Books Authors Regretted Writing

Few writers can be said to have stumbled into the world of writing books simply by luck or accident. Most would have previously dreamed of seeing their name in print long before they got to that point. And even then, it is no guarantee that working hard at the art of writing and playing the publishing game will lead to a wide readership, fame, and wealth — all of which are the rewards for literary success.

Understandably, an unsuccessful writer may regret that their work never gains the critical acclaim or commercial success that they think it deserves. But even famous and respected authors can come to lament the works they have created, including those that the wider world considers timeless classics. Here are some of the books that famous authors truly came to regret writing, incidents that prove that no matter an author's intentions, you can never guess the impact a book might have on your career, private life, or the wider world.

The Catcher in the Rye

Few books have shaped the American psyche quite like J.D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye," whose rendering of adolescent angst as typified in the story of depressed teenager Holden Caulfield has reverberated down generations. First published in 1951, it has become both a classic and a right of passage for many readers, and it still continues to sell hundreds of thousands of copies a year.

The emotional insight at the heart of "The Catcher in the Rye," as well as the relatable and infectious narration of Caulfield, goes some way to explaining its cult status. So believable is the character that it is in fact easy to conflate the voice of Caulfield with that of Salinger himself, making the writer a mysterious and enigmatic hero to many readers.

But Salinger hated the attention that his most famous work brought to him, and he became a notorious recluse shortly after its publication, rejecting any advances to have the novel adapted for the screen or stage. The legend of the novel exploded in 1980, when it was reportedly one of the items in the possession of John Lennon's murderer, Mark Chapman. Biographers have described Salinger's deep regret at the level of fame "Catcher" brought him, and, as was revealed after his death in 2010, the novelist avoided publication for more than half a century after. He left behind a selection of works never intended for public consumption, but which may soon see the light of day.

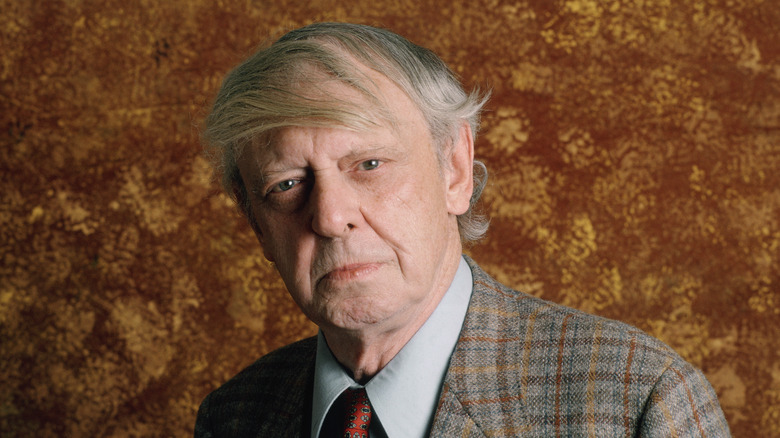

A Clockwork Orange

A classic book that inspired an even-better-celebrated film, British novelist Anthony Burgess' "A Clockwork Orange" is still as shocking a read today as it must have been back when it was first published in 1962. Centered around a gang obsessed with sex and ultraviolence, the strange atmosphere of the novel is heightened by the use of "nadsat," a hybrid patois of Burgess' own invention made up of corrupted words taken from Russian and Malay.

A stylistic tour-de-force, there is little wonder why it proved to be a great inspiration to the legendary director Stanley Kubrick, who used the novel as the source material of an even more controversial film released in 1971. Burgess found himself having to repeatedly defend Kubrick's work, and he eventually became resentful that "A Clockwork Orange" remained the most famous of his more than 50 books.

In his book, "Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D.H. Lawrence," Burgess decisively disowns "A Clockwork Orange," admitting that he wrote it simply for money in the space of three weeks. The problem, he believes, is that it was written in such a way that it was liable to be misinterpreted by readers, who might see it as celebrating violence, especially in light of Kubrick's famous film.

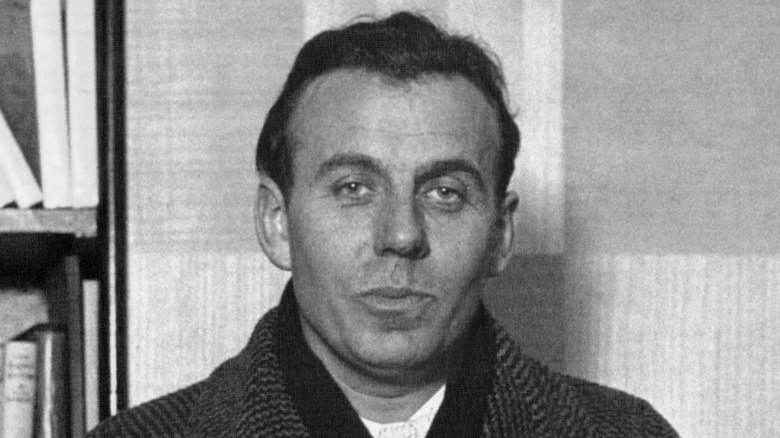

Journey to the End of the Night

An even-more-major stylist of the 20th century was the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose novel "Journey to the End of the Night" cast a long shadow on the form of the novel on both sides of the Atlantic in the decades after its publication in France in 1932. A pessimistic panorama of the age through the eyes of a physician likely modeled on Céline himself, "Journey to the End of the Night" is notable for its impassioned and at times amusing misanthropy, as well as its world-weariness and protagonist's anti-hero persona.

But Céline is also one of the century's most problematic writers, who, despite his influence, went on to become a Nazi sympathizer. The novelist made his support for the German forces public upon their occupation of Paris and made steps to support their propaganda campaign with the publication of overtly anti-Semitic works. When the Nazis were defeated in 1945, he was forced to exile himself to Denmark to avoid facing justice for being a collaborator.

Nevertheless, Céline's most famous work continued to be reprinted after his wartime disgrace. But the writer made clear in a preface to the 1952 edition how little he cared for continuing to give "Journey" to the reading public. "If I weren't under so much pressure, forced to earn my living, I can tell you right now, I'd suppress the whole thing, I wouldn't let a single line through."

The Anarchist Cookbook

There are few books more controversial in the history of publishing than Andrew Powell's "The Anarchist Cookbook," a guide to subversive and violent criminal activism that includes instructions on how to grow and synthesize your own drugs, handle weapons, and build deadly bombs and mantraps. Written in 1969 at a time of great social upheaval and division, "The Anarchist's Cookbook" became a cult hit among the disenfranchised and politically radical youth of the day.

It goes without saying that many were appalled at the existence of such a work, though it did have its admirers among those who weren't exactly the extremist social destructors that the "Cookbook" theoretically catered for. In an introduction to a later printing, P.M. Bergman described the book as "brutal," but noted that it wasn't exactly anarchists who were reading it — rather, it was a work of titillation to those who were disturbed by the supposed extremism of the movement's activism.

Powell himself, however, grew to regret the book and eventually disowned it for its apparent willingness to promote violence. As he wrote in an article in The Guardian in 2013, his book may be considered a savage cry against U.S. brutality in the Vietnam War and the horror Powell felt at potentially being drafted. "The continued publication of the Cookbook serves no purpose other than a commercial one for the publisher[,]" Powell wrote, ending his article with a call from its publishers to cease printing it.

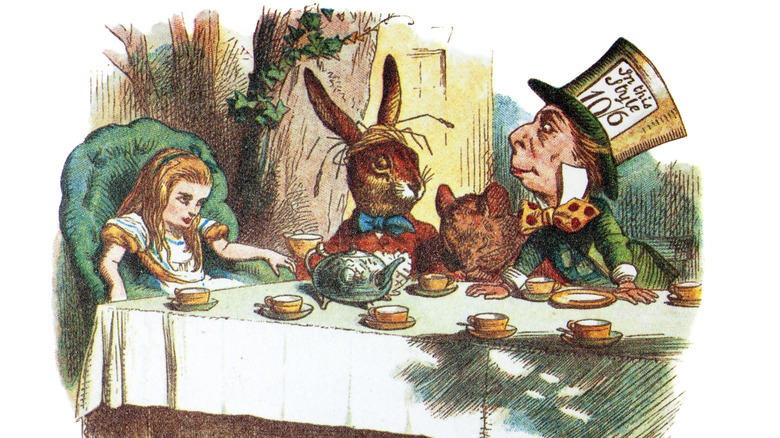

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

To write an all-time classic that stirs the imaginations of readers long after you're gone is surely the dream of any writer. But for Charles Dodgson — aka Lewis Carroll — the British author responsible for the deathless "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" and its sequel, "Through the Looking Glass: And What Alice Found There," published in 1865 and 1871, respectively, literary fame was a poor prize for his artistic brilliance.

Based on and originally written for the daughter of his friend, Henry Liddell, the novels became inescapable in the Victorian era and beyond, exhibiting an imaginativeness lacking from much of the children's literature of the day and chiming perfectly with the era's love of literary nonsense.

But in his own lifetime, Carroll found the level of fame that the Alice adventures brought him was too much to bear. In 2014, an 1891 letter written by Carroll to a friend named Mrs. Symonds was put up for auction, which revealed that Carroll deplored the lionization he experienced as a famous writer to such an extent that he wished that he had never written them.

My Struggle

Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard's "My Struggle" is a six-part work that delves into the author's recollections of his own life in staggering, mesmerizing detail. What's more, Knaussgaard has proven to be a confessional writer to the extreme degree, sharing with his readers his innermost thoughts — however distasteful — and the intimacies of his real-life relationships. With the publication of part one in 2009, Knausgaard became a literary sensation in his native country, and as the books began to be translated into other languages, he became one of the most celebrated literary authors of the century so far.

But while Knausgaard may be pleased to have received such widespread critical acclaim, he has turned away from stardom, ceasing to make public appearances and moving with his family to a remote home in rural southern Sweden. Knausgaard has revealed his immense feelings of guilt around how he put his closest relationships in the public eye, without the consent of those involved, which caused many rifts in his social circle. According to The Guardian, he has likened the feeling to apologizing after committing murder.

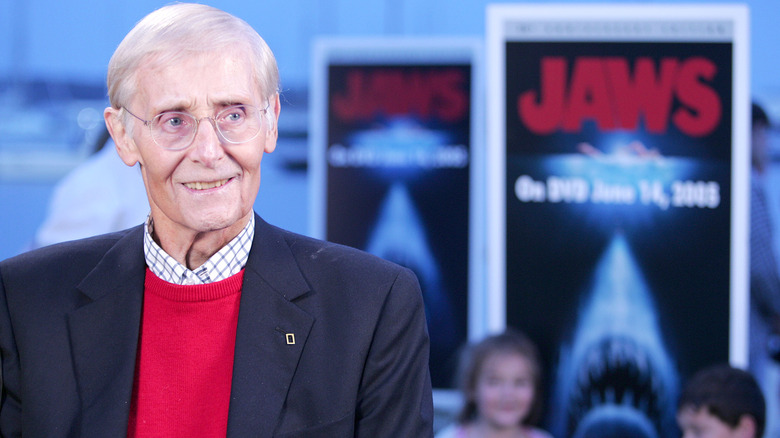

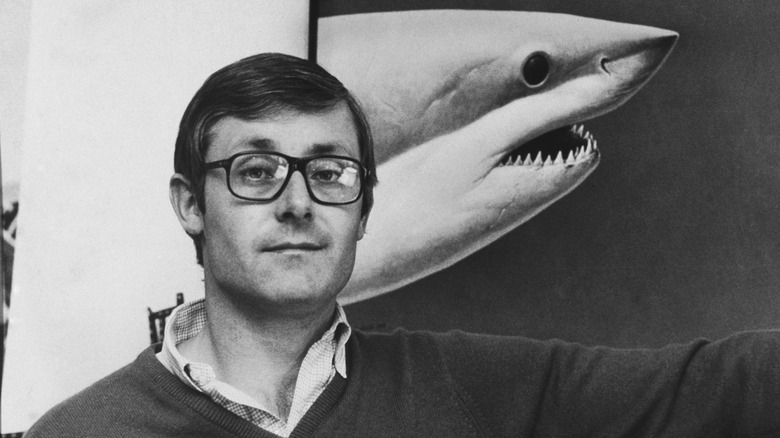

Jaws

Steven Spielberg's classic film "Jaws" — with its taut, adrenaline-inducing theme music — has one of the most famous blockbusters ever released. So much so, in fact, that it is reasonable to forget that the movie was based on a novel of the same name by the author Peter Benchley, published just a year before the movie's 1975 release. The novel sold 20 million copies, while Benchley also co-wrote the screenplay for Spielberg's adaptation.

Benchley, however, was filled with such deep regret with regard to how the hit movie instilled in the public a fear of sharks, recognizing that its portrayal of the sea creatures as unfailingly dangerous predators was utterly false. Benchley later became a noted campaigner for shark preservation, which he promoted throughout his life.

Even in his final days, Benchley was so vocal in his campaign to tell the world about the inaccuracies in his famous film-inspiring novel that he effectively disowned it entirely, telling the London Daily Express (via The New York Times): "'Jaws' was entirely a fiction. Knowing what I know now, I could never write that book today. Sharks don't target human beings, and they certainly don't hold grudges. There's no such thing as a rogue man-eater shark with a taste for human flesh."

Little Women

Louisa May Alcott's "Little Women" has gone down as an undeniable classic, with its enduring appeal recently confirmed by the 2019 movie directed by Greta Gerwig and starring Emma Watson, as well as a miniseries by BBC/PBS. A captivating coming-of-age tale centering around four unforgettable characters, it is just as popular today as it was at the time of its publication a century and a half ago.

Popular with readers, that is — but not so popular with Alcott herself, who reportedly hated the novel that made her famous. Alcott much preferred writing suspense-driven potboilers, and reportedly had little interest in marriage or courtship — major themes in "Little Women." In fact, it wasn't even Alcott's idea to write a novel focussing on growing up and marrying. She wrote it at the behest of a friend who worked for her publisher as a way of breaking into the growing market for literature aimed at children. It has been reported that Alcott grew to despise the work, even after its initial success, and in the writing of the sequels, contemplated killing the cast of characters in an earthquake.

Winnie-the-Pooh

This one might be a heartbreaker, but the fact is that the creator of some of the world's most beloved children's characters — Winnie-the-Pooh, Piglet, Tigger, Eeyore, and Christopher Robin, modeled on the author's own son — came to regret that he ever created them.

A.A. Milne had a long and varied writing career but hit the big time with his first children's book featuring Pooh, "The Hundred Acre Wood," the principal characters for which he based on toys in his young son's nursery room. Published in 1926, the book outsold his previous work for children by a 3:1 ratio, and led to his writing several more works set in the same world. The tales of Pooh and his friends are today considered children's classics.

But in Milne's autobiography, "It's Too Late Now," originally published in 1939, he admitted that he soon grew tired of writing for child readers and shared his frustration at how Pooh had come to overshadow his writing for adults in the form of novels, plays, and screenplays. He was equally frustrated at how critics tended to interpret his other work through the lens of Pooh, even going so far as to suggest that one of the characters in a play he had written was intended to be an adult version of Christopher Robin. Milne later became estranged from his son, who resented his father using his name and the characters of his childhood for fame and fortune.

The Spy Who Loved Me

"The Spy Who Loved Me" is one of the most recognizable titles in the James Bond cinematic universe, thanks to the massive commercial success of the big-budget movie following its release back in 1977. But the story of the novel by Bond creator Ian Fleming is far more checkered than that of the Roger Moore blockbuster.

"The Spy Who Loved Me" was the tenth James Bond book, published in 1962. By this time, Fleming was reportedly growing concerned that he was losing control of his creation; instead of catering to a sophisticated adult market, his books were becoming the reading material of schoolchildren, who failed to see the incongruities in the title character and instead venerated the spy as an all-out hero. With "The Spy Who Loved Me," Fleming decided to write an overtly moralistic novel with a female protagonist, who tells a gritty backstory and who observes Bond from a distance.

Unfortunately, both critics and readers hated it, not least because Bond only appears in the final pages of the book. Fleming later wrote to his editor apologizing for his experiment, instructed them to forego reprinting the work, and also, when it came to selling the movie rights, sold the title only, insisting that no plot elements could be used.

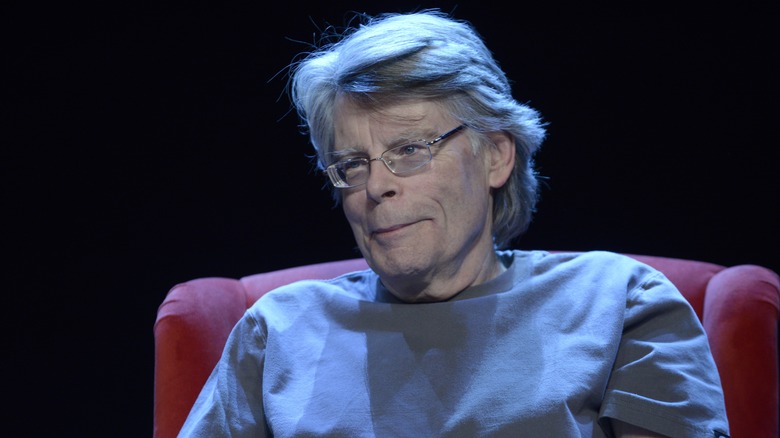

Rage

The "King of Horror" Stephen King hasn't exactly shown himself to be overly concerned with how his novels might affect the minds of his millions of readers. From "The Shining" to "Carrie," from "Misery" to "Pet Sematary," time and again King has produced work that continues to haunt the American psyche.

But while most of the novels published over the course of King's long career continue to find new readers, there is one that the author himself decided to suppress: the 1977 novel "Rage," published under King's alias Richard Bachman. The novel tells the story of Charlie Decker, a teenage school student who murders his teachers and holds classmates hostage in his school, prompting a stand-off with the police. King notes in his introduction to the 1985 anthology, "The Bachman Books," that shortly after its publication, "Rage" was linked to a number of potential crimes that the FBI — who interviewed King — suspected were inspired by the book. Though King admitted to "sleepless nights" as he ruminated on the responsibility an author has over the influence their work on real-world events, he ultimately put the responsibility on the reader, with an appeal to those who might emulate Decker to "pick up a pen instead."

However, in a lecture on gun violence delivered in 1999, King recalled that the perpetrator of a school shooting had kept a copy of "Rage" in his locker. King withdrew the book from publication, saying he did so with a sense of "relief."

If you have been impacted by incidents of mass violence, or are experiencing emotional distress related to incidents of mass violence, you can call or text Disaster Distress Helpline at 1-800-985-5990 for support.