The Untold Truth Of 1964's Freedom Summer

Also known as the Mississippi Summer Project, Freedom Summer was a multi-faceted volunteer campaign that sought to increase voter registration among Black residents in Mississippi. But the campaign did more than just help Black people register to vote. It also provided a variety of services to Black people, including education, legal counsel, and medical aid.

The volunteers who worked with Freedom Summer accomplished all of this in a hostile and violent environment, as white supremacists ranging from residents to police officers tried to intimidate them into giving up their work. Over the course of three months, blood was spilled on numerous occasions as Freedom Summer tried to provide Black people in Mississippi with services they had a right to receive. Ultimately, this level of violence was nothing new for Black Americans, but some of the white volunteers who worked with Freedom Summer saw for the very first time the levels of brutality that Black people in America faced every day.

But amid all the violence, thousands of Freedom Summer volunteers persevered. And the legacy of Freedom Summer was not soon forgotten.

Voter registration in Mississippi

In the early 1960s, voter registration among Black people in Mississippi was between 5 and 7%, due in large part to the state's racist Jim Crow laws. Despite making up roughly 40% of the population, many Black people would face harassment or violence and suffer financially if they tried to register to vote. Additionally, the state constitution required voters to interpret the constitution and be "of good moral character," and left it up to the white local registrars to determine who qualified. The situation was similar in other Southern states such as Alabama, where only 10.3% of Black residents were registered to vote.

In some cities like McComb, Mississippi, only around 2% of Black residents were registered to vote. And when activist and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader Bob Moses set up a voting rights project in McComb in 1961 in order to register more Black residents to vote, the white residents of McComb responded promptly with violence and intimidation. According to the Civil Rights Movement Archive, white residents harassed Black communities every night as they drove around the streets firing their weapons, led by both the Citizens' Councils of Mississippi and the Ku Klux Klan. And after staging a sit-in by ordering a hamburger at a lunch counter in McComb in order to bring awareness to Black voter registration, 15-year-old Brenda Travis was sentenced to one year imprisonment in a state juvenile prison.

1963 Freedom Vote

Against the efforts of Black voter registration, people like Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland claimed that "all who are qualified to vote, black or white, exercise the right of suffrage," per "Black, White, and Southern" by David Goldfield. Meanwhile, activist Fannie Lou Hamer didn't even realize Black people could register to vote until she was 45 years old. In order to show that Black people were in fact interested in exercising their right to vote, activist Bob Moses set up a mock election with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) in June 1963 for Black residents to participate in prior to the Democratic gubernatorial primary between Paul B. Johnson Jr. and James P. Coleman.

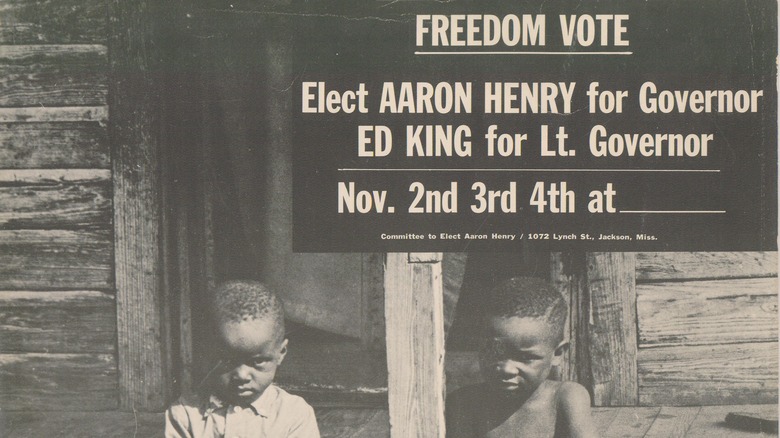

Known as the 1963 Freedom Vote or Freedom Election, over 27,000 Black residents of Mississippi participated. And when another mock election was held in November along with the statewide election, more than 80,000 ballots were cast. During this second election, in addition to the Democratic candidate Paul B. Johnson Jr. and the Republican candidate Rubel Phillips, the COFO included NAACP leader Aaron Henry on their ballot.

Even a mock election was seen as a threat by the white residents of Mississippi. As Henry traveled around Mississippi campaigning, firefighters drowned out his words with sirens during at least one rally, claiming there was a fire and that they were just doing their jobs. Undeterred, Henry shouted over the sirens that "the fire within us cannot be extinguished with water!" per SNCC Digital.

Finding volunteers

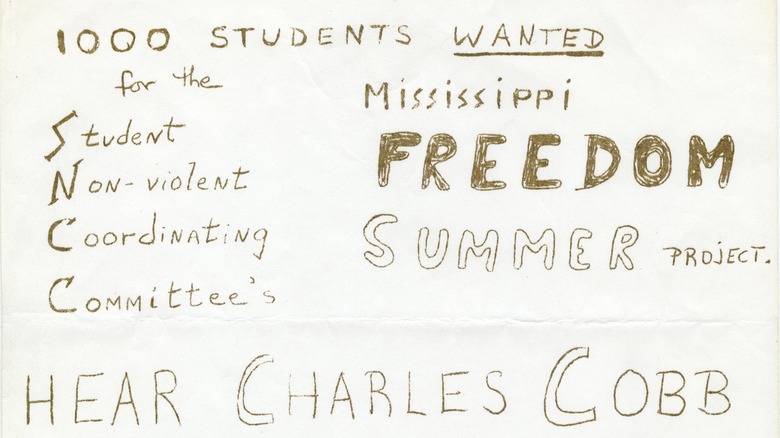

Inspired by the success of the Freedom Vote, Bob Moses continued to plan a mass Black voter registration drive in Mississippi until Freedom Summer was ready to begin in June 1964. However, a widespread voter registration effort required many volunteers.

Thousands of Black residents of Mississippi participated in Freedom Summer, but considering the ire that Black voter registration drew, the dangers involved with Black activists advocating registration in public was a very real consideration. White people regularly murdered Black activists in Mississippi with little to no response from the local police. But the SNCC realized that if violence was directed at white activists from Northern states, there would be more of a chance that the media both in the South and the North would report the story and force the federal government to step in.

As a result, organizers decided to recruit white volunteers from Northern states, although the idea drew criticism due to the fear that white activists would appropriate the movement or take on the role of a white crusader, a phenomenon attributed to "a John Brown complex," according to Mark Kurlansky's "Ready for a Brand New Beat." Many also worried that the white volunteers would draw attention from the KKK and the Citizens Council. It was decided to bring in 100 white college students for the 1964 campaign, but ultimately between 700 and 1,000 white volunteers from Northern states signed on to participate in Freedom Summer.

Freedom Summer voter registration

In mid-June, white volunteers gathered at the Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio, where they received training both in how to advocate for voter registration among Black people and how to deal with police brutality. After their training session, the volunteers started arriving in Mississippi by June 21, 1964. In "Freedom Summer," Bruce Watson writes that in May 1964, a one-year injunction was issued against the Mississippi requirement that voter registration involve an interpretation of the constitution and a prohibitively expensive poll tax. This meant that it would be a little easier for Black people to register to vote, and the SNCC promptly managed to get 47 people registered.

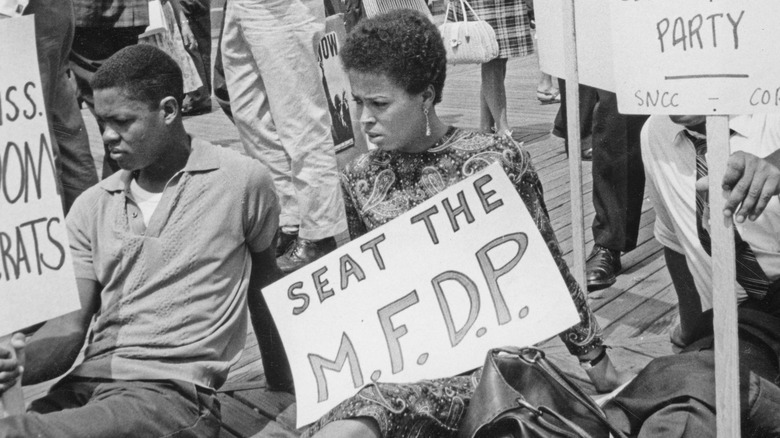

Freedom Summer volunteers went door-to-door throughout Black neighborhoods in Mississippi for two and a half months asking Black people to register to vote. But although roughly 17,000 Black people subsequently tried to register, only 1,600 were successful. In addition to registering people to vote in the state of Mississippi, volunteers also collected registration forms for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which didn't require any literacy or morality test.

The volunteers were known as Freedom Riders and typically went out in pairs. They were frequently harassed and arrested by the police for various invented crimes — even speed walking. According to "A New History of Mississippi" by Dennis J. Mitchell, police officers also seemed obsessed with the idea of interracial sex and often asked white volunteers weird and intrusive questions.

Offering health care

In addition to promoting voter registration to Black residents in Mississippi, Freedom Summer volunteers also worked to offer health care services to Black people. Known as the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR), around 100 medical volunteers offered their services to Black residents in Mississippi. By mid-July, the MCHR had established six health centers across the state. And despite the fact that the Mississippi Department of Health refused to provide medical licenses to the doctors or nurses working for MCHR, according to Harvard University, the fact that anyone is allowed to administer emergency first aid was used to justify any treatment offered to Black residents. The MCHR was so successful that by September 1964, it became a permanent and national organization that lasted until the 1980s.

The volunteer doctors who worked with Freedom Summer also came to provide services to Freedom Summer activists. Few Black doctors were willing to publicly support the Freedom Summer movement, and even fewer were willing to treat white Freedom Summer volunteers due to the strict lines of segregation.

Because of the lack of resources, the assistance provided by the MCHR was fairly rudimentary, but it addressed the basic medical needs of the Black community that were being ignored by the white medical community. Their work included dressing wounds, making meals, helping people access basic medical supplies, physical examinations, and other routine health care services.

Providing legal support

Because of all the police attention that the Freedom Summer volunteers attracted, volunteers from several legal organizations, including the NAACP, the National Lawyers Guild, and the ACLU, offered their services to the effort. The NAACP reportedly threatened to pull their support if Freedom Summer also accepted help from the National Lawyers Guild because of the latter group's defense of Communists, labor unions, and gay people, but ultimately both organizations ended up providing support to Freedom Summer. However, the NAACP only offered support at a local level, while NAACP chief Roy Wilkins told the media, "We're sitting this one out," per the Civil Rights Movement Archive.

Lawyers volunteering to help with Freedom Summer, including Marian Wright Edelman, also provided services to Black residents in Mississippi in cases ranging from welfare rights to desegregation in schools. After becoming the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, Edelman provided legal services to both Freedom Summer volunteers and Black residents of Mississippi. And doing so wasn't free of risk. There were over 50 bombings during Freedom Summer, and Edelman always started her car with the driver's door open in order to be thrown from the vehicle in the event of a bomb, Harry G. Lefever writes in "Undaunted by the Fight."

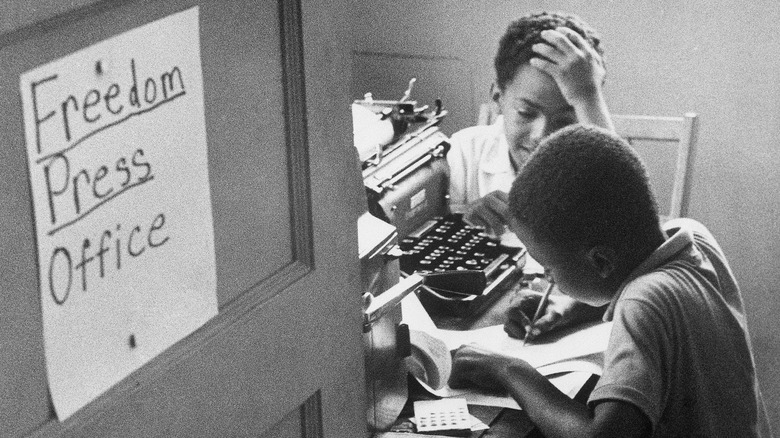

Freedom Schools

Another accomplishment of Freedom Summer was the establishment of Freedom Schools. The education that was offered to Black people in Mississippi in the 1960s was abysmal. Not only were schools for Black children typically closed during the spring and fall sharecropping seasons, but schools actively engaged in historical revisionism. The Civil Rights Movement Archive reports that schools in one district were told that "neither foreign languages nor civics shall be taught in Negro schools. Nor shall American history from 1860 to 1875 be taught," in order to deprive both Black and white students of the fact that during Reconstruction, Black people had numerous civil rights, including the right to vote.

Over the course of six weeks, Freedom Schools provided an education to Black residents of Mississippi ranging from young children to elderly grandparents. The schools operated out of church basements, stores, and community homes and offered lessons ranging from humanities and history to math and reading.

Over 40 Freedom Schools were created across Mississippi, providing educational services to roughly 3,500 Black people. But unfortunately, even the Freedom Schools were plagued by harassment and attacks. On September 20, 1964, the Society Hill Baptist Church was bombed for housing a Freedom School. A Freedom School in Gluckstadt was also the victim of an arson attack. But despite these attacks, students continued to show up for classes.

Freedom Libraries

Another educational component of Freedom Summer was the establishment of Freedom Libraries. Across the state of Mississippi, at least 25 Freedom Libraries were established using books that were donated to the campaign.

Because of racist and segregationist laws, Black people in Mississippi weren't able to use public libraries. And even when they could get books from the school system, the books they received were either censored, in poor condition, or both. According to "To Write in the Light of Freedom," edited by William Sturkey and Jon N. Hale, it was through the Freedom Libraries that some Black people were able to access books by Black authors like James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and Zora Neale Hurston for the first time.

Freedom Libraries were also targeted and bombed. In Greenville, Mississippi, the delivery truck for the library had its tires slashed numerous times. And according to The Washington Post, at least one library experienced repeated telephone calls where the person on the other end of the line would either threaten violence or ask intrusive, offensive questions.

Violence against Freedom Summer

During the three months of Freedom Summer, every single project that was organized experienced harassment and violent attacks by police, the KKK, and white residents. Over 60 buildings were bombed and 80 people were assaulted. Meanwhile, police arrested up to 1,000 Freedom Summer volunteers for invented infractions. And up to 15 people working with Freedom Summer were murdered. McComb, Mississippi, experienced so many bombings that it was referred to as "the bombing capital of the world."

There were so many attacks that some of the Freedom Summer volunteers ended up surviving multiple bombings just over the course of a single summer. According to The New York Times, even the home of John Nosser, mayor of Natchez, was bombed because he was trying to walk a middle ground.

The KKK bombed, harassed, kidnapped, assaulted, and murdered those who were associated with Freedom Summer in any way. And the local police never made a single arrest in relation to any of the attacks. In a letter home about the violence, volunteer Thomas Foner wrote, "As I write this letter, a Negro church is burning down the street; the fire department is nowhere to be found. Two other volunteers have just been arrested. Last night a Negro freedom worker was shot by white hoodlums," per Timeline.

The Freedom Summer murders

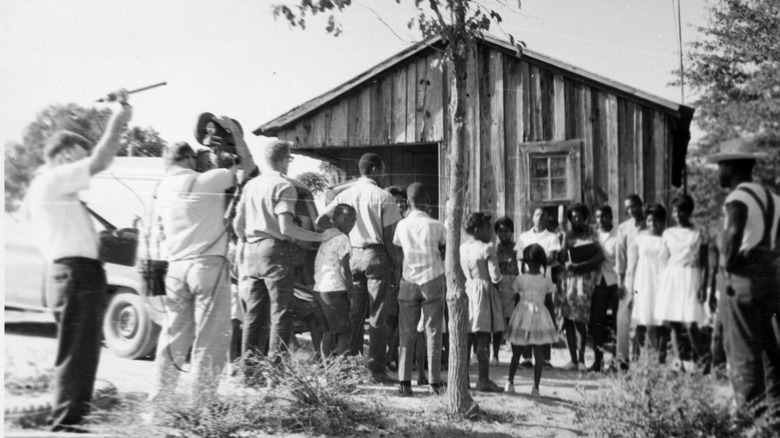

The violence against Freedom Summer started immediately, and during the first weeks, three Freedom Summer volunteers were murdered by the KKK. On June 21, 1964, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner disappeared after being stopped by the Neshoba County police. After being taken to the Philadelphia jail around 4 in the afternoon, the three men, all in their early 20s, were reportedly released around 10 at night after paying a speeding fine. Tragically, they were never seen alive again.

In response to the kidnapping and disappearance of one Black man and two white Jewish men, the FBI sent more than 200 federal agents into Mississippi. Their car (pictured) was found two days after their disappearance, almost burned beyond recognition. Their bodies were found on August 4, 1964, and revealed horrific levels of violence. According to "Race And Ethnic Conflict" by Fred L. Pincus, Chaney was beaten so badly that a pathologist claimed that he'd "never witnessed bones so severely shattered, except in tremendously high speed accidents such as aeroplane crashes."

In October 1967, seven people involved in the murders were convicted, including Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price and KKK Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers. These were reportedly "the first ever convictions in Mississippi for the killing of a civil rights worker," per the University of Missouri's Douglas O. Linder. Edgar Ray Killen, whose 1967 trial ended in a hung jury, ended up being convicted over 40 years later for planning and directing the murders.

Finding other bodies

During the search for James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, federal investigators found the bodies of other Black people who'd been murdered in Mississippi. As investigators searched rivers for the bodies of the three murdered civil rights workers, they ended up finding the bodies of eight Black boys and men. Although five bodies were never identified, three were identified as 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby and 19-year-olds Henry Hezekiah Dee and Eddie Moore, according to the Zinn Education Project.

Until the bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were found, many people, including President Lyndon Johnson, called the kidnapping a hoax. But considering how many other bodies were found during the search, it was clear that local police had little interest in solving the murders of Black people. After their kidnapping made national headlines, even Schwerner's wife, Rita, addressed the racist discrepancy, saying that, "The slaying of a Negro in Mississippi is not news. It is only because my husband and Andrew Goodman were white that the national alarm has been sounded," per the Equal Justice Initiative.

Legacy of Freedom Summer

In the short term, the successes of Freedom Summer were a mixed bag. When it came to their original goal of Black voter registration, they fell short, only registering about 1,600 new voters. However, the long-term impact of Freedom Summer cannot be understated. According to "Faces of Freedom Summer" by Bobs M. Tusa and Herbert Randall, the efforts of Freedom Summer volunteers and the testimony of MDFP members such as Fannie Lou Hamer led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Although some of the projects, such as the health services and the Freedom Schools, weren't sustainable in the long term because many of the volunteers left after the summer, the Freedom Schools also led to the establishment of the Children's Defense Fund by Marian Wright Edelman in 1973, which continues to advocate for child welfare and public education as of 2023.

Freedom Summer also brought the racism and brutality that Black people in Mississippi dealt with onto a national stage, largely due to the widespread media attention the campaign attracted.