How Climate Change Could Affect Life In The Deepest Parts Of The Ocean

Climate change, as a topic of public debate, never seems to go anywhere. We know that Earth naturally cycles through cool and warm periods, and that temperatures in 2100 are on track to hit the same highs as they did 5 million years ago, per Climate Science. We also know that starting in 1850, right around the time that the Industrial Revolution swung into full gear, global temperatures started skyrocketing at an unnaturally fast rate. A zoomed-in timeline of the past 45 years or so shows that the last nine years (2014 to 2022) have been the nine warmest years in recorded history, Climate.gov reports. Such temperature increases have pervasive consequences that touch every aspect of life. But even though folks tend to focus on colossal, catastrophic consequences like rising sea levels, climate change penetrates all the way down to the ocean floor below.

Earth's oceans comprise a dense, delicate ecosystem of interconnected causes and effects. More carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere means more CO2 in the ocean, as the National Ocean Service says, which acidifies the ocean and makes it harder for ocean life to survive — particularly shelled organisms. This and superheated oceans affect everything from the smallest plankton to the largest whale, as the European Commission shows. Overfishing and oceanic waste dumping compound problems. Coral reefs near the surface have been hit the hardest and are dying worldwide, per the UN Environment Programme. But soon, not even the darkest, coldest places of the seas will remain undamaged.

Sunlight, Twilight, Midnight

Understanding the effects of climate change on the ocean requires understanding exactly how deep the ocean is. The National Ocean Service says that the average depth of the ocean — taking its shallowest and deepest parts into account — is about 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers). In the bottom of the Mariana Trench rests the deepest spot of the ocean, Challenger Deep, at a staggering 35,876 feet (10,935 kilometers) deep. To put things in perspective, that's about 7,000 feet deeper than Mt. Everest is tall, per the National Ocean Service.

There's an entire, self-contained world within Earth's oceans, full of life that seems absolutely alien to landbound creatures like us. Oceans cover 70% of Earth's surface, but we've only explored about 20% of them, as the National Ocean Service cites. Even only 35% of the coastal regions around the U.S. have been mapped, and that's using modern sonar equipment, not first-hand exploration.

As Vox explains, scientists split the ocean into layers of depth depending on how deep light penetrates. The top, brightest layer is called the sunlight zone and spans from the surface to 200 meters deep. Under that is the murky, blueish, dimly lit twilight zone, which spans from 200 to 1000 meters deep. Under that is the utterly black, lightless midnight zone, which spans from 1000 to 4,000 meters. Below this are the abyssal and hadal zones reaching down to 11,000 meters deep. Each of these zones comprises its own ecosystem that interacts with the others.

The flow of matter and light

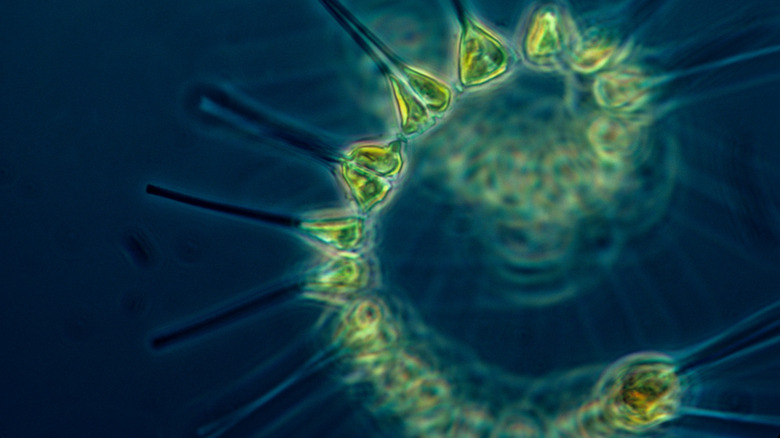

When folks go scuba diving in brightly lit waters, they're in the ocean's sunlight zone. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution explains that the sunlight zone only encompasses 2 to 3% of the world's oceans but contains many recognizable animals and features, like coral reefs and phytoplankton. Phytoplankton, aka microalgae, are underwater microorganisms that produce chlorophyll-like plants, require sunlight to live, and contain a host of nutrients, per the National Ocean Service. They're also the most critical part of the ocean's entire food web because they're the bottommost component — they get eaten by bigger lifeforms, which get eaten by bigger lifeforms, and so on. They also produce about half — yes, half — of all of Earth's oxygen. Suffice it to say, if climate change drives phytoplankton to extinction, we're in big trouble.

The bottommost layers of the ocean, by contrast, are roiling, ultra-pressurized regions of extreme environmental conditions. They contain immense trenches, thermal vents, shifting tectonic plates, and are home to lifeforms found nowhere else on Earth, per the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Creatures in the deepest parts of the ocean never touch sunlight, ever. They rely on vibrations and bioluminescence — chemically glowing body parts — to communicate. Lifeforms down there are unbelievably hardy and consume carbon-based matter descending from upper layers and settling on the ocean floor. Climate change can alter the flow of materials down to Earth's deepest oceanic recesses and wreck ecosystems we'll never even see.

Deep-sea carbon capture

In between the uppermost and bottommost oceanic layers rests the twilight zone, a zone as eerie and mysterious as the name implies. The twilight zone has gotten a lot of attention from researchers in recent years because it's at particular risk from climate change. The twilight zone — also known by its scientific name, the mesopelagic zone — sees lifeforms beginning to use bioluminescence to communicate and contains a dense variety of sharks, fish, and other animals in a nutrient-rich environment. A 2014 paper published in the journal Nature suggested that the twilight zone might hold up to 10 times as many fish as previously assumed.

The twilight zone, sandwiched between the effects of the zones above it and below, is subjected to changes in either region. Dead matter and waste products drift down to the region and provide sustenance for life, and Vox explains that the zone itself acts as a kind of carbon trap — carbon that goes there doesn't rise back up. In fact, the twilight zone might play the single biggest role on Earth related to transporting and containing carbon, as creatures migrating through the region carry 2 to 6 billion metric tons of carbon with them every year. For comparison, all the planet's cars produce about 3.6 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide every year. And as scientists on Vox and The Guardian describe, all life in the twilight zone is at risk of being completely obliterated by climate change.

[Featured image by Olga1969 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Twilight's end

Sites like the Woods Hole Oceanic Institution go into greater depth about climate change affects the twilight zone, and about the importance of the twilight zone to keeping life on the surface safe. Much of the power of the twilight zone to regular carbon intake comes from the migration of its lifeforms. Migration in this case means daily migration up toward the surface and then back down to the depths. The twilight zone is partially lit, remember, but covers a wide swath of warmer and lighter at the top to darker and colder at the bottom.

It's the lifeforms of the twilight zone themselves — bristlemouth and angler fish, pelican eels, numerous squid species, and more — that collect carbon in the form of matter floating down from the surface above. They swim up during the day, and recede down at night, eating along the way and physically ingesting carbon. Whatever isn't caught by them will continue to float down, possibly all the way to the ocean floor.

As CNN says, research indicates that the twilight zone wasn't always so alive. Warmer times in Earth's history have left it barren of life, down to the bacteria, because matter decays more quickly in higher temperatures. On The Guardian, postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Exeter Katherine Crichton said, "Unless we rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this could lead to the disappearance or extinction of much twilight zone life within 150 years, with effects spanning millennia thereafter."

A matter of survival

The threat climate changes poses to the ocean's deepest layers is horribly self-perpetuating, much like the loss of ice on Earth's surface. As Climate Policy Watcher explains, shrinking ice caps means less ice to reflect the sun's rays, which causes Earth's atmosphere to heat up even faster. The same thing is true of damage to the ocean, particularly to the twilight zone. Increased temperatures kill life in the twilight zone, which means less carbon captured, which kills more life, and so on.

Concerned scientists are doing their best to gather evidence on the effects of climate change on ocean life, as well as inform the public about their findings. On CNN, Luiz A. Rocha of the California Academy of Sciences points out that the twilight zone is doubly at risk because it's difficult to study, and we wouldn't realize the extent of the damage occurring down there until it's too late. He also points out that we're heading into uncharted territory and have no historical precedent for how to proceed. Moreover, he reiterates that protecting the oceans is a matter of addressing climate change on the whole, not only targeting the ocean. "A marine protected area ... makes very little sense because the impacts that are affecting it are global in nature," he said. "What we really need ... is to stop, or at least slow down, the high rate of change that we are subjecting our planet's climate to."