hit record, "Cry, Cry, Cry," that compelled him to go out on tour, which spelled trouble for their marriage. Eventually, according to biographer Steve Turner, Cash was away from home up to 80 percent of the year, travelling some 300,000 miles in the process. Unfortunately, during this time he was also developing an addiction to amphetamines and alcohol, and an eye for the attractive, "sassy" women he'd meet on the road. Around this time, he also met and began a flirtation with June Carter, who would become his second wife.

His time on the road made his time at home difficult to bear. "It got to where it was like somebody else was coming home, not my daddy," his eldest daughter Rosanne said. "The drugs were at work. He'd stay up all night. He and my mom would fight. It was so sad." According to another of his daughters, Cindy, Vivian would often put her children in the car and go looking for a drunken Cash around town. She finally filed for divorce in 1966; it was granted the next year.

The singer was connected to a huge wildfire in 1965

Johnny Cash had a camper he named "Jesse," and in late June 1965, he and his nephew Damon Fielder took "Jesse" up to Los Padres National Forest for some camping and fishing. Cash, who was at the wheel, spent the drive popping pills, drinking whiskey and swerving. According to an account in Robert Hilburn's biography of Cash, Damon was so irritated with his uncle that he refused to fish in the same spot as Cash once they had parked and set up the camper. What happened next is fodder for debate: Cash said oil from a cracked bearing dripped on a hot wheel, which set fire to grass under his truck; Damon thought an inebriated Cash had spent a book of matches starting a fire to get warm. Regardless, an uncontrollable fire raged around them, requiring the deployment of a rescue helicopter to extract them from the forest. The fire would eventually burn more than 500 acres across three mountains and chase away 49 of the 53 endangered condors residing in a refuge in on the land.

The federal government sued Cash, who was belligerent in depositions. According to Hilburn's biography, he was asked whether he had started the fire, and he replied, "No. My truck did, and it's dead, so you can't question it." When asked about the condors that had fled their refuge, Cash responded, "I don't care about your ... yellow buzzards." Cash was fined $125,000 for the offense.

Johnny Cash was arrested multiple times and spent time in jail

The man who sang so convincingly about shooting a man in Reno "just to watch him die," as he did in "Folsom Prison Blues," was never once in his life incarcerated in a prison. He was, however, arrested several times, for offenses usually related to drugs — either for procuring them or for his escapades while under their influence. Steve Turner's Cash biography tells the story of October 1965, when Cash took a flight to El Paso, Texas, then caught a cab to take him across the Mexican border to Juarez, where he bought 668 Dexadrine and 475 Equanil tablets on the black market and hid them in his guitar. Unfortunately for him, the dealer was under surveillance for allegedly selling heroin; Cash was arrested at the airport, and held overnight on drug smuggling charges. He also faced charges in El Paso for possession of the pills.

Earlier that year, in May, he was drunk and out well past curfew in Starkville, Mississippi when police arrested him and put him in a holding cell overnight to sober up. According to Rolling Stone, Cash kicked his foot against his cell door so hard that he broke one of his toes. Then, in Lafayette, Georgia in November 1967, under the influence of pills, Cash took a Cadillac Eldorado on a joyride through a forest before banging on the door of a rural home until police were summoned. His arrest once again netted him a night in jail.

Did time in a dark cave lead to an epiphany?

Johnny Cash told a story about a time he was in the throes of such drug-related despair that he found himself robbed of the will to live. He said he trekked up to Nickajack Cave, just north of Chattanooga, in the fall of 1967. Nickajack, he said, contained the remains of many cave explorers, "amateur adventurers who'd lost their lives in the caves over the years, usually by losing their way, and it was my hope and intention to join their company." Cash said he crawled through the cave for several hours until his flashlight batteries gave out, at which point, he lay down in the pitch dark, ready to die. He said he'd never felt so far from God — but as he lay there, an epiphany came over him that perhaps it wasn't his time to die. He got up and found his way out of the cave in the dark, guided by a small draft of air, and emerged promising to quit drugs that very day.

Cash recounted these events many times — it's published in his memoir and in magazines and books that cover his life. But the story has many detractors. Marshall Grant, Cash's friend and former bass player, says it never happened. And Robert Hilburn, Cash's biographer, notes that the Nickajack Cave was underwater in the fall of 1967; the Army Corps of Engineers had dammed it up. Also, he wrote, "Cash did not quit drugs that day."

He received a serious diagnosis

By 1997, Johnny Cash had begun stumbling, onstage and off, appearing rigid and unsteady. His daughter Cindy, who was touring with him, remembered, "Every night ... was a prayer: 'Please just let him get through this song.'" He had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease earlier that year, but his off-kilter manner was something different. A week later, the diagnosis changed to multiple system atrophy, also known as Shy-Drager syndrome — a rare degenerative neurological disorder affecting involuntary functions, including muscle control and breathing. He was told he had 18 months to live. While dealing with that news, Cash came down with double pneumonia and blood poisoning, and was in a coma for 10 days. At some point in his recovery, he learned that even the Shy-Drager diagnosis had been wrong; he had autonomic neuropathy associated with diabetes. His touring days were over.

After he recovered his strength and a bit of stamina, he went back to work. Even if he couldn't physically handle long tours anymore, he could still play the occasional show, and he could still record. It was the latter that gained him the most attention in his later years, as he teamed up with producer Rick Rubin for his American Recordings series of albums. His weathered voice sounded vulnerable as he tackled material such as U2's "One," Tom Petty's "I Won't Back Down," and Nine Inch Nails' "Hurt," the last of which earned him a Grammy Award.

Johnny Cash's wife June Carter died

In April 2003, June Carter Cash had been diagnosed with a leaky heart valve and, after a battery of tests, doctors determined that valve replacement surgery was the only option to fix her problem and prolong her life. According to Steve Turner's biography of her husband, she initially balked, saying at 73, she was too old. Johnny Cash begged her to have the surgery; he wasn't ready yet for her to leave him. She had the surgery on May 7, but early the next morning went into cardiac arrest. It took doctors 20 minutes to resuscitate her, after which they put her on life support.

Three days later, doctors performed more tests to see if she responded to stimuli — an indicator of whether she had any brain function. No one was certain how long her brain had been deprived of oxygen during the cardiac episode and resuscitation efforts. "The news," Turner wrote in his book, "was as bad as it could be." Johnny Cash gave permission for life support to be switched off; June's bodily functions were expected to shut down over the course of three or so hours. Instead, she lingered for three days. On May 15, with her family standing vigil around her bed, June Carter Cash died.

Johnny Cash died in 2003

Within four months of his wife June's death, Johnny Cash would also be gone, but not before doing one last bit of work. In the days immediately following June's funeral, Cash reflected on his wife's life and their time together — 35 years of marriage, with very little of that spent apart. He also saw the benefits of keeping busy; mere days after June's funeral, Cash was back in the recording studio with Rick Rubin, adding to the trove of songs the two had stockpiled for the American Recordings series. His ill health continued, though. In his final weeks, he would be hospitalized with pancreatitis. Two weeks after leaving the hospital, Johnny Cash died of respiratory failure stemming from complications from diabetes on September 12, 2003 (via The Tennessean). He was 71 years old.

Cash's legacy as a singer, songwriter, song interpreter, and shaper and re-shaper of country music is unquestioned. There are few figures in country whose shadow looms as long as Cash's; when he was alive, he was larger than life. That status came at a cost — his problems loomed large as well, and as he suffered, so did those around him, those who loved him, and those whom he loved. But when Johnny Cash spoke, millions listened; when he sang, millions sang along; when he died, millions mourned him. That kid who grew up poor on the cotton farm sure made an impact.