Weird Things About Pocahontas You Didn't Know

Pretty much everyone who grew up in the '90s knows who Pocahontas is. Disney Princess, love interest of the great explorer John Smith, all-around example of Native American nobleness. Yes, Disney taught us many things about the Powhatan heroine, and they're all wrong. Mostly.

It's hard to admit that a beloved legend is based on lies, but Disney is pretty good at making people believe stuff that isn't true. After all, they managed to convince a whole generation of little girls that freezing your butt off in an ice castle all by yourself would be the best thing ever.

Disney took a lot of flak for Pocahontas, and it's easy to see why. The Disney Pocahontas was pretty much a symbol of romanticized colonialism and the triumph of civilization over savagery, neither of which is a really great thing to be pounding into the heads of impressionable little girls. So behold, the truth about Pocahontas.

'Pocahontas' was a nickname

The name we know her by is not her real name. In fact her real name is so unknown that if you heard it you wouldn't associate it with anyone because for some reason "Pocahontas," which was a childhood nickname, is the only name that stuck.

According to Biography, the woman we know as Pocahontas had two other names: In private she was called Matoaka, and in public she was known as Amonute. Depending on who you ask, the nickname Pocahontas either means "little playful one" or "laughing and joyous one," or possibly "little wanton" or "spoiled brat," implying that she was kind of undisciplined and maybe even a little mouthy.

The fact that her nickname is the one that went down in history tells us something about her personality. She was fun-loving and a little rebellious, which are qualities we (mostly) like in modern kids but that didn't tend to be qualities 17th-century Europeans admired in girls. On the other hand, Pocahontas was known to be her father's favorite child, so clearly the Powhatan didn't have the same expectations for well-behaved young ladies as their European neighbors did.

She had dozens of siblings

Pocahontas was the daughter of Chief Wahunsenaca, also called Chief Powhatan. The chief had a buttload of wives, which means he also had a buttload of other kids. According to the Encyclopedia Virginia, in the Powhatan tradition, the chief got to keep each wife until she had a child, and then he sent her back to where she came from and supported her and her offspring from afar. (It's actually pretty similar to what a lot modern politicians do, minus the marriage.) At the age of 8 or 10, the child would move back to the Powhatan capital and Mom got to remarry, which means Powhatan women only tended to have a couple of kids while the men might have dozens.

So Pocahontas had loads of half-siblings but no full siblings. By the time she was 10 her father was around 60 years old, so she was one of the youngest of his offspring. If you grew up in a large family you already know how hard it is to actually get your parents' attention, so imagine if you were competing against 20 or 30 other kids. It's no wonder Pocahontas thought she had to be mouthy and undisciplined.

Sorry Disney, she wasn't really a princess

Everyone knows Pocahontas belongs in that most sacred of lineups, right next to Snow White and a couple doors down from Ariel. Pocahontas was a princess, or so sayeth the great and powerful Disney.

Apologies, but no. Pocahontas wasn't a princess, and not just because she didn't wear a crown or live in a castle. According to Biography, the Powhatan were a matrilineal society, so her father's status as the chief basically meant nothing as far as his daughter was concerned. Instead, it was her mother's status that mattered — if her mother had been born into a "chiefly clan," then Pocahontas might have been something like a princess, although the European royalty structures aren't very applicable to Native American people. But alas, Pocahontas' mother isn't even remembered, which likely means she wasn't a person of importance as far as her people were concerned. Sorry, Disney, you got it wrong. But if it's any consolation, so did everyone else.

Saved you from what? All the feasting?

The explorer John Smith famously told everyone who would listen that Pocahontas had saved his life. In 1624, which was 17 years after he met Pocahontas and seven years after her death, he wrote in The Generall Historie of Virginia that "Pocahontas the king's dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save him from death." Now, according to the Encyclopedia Virginia, the problem with this story is that Pocahontas was like 11 years old at the time and certainly wouldn't have been included in that initial meeting between Smith and her father, in fact since there was a big feast planned in Smith's honor she was probably helping with the preparations. It's also pretty doubtful that anything remotely violent even happened at that meeting, since you wouldn't really be preparing a feast to honor someone whose brains you'd just scattered all over the place. Smith himself discounts his own story in a letter he wrote a few months after the meeting, in which he made no mention of being threatened, unless it was by difficult interview questions or too much venison.

So why did he later say he'd been attacked by the Powhatan and subsequently saved by Pocahontas? Probably because heroism and mortal peril sell more books than tough interview questions and overstuffed stomachs.

But what about the romance?

In the 1995 animated film Pocahontas, Disney created a color-coordinated but seriously gross romanticism of American colonialism and the "noble savage," and then basically made everyone believe the historical Pocahontas had been romantically involved with John Smith. Remember that Pocahontas was just 11 years old when Smith first came to the Powhatan — and according to Indian Country Today, Smith was 27. So a romance would not only have been morally reprehensible but unlikely in pretty much every other way — Powhatan children were protected by the whole village, and Pocahontas certainly wouldn't have been allowed to associate privately with a strange white dude.

That's also a good argument against the legend that has Pocahontas defying her father to bring food and supplies to Smith and the other settlers. It was a long journey to Jamestown, and to get there you had to travel quite a ways with a 400-pound canoe. That wasn't something Pocahontas would have been able to pull off alone, even if she'd been able to sneak out of the village without anyone noticing.

Thanks for the food, sorry about the kidnapping

The Powhatan did give food to the English, but they did it officially — the early settlers were hopeless at farming and the Powhatan figured it would be neighborly to help them out. Pocahontas became a sort of link between the two peoples because she was usually sent along with the envoys of food.

Then came the winter of 1608 to 1609, which was particularly dry, and the Powhatan didn't have a whole lot of food to spare anymore. According to the National Park Service, trade negotiations were starting to get a little uncomfortable, so uncomfortable that the chief allegedly decided he'd had enough of Smith and started making plans to have him killed. But thankfully Pocahontas ran through the woods one night with a warning and Smith was saved — yes, yet another story about Pocahontas selflessly protecting the intrepid explorer because we're all totally not bored of the first one. Again, the story is probably false since Pocahontas was a child and very much under adult supervision, so the idea that she'd run off alone at night is not very credible.

Anyway, at this point Pocahontas was important enough that the English started dreaming up evil plans, but were evidently so sloppy about it that the Powhatan knew something was up. So Pocahontas' coming-of-age ceremony and her marriage to a Patawomeck warrior named Kocoum were mostly done in secret for fear the English would intervene and abduct her.

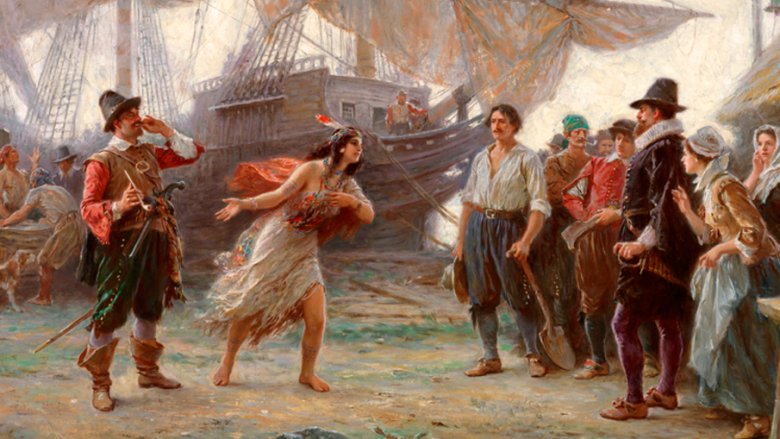

Heck with it, let's just abduct the chief's daughter

After that, Pocahontas should have lived happily ever after. But she was a native woman living in 17th-century America, so no. The Powhatan were right to suspect that the English were planning to abduct her because they did, and just to make it all so much more insulting it was her husband's people who basically sold her to the enemy.

While she was in captivity, the English engaged in pretty standard mental torture techniques, including repeatedly telling Pocahontas that her father didn't really love her and didn't care if he got her back, and pressuring her into adopting European customs and European religion. While she was in captivity she met tobacco farmer John Rolfe, and the circumstances of their marriage aren't really clear. Regardless, they married, their union resulted in a child, and she converted to Christianity and changed her name to Rebecca.

According to ThoughtCo, Rolfe claimed to love Pocahontas, but his declarations of love were seriously gross. He described his bride as "one whose education hath been rude, her manners barbarous, her generation accursed, and so discrepant in all nutritive from myself." Ah, young, bigoted, paternalistic love.

Wining and dining, entertainment and dysentery

After her wedding Pocahontas went to England, but not because Rolfe wanted her to see his homeland and meet the in-laws or anything. According to the Powhatan Nation, the trip was basically a propaganda campaign to help raise funds for the Virginia Company.

Pocahontas arrived in London in 1616, and was introduced to "English society" — she met with the bishop of London and King James I, was invited to the theater and was basically paraded around like an exotic pet until the rich white people got bored of her and sent her off to live in a village outside London. At some point Pocahontas and her husband decided to return to Virginia, but she got sick shortly after boarding the ship. She disembarked at Gravesend and died at the age of 21.

It's hard to say what killed her — Native Americans were particularly susceptible to European diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis, but some speculate she might have been poisoned. At least one oral history says she became ill shortly after eating dinner aboard the ship, and that she died soon afterward.

But why would anyone kill Pocahontas? Maybe she knew too much about English plans to take down the Powhatan nation, and conspirators feared she would return to her own people and wreck everything. Or maybe she really did just die from dysentery. Like so many other things, we may never really know the truth.

Pocahontas evidently has millions of descendants

Some accounts of Pocahontas' life say she had a child with her first husband, and others say she only had one child — Thomas Rolfe, who was born shortly after her marriage to John Rolfe. Because the fate of her first child — if he/she actually existed — isn't really known, genealogists only have Thomas Rolfe to obsess over.

According to the Encyclopedia Virginia, In the 1920s, some lovely people dug up the bones of everyone buried at St. George's Church in hopes that Pocahontas could be identified, but alas. In retrospect, it was probably a good thing that her bones weren't found, because DNA evidence would have almost certainly shattered the fantasies of millions of people who aren't really descended from Pocahontas but wish they were.

Pocahontas does not have as many descendants as claim to be in her family tree. Her son Thomas was never a part of Virginia's elite, and he died in 1681, in a place where there weren't really good records of births, marriages, and deaths. So while it's true that he did have an unknown number of children, no one ever put him in a family tree until the 1820s, more than a century after his death. Which means all those people claiming descent are mostly doing so based on family legend rather than real documentation.

The Pocahontas Clause

One final note, just in case you aren't already feeling a little unsettled by all the colonialism and latent racism — being descended from Pocahontas is kind of a status symbol. People like to brag about it, and also they get really defensive when other people call their claims into question. Even in the early 20th century it was such a popular thing to claim descent from Virginia's most famous Powhatan that some really nauseating stuff was actually written into law so people could feel good about being descended from Pocahontas but also feel good about being white.

According to the Encyclopedia Virginia, in 1924, the Virginia General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act, which was basically just meant to keep white people labeled white and black people labeled black and everyone else fit neatly into their own pure little racial category. But those claiming descent from Pocahontas were really not cool with this, and not because of the obvious disgusting nature of such a law but because they were afraid they wouldn't be considered white if they continued to brag about their famous ancestor. So to appease them, an exception was made: If a person was 1/16th Native American but remained untainted by the blood of any other non-Caucasian, they were still considered white. What a relief!

Anyway, the clause came to be known as the "Pocahontas Clause," and everyone lived happily ever after, right?