Things Found In Old Churches That Caused A Stir

An old church might seem to be downright boring at first. Sure, it can be a beloved house of worship and, if you're interested in talking about the key differences between Romanesque and Gothic architecture, a sufficiently old church is just the place to get the conversation going. Beyond big-name cathedrals, however, it can be hard to get everyone interested. Perhaps, at some point in the past, these churches were witness to dramatic history, but today they're just for parishioners and tourists, right?

History has a way of surprising you, though. When it comes to old churches, sometimes a good rummage in the basement — or just behind the altar — is enough to get eyebrows raising and tempers flaring. Even something as classic and pretty as a stained glass window could get a serious argument going once you take note of some key details. And if you ask a church official or caretaker about that shocking relic on display, you may be in for either a rollicking story or a good talking-to.

St. Catherine of Siena left behind an especially dramatic relic

Enter the Basilica of San Domenico in Siena, Italy, and you will see that the outwardly simple if monumental church contains complex carvings, intricate paintings, and likely more gold leaf than you have decorating the interior of your home. But the most eye-catching thing of all is the mummified head believed to be of St. Catherine of Siena.

Catherine also generated upset during her short lifetime. Born in 1347, she was subject to intense, mystical visions from a young age. She eventually became an influential writer, persuading Pope Gregory XI to center the Catholic church in Rome again after many years in Avignon, France. Today, she remains famous for her stigmata and dramatic visions, which included a heavenly ceremony in which she married Jesus. The wedding ring, she claimed, was the savior's circumcised foreskin, though only Catherine could see it sitting on her finger.

Things kept on being weird after she died in Rome at just 33. When representatives from Siena wanted to repatriate her body after her canonization a century later, they found that the Romans were reluctant to give her up. So, they did the next best thing: stole her mummified head from the basilica where she had been buried. As the story goes, the corpse smugglers were stopped by a guard who insisted on peeking into their bag but then saw only rose petals. When the group returned to Siena, the bag revealed Catherine's head again.

Bones found in a British church might belong to an Anglo-Saxon saint

Bones are seemingly everywhere in old churches, but one set generated a lot of interest in 2020. The bones in question were actually uncovered in 1885 in the church of St. Mary and St. Eanswythe in Folkestone, Kent. Speculation immediately turned to one of the church's namesake saints, Eanswythe, a young woman believed to have been an early nun and founder of one of the first monasteries in Britain around A.D. 660. But little could be done to prove the bones belonged to the saint.

In 2020, researchers were able to study the remains with modern equipment. They found that the individual was female, died in her late teens or early 20s, and lived a relatively leisurely life. Eanswythe, who died young and was the granddaughter of a king, certainly fit the bill. Radiocarbon dating of the bones indicated the person lived in the middle of the seventh century. Andrew Richardson, with the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, told The Guardian that this was probably Eanswythe herself. Given her link to the early history of Christianity in Britain, this constituted a major find.

But, if the identification is as close to certain as we're ever going to get, why were these bones tucked away in a wall and not put on display? Excavators speculate that someone hid the casket as representatives of the anti-Catholic Reformation moved through the country's churches, destroying relics they deemed to be idolatrous.

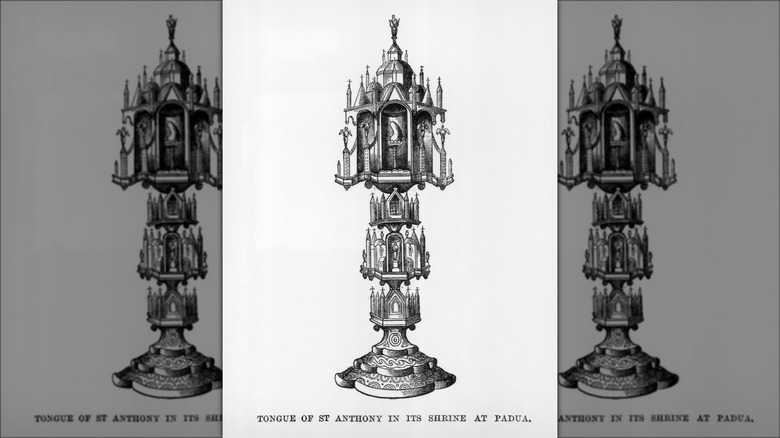

St. Anthony's tongue and jaw are kind of a big deal

People who go mucking around in church crypts must be looking to cause a ruckus. Sure, some might be satisfied if they only see old graves and perhaps a nice carving, but everyone must hold out at least the secret hope that they will find something truly shocking down there. For the people who exhumed St. Anthony of Padua from his initial resting place, they were in for something truly strange. They knew that Anthony, a Franciscan monk who had died three decades earlier in 1231, was a holy man who was renowned for his preaching. They intended to rebury the deceased saint in a nice, new basilica, so at least they had a good excuse. And perhaps, like it was rumored to be for other holy men, his body would be free from rot and so deemed incorrupt.

It was — kind of. As the story goes, by the time of his exhumation in 1263, most of Anthony's body had decomposed, leaving behind only scattered bits of bone. Yet his tongue looked just like new, to the point that some claimed it was still wet with spittle. Suitably impressed, someone built an ornate reliquary that still houses the tongue hundreds of years after it was plucked out of the grave. In 2013, it even went on an international tour alongside what's believed to be the saint's jawbone and a bit of his left arm, also displayed in richly-decorated reliquaries.

One stained glass window provoked questions about race

Stained glass windows are a common feature of Christian churches that can range from simple to ornate. Yet, rarely are they really all that shocking, especially for churchgoers who are already familiar with the Bible. That is, except for one window found in a small, long-unused church in Warren, Rhode Island. The church in question, St. Mark's Episcopal Church, first opened its doors in 1830, closed in 2010, and then was purchased years later by Hadley Arnold and her family. In 2020, four large stained glass panels dating to the 1870s were removed from the old building.

Seen in the light of day after many years in obscurity, one window caught Arnold's attention. It showed Jesus in two Biblical scenes, a pretty common subject, but everyone depicted in those scenes had brown skin. This was no byproduct of aging materials, either. Professor Virginia Raguin of the College of the Holy Cross told the Associated Press that the panels were in good condition, and the figures were intentionally given darker skin.

It was especially striking to see a Jesus of color here, given that 19th-century Rhode Island was not necessarily the most diverse place in the nation. Arnold speculates that it may have been commissioned in honor of two women who had links both to slavery-supported businesses and more abolition-adjacent causes. Raguin also noted the significance of the scenes, which show Jesus interacting with women as equals, perhaps pointing to an overarching theme of egalitarianism.

Some very direct stone carvings make churchgoers blush

The next time you're in an old church, you might discover some rather naughty carvings in Ireland, Britain, Spain, and France. Popularly known as sheela-na-gigs, these female figures are all nude and very directly exposing their privates to the viewer. It's certainly a shocking sight for modern visitors, who hardly expect to stumble across sheela-na-gigs in medieval churches — not exactly places known for free-wheeling sexuality then or now.

Even in the past, this may have been a bit much. Some figures appear to have been discarded and even burned in an attempt to do away with them. Others were left in place but defaced by shocked Victorians and even modern folks with a serious puritanical streak. Sheela-na-gigs are sometimes joined by other more-than-suggestive figures, including those who are very proud of their male anatomy and some who are going to the bathroom in the open.

So, why did carvers make and place these figures in the very same churches where priests might thunder against the sin of lust? Some people argue that this was exactly the point. It could be that sheela-na-gigs represent monstrous sexuality and would have acted as warnings against enjoying one's self too much (though quite a few appear to be smiling in defiance of such a notion). Others say they represent survivals of pagan goddess worship, acted as fertility boosters for newly married women, or lent some protection to anyone facing the dangerous ordeal of childbirth.

[Featured image by Sarah Smith via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Jesus' home might just be beneath one old church

Pinning down evidence of a historical Jesus is pretty difficult. Sure, there are the biblical accounts of his life, as well as a spare couple of mentions by historians like the first-century Flavius Josephus, but physical evidence is lacking. And, no, so-called relics like the Shroud of Turin or pieces of the True Cross are all but impossible to substantiate.

That may be why one archaeological excavation stirred up interest in 2020. University of Reading Professor Ken Dark's work at a convent in Nazareth uncovered the remains of an ancient house dating back to the first century AD. Actually, the home was described back in the 19th century, when it was found beneath the more recent remains of a Byzantine church. Archaeologists back then got fairly excited by suggesting that this home, skillfully carved into a hill, might just have been constructed by a tekton (a Greek term for what was essentially a general contractor, which is often mistranslated as a carpenter).

Well, many of us know about one first-century carpenter from Nazareth who made a real name for himself. Could this be the home of a young Jesus? Though the idea fell out of favor in the 20th century, Dark brought it back to the fore in the 21st century. However, while academics and laypeople may both enjoy the speculation, it's not as if anyone's found ancient graffiti signed by Jesus inside, so this particular church find is still up for much debate.

Rumors of flayed Vikings caught attention for centuries

The Vikings have a pretty fearsome reputation overall, but they occupy an especially contentious place in British history. The first recorded Viking attack in the islands came in A.D. 793, when these Norse raiders descended upon the English monastery of Lindisfarne. They continued hitting English settlements for many years afterward, though both textual evidence and genetic analysis make it clear that some Vikings left their raiding ways and settled down in England.

However, perhaps not all Vikings were allowed the chance to settle down. Legend has it that British people were ready to strike back in revenge, and in gruesome fashion. Captured Vikings were supposedly skinned, and their preserved hides were put to use covering church doors. Often referred to as "Daneskins," these stomach-turning relics were reported to lie in churches throughout Britain, even supposedly showing up in national landmarks like Westminster Abbey.

Before you get too excited about that suspicious piece of leather nailed to a church door, though, you'd better call a scientist. After all, it was common for medieval doors to be lined with animal leather. Scientists presenting at the U.K. Archaeological Sciences Conference 2022 reported that they had tested skin fragments found on three church doors in England (via IFLScience). They discovered that the supposedly human-derived coverings all came from regular farm animals. Maybe some of the other breathless accounts were written by people who actually got all worked up over a cowhide.

[Featured image by Acabashi via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

One church contains alleged dragon bones

If you make a trip to Venice, there are plenty of things to see in this historic Italian city. There are the gondoliers making their way through the city's famous canals, for instance, as well as the grand architectural spectacles of Saint Mark's Basilica and the Doge's Palace. But, while these tourist-heavy sights are all well and good, you'll need to make your way to another heavily decorated church for a sight of something kind of strange.

It will take some looking, however. First, find the Basilica of Santa Maria e San Donato, a seventh-century church. Though it was originally meant only for one saint, San Donato (St. Donatus) was incorporated into the name in the 12th century. Like many other saints and their namesake churches, Saint Donatus' bones are said to be buried on site. What's weird, however, are the larger-than-human bones hanging behind the altar. They're said to be the bones of a dragon killed by Donatus. However excited people may have gotten over the supposed physical evidence of a fire-breathing monster, these probably come from a more mundane large mammal.

How Donatus killed the dragon is maybe even odder than the large animal bones hanging up in the basilica. Most accounts say that Donatus became aware of the dragon after it began poisoning a well. He first goes to simply pray the poison away but, when confronted by the creature, kills it by spitting on the beast.

[Featured image by Dimitris Kamaras via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.0]

19th-century workers found a grisly relic in one English church

While doing some repair work in Northamptonshire's St. Mary the Virgin church in 1866, workmen found a void inside a pillar. One reached in and found a crumbling wicket basket that contained a mummified human heart.

News of the shocking discovery soon spread through the surrounding village of Woodford. Some of the townsfolk claimed that they had encountered the ghost of a monk in the medieval church. Perhaps it was his heart, they speculated, though no one seemed able to come up with a good story as to why a holy man's heart would be pulled from his chest and entombed in the church.

Other people claimed that this is the organ of a Crusader who died far from home, but whose friends managed to transport his heart all the way from the middle east back to England. Somewhat more substantial evidence in a 1280 document indicates that the heart might have belonged to local noble Roger de Kirketon (or Kirkton), who died in Norfolk but whose heart was reportedly entombed in his home church at Woodford. Even today, despite all that back and forth, no one's still really sure who was the original owner of the heart. For the curious and skeptical alike, the delicate, mummified body part is still on view, placed behind glass after it was returned to its niche in the pillar.

[Featured image by Dave Kelly via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Multiple heads of St. John the Baptist make things confusing

The head of St. John the Baptist has generated plenty of controversy, given that there are four churches claiming to house the man's severed noggin. According to the biblical account of his death and basic human anatomy, however, we can reasonably conclude that John had just the one head. So, what's going on here?

John is a major figure in the New Testament, anticipating the arrival of Jesus as the Messiah and baptizing him in the River Jordan. He is later imprisoned by King Herod Antipas, who orders his execution by beheading. The fate of John the Baptist's head gets hard to follow after that. There are certainly plenty of different paths identified in folklore and uncertain records, though the Bible remains mum. One tradition holds that the head was buried at a church in Damascus, now the site of the Umayyad Mosque. Or did it get snagged by a crusader, who couriered the relic from Jerusalem to the cathedral in Amiens, France? Or, wait, perhaps someone took it to Rome and installed the head at the Church of San Silvestro in Capite.

As if that weren't enough, the Residenz Museum in Munich claims that a Bavarian duke claimed the grisly prize and installed it in his collection in the 16th century. Of course, all four spots display a skull that they say is the real deal, meaning that any awkward questions stand to cause at least a minor stir.

Some incorrupt saints make churchgoers confused or uncomfortable

Make a journey to a church to see an incorrupt saint's body, and you may be shocked to see that they're in pretty good condition. St. Bernadette, for instance, appears to be sleeping peacefully (even if she is encased in crystal). Not too bad for someone who died over a century ago. Only, if you were allowed a closer look, you would discover that Bernadette isn't in that great a condition. That lovely face is actually a skillfully crafted wax mask. Her hands are wax, too.

That's because officials who got a good look at her naturally mummified remains decided that the body was a bit too gross for public viewing. Upon the saint's second exhumation in 1919, it was covered in salts and mildew and had taken on an unnerving black tone. When it was first exhumed in 1909, Bernadette's body was in better shape, but mishandling left her remains the worse for wear. Still, the lack of decomposition was enough for some to decide that the holy woman had won God's favor. In 1925, her remains were transferred to their present spot.

Other incorrupt saints' bodies have less set dressing and so can seriously shock unprepared onlookers. St. Zita, who died in Lucca, Italy, in 1272, lies in the Basilica di San Frediano. There is no wax artistry between the viewer and this saint, however. Though her remains are lovingly cared for, Zita's skin has seriously dried out, presenting a starker interpretation of incorruptibility.

[Featured image by Jabonsbachek via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]