Things About Anime People Get Wrong

Anime has long been considered a bit of a niche fandom. Like many aspects of pop culture that are not "traditional" to Western audiences, it has been met with skepticism and derision over its history. You can see the same pattern throughout the years with everything from fantasy novels to Dungeons and Dragons and LARP, to even something as ubiquitous as using a computer. Things considered the domain of "nerds" are often misunderstood until they become so widespread everyone finally sees what all the fuss was about. Or they at least accept it exists.

Because not everyone is into anime or they've only had experience with a few types of anime that maybe they didn't enjoy, there's a lot of misinformation out there. Imagine if you'd never seen American films before and your first experience was Tommy Wiseau's The Room. You might never give film another chance and be convinced everything else was surely just like that.

You can't really know a thing if you've never experienced it and, for better or worse, humans are quick to rush to judgment on things based on one or two bad experiences. So with that in mind, here are a few things people tend to get wrong about anime.

Anime is older than you think

Most Western audiences of a certain age likely had their first contact with anime with Astro Boy or the 1988 film Akira. Younger audiences obviously came into the fold with powerhouses of anime like Dragonball Z, which got an English-language release in 1996, or Pokemon, which saw both Game Boy games and the anime premiere in North America in 1998. However, what we consider anime in Western culture, which is essentially just animation that originates in Japan, is much older than you think. In fact, anime can be traced back as far as 1917, according to anime expert Frederick Litten.

Oten Shimokawa made a film called Imokawa Muzoku The Doorman in 1917, widely considered the first anime ever created. There's actually an even older anime, though it's not a full film and never had a commercial release, that only features an animation of a boy writing on a blackboard then turning around to salute. That one may be up to 10 years older than Shimokawa's.

Considering the first known work of traditional Western animation, as noted by The Atlantic, is 1908's Fantasmagorie, that puts anime on equal footing and means it essentially grew up right alongside Western animation.

Anime is not just for kids

We have a weird relationship with animation in the world of pop culture. Cartoons have long been considered the purview of children, and not without reason. They're flashy, colorful, and able to show off fantastic and bizarre things that real life can't convey. They're very appealing. But by the same token adults are quick to embrace Pixar animation, for instance. In 2017, Forbes noted that none of Pixar's 18 films had grossed less than $100 million at the box office. Those weren't just kids paying to see those films.

We're able to accept animation as being adult, or at least being able to be enjoyed by both children and adults. Anime is often dismissed as being just kid's stuff, however. That stems in large part from what are considered the most popular animes, things like Dragonball Z and Pokemon, which are very child-friendly.

As the University of Hawaii's campus newspaper Ka Leo pointed out, just because some anime is child-friendly doesn't mean all anime is child-friendly. North American audiences tend to categorize anime as its own genre. But there are romance anime, action anime, comedy anime, and some that are relatively mature, like the very dark Death Note.

It's not all violent

One of the major criticisms lobbed at anime relates to the violence. Some people have questioned whether the violence is necessary or if it actually diminishes the story and medium. It is true that a lot of anime takes advantage of the fact it is not bound by any laws of nature to explore baffling levels of violence and gore. Characters can get shot multiple times, explode in gouts of blood and mutate into the most bizarre, disturbing creations. But is that so different than, say, a Western action movie?

If you only focus on violent anime then of course you'll think anime is violent. However, there are many producers of anime making things like romance and comedy anime that involve little to no action. Dramatic stories like Golden Time or just goofy fun like Polar Bear Cafe eschew fighting in favor of romance or, you know, polar bears that run a cafe. The website Crunchyroll has a massive list of anime available to watch, and the romance section alone features dozens upon dozens of titles, not to mention drama, comedy, and sports among others. Basically you need to look at anime the way you look at any TV — it covers the whole range.

It's not too adult

Ironically, while some look at anime as being too juvenile, others feel the exact opposite. The idea that anime is in some way inappropriate for children because it's obscene is not a new one. It's very true that some anime is extremely adult-oriented. If you've ever done a Google search for anime and run into some adult videos you weren't intending to see, you know this all too well.

But again, this isn't different than regular film. Most obscene anime falls under the banner of hentai. It may feel more disturbing to audiences because it's animated and many of us associate animation with children already. Traditional anime includes dozens of subgenres, but unfortunately, they all get marred together.

Adult-oriented anime is popular, but so are adult-oriented films with real-life actors. You wouldn't show those to kids, and if they're not your thing, you can go ahead and not watch them the way you don't watch all the other stuff you don't like.

There's no concise definition of what anime even is

If someone says "I don't like anime," there's potentially a lot more to unpack in that statement than you might think. First and foremost, what do they mean by "anime?" The word literally just refers to animation, and Western audiences use it as a blanket term for animation from Japan. But there's no strict definition of what anime really is.

Anime expert Jonathan Clements gave a talk at AnimeFest in 2015 about popular misconceptions regarding the medium and noted that a Japanese book published in 2011 on anime studies spent 100 pages arguing over exactly what anime was. That's one reason it's difficult to address anime criticisms — they're too wide-ranging. Is it anime for children, violent anime, adult anime, romantic anime, low-budget, television, film, or something else altogether? "Animation from Japan" is just too wide a net to cast when trying to discuss something with such a long history and such a diverse amount of content.

When you try to factor in animation from Korea or China, or maybe animation made in North America but in a style that emulates traditional anime, are those things still anime? There are a lot of questions to ask, but not a lot of solid answers.

Anime fans aren't weird or losers

Any fandom is likely going to have its detractors — just look at soccer. It's arguably the most popular sport in the world, but people who don't enjoy it still rip it apart pretty routinely. The same thing happens with anything from Star Wars movies to Nickelback to Stephen King books. So maybe it's no surprise that, despite anime's popularity, detractors will often criticize not just the thing itself but its fanbase. Fans of anime, as with fans of many things in nerd culture, are often derided as "weird" or "losers."

The thing about anime fandom is it's very diverse. In fact, a number of celebrities have professed to being big anime fans. Everyone from Keanu Reeves, who played John Wick and was once attached to a Cowboy Bebop movie, to Samuel L. Jackson, who has lent his voice talent to Afro Samurai. MMA star Ronda Rousey has even gone on record with her love for Dragonball Z's Vegeta, while the late, great Robin Williams was known to be a huge Neon Genesis Evangelion fan. Just goes to show the world of anime appeals to all kinds of people.

Anime is not cheap and low quality

One of the earliest animes experienced by Western audiences was Astro Boy. Osamu Tezuka, considered by many to be the father of anime, created the show in the 1960s and used an incredibly bold animation method to sell the show — he cheaped out on it. While traditional animation was around 24 frames per second, Astro Boy was running at a very reduced 10 frames per second. Tezuka also had a bank of image frames that could be reused and recombined again and again for new scenes, according to one fan website. This meant that, to audiences with a discerning eye, anime came across looking a little stilted, repetitive, and cheap. Toss in a very long opening theme song that was repeated every episode, and a very long closing credit sequence, and you only needed to make maybe 15 minutes' worth of cartoon per 30-minute show.

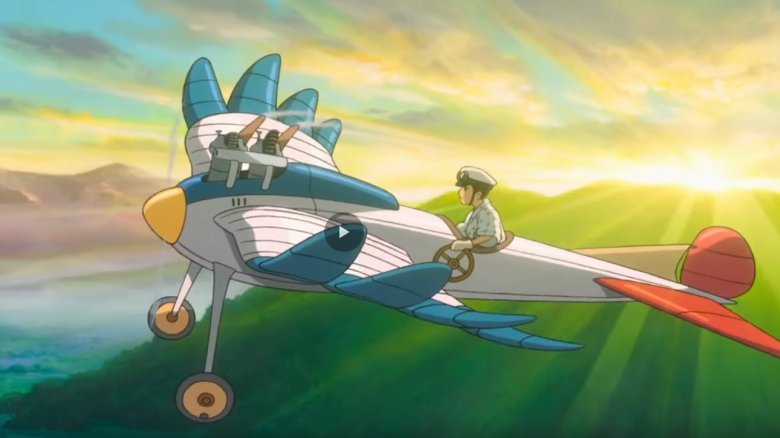

While some anime relied on the Tezuka method to produce numerous episodes on the cheap, the breadth of anime means one example of low-cost filmmaking doesn't really represent the whole. Compare a low-budget movie on SyFy with something like Avatar – it's apples and oranges. Which is why some anime like Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away can look so remarkably different — that movie was made on a $19 million budget. Steamboy holds the record for most expensive anime ever at $20 million. So sure, some can be cheap, but just like Hollywood, some properties break the bank.

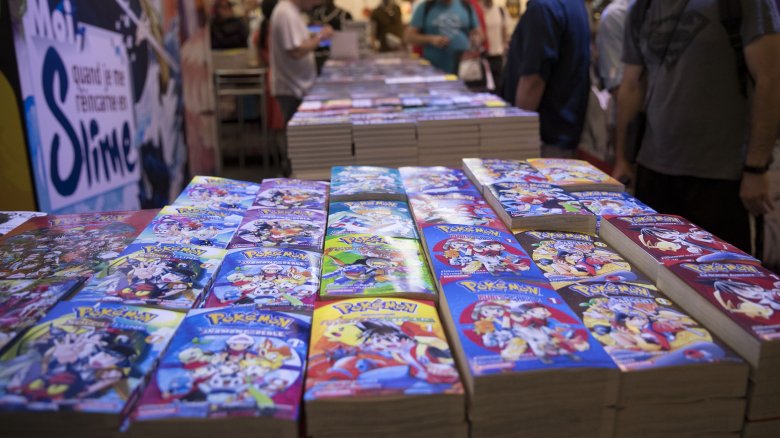

Anime is animated while manga are books

Terminology can be a tricky thing in any industry. If you've ever listened to a group of doctors or nurses trying to explain something to each other while they toss out medical jargon, it can be a little overwhelming to the untrained ear. Similarly, what seems obvious to someone who's deeply immersed in the anime culture may as well be ancient Greek to an outsider being exposed to it for the first time. It's made worse because some terms are used interchangeably when they really shouldn't be.

Though it seems obvious, the word "anime" refers exclusively to animation. Anything not animated really can't be anime. If it's in a book, it's manga. Even if it's a book about a popular anime, it's now the manga of that anime. If the anime came from a book, then the reverse is true — it's the anime adaptation of manga.

Another point of contention is how you refer to anime for a general audience and anime that is strictly adult. The adult stuff is something else entirely, and it's definitely not the same thing, so you need to be careful with what you're Googling.

A lot of anime is very niche

Most people only know anime as that action-packed stuff that, whether intended for kids or adults, seems to be cranked up to 11 and is way over the top. Usually there's a sci-fi element, maybe monsters, but you better believe someone is getting seriously beat up with a lot of flashing lights and yelling. What many people don't realize is just how niche anime can get. There is literally an anime for everyone, whether they know it or not. Some of it is so niche you might be hard pressed to find any casual fans of it at all, but they're out there.

Extremely niche animes range from things like Superbook, which is an anime adaptation of Bible stories, to Onara Gorou, which is about an actual fart. For history buffs, there's even propaganda anime from the 1930s including one in which a sinister Mickey Mouse attacks Japan. There's even one called She and Her Cat about a young woman growing up and branching out on her own in life, as seen entirely from her pet cat's perspective.

Yes, there are really mainstream anime genres out there, but if you have any kind of obscure interest at all, there's a good chance someone's covered it in an anime.

It's not poorly written

One of the easiest ways people will dismiss something is by calling it stupid or lazy. It's a catchall insult that really doesn't mean much, and it's been levied against anime since it first showed up. It's also pretty relative. What qualifies as stupid to one person wouldn't be so dumb to someone else. Objectively speaking, however, anime has been lauded more than once for its powerful storytelling and exceptional imagery.

One of the foremost anime filmmakers in the world is Hayao Miyazaki. His films include Princess Mononoke, Kiki's Delivery Service, and Howl's Moving Castle. His 2001 epic Spirited Away ended up being the highest-grossing film in Japanese history, according to the Wall Street Journal. More than that, however, Spirited Away is critically acclaimed with an incredible 97 percent on Rotten Tomatoes and it took the Academy Award for best animated feature in 2003.

Howl's Moving Castle was nominated in 2006, and The Wind Rises was nominated in 2014. Other anime features such as When Marnie Was There and The Tale of Princess Kaguya have also received nods. The fact is, anime can and does deliver some very exceptional storytelling — perhaps people just need to be open to experiencing it.

Anime doesn't cause seizures

One of the most infamous American tales was from 1997 when word got around that children watching Pokemon in Japan had suffered seizures. As the story went, the flashing lights triggered seizures and other illnesses in as many as 12,000 children. The Simpsons even used an episode to send the Simpsons to Japan and fall victim to a seizure-inducing action cartoon. While it's true that quickly flashing lights have the ability to trigger epileptic seizures, did it actually happen?

According to Live Science, despite how popular that story was, it doesn't hold up to scrutiny. The diagnosis was not Pokemon-induced seizures but mass hysteria. Symptoms of dizziness, headaches, and vomiting didn't track with seizures, while actual seizure symptoms like drooling, tongue-biting, and stiffness were nearly nonexistent. What actually happened was that some children reacted to the show, and then the next day after the story got out, 10,000 more cases suddenly appeared. It was only after the media covered those few initial incidents that everyone else jumped on the Pikachu Pox bandwagon.

It's possible some children had legit seizures (about 1 in 5,000 people suffers photosensitive epilepsy), but it just wouldn't be that many kids.

Anime is still a thing?

You ever notice how older people seem out of touch with what the kids are into? No matter how old you are, there's a good chance you don't fully know what the people 10 or 15 years younger than you are obsessing over. Whether it's music, games, or popular slang, you tend to lose track because you're just not part of that world. When you do hear about something, it's only after it got really big. So when anime got big, people heard about Pokemon. And that stayed in their heads, even years later. Now, so many years later, when someone says anime, those same people think "Oh man, is that still a thing? Didn't Pokemon come out in the '90s?"

Anime's popularity has actually been growing pretty steadily since the 1990s and the Pokemon revolution. Revenue for Japanese animation grew every year from 2009 to 2016, according to the Association of Japanese Animations. It's extremely popular in numerous markets, including China, Korea, and of course the United States. In fact, the global anime market was worth over $7 billion in 2016 alone. So yes, it's very much still a thing and is increasingly more a thing each and every year.