Things That Came Out About Frank Zappa After He Died

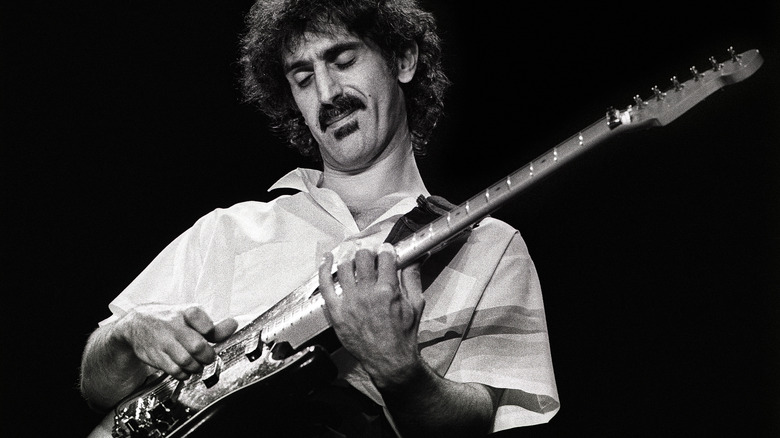

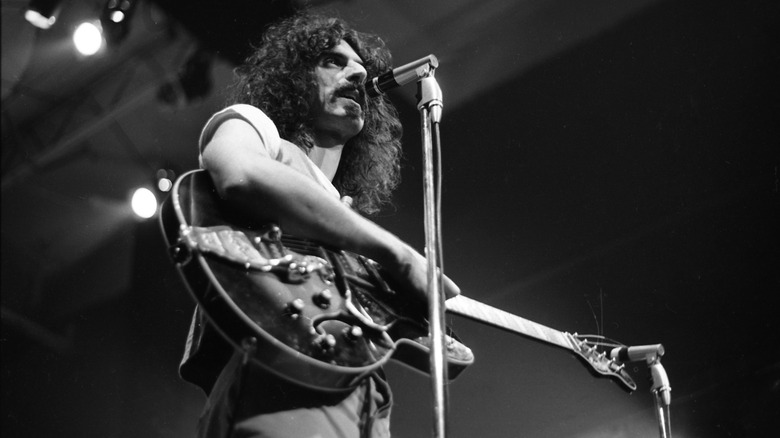

Never, ever in the history of music (probably) has anyone ever put on Frank Zappa and gotten a reaction of, "Sure, that's fine." While music is, by nature, something that falls into a few subjective categories — including "favorite songs," "background music," and "for the love of all that's good in the world, turn it off" — there are few artists that are as completely and totally polarizing as Zappa. Where one person might hear genius, another might hear a big ol' pile of trying-too-hard nonsense.

Zappa died in 1993, several years after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. His obituary was just as eclectic as his music, noting things like how big a fan of the president of Czechoslovakia he was; how he spread the trend of Valley-Girl-speak while trying to ridicule that very thing; and how he hated love songs but became a tireless champion for artists' rights. Appearing on television as a financial consultant? Going into business with the Soviet Union? He did that, too.

Even the biggest Zappa fans have to admit that he's more than a little unconventional, and in the years since his death, there have been some surprising things that have come out about the artist who once said (via the Los Angeles Times), "I write because I am personally amused by what I do, and if other people are amused by it, then it's fine. If they're not, then that's also fine."

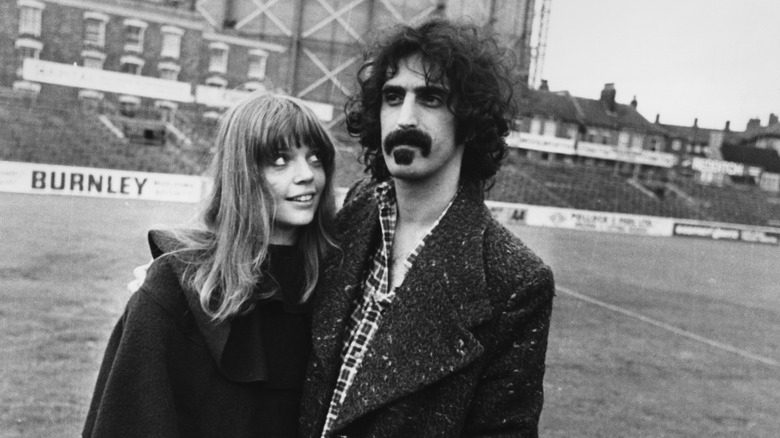

He wanted his wife to get out of the business completely

There are two different points of view when it comes to Gail Zappa: Critics say she made it all but impossible to share Frank Zappa's music with anyone, while supporters say she's just looking out for his memory and his legacy as an artist. She spoke with the Los Angeles Times and explained how she saw things: "My job is to make sure that Frank Zappa has the last word in terms of anybody's idea of who he is. And his actual last word is his music."

Between Frank's 1993 death and Gail's passing in 2015, she was nothing short of fanatical when it came to issuing lawsuits to everyone from cover bands to festivals, all the way up to suing record labels to get complete control over his work. Was that what he wanted? It turns out that it wasn't.

After his death, she said he'd made a final request of her: Sell all the masters he still had and retire from the music business once and for all. She added, though, that there was a loophole: He hadn't said anything about the rights to everything, so she decided to go against his final wishes, establish the Zappa Family Trust, and make sure everyone was doing Zappa the way that she thought he'd want.

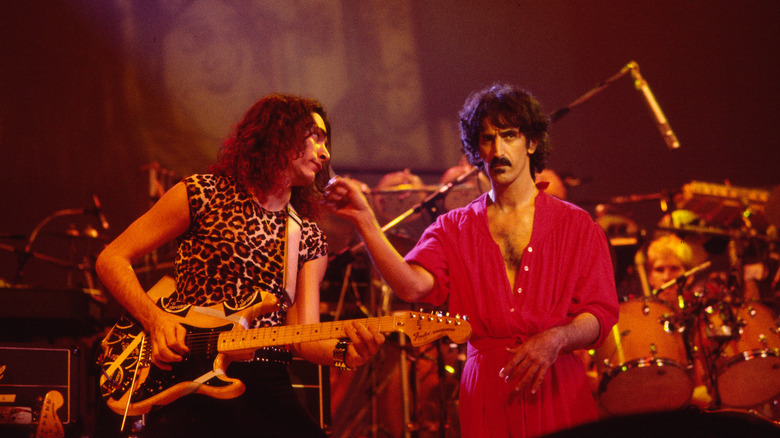

Zappa's friends say he wanted them to keep playing

It's no secret that Frank Zappa's legacy was made notoriously tricky by the ever-vigilant Gail Zappa, who would sue anyone and everyone who she thought was improperly using Zappa family property — including Zappanale, a German music festival that pre-dated Zappa's 1993 death. Gail Zappa explained to NPR that it's not about who's playing the music, it's about whether or not they go through her before doing it: "I don't really care who's doing it, as long as they get a license. The people I'm going after are not licensing the music."

At the top of the lawsuit hit list were cover bands, particularly those accused of not playing Zappa's music precisely the way he had written it. That, his widow argued, wasn't his music: "It's some wretched version of it."

But according to what cover band regular Ike Willis had to say, that's not the case at all. Willis — who regularly played with the cover band Project/Object — says that he spoke with Zappa just before his death, and he had something a little different to say when it came to his last wishes for his music. "He said, 'I would really like it if you could be one of the people that could actually keep my music played, in some way, shape or form.' Those were his words. He didn't want it to die." Just how that's going to happen, well, there were vastly different opinions on that.

He saved absolutely everything

Frank Zappa fans will be familiar with the idea that he saved a lot of stuff. But it was only after his death that archivists realized just how much stuff, going all the way back to home movies he shot as a kid.

In 2020, UDiscoverMusic spoke with the archivist in charge of cataloging and preserving what was there. It was a huge undertaking: "In the beginning days we didn't have the machines to play back the formats, so it was still a mystery as to what anything was because I couldn't play any of it," Joe Travers explained. "It took many years for Gail to refurbish the studio and get the machines needed for me to do my job." One of the most surprising things found in the vault? Recordings of a 20-piece and 10-piece electric orchestra that toured with Zappa only briefly before being disbanded. No one knew he'd kept recordings.

When Alex Winter waded into the vault to work on putting together his documentary "Zappa," he discovered something fascinating, too. He was working on the preservation of some of the materials when he came across what he thought were duplicates. They weren't. As he explained to AllMusic, "He'd take a piece of super-8 film, dupe it, and then he'd re-cut it and draw on it and put that to music and dump it on video. So, the vault was itself a giant artistic archival project of his that he never stopped tinkering with."

Zappa had a strict anti-drug stance

The wild creativity of Frank Zappa and the no-holds-barred attitude of the 1970s-era "Saturday Night Live" might seem like a match made in heaven, but his appearance was so bad that he was famously banned from the show. That said, one of the most memorable sketches was one in which Zappa groupies were amazed when he declined an offer of some illicit substances.

The whole thing is played as a joke, but as Alex Winter's 2021 documentary "Zappa" revealed, and also as Zappa's son, Ahmet, confirmed for ABC News, the unlikely-sounding story is absolutely true. Not only that, but Zappa didn't want those he worked with to do drugs, either, and suggesting otherwise was likely to be taken as a bit of an insult. It was Winter who put forward his suspicions as to why that was (to UDiscoverMusic), saying that he thinks part of the reason was that Zappa knew how hard his music was to play, and simply wanted everyone clear-headed enough to get it right. And that? That led to his anti-hippie stance, too.

Ahmet Zappa said that he had countless people try to reminisce with him and tell stories about Laurel Canyon: Jamming with Zappa, hanging out, pot smoke in the air ... "I'm like, 'Yeah! It never happened. Didn't happen.'" He continued: "So when I'd tell people he didn't do drugs, they'd say, 'How can someone have such a cool imagination without drugs?' which I think is sad."

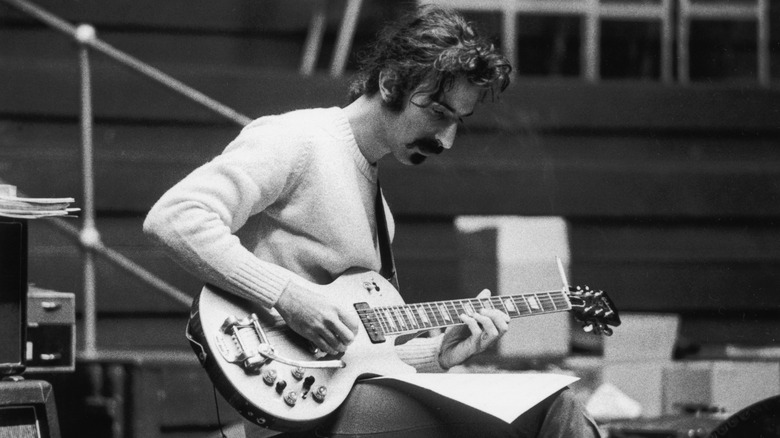

Zappa wasn't as serious as everyone thought

To say that Frank Zappa has a reputation as being a bit prickly is perhaps the understatement of the year. Zappa knew exactly what he wanted to hear from the musicians around him, and when Alex Winter spoke with AllMusic about the things that he learned from sifting through the tons of material Zappa left behind, he said that one of the things that surprised him the most was how collaborative he was — and how accessible he was.

Winter spoke about the idea that Zappa treated musicians as though they were instruments, directing, specifying, and getting them to produce precisely what he had in mind. "But I think that he was actually very collaborative," Winter says. "[W]hile he also had a desire to hear what he had written played well and played properly, but often those artists were bringing more of their own life to it than people recognize."

Winter said, too, that when he was really deep into the footage Zappa left behind, he found that the public persona dropped away. Gone was the guarded, stiff, severe Zappa: "His attitude offstage was often incredibly chill and warm. It may be direct, it may be strict, but in almost all the archival, he [did] come off much warmer than I expected."

His thoughts on modern technology ... via his son

When ABC News spoke with Ahmet Zappa around the release of the Alex Winter documentary "Zappa," they asked him an incredibly interesting question. It was based on his father's well-known, high-profile, and fanatical devotion to speaking on behalf of artists, their right to free speech, and the necessity of not normalizing censorship. They wanted to know: What would Frank Zappa have thought of the internet era?

His answer was twofold: On one hand, he said his father would have loved the idea that the internet gave so many people a platform that they wouldn't have had pre-internet. "I wouldn't have been surprised if he was one of the founders of Google or YouTube and he definitely would have had a platform that celebrated everyone's points of view," Ahmet explained. But he wouldn't have considered it all good news, and he added that his father would have been leading the charge against another behemoth.

"He would have fought mega corporations for taking the value out of music," Ahmet said, and he was betting that his father would have seen things change. "I think we'd have better streaming services and better ways for artists to communicate and make a living."

Zappa had complicated views on success

Part of Frank Zappa's too-cool aura was a disdain for music that, well, wasn't his. In interviews with The San Diego Union-Tribune, he condemned everything from the way people listened to music to what was on the radio when he went to the dentist, saying, "[H]e had his radio tuned to 'The Wave,' and it was nauseating me. I couldn't tolerate it."

There were some things that he approved of — like jazz — but when Alex Winter did a deep-dive into Zappa's work, he tried to answer the question of whether or not he saw commercial success as something to be feared or something that meant what he was putting out wasn't good because it catered to a wide audience.

Winter told AllMusic that he walked away from the project with an interesting take on things, saying: "[H]e wasn't afraid of success, and he wasn't afraid of commercial success, but something in him, I think, was inherently suspicious of his own desire to be writing music for commerce as opposed to what he thought was good art, and his own fear of being swayed toward jeopardizing the quality of his work for agenda," he explained. In other words, it wasn't so much what the music meant to everyone else, but what it meant to him — and a desire "to keep himself honest, as it were."

Joe's Garage

In 2008, the Open Fist Theatre Company staged a production of "Joe's Garage." It was based on the Frank Zappa album originally released in 1979, and it's complicated stuff that takes on everything from religion to the life of a musician. The album was split into acts and billed as a rock opera, and it wasn't until Open Fist's Pat Towne happened to direct Zappa's daughter, Moon Unit, in a play that he got in touch with Gail Zappa and learned that yes, he had always intended on turning it into a stage production, but it was too big and expensive to even think about staging.

So, decades after he had originally written it, it was performed on stage — all the while keeping in mind the fact that in order to truly do it justice, they needed to stay as true to Zappa's vision as they could. The show's producer, Michael Franco, told the Los Angeles Times that they found it eerily relevant: "The idea of government eavesdropping and mandating the behavior of its citizenry? Really, really in play. I think he feared that America would turn into a fascistic theocracy, and, lo and behold, we're awfully close."

Towne also confirmed that no part of it was easy, starting with the fact that there was no score, and someone had to be hired to transcribe the whole thing from the album. Still, he said, "[I]t has to be absolutely right, because it's about the music."