David Bowie's Tragic Real-Life Story

David Bowie was an icon in music and pop culture, a chameleon who changed personas as they occurred to him and as they helped him express himself creatively. He flouted a fluid sexuality, an expression of freedom that made everyone take note, and compelled his fans to likewise feel free to make their own statements on who they were and what they stood for. He flabbergasted and enraged some less flexible folks, fanning the flames when he made it clear their disapproval mattered not one bit to him.

Bowie was, however, a complex and complicated man, having grown up under the shadow of mental illness, a "family curse" that would one day claim his beloved brother. Bowie's own self-inflicted pain came courtesy of drug addiction, and the twin specters of schizophrenia and a reliance on cocaine merged into an affliction that could have taken him long before he was ready to leave this world, long before his admirers were ready to lose him. As it stood, his later years were marked by illness, interrupting the peace he had found in his work and with his family. This is the tragic, real-life story of David Bowie.

Mental health issues haunted his family

David Bowie's mother Peggy Jones (née Burns) was born into a family touched by mental illness, and she herself may have fallen victim to some degree. Marc Spitz, one of Bowie's biographers, noted that schizophrenia was a "family curse" that "seemed to be seared deeply into the genetic code." The behaviors associated with schizophrenia can recess from outside view, only to be triggered by some calamity. For Peggy and her siblings, there were two such forces — their mother, Margaret, and the Nazis' bombing of England during World War II. According to one account, Margaret Burns "was a cruel woman who took her anger out on everyone around her." Margaret's own daughter, Peggy's sister Pat, once said her mother "was a cold woman. There was not a lot of love around."

Two of Peggy's other sisters, Nora and Vivienne, had begun exhibiting signs of schizophrenia early in their lives, but the nightly shelling during the Blitz in 1940 (coupled with the idea of Hitler occupying England) exacerbated the girls' problems. Bowie himself wondered whether he would also fall victim to schizophrenia one day. Some even theorize that he developed so many personas throughout his career as a way of dealing with some latent schizophrenic tendencies.

His half-brother had similar demons

David Bowie's half-brother Terry was born out of wedlock and, due to the stigma associated with such births, was handed off to his grandmother, Margaret, who was emotionally and physically abusive to the boy. His mental instability had its genesis then, and grew over time, even when, at 9 years old, he was sent back to live with his mother, her new husband, and his baby half-brother, David. From that point, David looked up to Terry, and there was genuine affection between the two. Terry struggled with his mental illness but eventually was able to join the Royal Air Force, leaving his family for a time.

When he returned from the service, Terry spent time with David. One night they went to see Cream at a club in London, but the volume of the music proved to be too much for Terry. David took him outside, and Terry had a schizophrenic vision — he saw the ground opening up and fire coming out of it, and told David he had such visions often. After David's father died two years later, Terry spent time in and out of mental hospitals for years until he committed suicide in 1986. Several potent Bowie songs, from "All You Pretty Things" to "Jump, They Say," are said to contain recollections of Terry — of his visions and of him as a man, as David's big brother.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

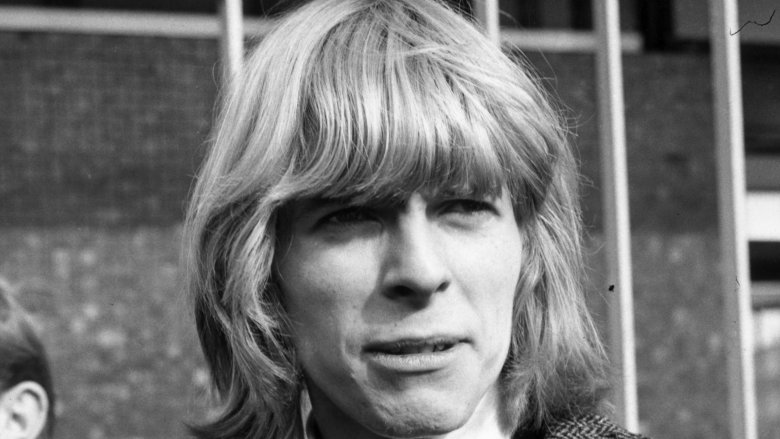

He was nearly blinded in a fight over a girl

In his adolescence, David Bowie's best friend was George Underwood. They hung out together, played music together, and, in one famous moment, even fancied the same girl. According to Bowie biographer Marc Spitz, Underwood had managed to get a date with this girl, but on the day of the date, Bowie convinced him that the young lady had had to cancel. As she had done no such thing, she was left waiting for over an hour before giving up and going home. When Underwood found out, he found Bowie and punched him in the left eye, inadvertently scratching Bowie's eye with a fingernail in the process.

After it was determined that the eye had sustained an injury mere cold compresses could not cure, Bowie was sent to the hospital. According to one account, doctors noted the muscles in the eye were damaged. He could still see (and would not lose the eye, which was a concern initially), but for the remainder of his life his left pupil would be permanently dilated — a condition called anisocoria. Underwood felt guilty for quite a while afterward, but the injury left Bowie with what he termed "a kind of mystique," perhaps best seen on such Bowie visuals as the album cover for "Heroes" and the close-ups in his "Valentine's Day" video, above.

His gender fluidity might have been illegal

When David Bowie died in 2016, many gay, bisexual, and transgender fans and performers paid their respects, often noting his influence in their lives and in quasi-mainstream queer culture, particularly in the '70s. Then, in his Ziggy Stardust and Thin White Duke personas, Bowie played with androgyny and sexuality as few performers of his stature had previously. He was often asked how he defined himself in terms of his sexuality, and he often gave coy responses. He did come out as gay in 1972, as bisexual in 1976, and finally as a "closet heterosexual" in 1993. No label, however, could truly define him.

While his fans applauded his gender fluidity and abstract sexuality, not everyone applauded. British law, in particular, had long seen homosexuality as an affront. In the 1800s, it was even punishable by death. Although Parliament passed the Sexual Offences Act in 1967, which partially decriminalized male homosexuality by allowing consensual acts in private between men aged 21 and older, anything outside of the scope of "private" would still be considered illegal. So when Bowie came out in 1972, he was at least admitting to having previously engaged in illegal acts. His flamboyance was a direct parallel to that of writer Oscar Wilde, who, according to writer Bill Wyman, "had been imprisoned and had his life destroyed for being gay." Bowie might have been born at the right time to be able to express himself and his sexual ambiguity; he also might have been responsible for moving acceptance of it forward.

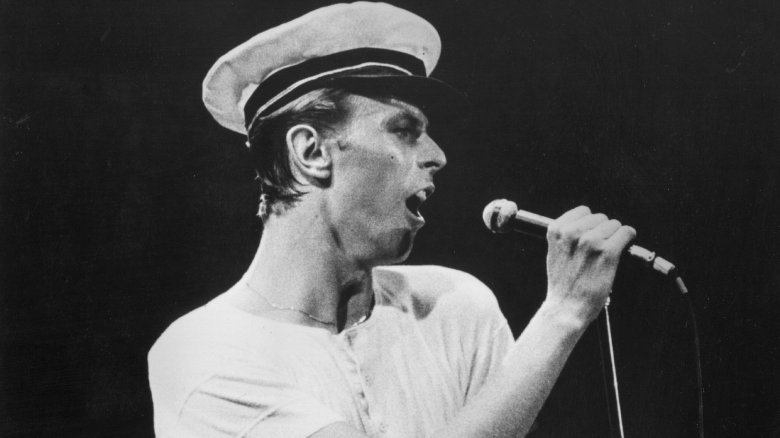

For a time, he had a debilitating cocaine addiction

"Cocaine," Bowie biographer Peter Doggett once mused, "was the fuel of the music industry in the '70s." If that's the case, Bowie was well fueled for much of the decade, to almost crippling effect. Bowie guitarist Carlos Alomar told the New York Post that Bowie used the drug to stay up late into the night, sometimes all night, sometimes for days in a row. "Its function was to keep you alert," he noted, "and that's what [Bowie] was doing. It did not stop his creativity at all." It did occasionally affect his performance onstage. While careful not to appear "out of it" in front of audiences, Bowie would sometimes forget lyrics, according to Alomar. In these instances, Alomar (who was also a background singer) would abandon singing his own parts and sing Bowie's, in order to get Bowie resituated in the song.

What cocaine did do, however, was sink Bowie into mental states akin to the schizophrenia other members of his family had suffered. "He spent a decade trying to avoid what his grandmother called the family curse," Doggett wrote, "and then several more years creating his own form of psychosis with cocaine and amphetamines." So bad was his addiction and the related mental issues while making the film The Man Who Fell to Earth in 1975 that Bowie claimed to see "demons of the future on the battleground of one's emotional plane." Soon after, he moved to Germany to clean up.

He was accused of being pro-fascist

In the mid-'70s, certain aspects of David Bowie's Thin White Duke persona gave fans pause, mostly for what Bowie himself described as the "very Aryan, fascist-type" qualities of the character. In 1976, he told Playboy magazine, "I believe very strongly in fascism. The only way we can speed up the sort of liberalism that's hanging foul in the air at the moment is to speed up the progress of a right-wing, totally dictatorial tyranny and get it over as fast as possible." He also likened Adolf Hitler to rock stars, particularly Mick Jagger, in the way he "worked" his audiences. And then there was the moment he was photographed waving to fans at Victoria Station in London in a manner that resembled a Nazi salute.

Bowie eventually recanted all the fascism talk and admiration for Hitler. His copious consumption of drugs left him, in his own words, "at the end of my tether physically and emotionally and [with] serious doubts about my sanity." In truth, he was exhibiting the symptoms of cocaine psychosis, in which hallucinations and distorted perceptions of reality are sometimes joined by delusions — in Bowie's case, messianic delusions. To escape the cloud that had descended upon him, he did what any great artist would do — he applied himself to his craft, creating three of his finest, most acclaimed records: Low (1977), "Heroes" (1977), and Lodger (1979).

Bowie Bonds wound up being junk

In 1997, David Bowie was convinced that copyright statutes were on their way to extinction and that "authorship and intellectual property [are] in for such a bashing. Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity." With that in mind, he negotiated a deal with record company EMI to release 25 of his records, dating back to 1969, which paid him a 25 percent royalty rate on wholesale sales. Using those royalties as backing, he then worked with financier David Pullman to issue "Bowie Bonds" — securities Bowie used to raise $55 million against revenues from those records. It was a financial innovation that gained Bowie and Pullman headlines.

Other artists like James Brown, Rod Stewart, and the Isley Brothers got into the game, creating similar securities against their own record sales. But finance often operates like a clock — all the wheels, pinions, driving weights, and such must be properly synchronized and in good working order. EMI sustained hundreds of millions of dollars in losses and would eventually be bought up by a private equity firm. By that point, debt issued by EMI had been downgraded to junk status, with Bowie Bonds downgraded to one notch above junk. The bonds liquidated in 2007.

Heart problems sent him out of the spotlight

On June 23, 2004, David Bowie shortened a concert in Prague due to what he thought was a pinched nerve. It wasn't. Two nights later at the Hurricane Festival in Germany, Bowie left the stage after a final encore of "Ziggy Stardust" and collapsed before he could get backstage. He was rushed to the hospital and diagnosed with a blocked artery requiring an immediate angioplasty — an emergency procedure in which surgeons flatten fatty tissue blocking the artery and insert a stent to restore blood flow. He remained in Germany until he was well enough to fly, and within two weeks was back at his home in New York. Neither he nor anyone else knew that the June 25 show would be his last full concert.

He appeared infrequently over the next two years — playing "Life on Mars" and singing with Arcade Fire at the Fashion Rocks benefit in 2005; performing "Comfortably Numb" and "Arnold Layne" with David Gilmour in 2006; playing "Wild Is The Wind" and "Fantastic Voyage" and duetting with Alicia Keys on "Changes" at the Keep A Child Alive benefit in New York later in 2006. Bowie showed up here and there at benefits or fashion shows, but never again as a full-on performer. He disappeared from the spotlight almost completely, until reemerging in 2013 with the album The Next Day, though he would not play onstage or give a single interview to support the record.

He received a daunting diagnosis, got to work

According to Rolling Stone, David Bowie showed up to the first session for his final album, 2016's Blackstar, with no eyebrows or hair on his head. He had been diagnosed with liver cancer and was receiving chemotherapy. He told very few people about it, preferring to keep to himself as he worked toward both beating the disease and creating a musical statement that would outlive him. His physical and emotional states both necessarily found their way into the songs on Blackstar. The album's themes of death and the afterlife seem chilling in retrospect. "Look up, I'm in heaven," he sang on the song "Lazarus" (also the title of a musical he helped create in his final year). "I've got scars that can't be seen." When his producer Tony Visconti figured it all out, he told Bowie, "You canny bastard. You're writing a farewell album."

Bowie did not want word of his condition or of the forthcoming record's existence released to the press, so he had the musicians he worked with sign nondisclosure agreements. Guitarist Earl Slick (who had played with Bowie since 1974) said such a step was unnecessary due to the musicians' admiration of Bowie as an artist and a person. "I didn't have to sign it," Slick told a British talk show. "I signed it because I was asked to. All anybody had to do was to ask to be quiet and out of respect, we would have been."

Cancer took David Bowie, two days after his birthday

On January 10, 2016, two days after his 69th birthday and the release of Blackstar, David Bowie died. The statement from his family shocked everyone, as the cancer diagnosis had been kept so quiet. In the weeks leading up to his passing, he recorded demos for five new songs, amazing his producer Tony Visconti. According to Rolling Stone, just a week before he died, Bowie told Visconti he wanted to make one more album. It never came to be. "He always did what he wanted to do," Visconti wrote. "And he wanted to do it his way and he wanted to do it the best way. His death was no different from his life — a work of art."

With Bowie's death, fans were left to ponder what he'd left behind. He had channeled the tragedies of his mother's family's mental illness and that of his brother into the personas that enabled him to express his unique vision and the sounds that accompanied it. He had transcended the accepted attitudes on sexual identity to influence generations. He overcame a crippling drug addiction to find peace in his life and the creation of his art. Even though he should have had more years to live and create, his final work succinctly closed the book on his life — as rich and unforgettable a life as one could hope to live.