Ganymede: The Solar System's Mightiest Moon

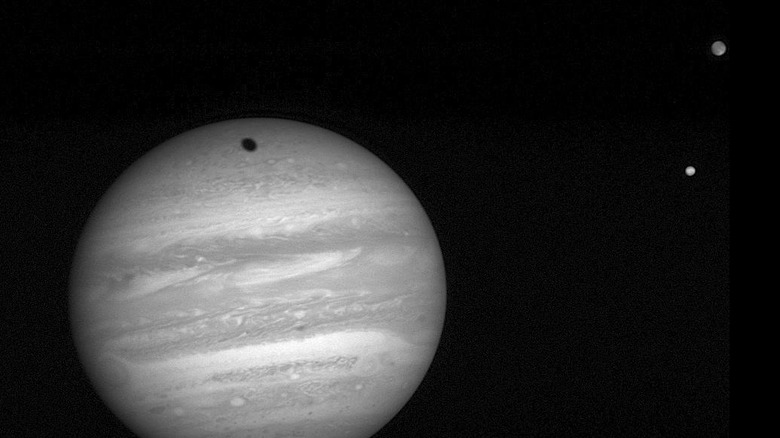

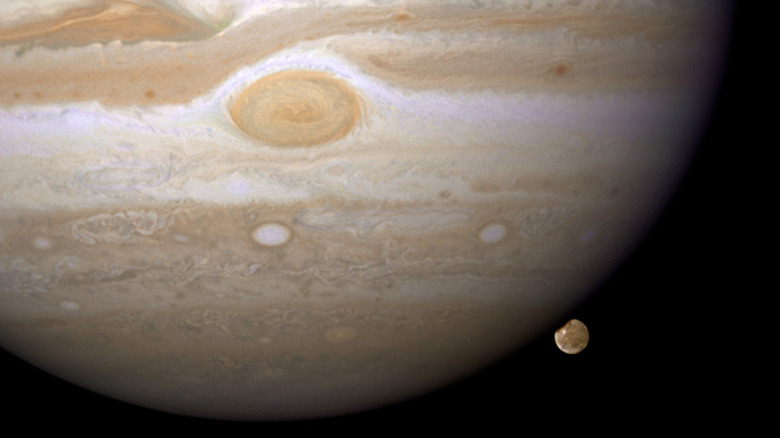

Jupiter's moon Ganymede is virtually a planet in its own right. Not only is this distant world the largest of the solar system's moons, but it's also even larger than the planet Mercury. Ganymede has captured the imaginations of people on Earth for decades, making it a popular setting for science fiction, from a novel by Robert A. Heinlein to the anime series Cowboy Bebop. But, hiding oceans of water and a host of secrets, the truth of Ganymede may just be even more exciting than fiction.

Ganymede was officially discovered in 1610 by the Italian astronomer Galileo. There's a possibility though, that it may first have been observed far earlier. The "Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures" mentions an ancient Chinese astronomer, Gan De, whose accounts suggest he may have spotted the moon as early as 365 B.C.E. In his writings, he mentions seeing a "small reddish star" in "an alliance" with Jupiter. Remarkably, De made his observations without using a telescope; while Ganymede is theoretically bright enough to be seen with the naked eye, it's usually outshone by Jupiter. De, evidently, had exceptional eyesight.

In April 2023, ESA launched a spacecraft to Jupiter. Named the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice), Ganymede is both the primary target and final destination of its 500 million-mile journey. Once it arrives, it will give humanity a much closer look at this fascinating little world.

A planet-sized moon with light footsteps

If Ganymede was orbiting the sun instead of Jupiter, it would almost certainly be considered a true planet for several reasons. A major one is its size. It has a diameter of 3,270 miles, making it about 8% larger than Mercury's 3,032-mile diameter. The planet which gets the most attention as a destination for spacecraft and robotic explorers is Mars and, with its diameter of 4,212 miles, Ganymede isn't too much smaller. An impressive size, considering it's a moon!

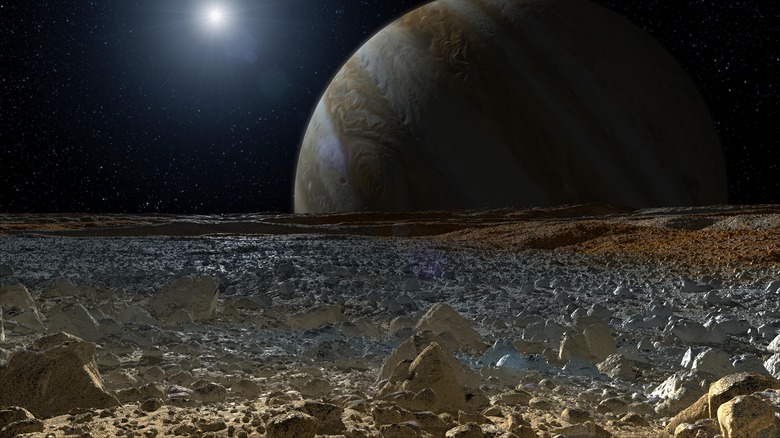

The big difference between Ganymede and the inner planets though, is that it's dramatically less dense than either Mercury or Mars. Like its neighboring moon Europa, a huge amount of Ganymede's bulk is water and ice. The result is that its surface gravity is a lot lower than its large diameter might suggest. Stepping onto Ganymede with its low gravity would feel very similar to walking on Earth's moon. In fact, being mostly made of rock, our moon actually has slightly higher surface gravity than Ganymede. Of course though, with Jupiter and its many moons hanging in the sky, the view from Ganymede would be far more spectacular.

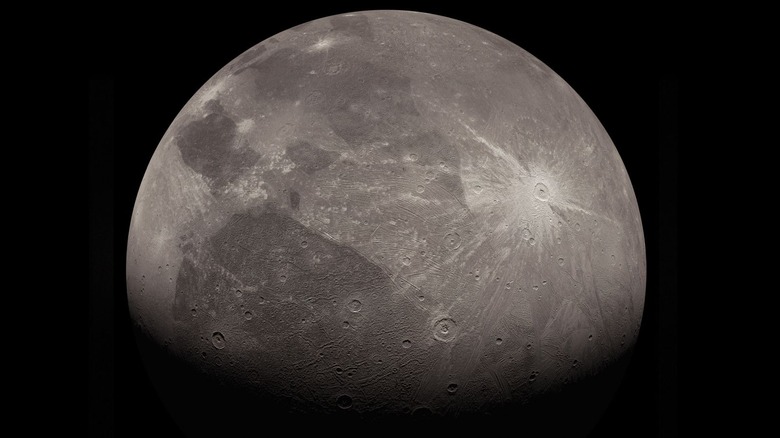

[Featured image by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill via Flickr | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.0]

One day a week

Ganymede rotates a lot more slowly than Earth. A single day there lasts a little over a week back here on Earth. The reason why Ganymede's days are so slow is that it's tidally locked to Jupiter. Just like Earth's moon, the same side of Ganymede is constantly gazing at its parent planet, while its other side always faces away. In other words, a day on Ganymede coincides with its orbit. In Ganymede's sky, Jupiter is a permanent fixture that never moves from its one spot.

Tidal locking happens with any moon orbiting its planet closely enough. When the gravitational forces on a moon are strong enough, the closer side feels a stronger pull than the side facing outward. The difference in gravitational pull causes the moon's rotation to slow until it synchronizes so that it completes only one spin per orbit. But tidal locking isn't perfect, and a moon in this situation often rocks slightly back and forth on its axis, in an orbital quirk called libration. Earth's moon rocks this way, meaning that over the course of a month, slightly more than half of its surface can be seen from down here on Earth's surface. Ganymede also seems to librate (oscillate) as it orbits Jupiter. According to a study published in the journal Geosciences, one of the Juice spacecraft's many tasks when it arrives is to use lasers to accurately measure Ganymede's libration to find out both how much and how quickly it rocks.

The iron heart of Ganymede

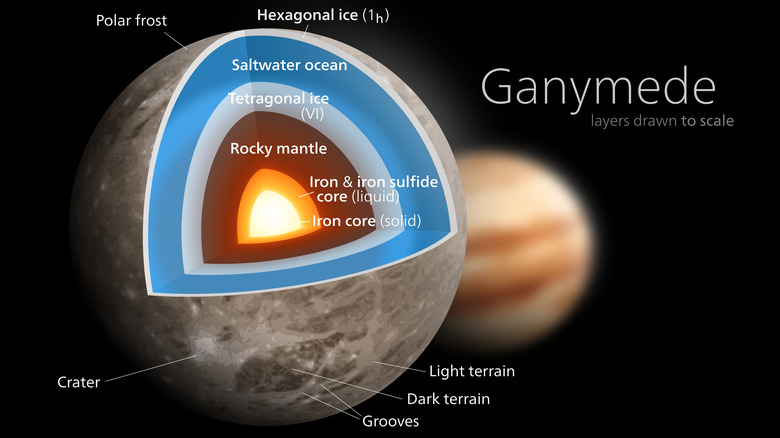

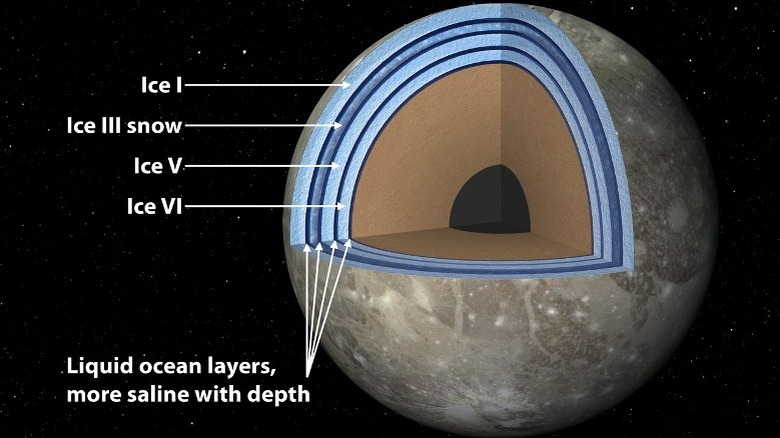

On the inside, Ganymede is surprisingly Earth-like. Deep below the surface, our planet is separated into several different layers of distinct material. When the planet was still young and hadn't finished cooling, heavier matter sank deeper into the center, which is why Earth has a core made of iron. Per an article published in Nature, this trait is shared by Ganymede. Jupiter's largest moon is also differentiated in this way. If you could slice it in half, you'd find several layers with their own separate compositions.

Ganymede's core is made of iron, just like the cores of true planets like Earth. Some planetary scientists suspect that the core of Ganymede may even be molten. Seemingly, Jupiter's largest moon shares more in common with Earth than we might think. The only way to be certain about this, though, is to take a closer look with specialized instruments. This is another of the things that ESA's Juice spacecraft aims to find out more about. When it arrives at Ganymede, learning more about the moon's core is one of its main science goals.

[Featured image by Kelvinsong via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

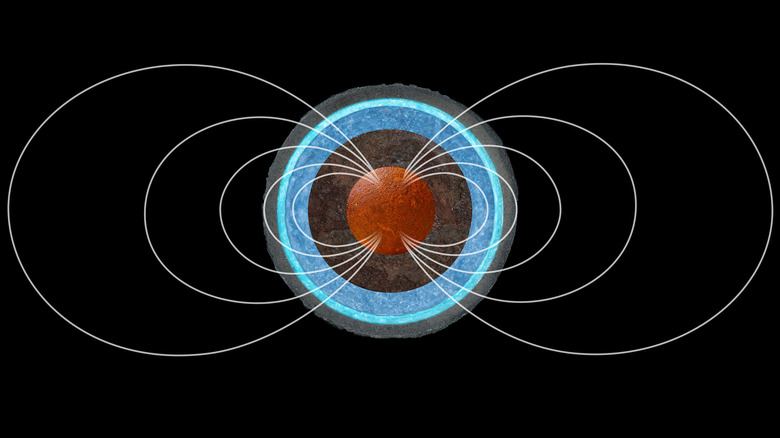

A magnetic moon

Earth's iron core is what generates our planet's magnetic field, protecting its surface — and us — from damaging cosmic radiation. Because Ganymede also has an iron core, it too has a magnetic field. In fact, as NASA explains, it's the only moon in the solar system to have a magnetic field like a planet does. Ganymede's field is most likely generated by its core, but some observations suggest something else in the moon which affects its magnetism. Saltwater. Observations of Ganymede's magnetic field suggest that it could be hiding a vast amount of liquid water under its surface, influencing the shape of its magnetic field.

Unlike Earth though, Ganymede's magnetic field is quite weak. Even at its strongest, it's still weaker than the flimsy magnetic field of Mars. In turn, Mars has a magnetic field about 40 times weaker than Earth's. While Earth's magnetism keeps its surface shielded, Ganymede's magnetic field is seemingly far too weak to offer the same kind of comfort. It likely wouldn't do much to protect any future space travelers who might land there. But then, that probably wouldn't make much difference anyway. Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, has an exceptionally strong magnetic field. Ganymede's orbit is well within Jupiter's influence, meaning that its faint field is like a drop in a magnetic ocean.

[Featured image by NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI) | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

A whisper of atmosphere

At first glance, you might not think Ganymede has much of an atmosphere, but that isn't entirely true. It certainly lacks the familiar hazy shine of reflected sunlight that wraps planets like Earth and Mars but it isn't entirely airless either. But, per NASA, what atmosphere Ganymede does have is incredibly thin. And perhaps surprisingly, it's mostly made of oxygen.

The oxygen in Ganymede's faint atmosphere seemingly comes from water molecules. Being a cold little world, Ganymede's surface is full of ice. It's also being constantly struck by radiation — charged particles which plow into Ganymede's frosty terrain, flinging water molecules off its surface and splitting them apart into hydrogen and oxygen. Some of this water makes it into Ganymede's tenuous atmosphere intact too, albeit by a different process. Where the oxygen is created by energetic radiation, the water vapor gets there through sublimation as solid ice evaporates directly. This is thought to happen on parts of the moon's surface that are warmed by sunlight.

Some more evidence can be seen in the form of ozone. On Earth, ozone is formed in Earth's atmosphere, created as ultraviolet light from the sun tears oxygen molecules apart, making them stick back together in groups of three atoms. While Earth's ozone forms a layer high in the atmosphere, on Ganymede it falls back down to the surface, where it was detected.

[Featured image by NASA, ESA, and E. Karkoschka (University of Arizona) | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

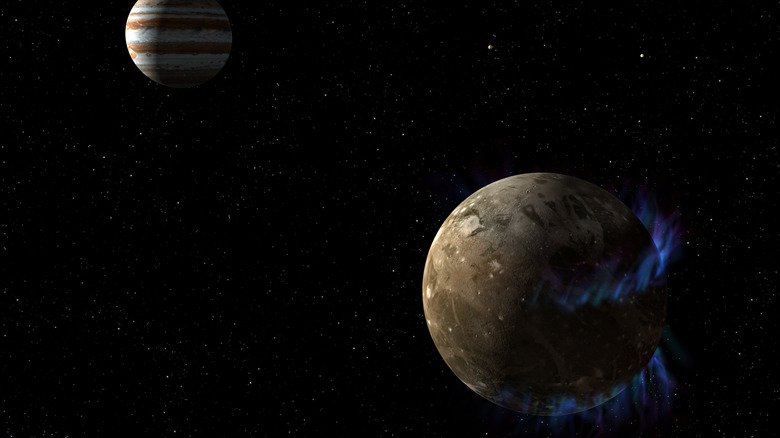

Aurorae in distant skies

With both a magnetic field and a thin atmosphere, Ganymede is the first moon to have aurorae detected in its skies. Aurorae are caused by space weather, as energetic particles fall down magnetic field lines and collide with atmospheric molecules, making them emit light. On Ganymede, the aurorae are caused by interactions between the magnetic fields of Ganymede and Jupiter. Unlike on Earth though, Ganymede's aurorae don't hang over the moon's poles but closer to the equator, near its tropical regions.

The light emitted by Ganymede's aurorae is also in the visible range. As Keck Observatory explains, it's very similar to the green aurorae seen here on Earth, caused by oxygen molecules. The much lower pressure of Ganymede's atmosphere, though, means that Ganymede is less likely to have the bright green of Earth's aurorae. Instead, the glow in Ganymede's skies would most likely be a deep red color, with an undertone of infrared. It's uncertain whether any future spacefarers would be able to see the aurorae on Ganymede with their own eyes though. The atmosphere may be too thin for much to be easily visible, and human eyes aren't very good at seeing red colors in dim light anyway. With cameras though, this moon's dark skies are probably well-lit. A lot of the light from Ganymede's aurorae is also visible in the ultraviolet.

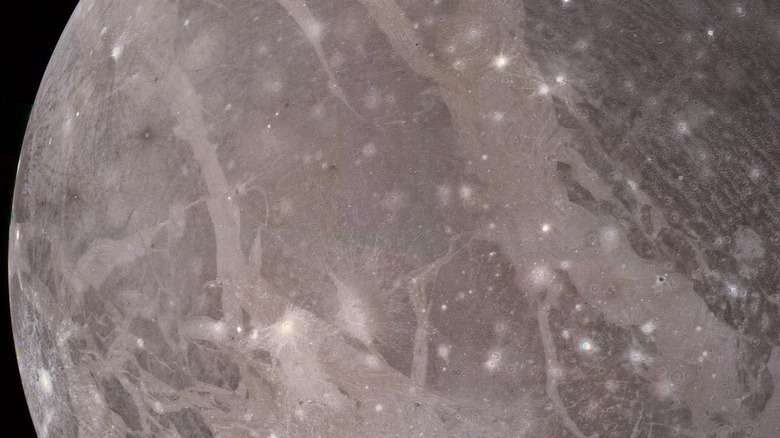

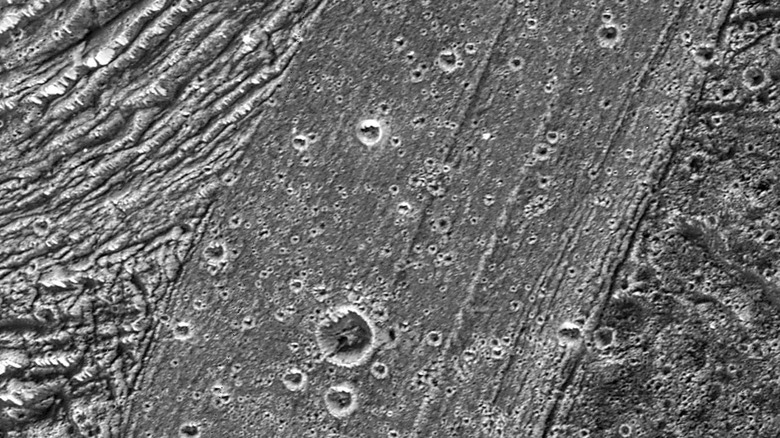

A world of ice and rock

The outer solar system is littered with icy objects. Dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris, and moons like Titan and Europa are all full of ice. Ganymede is no exception to this rule. It may look like it has the same kind of rocky surface as Earth's moon, but Ganymede's surface is mostly made of ice. Water ice makes up at least 50% and perhaps up to 90% of the large moon's surface and crust. Because Ganymede's surface is so frosty, the craters there are noticeably different from those on planets like Mercury too, with ice flowing differently when struck by meteorites.

Ganymede's crust seems to be quite lumpy though. Beneath the surface, scientists at NASA have spotted irregular clumps which could be rock formations trapped in the ice. Here and there, inside Ganymede's icy shell, are dense knots of material, and it's hard to say exactly what they are. There doesn't seem to be even the slightest hint on the moon's surface to explain them. They could be huge chunks of rock, supported by the ice. Another explanation though, could be that they're parts of larger rock formations that extend deeper under Ganymede's surface. Perhaps these could even be the summits of mountains of rock buried under the frigid outer layers of Ganymede's crust. Without taking a closer look at the distant moon, it's difficult to be certain.

Ganymede's overlooked ocean

Ganymede's sister moon Europa is famous as a place where scientists expect to find plentiful amounts of liquid water. With all the buzz surrounding Europa's water though, Ganymede is often overlooked as another potential water world, and there's a good chance that Ganymede too contains a vast subsurface ocean. While all eyes have remained mostly on Europa, scientists have long suspected that Ganymede might also contain a secret ocean. Its presence has now been all but confirmed by watching the motion of Ganymede's aurorae. Saltwater can carry an electric charge, meaning that watery currents deep inside Jupiter's moon affect its magnetic field and, in turn, affect the aurorae dancing in its skies.

Ganymede has so much water that it may contain more than all of Earth's oceans combined! Below about 95 miles of hard, icy crust, NASA mentions that Ganymede's oceans are expected to be 10 times deeper than the oceans here on Earth. There's so much water hiding inside the moon that there's a possibility it forms a continuous layer surrounding a rocky core deep inside the icy moon. If this is the case, Ganymede's crust might even be totally decoupled from its interior, meaning that the world's core and crust could rotate at different speeds.

Life on Ganymede?

With an ocean full of liquid water lurking underneath Ganymede's crust, there's a chance that Jupiter's hulking moon may even be home to some kind of extraterrestrial life. Water is essential to life as we know it, and with all the right ingredients present, the solar system's icy moons may be the best chance for us to discover alien life in our solar system. Protected from harsh cosmic radiation, living things could thrive in the darkness below the surface of an icy moon, perhaps in places resembling the deep sea ecosystems found around hydrothermal vents on Earth's ocean floor.

While many people champion Europa as the best place to look for life, there's a good chance that neighboring Ganymede might be an even more likely home for living things, per Forbes. It's long been the most overlooked target for astrobiologists but, all things considered, it has all the right conditions for life to arise. The difficult part with any subsurface ocean, though, is how scientists might find any traces of it. With a thick icy crust in the way, any signs visible on Ganymede's surface may be few and far between. Perhaps the only way to know for certain will be sometime in the future when we might be able to actually send something down below the surface. Optimistically though, perhaps the Juice spacecraft might uncover some clues when it arrives at Ganymede.

Long dead tectonics

Another way in which Ganymede is similar to Earth is its surface. The uneven terrain of Jupiter's oversized moon is patchy and covered with unusual grooved terrain. According to a study in the journal Icarus, it shows signs of strong tectonic activity in the past. Ganymede's surface is a jumbled patchwork of lighter streaks and darker, much more ancient terrain, and is seemingly covered in the same kind of slip-strike faultlines which cause earthquakes here on our own planet. Ganymede has so many of these faultlines that the scientists studying them were taken completely by surprise. It seems Jupiter's large moon may have seen some cataclysmic activity in the past, likely including cryovolcanoes — volcanoes that erupt ice instead of lava. However, unlike Earth, and even neighboring Europa, Ganymede's tectonic activity seems to have long since seized up.

Ganymede's surface now is frozen and silent, its motion having long since stilled. Hints at its past activity can still be seen though, by looking at craters. The older dark terrain is full of unusually shallow craters, which give clues about the moon's past. One explanation for the shallow craters is that Ganymede experienced episodes of heating in the past, partially melting these craters and flattening them out. Because Ganymede's surface is such a mixture of newer and older terrain, its surface is like a forensic crime scene. By looking at the moon's surface today, scientists can build up a picture of what happened in the past, and when.

ESA's Juice spacecraft

Juice was launched without a hitch and it now has a long way to travel out to Jupiter. The Planetary Society explains that it's an 8-year journey, with Juice due to reach Jupiter in 2031. When it arrives, the first thing it will do is enter Jupiter's orbit. There, ESA scientists will send it on several close flybys of Jupiter's icy moons, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Each moon has different things to tell us about the distant past and the potential for extraterrestrial life. But Ganymede is the main target. Its magnetic field, hidden ocean, icy shell, and past tectonic activity are all things that Juice's mechanical eyes will be paying close attention to.

With all going according to plan, Juice's endgame is to enter orbit around Ganymede itself, becoming the first spacecraft to ever orbit a moon other than Earth's own. Once there, it'll give an unprecedented close look at the surface of Ganymede and use radar to peer inside Ganymede's icy shell. With luck, it may find traces of biosignatures, giving hints of whether or not there may be signs of life there. Even if there are no signs of life there right now, the information it returns is likely to be useful in the future too. It'll give invaluable help to assess whether it might be possible, someday, for humans to set foot on Jupiter's largest moon.

[Featured image by ESA | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO]