Wilma Montesi: The Mysterious Italian Murder Of The 1950s

In 1950s Italy, a seemingly innocent 21-year-old woman named Wilma Montesi washed up dead on a beach miles from home. The beautiful young girl stoles people's hearts and the odd circumstances around her death captured their imaginations. So fascinated was the public by the Montesi case, that similar to the Madeleine McCann case today, a press circus formed that would last for many years. The story also caught the eye of one of Italy's best directors, inspiring the movie masterpiece "La Dolce Vita."

Although the police originally ruled that Montesi's death was an accident, so many lurid rumors arose in the papers about the dead girl that the case was reopened and a string of suspects were charged. It was later alleged that Montesi was no innocent at all — but had got mixed up in a dark criminal underworld connected to powerful aristocrats and politicians.

While nothing was ever really proven about Montesi's death, curious details that emerged from the case continue to fascinate cold case fans worldwide. On the other hand, many people have argued that all Montesi's death really proved is that the media is willing to sell lies in order to sell newspapers.

The body

Wilma Montesi, a seemingly ordinary girl from a working-class family in Rome, left her house around 5:15 pm on the evening of April 9, 1953, passing by the concierge into the streets of the Via Tagliamento district in Rome, where she lived with her family. Her mother and sister had gone to see a movie together that afternoon and she had declined to join them.

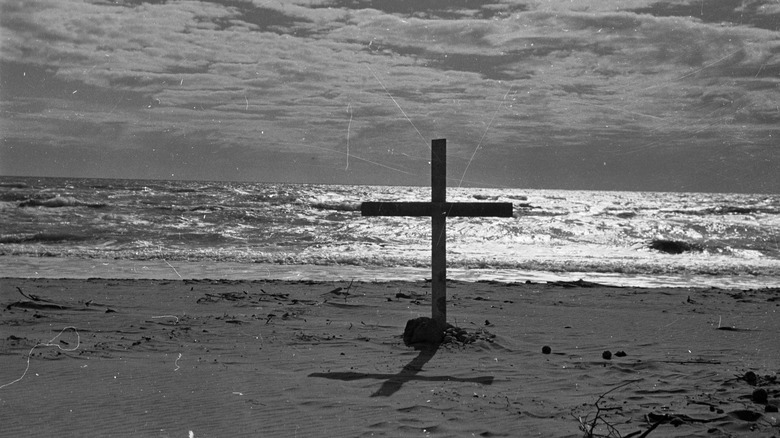

Montesi had mentioned that she might go for a walk that afternoon but she did not return home that day. Around 36 hours later, her body was discovered miles away on a beach in the Tovaianica fishing village on the coast. Montesi appeared to have drowned but there was no obvious explanation as to how. The perplexing circumstances around her death would create a media circus in Italy that has scarcely been equaled.

Not only had Montesi had no real reason to be in the area in which she was found, but she had not taken any money or jewelry with her, and her identity card was left abandoned at home. Even more bizarrely, she was fully clothed from the waist up, but her skirt, shoes, stockings, and garter belt had been removed. The autopsy concluded that there was no evidence of a sex crime, and Montesi was still a virgin when she died.

The questionable autopsy report

The original autopsy report ruled that Montesi had probably died by accident. According to Wayland Kennet's "The Montesi Scandal," a witness told police she had seen the young woman on a train to Ostia — Rome's ancient port on the coast — at around 5:30 pm. The police concluded Montesi had gone paddling by the seaside and had fallen in. Years later, The New York Times reported that the Montesi family still believed that this was the case — they claimed, Montesi was a well-behaved young woman, unlikely to have been involved in anything unusually sordid, her death was simply a random tragedy.

Because Montesi had a chilblain on her heel, the official story ran that she had gone to the coast to soothe the sore with salt water. It was concluded that having gone to bathe her feet she had then experienced a fainting spell (she'd had a few before) and tragically drowned. Just 21 years old, beautiful, cheerful, and engaged to be married — suicide seemed unlikely but couldn't be ruled out.

But not everybody explained this elaborate explanation. There were some strange things about Montesi's death that raised eyebrows and her fiance and many members of the press did not buy that it was an accident. Why had the young woman removed her garter belt just to soak her feet? Was there something suspicious about how far her body drifted down the coast? And why had a witness come forward to report he had seen a girl who looked just like Montesi in the area when she disappeared, sitting with an unidentified man in an Alfa Romeo 1900?

The drug ring and the mysterious estate

Before long journalists began proffering alternative explanations for Wilma Montesi's demise. The most shocking claims of all came from reporter Silvano Muto, who wrote in the Italian magazine "Attua-Litta," that Montesi had gotten embroiled in a dark underworld of drugs and sex parties that ultimately led to her death.

According to Stephen Gundle, in his book "Death and the Dolce Vita," Muto was originally tracking the source of Rome's booming drug trade when he followed various leads to the coast around Ostia. Several bodies tenuously connected to the drug trade, had already turned up in the area long before Montesi died. During the course of his investigation, he met an informant who claimed she had met Montesi at a sex party in the area.

Muto claimed that Montesi had been involved in the drug ring operating on the coast, that she was one of many girls responsible for transporting the product on behalf of the dealers, and that one night, she had died by accident, having taken too much opium. Although in the original piece, Muto did not name his sources or the criminals involved, it was later revealed that the alleged ring revolved around the mysterious Capocotta hunting lodge on the coast near Rome, a place connected to many members of Italy's elite. The pope himself and a host of other dignitaries were members of the St. Hugo's club that ran out of the lodge, and rumors spread that it was the site of shady activities and wild sex parties. The mysterious Alfa Romeo 1900, Muto alleged, took Montesi out there regularly.

The shady marquess

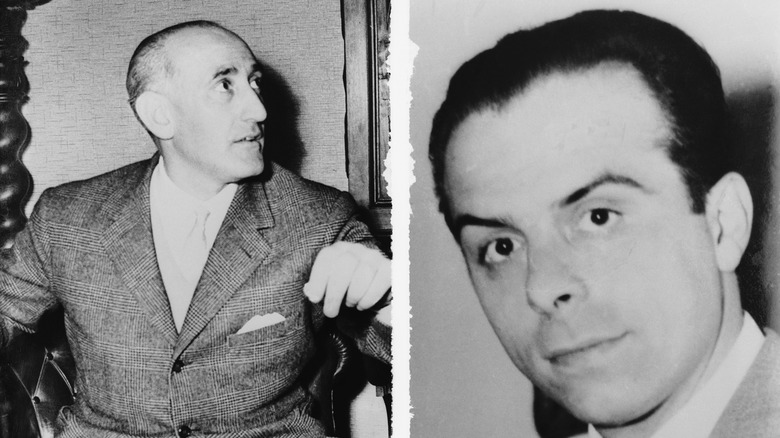

Journalist Silvano Muto's wild claims soon got him arrested on the grounds he may have been printing lies. However, when he came to stand trial, Muto was able to martial some stunning evidence that caused a scandal. At the trial, Muto named the owner of the Capocotta estate, the Marquess Ugo Montagana as the leader of the drug ring that had accidentally killed Montesi.

Whether or not he was a drug dealer, the marquess proved to be an extremely shady character. It came to light that the Carabinieri (an Italian law enforcement agency) had filed a report on Montagana for committing a string of fraud offenses, including cashing bad checks and filing questionable tax returns. Stephen Gundle's "Death and the Dolce Vita," records that Montagna had also made at least some of his wealth by pimping out beautiful women to wealthy Italians.

Before he was due to stand trial, Muto's article caught the attention of Montagana's ex-lover, Anna Maria Montana Caglio. Caglio confirmed Muto's story, saying she had suspicions that Mantagana was involved in the murder and that he spent a great deal of time with Piero Piccioni — another rumored suspect who had been accused in the press. According to Time, Caglio claimed that she was berated by Montagana when she brought up the subject of Montesi, "Ugo became simply furious and told me I knew too much, and I had better go away." She followed up that "Montagna told me he had to go to the chief of police to hush up the affair since they were trying to link Piero Piccioni with the death of Wilma Montesi."

A politician's son is dragged through the mud

Piero Piccioni, the son of a prominent politician, the government's foreign minister also became the subject of wild press speculation. A rumor spread in the press that Wilma Montesi's missing garter belt had been handed into a police station by Piccioni and promptly destroyed in a hasty cover-up. Originally, to avoid a lawsuit Piccioni wasn't named directly — because Piccioni means "pigeon" in Italian, a newspaper simply made a wry reference to "carrier pigeons" in an article about the belt. Soon however he was named directly and the Piccionis scrambled to control the damage. Piero's dad, Attilio Piccioni even offered to resign from the government although he was ultimately told to remain in his post.

Whether he was guilty or not, the young Piccioni made for an easy target. A wealthy jazz musician and composer, he lived the life of a playboy, perfect material for newspapers interested in vice. It is also plausible that the rumor was purely politically motivated and had no real truth to it.

The crisis deepened when informant Anna Caglio identified Piccioni as a close associate of the dastardly Marquess and possible drug lord Ugo Montagna. Although many people viewed the charges against Piccioni as ludicrous, Caglio did a great deal of damage by naming Piccioni as Montagna's "assassin," painting him as an integral part of his supposed drug ring.

A Prince is implicated

But what about the mysterious Alfa Romeo 1900 which Wilma Montesi was supposedly seen in shortly before she died? To the surprise of all, the car was eventually traced back to a real-life royal, the grandson of Victor Emmanual III, Prince Maurice of Hesse.

After being summoned by the police, Maurice confessed he had been to the now infamous Capocotta estate around the time Montesi was killed. He also admitted he had been in the company of a mysterious woman he would not name. As a royal, Maurice technically had privileges at the hunting lodge, despite it being owned by Ugo Montagna (via Stephen Gundle, "Death and the Dolce Vita"). Despite his prestigious background, Maurice was one of several people who had their passports taken away, while investigations limped on.

When the case eventually went to trial the Prince was able to produce a witness who claimed to be the woman in the vehicle. Assuming his story was true, Maurice had withheld the identity of his companion as a gentlemanly measure to protect her. One of the gatekeepers at the estate confirmed the Prince's story, and he ultimately was absolved.

Was there a police cover-up?

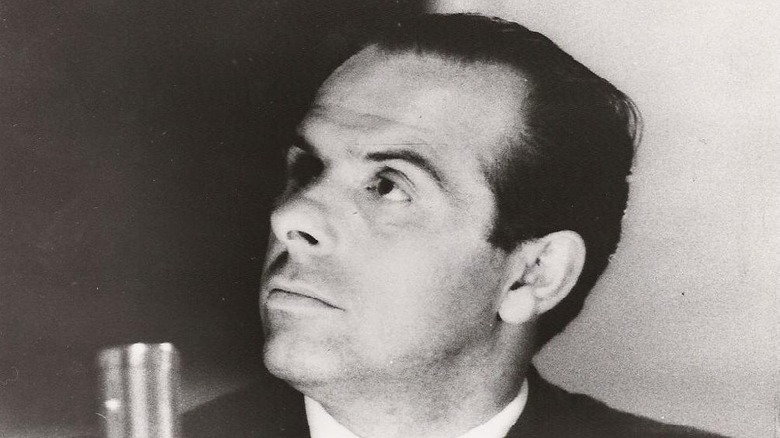

Some of the most serious accusations to come out of the Wilma Montesi case involved suggestions of a police cover-up. The head of the Roman Police, Saverio Polito, was heavily scrutinized and held responsible for the widely disbelieved original ruling that Montesi had died by accident. The assumption was made that Polito was protecting the rich and powerful in some way, but the ensuing uproar nonetheless caused him to double down on the original explanation. In an ill-advised move, he delivered a press release, attacking the newspapers for speculating about "the son of political personality," a comment that did nothing to quell rumors that the police were protecting the powers that be (per Stephen Gundle, "Death and Dolce Vita"). At the age of 73, Polito was placed under house arrest before standing trial for his possible involvement in the crime.

Police chief Tomasso Pavone was also implicated in the affair. At the trial of Silvano Muto, Anna Caglio had testified in court that Pavone had been given an apartment by the criminal marquess, Ugo Montagna, and had helped to cover up the murder. Although he denied there was any conspiracy, the Montesi case forced Pavone to resign from the force in 1954 and he did later admit in court that he spent a good deal of time liaising with the dubious marquess.

The Venice Trial

In 1957, the key suspects — musician Piero Piccioni, police chief Saverio Polito, and Marquess Ugo Montagna — were sent to trial in a massive court case in Venice. Stephen Gundle, in "Death and the Dolce Vita" notes that there was so much excitement about the trial, everyone involved from the defendants to the witnesses was harassed by flocks of journalists, and scores of reporters showed up in Venice to write about the event. However, hopes that a grand conspiracy would be revealed, were dashed.

The people who really wound up on trial were not the accused. Instead Anna Caglio — whose stories had helped co-create the conspiracies about Montesi's death — and Montesi's suspicious playboy uncle, Giuseppe Montesi — were put through the wringer. Caglio was derided as a fantasist and a loose woman by her ex-lover, and ultimately, her story proved to be easy to pull apart; nothing she said at trial proved conclusively that any of the suspects were in any way involved in Montesi's death.

Montesi's uncle Giuseppe Montesi on the other hand was also painted as an unpleasant character — a notorious womanizer despite being engaged. At the trial, it was revealed Montesi's mother had lied about the fact Giuseppe often went out alone with his niece. The fact that Giuseppe had disposed of his car a month after Montesi was killed — added to the lurid insinuations. Drawing attention away from the accused, the prosecution implied that Giuseppe was the real killer all along and the press began to agree with them.

Case dismissed

Ultimately, the Venice trial led nowhere and the three main suspects were acquitted. Instead, Anna Caglio and Silvano Muto were found guilty of defamation, and many people assumed that the charges against Piero Piccioni had been political after all. No drug-ring revelations were confirmed and it all seemed like a disappointing end to the gossip — had the entire conspiracy been concocted by fame-hunters and spun to sell newspapers?

Some people concluded as much, however, doubts about the handling of the case have persisted to some degree. The Wilma Montesi scandal had produced tantalizing rumors of a seedy world in which wealthy men had the ear of the police. The Marquess Ugo Montagna was undeniably an unsavory figure and Piero Piccioni in particular told numerous lies during the scandal and at the trial (per Stephen Gundle, "Death and the Dolce Vita"). Piccioni's alibi had been anything but watertight and he had lied about knowing Marquess Ugo Montagna, a man with whom he did prove to have a very cozy relationship.

The tragedy inspired film classic La Dolce Vita

The Wilma Montesi scandal is said to have inspired one of Italy's greatest directors, Frederico Fellini, who made reference to the affair in his masterpiece "La Dolce Vita." Marcello, the film's protagonist, is a gossip columnist who takes the viewer on a grand tour of Rome, exposing its shallowest creatures. In probably the film's most famous scene, a glamorous starlet wades provocatively in the Trevi Fountain.

Stephen Gundle in "Death and the Dolce Vita" writes that the film's satirical examination of modern Italy — a world entranced by money, fame, phony religion, and sex — caused outrage upon first release. It was this same vapid world that the Montesi scandal had exposed — shedding a light on the world of the rich and powerful and generating enormous publicity through selling seedy stories to tabloid readers who couldn't get enough of the rumor mill. Like the movie's hero, ordinary Italians were both repulsed and entranced by disturbing stories about starlets, politicians, and playboys.

At the climax of "La Dolce Vita," a gruesome sea monster washes up on a beach, a creepy return to earth after several hours of glitzy images. Gundle connected this dark reference to Montesi's demise, noting that originally the script had included extended sections at the fishing village of Torvaianica where the young girl's body was found.

The case has been connected to the birth of the Paparazzi and press freedom

The Wilma Montesi debacle has been categorized as a landmark case for the press in Italy. Stephen Gundle, whose work "Death and the Dolce Vita" is the most definitive account of the scandal, connected the entire affair with the rise of the Paparazzi in Italy and with press freedom. In fact, the word "Paparazzo" was coined around this time by Frederico Fellini himself, who gave the name to one of the characters in the Montesi-inspired "La Dolce Vita."

The one positive of the drama that unfolded was that it showed that the press was now able to challenge the authorities. Due to their dogged investigations — the questionable police report on Montesi's death was held up to scrutiny, and the case was officially reopened by the procurator general despite police objections. This was a big sea-change for Italy which had only been free from fascism and press censorship for a few years.

On the other hand, it was also the beginning of the rise of a new kind of invasive journalism, one that relies on rumors and deprives its victims of privacy. Wilma Montesi's grieving family was disturbed by the endless stories that were trotted out to slake the public's interest. Reputations were smeared, including that of the dead girl — and in the end, even if Montesi was murdered, no concrete truths were uncovered.