What Happened To The Bodies At The Alamo?

The famous Battle of the Alamo started near San Antonio, Texas, on February 23, 1836, and lasted until Mexican troops under the command of General Antonio López de Santa Anna breached the fort on March 6, 1836. It was preceded by the start of the Texas Revolution in October 1835, when Texans (including Anglo settlers known as Texians) fought back against Mexican control of the territory.

The Catholic friars who oversaw the Alamo's construction in the early 18th century never intended for it to be a military fortification. It sprawled across three acres, with adobe walls that proved difficult to defend. With so few tactical advantages, holding the Alamo was a daunting task for defenders like frontiersman and politician Davy Crockett. It didn't help that garrison commanders William Travis and Jim Bowie slacked on siege preparations, leaving defenders short of supplies and caught off guard. When the siege broke, women and children were spared, but all defenders either died in the battle or were executed afterward.

Around 200 Alamo defenders died, as well as anywhere from 600 to 1,600 Mexican soldiers, depending on which account you read. As the story of the Alamo grew to mythic proportions, many wondered: What happened to the bodies? Whether they simply wanted a complete record or needed a burial site to commemorate the dead, finding the remains of defenders, in particular, proved important. Yet, the answer to what happened to the bodies of the Alamo is far more complicated than you may think.

Many reported the defenders' remains were cremated

The widely accepted fate of most of the Alamo defenders' remains is a fiery one. As published in a July 1906 edition of the San Antonio Express (via Timothy M. Matovina's "The Alamo Remembered"), eyewitness Pablo Díaz, a teenage resident of 1836 San Antonio, recalled seeing a large column of smoke rising from the fort. Later, he encountered the gruesome sight of many Mexican corpses, then came upon the fort and the remains of the defenders: a smoking mass of ashes, grease, and bone fragments that gave off a sickening odor. Díaz claimed around 200 bodies were put on the massive pyre.

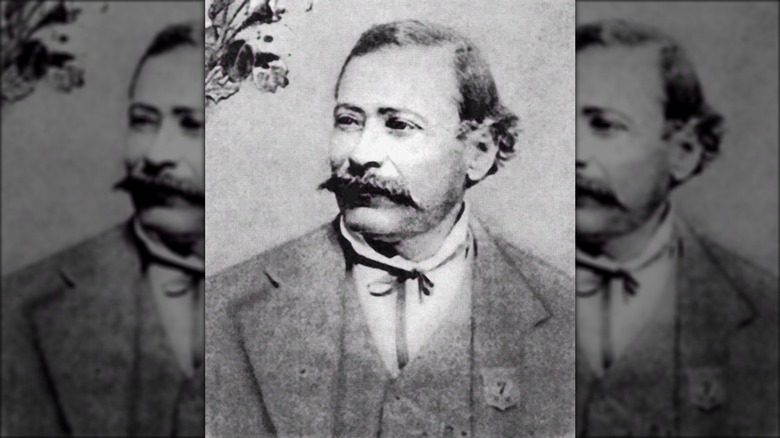

Another account comes from Francisco Antonio Ruiz, the alcalde (magistrate) of San Antonio, whose story was reprinted in a 1907 edition of the San Antonio Light. Due to his position, Ruiz was asked to help identify remains. He also directed locals to gather wood for the pyre, which he said was built in alternating layers of wood and bodies (182 remains, by his reckoning). It was lit the evening after he had first visited the Alamo to view the deceased. Later, after the fires had burned out, anything that was left was reportedly buried in a pit nearby.

Santa Anna ordered a more traditionally decent burial for fallen Mexican soldiers. However, the reality of war made that difficult. Ruiz claimed that there were so many Mexican dead (he estimated 1,600) that overwhelmed locals simply tossed some bodies into the river.

What actually happened to all the dead is hard to pin down

Cremation may not have been the fate of all Alamo dead. In the aftermath of the chaotic battle, remains could have easily been passed over by weary Mexican troops. Santa Anna himself later wrote that he ordered the burial of some 600 enemy dead in trenches, though eyewitness accounts, the number of Texans, and the lack of an excavated mass grave make that hard to believe.

There is, however, some indication that burials did occur at the Alamo. People later recovered recognizable human bones in the ruins of the church, hinting that a burial may have occurred. One set of remains uncovered beneath the Alamo mission in 2019 was even associated with pieces of wood and a series of nails indicating a coffin. However, burials happened in the mission before the Battle of the Alamo.

There may have been defender remains outside the walls, too, though how they got there is hardly in keeping with the narrative of noble defenders. According to some Mexican soldiers' accounts of the battle, large numbers of Texians attempted to make a run for it once it was clear that the Alamo was going to fall. Yet they quickly met their deaths when they came across Mexican soldiers. If those recollections are to be believed, it's possible that some defender remains were forgotten amid the brush or became part of the masses of corpses buried or thrown into the river by locals.

Mythmaking soon made honoring the remains all the more important

Not long after the Battle of the Alamo left the fort and its defending force in ruins, legend began to take shape. Davy Crockett was transformed into a heroic figure who went down guns a-blazing (though other stories said he surrendered). One tale has William B. Travis firing off one last round after being struck by enemy fire. Another gives Jim Bowie, who was sick in his bed at the time of the attack, an opportunity to at least verbally strike back at Mexican soldiers before his martyrdom. A heavily dramatized (and likely fictional) retelling has Bowie informing one Mexican soldier that "I shall never shut my mouth for your like." After the pyre was lit, one man reportedly said, "It takes him up — to God" (via Bill Groneman's "Eyewitness to the Alamo").

For many, determining whether or not these stories were true was beside the point. The growing myth of the Alamo held that the defenders were stalwart champions of liberty who stood up to the tyranny of Santa Anna and the Mexican government. As the years went on, having a site to memorialize the glorious dead was increasingly important to patriotic Texans who became Americans.

To that end, in 1918, two memorials were erected at the site of the Alamo funeral pyres. Well, more or less the spot. Today, no one's sure where the memorials ended up, but the likely sites for the pyres are beneath a couple parking garages.

Only one defender is confirmed to have been buried

José María Esparza, also known as Gregorio, was in a difficult situation in the lead-up to the Battle of the Alamo. A resident of San Antonio, he was a seemingly normal family man who assisted the Texians in the Siege of Béxar in December 1835. By the time Santa Anna's forces came to town in February 1836, Esparza and his family — wife Anna and four children — retreated to the Alamo. They believed that, with all their past assistance to the Anglo Texans, they might be marked as traitors worthy of harsh punishment. The family entered the Alamo through a small window in the fort, getting in shortly before the siege began.

All of the members of the immediate Esparza family stayed in the Alamo during the battle, with Gregorio joining the fight by stationing himself at a cannon. He died alongside many others during the battle on March 6, 1836. His wife and children, along with the other female and minor noncombatants sheltering in the Alamo, were spared.

Esparza's family wasn't universally friendly to the Texians, however. Gregorio's brother, Francisco, was serving as a Mexican soldier at the time of the battle. He did not take part in the assault on the Alamo but was close to the scene. Francisco gained permission to find his brother's body in the ruins of the fort. With two other brothers, Francisco buried Gregorio's remains in the Campo Santo, a nearby Catholic cemetery.

Many Mexican remains were left in the open

About 600 to 1,600 soldiers under the command of Santa Anna were killed at the Alamo. Others estimated the number to be even higher. Speaking in July 1906 to the San Antonio Express (via "The Alamo Remembered"), eyewitness Pablo Díaz claimed that the area contained almost 6,000 Mexican remains. He vividly recalled waterways clogged with corpses, as the number of the dead was so monumental that some were tossed into the river instead of receiving a burial.

This gruesome sight of bodies left to decompose in the open was repeated later after the Battle of San Jacinto, fought near the future site of Houston on April 21, 1836. There, General Sam Houston led a force of about 900 against an estimated 1,200 Mexican soldiers. Shouting, "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!" the Texan army defeated Santa Anna's forces and established the territory as an independent state.

They also left the grisly sight of unburied Mexican soldiers scattered across the landscape, as Houston refused to bury any enemy combatants. Landowner Peggy McCormick went to Houston himself to complain about the corpses decaying on her property but was met with only platitudes about the honor of owning the land where the decisive battle of Texas independence was won. Houston also apparently wanted Santa Anna to carry out the dirty work, but the Mexican general wasn't about to budge, either. McCormick and her sons were forced to bury the remains themselves.

The fate of the ashes is murky

Some accounts state that the ashes of defenders were simply buried near the pyres. Yet some weren't willing to let the story end there. In 1837, Texan Lieutenant Colonel Juan Seguín told the Telegraph and Texas Register that, when his troops arrived at the Alamo almost a year later, they found a large portion of the ashes still lying in the open. They placed the ashes into the coffins and buried those in an unspecified spot. Multiple accounts point to a peach orchard as the spot, but none seem able to give directions to the exact location.

Indeed, the burial place was so vaguely defined that it has caused consternation for generations. Seguín himself didn't help things when, as an elderly man, he said that the ashes his troops recovered had actually been placed in an urn (via The Southwestern Historical Quarterly). He claimed that he had also ordered a statue opened in what he called the Cathedral of San Antonio, implying that the ash-filled urn was secreted away somewhere in the grand church now known as the San Fernando Cathedral.

In 1936, Texans claimed to have uncovered the quasi-mythical ashes beneath the cathedral's altar. They reinterred the supposed remains in a marble sarcophagus that's still on display in the church today. Yet, with all the confused history and uncertain provenance of the sarcophagus' contents, there's little hope that we'll ever know if the ashes inside are the real deal.

[Featured image by Svs220 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Remains were uncovered decades later

Many accounts make it seem as if all the remains inside the fort were promptly cremated to ashes. Yet, Santa Anna and his soldiers weren't quite so efficient. An open-air pyre of the sort thrown together at the Alamo simply wouldn't produce the same fine ashes made by a modern crematorium. That's borne out by eyewitness testimony. In 1906, an elderly Pablo Ruíz, who saw the smoldering pyres as a teenager, told the San Antonio Express that he saw recognizable bone fragments in the pile (via "The Alamo Remembered").

It's also possible that some remains were simply missed. Exhausted soldiers could have easily passed over the bodies of defenders that had been left concealed by the rubble of the fort, which Mexican soldiers set on fire after the battle. Perhaps that confusion is why there were still skeletons to be found in the ruins of the church in 1846 if the account of Sergeant Edward Everett is to be believed. The existence of non-cremated human remains in the ruins is echoed by author William Corner, who wrote in 1890 that the skeletons uncovered at the Alamo were even found alongside fur caps and buckskins. But was this a genuine find of defender remains or an embellished tale riffing on Everett's earlier, less-colorful narrative? Teasing out the truth more than a century later may be impossible, but it's reasonable to conclude that not all of the defenders' bodies were disposed of on a funeral pyre.

One skull offers tantalizing evidence about Alamo burials

In 1979, archaeologists working at the Alamo uncovered a partial human skull during the excavation of an 1836 trench (via Index of Texas Archaeology). Researchers were able to glean enough information from the remains to wonder if they'd found a defender burial. First, the individual was male and was in their late teens to early 20s. Forensic analysis conducted in 2014 indicated that the young man was possibly Anglo, though the remains are missing key features like cheekbones and full eye sockets which makes definitive conclusions difficult.

In the decades since its excavation, the partial skull has proven to be pretty contentious. First, it may not be that of a defender, as Indigenous people and individuals who died in earlier conflicts of the Texas Revolution may also be buried nearby. All told, it's estimated that over 1,000 individuals are buried in and around the Alamo, including the remains of Spanish colonists, emigrants from the Canary Islands, and Indigenous people who built and lived around the mission. This all makes it exceedingly tough to link remains to the 1836 battle.

This also introduces serious legal and ethical quandaries. It's possible that the skull belonged to an Indigenous man and so needs to be returned to a tribe for reburial, as both the Inter-Tribal Council of American Indians and local Catholic authorities have requested. Currently, however, the skull is in the possession of the University of Texas, and as of this writing, no DNA testing has been conducted.

Local tribes say their dead are connected to the Alamo

Indigenous people were more than mere background presence at the Alamo. They were the ones who built the complex, originally known as the Mission San Antonio de Valero when it was founded by Spanish missionaries in 1718. Some of the native people from the diverse array of tribes who lived and worked around the mission were laid to rest there, too. Indeed, hundreds of people were interred at the Alamo long before the 1836 battle.

Moreover, at the time of the Alamo battle, some of the Mexican forces besieging the mission were Indigenous men who had been conscripted from villages as the army marched north through the harsh winter. Some of the dead on Santa Anna's side were likely not the descendants of Spanish settlers, but Native Americans who had already been hit hard by the effects of European colonization.

All of this means that, when it comes to bodies uncovered at the Alamo, some surely don't belong to defender Texians, but to Indigenous people from a wide territory. This possibility is important to modern tribes like the Tāp Pīlam, who want to ensure that their ancestors are left undisturbed while also acknowledging the diverse history of the Alamo. Tribal representatives have sometimes taken legal action to ensure that they are consulted when remains are discovered. What's more, the presence of these burials makes it more complicated to determine just what happened to the casualties of the 1836 battle.

Defender remains might have been found at the Alamo in the 21st century

It might be easy to think that the forces of time and modernization have washed away any chance of finding something new at the Alamo. But while the crowds of tourists might complicate things, archaeologists can tell you that the site still has plenty of new information to offer. As recently as 2019, even more human remains were discovered as archaeologists surveyed an area ahead of renovation work. (Other excavations in 1989 and 1995 also unearthed remains.)

The 2019 discovery involved the excavation of three separate burials of a teenager or young adult, an infant, and an adult. Significantly, they were uncovered in what's now known as the Monk Burial Room and the nave of the mission's church. Though it's not clear exactly who was interred here or when they were buried, some have argued that the younger adult was an 1836 defender. Their reasoning? That individual — represented by just two femurs at the time of the excavation — was found with what appears to be the remnants of a coffin. That points towards an Anglo, as people from other groups were more often buried in cloth shrouds. However, there is no indication that any dating or DNA testing has been done to more definitively link the remains to the Battle of the Alamo.