The Last Kings And Queens Of Europe

A quick look at the history of pretty much any European country — past or present — suggests that monarchs and dynasties come and go, but the countries more or less remain. Sometimes, in cases of conquest, the monarchy disappears completely, to be replaced by another state. In other cases, the monarchy is replaced by a republican form of government.

Europe's monarchies are often thought of as decadent relics, but until around 70 years ago, they were the continent's rulers. Due to constant intermarriage, most of Europe's last kings and queens were descended from its greatest dynasties. Yet, many were mere shadows of the great men and women who preceded them. In keeping with this theme, many chose exile over death. But one or two, despite their powerlessness, chose to go out swinging rather than live out the remainder of their lives far from home.

Europe — particularly since the end of World War II — has seen its monarchies fall one after the other. From a continent once dominated by crowned sovereigns, there are only a handful of them left, mostly in Northern Europe and Spain. Here's how some of Europe's last reigning monarchs were overthrown and where they ended up.

Sultan Muhammad XII of Granada

Muslim Spain lasted nearly 800 years after Arab armies conquered most of the Iberian peninsula in the early eighth century. But its last centuries were spent fighting for survival against steady Christian pressure from the north. As the Muslim kingdoms fell one by one, only the Nasrid Sultanate of Granada remained in 1491.

By then, Granada was a shadow. Sultan Muhammad XII (aka Boabdil) had inauspiciously come to the throne by overthrowing his father in 1482. Unfortunately for him, he became a prisoner of war of the powerful Kingdom of Castile, only gaining his freedom by ceding virtually his entire kingdom held by his father and other disloyal subjects, leaving only Granada itself. Soon, Castilian Queen Isabella and Aragonese King Ferdinand decided they wanted that too.

The Catholic monarchs laid siege to Granada in 1491. Faced with a no-win situation, Muhammad chose to surrender the city and avoid a bloody assault. None other than Christopher Columbus – an eyewitness to the events — recorded in his journals that the Nasrid sultan was forced to pay homage to his conquerors and watch in humiliation as his family's banner came down. Per Granada Hoy, legend has it that as Muhammad and his court filed out of the city for North African exile, he looked back at his home, sighed, and began to cry. His mother — the driving force behind much of his misfortune — is said to have replied in disgust, "Cry as a woman [for] what you have not known how to defend as a man."

Constantine XI Palaiologos of the Byzantine Empire

In 1452, the once-great Byzantine Empire was in a sorry state, controlling little more than the city of Constantinople. The following year, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II laid siege to the city to finally capture the jewel of Christendom that had eluded so many other Muslim rulers.

Facing Mehmed and his massive army was a 10,000-strong force of defenders under Constantine XI Palaiologos. Despite the nearly impossible odds, the last Byzantine emperor decided to go down fighting rather than flee the city for a European exile. The defenders gave the Ottomans a heroic struggle, but were eventually thrown back when Mehmed's forces breached the walls. In the chaos of the street fighting, Constantine realized the game was up and rallied his remaining men for a final charge. After he urged them to place "all hope in the irresistible glory of God," the defenders fought to the death.

In the vicious fighting that followed, Constantinople fell — a monumental event that would lead to the Renaissance. Constantine disappeared without a trace, but most likely died in battle. But that did not stop legends about his fate from arising after the siege. The most famous, per the Greek Reporter, is that the emperor turned to stone out of sadness at seeing his city and empire laid waste. Some eagerly await his return, hoping to one day see the city restored to Christianity. Today, the emperor is considered a hero in Greece and an unofficial saint in the Orthodox and Greek-Catholic churches.

Stjepan Tomašević of Bosnia

King Stjepan Tomašević was the last ruler of an independent Bosnia. Another victim of Ottoman aggression, he did not go down in a blaze of glory fighting to the death. He came to the throne in 1461, succeeding his father Tomas, per the Cambridge Medieval History.

When Stjepan was crowned in a lavish ceremony, he claimed to rule Bosnia, the Dalmatian coast, Serbia, and Croatia, even though in practice, he controlled none of these. In fact, he had to beg the pope, the Venetians, and the Hungarians to protect him. The Hungarians were willing to defend Bosnia — a territory they had designs on — if King Stjepan stopped paying protection money to the Turkish Sultan Mehmed II. Naturally, Mehmed was none too pleased and promptly prepared to invade Bosnia. Stjepan quickly begged the sultan for forgiveness and secured 15 years of peace — or so he thought.

It turned out that Mehmed had deceived him. The sultan invaded Bosnia anyway as the kingdom's defenses were down, capturing Bosnia's three major fortresses and eventually Stjepan himself. For Stejpan, the humiliation did not end with his execution alongside his uncle and brother. His wife, Bosnia's ex-queen, was enslaved to an Ottoman official, while the rest of his family fled to the Italo-Dalmatian city of Ragusa. Meanwhile, Stjepan's erstwhile Hungarian allies occupied the northern part of his kingdom, while the Ottomans took the rest.

Stanisław II August Poniatowski of Poland

In 1764, Poland elected its last king, a nobleman and diplomat named Stanisław II August Poniatowski. He also had the distinction of having been Catherine the Great's lover. Catherine had by now become Poland's biggest antagonist, and she perhaps believed him pliable and amenable to her influence thanks to their liaison years before. But Stanisław intended to keep Poland alive. Despite his best efforts, problems began in 1768, when a civil war allowed Poland's much-larger neighbors — Austria, Russia, and Prussia — to pounce and force Poland to surrender a third of its territory under the First Partition in 1772. Undeterred, Stanisław continued with internal reforms, embracing new, dangerous ideas that his neighbors did not like.

King Stanisław had imbibed Enlightenment ideas, including constitutionalism. On May 3, 1791, Poland ratified a constitution, which he mostly wrote, introducing among other things the idea of equal Polish citizenship to the population, regardless of rank, religion, or ethnicity. The Polish nobility opposed the changes and rebelled, allowing Russia and Prussia to opportunistically annex more Polish territory in 1793.

But Poland would not go down without a fight, taking inspiration from none other than the United States. In 1793, cavalry officer and American Revolutionary War veteran Tadeusz Kościuszko rebelled against the partition, leading a resistance that was put down in 1794. Faced with a broken, devastated country and with no further path of resistance, Stanisław abdicated his throne in 1795, leaving Austria, Prussia, and Russia to divide what was left of his battered kingdom.

Francesco II of the Two Sicilies

Francesco II, last Bourbon king of the Two Sicilies, was by all accounts a good man. The Bourbon family website describes him as a devout man with a sincere sense of duty to God, country, and his people. He came to the throne in 1859 at the tender age of 23, schooled mostly in religious matters rather than matters of state. Nevertheless, the young king threw himself into his work, reforming the kingdom to bring relief to the poor and encourage economic growth — mostly by lowering taxes and granting greater local autonomy over economic affairs. But in 1861, it all came crashing down.

Francesco came to power at a time when the northern Kingdom of Sardinia was unifying Italy. The Two Sicilies stood in the way. So Giuseppe Garibaldi, best known as Italy's founding patriot, invaded Sicily with 1,000 men with the help of members of the Two Sicilies' army and nobility, who disliked Francesco, per L'enciclopedia Treccani. Eventually, they holed up the king and his army in the fortress of Gaeta north of Naples, where they eventually surrendered in 1861.

The king and his wife went into exile, first in Rome and then later in France. Before leaving, the king donated much of his money to help victims of an eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The consequences of the fall of the Two Sicilies were immense. After the kingdom's fall, land reform and the ravages of war sent millions fleeing to America in search of a better life.

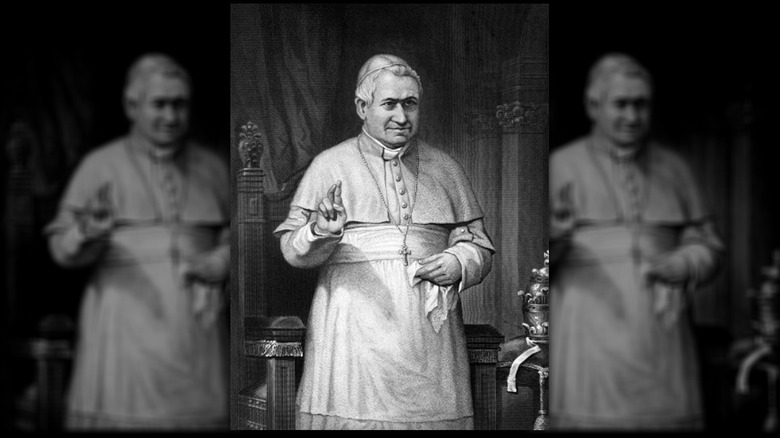

Pope Pius IX of the Papal States

As the unification of Italy accelerated in the 1860s, one central Italian ruler saw his kingdom reduced to nothing: Pope Pius IX. The pontiff was not only the head of the Catholic Church; he also ruled over a kingdom called the Papal States in Central Italy.

The Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed in 1861, had declared Rome its capital that same year. But the city was still under papal rule, which was backed by the presence of French troops whom Italy did not want to fight. Matters changed in 1870 when Napoleon III pulled his troops from Rome to defend France's eastern border against a resurgent Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War. Italian General Raffaele Cadorna promptly attacked Rome with 50,000 men. With only 13,000 men of his own, the pope surrendered the city and with it, his kingdom.

With the capture of Rome, Pope Pius became a "prisoner within the Vatican," per EWTN. But he was still the head of the Catholic Church, so he couldn't simply be gotten rid of. From his "prison" in the Vatican, he continued to oppose anti-Catholicism everywhere, whether by Napoleon III of France, the Italian government, or Germany's Otto von Bismarck. But he would not live to rule a new state of his own. That would have to wait until the 1929 Lateran Treaty, when Benito Mussolini and Pope Pius XII created the Holy See and ended the Italo-Papal feud once and for all.

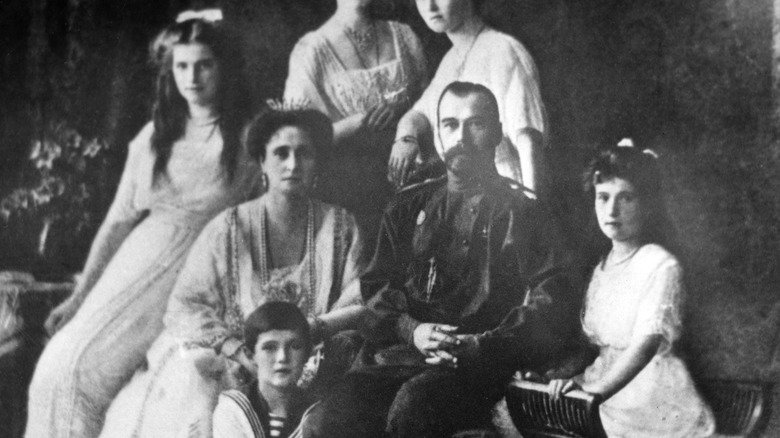

Czar Nicholas II of Russia

The last czar of Russia, Nicholas II, met what was probably the most brutal fate of all the rulers on this list. Now, Nicholas was no tyrant. Per the Alexander Palace Museum, he was actually a dedicated ruler and devoted family man — even though he did not love being emperor. Yet, he met a bloody end when the communist Bolsheviks staged their Revolution in 1917. Among their first actions was to imprison the imperial family, who eventually ended up in the Ural city of Yekaterinburg, where they were murdered.

The grisly details come from the firsthand account of Bolshevik executioner Yakov Yurovksy. He testified to personally lining up the czar and his family, pronouncing a hasty death sentence on them, and shooting Nicholas dead. The soldiers indiscriminately shot the rest of the family, including 13-year-old crown prince Alexei. The women, however, would not die, whether from bullets or bayonet. It turned out that they had sewn their jewels into their clothes, which served as armor. So the executioners shot the czar's four daughters and Empress Alexandra in the head. They then buried the bodies in a nearby forest.

Nicholas and his family became martyrs of Christendom, particularly in the Orthodox world. According to Holy Transfiguration Orthodox Church, the Russian Metropolitan Makary had a vision of Nicholas in heaven with Christ. The czar had sacrificed himself to expiate Russia's sins — or so the story went. In 1998, the czar and his family were properly laid to rest at the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg.

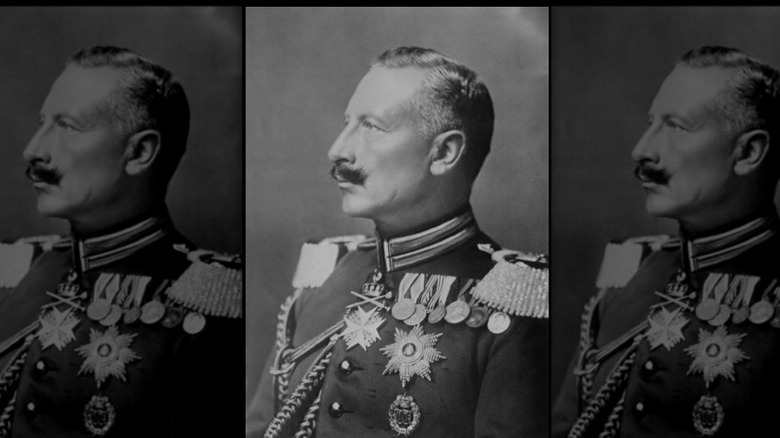

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany

Kaiser Wilhelm II was yet another European monarch to lose his throne after World War I, although he did not suffer the same brutal fate as his cousin Nicholas II. Kaiser Wilhelm delivered his abdication in 1918, and went into exile in the Netherlands.

The kaiser left his own account explaining his side of the abdication. In his abdication letter to his son, he argued that although he wanted to lead the German army himself in its final offensive westward, he noted that his country had been split in two, with two governments fighting over power in Berlin. Further he mentioned that the soldiers were "no longer trustworthy," a likely reference to the backed German Revolution mentioned in his son's letter to Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg.

In 1922, the kaiser wrote a retrospective account elaborating on his abdication. First of all, he wrote that in part his hand was forced. Troops on the Rhine front in the West had mutinied and Germany needed an armistice at all costs to end the fighting. Here, Wilhelm painted himself as a martyr of sorts. Instead of taking loyal soldiers and engaging the rebels, he figured it best to abdicate and spare his people a civil war and obtain a just peace for Germany. As the kaiser lamented, Germany got neither, descending into a period of intense unrest marked by two back-to-back uprisings — a situation that was made worse by the Treaty of Versailles and the massive indemnity the country was expected to pay.

Mehmed VI Vahideddin of the Ottoman Empire

Sultan Mehmed VI Vahideddin of the Ottoman Empire ruled what had once been one of the world's foremost Islamic empires. By 1922, however, the mighty had fallen indeed. The sultan attempted to govern what was left of the Ottoman Empire, which had been reduced to Turkey itself after the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. But he faced the problem of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's nationalists, who had installed themselves as Turkey's rulers in Ankara.

The nationalists eventually wrested control of Turkey and abolished the Ottoman Empire in November of 1922. Per Turkish writer Kaya Genç for New Lines Magazine, Mehmed and his son fled Istanbul on a British ship under the cover of darkness, headed for Malta. Atatürk's government banned all members of the imperial house from entering Turkey, and thus, the sultan never again returned to his native land.

Like many on this list, the sultan met a sad, ignominious end in exile. He lived in Italy at the pleasure of Benito Mussolini. But he lived in fear of assassination and struggled financially for the rest of his life. He was so deeply indebted when he died in 1926, that the Italian authorities even held his coffin as collateral. His daughter eventually came up with enough money to give her father a modest burial in Damascus, far away from his beloved Istanbul.

King Zog of Albania

Albania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1912 with the Vlorë proclamation, amid the chaos that engulfed the Balkans shortly before World War I. But the country was chronically unstable through World War I and the 1920s. Among the prominent regulars of Albanian politics was Ahmed Bey Zogolli. The son of Albanian nobility, he invaded the country from exile in Yugoslavia, seized the presidency, and liquidated his opponents. He realized, however, that he needed a powerful foreign backer to guarantee his position.

Zogolli turned to Benito Mussolini's Italy, striking an alliance in 1927 in hopes that Italian investment and aid would allow Albania's rural and medieval economy to modernize quickly. With Italian support, he ditched the republican title of president and decided to become King Zog I. He was crowned in the Albanian parliament, swearing on both the Bible and the Quran to keep Albania independent and united. Thus, he became Europe's first and only modern, native Islamic monarch.

Unfortunately for Zog, his tenure as king only lasted 11 years. By the 1930s, Mussolini had begun demanding ever-greater control over Albania's resources in return for continued Italian support. Furthermore, Albania was running massive trade deficits with Italy, becoming completely reliant on Italian money and imports to survive. Despite the situation, Zog refused to hand over his country to Mussolini. Italian forces invaded in 1939, forcing the king and his family to flee to London. He died in Paris in 1961.

King Simeon II of Bulgaria

King Simeon II of Bulgaria can appropriately be called Europe's comeback kid — literally. According to the Vrana Palace Museum, the king, who was born in 1937, found himself on the Bulgarian throne at the mere age of 6, in the middle of World War II. During his first year, a regency council exercised power on Simeon's behalf. But in 1944, Bulgarian communists backed by Soviet tanks seized power, overthrew the regency council, and executed its members — Simeon's trusted advisors. The young king was left isolated and surrounded by communists, who formed a new regency council that eventually abolished the monarchy in 1946.

Simeon lived first in Alexandria, mixing with the exiled Italian royal family and King Zog I of Albania, in Spain, and then in the United States, where he attended the Valley Forge Military Academy. Alongside his career in banking and finance, he worked with anti-communists to bring about an end to the ideology in his homeland. In 1996 — seven years after the fall of the Iron Curtain — he finally returned home.

Now, his return home might have been Simeon's happily-ever-after, but the ex-king had made a vow in 1955 as an 18-year-old to return to his country as a public servant. Thus, he went into politics and was so successful that he got himself elected Bulgaria's prime minister in 2001. Thus far, he remains the only European royal to have made a political power comeback after losing his throne.