Political Scandals That Rocked Early America

In the age of the internet, 24-hour rolling news, political partisanism, and populist politicians who blur the line between politics and celebrity, it is perhaps no surprise that we are inundated with political scandals. Political corruption, illicit affairs, conflicts of interest, and even attempts to subvert democracy itself have all hit the headlines in recent years. And today, with our cell phones, laptops, and TVs always near at hand, it is almost impossible to look away.

But is our century really more scandalous than any other? Were people better behaved in the past, when manners mattered and every statesperson, it seemed, was a grand orator with the interests of the people at heart? Or were they just as calculating, selfish, suspect, and flawed as those with their hands on the levers of power today?

They say history repeats itself, so it should come as no surprise that the politicians of early America perhaps pioneered scandals that we would (or wouldn't) scoff at today.

The XYZ Affair

Listed as one of the "Events that Changed America in the Eighteenth Century," by historians John E. Finding and Frank W. Thackray in their book of the same name, the intriguingly named "XYZ Affair" brought the United States and France to the brink of a full-blown conflict. Indeed, the events of the XYZ Affair, which played out between 1798 and 1800, saw the two nations entangled in what historians now describe as a "Quasi War."

The affair began with France instigating a new policy to capture American cargo ships to shore up their shrinking military budget at a time of multiple conflicts in Europe. Relations between France and the U.S. had also been strained as a result of the latter's recent treaty with Britain, much to the annoyance of France.

Realizing the need to settle the waters between the two countries, U.S. President John Adams (pictured) sent three of his diplomatic envoys to France, who presumed they would be granted an audience with the French Foreign Minister, the Marquis de Talleyrand. But despite the severity of the situation, Talleyrand did not appear, sending four envoys of his own — codenamed "W," "X," "Y," and "Z" when the story broke in the U.S. — to meet the delegation in his stead. The snub was compounded when the French representatives hit the American envoys with a list of demands, including a hefty bribe for the foreign minister. Shocked by the demands, the American delegation sent word to Adams that their mission had been unsuccessful. The American public was scandalized, and Adams prepared for war. Although numerous skirmishes broke out between American and French ships after, a resolution was finally brokered in 1800.

Alexander Hamilton's sex scandal

Alexander Hamilton has had something of a renaissance in terms of his contemporary fame. But the Founding Father's life was not without controversy. Specifically, Hamilton set a precedent for presidential sex scandals with the revelation of an affair he was having with a married woman named Maria Reynolds.

Maria had first made contact with Hamilton in 1791, when she approached him for help regarding her husband, James Reynolds, whom she claimed was abusive towards her and her children. Hamilton helped her with money, but they also began an affair. Soon, James found out about the affair and began to blackmail Hamilton for large amounts of money in order to keep the affair a secret. Knowing that such a revelation would be damaging to his political career, Hamilton paid his blackmailer what he demanded, though the affair ended and the blackmailing stopped. Eventually, James Reynolds was imprisoned for a separate scheme involving defrauding the government.

However, rumors soon spread that rather than James Reynolds blackmailing Hamilton, the two had been involved in another illegal speculation together as accomplices. When Hamilton was later accused publicly, he was forced to be open about the true nature of their relationship and published the "Reynolds Pamphlet" in 1797, which also contained detailed accounts of his affair with Maria. It cost him his reputation and his standing as a potential presidential nominee.

The controversial life of Aaron Burr

Alexander Hamilton's life came to a tragic end in 1804, when he was shot and killed in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr. The duel was partially responsible for Burr's dramatic fall from grace as a political force but left him licking his wounds and plotting a comeback. However, the events that followed, known today as "The Burr Conspiracy," put an end to any chance of that.

When his vice presidency ended in 1805, Burr headed west, touring the western states and seeking out opportunities to build funds and political favor. However, rumors began to spread that the downtrodden politician was potentially planning something more than a possible future election campaign. Traveling hither and thither, observers noted that Burr was seemingly recruiting men to join him in an ambitious plan to subvert the federal union and set up his own empire. How many supporters Burr gathered is still debated, but as his actions became more widely known rumors soon spread that he was gathering supplies for such a plan, and that he was attempting to make a deal with Britain to seize western territories from the U.S.

After reports of Burr's suspicious movements got back to President Thomas Jefferson, Burr's plan unraveled, and he was put on trial for treason. Though he was acquitted due to a lack of tangible evidence against him — that the details of his plans are still sketchy today shows how word-of-mouth his supposed conspiracy was — he became a figure of hate in America and beyond, and his political career never recovered.

The Blount Conspiracy

Founding Father William Blount was a senator who, in 1797, had the ignoble distinction of essentially being caught red-handed during a Senate meeting. Coming in from a short walk, all eyes were on Bount as a clerk was reading from an incriminating document. The document was a letter Blount had written to a man named James Carey, hatching a plan to allow Florida, which was then controlled by Spain, and Louisiana to come under the control of the British by having Native American militia groups attack both. Unlike the Burr Conspiracy, the precise details regarding the Blount Conspiracy are evident in black and white, in multiple documents, which were later published in the American Historical Review, that prove the senator in question was in direct contact with Britain via letter, and that he personally had discussed plans for the invasion.

Blount was impeached by the Senate but fled back to his home state of Tennessee, where he rebuilt his career on a state level. He never returned to Washington.

The Murder of Philip Barton Key II

As the death of Alexander Hamilton at the hands of Aaron Burr demonstrates, early American politics were notable for displays of violence. But while the death of Hamilton came about in an organized duel, half a century later another young life was lost in a sudden and cold-blooded attack at the hands of an American politician.

Daniel Edgar Sickles was a noted 19th-century congressman, a veteran of the Civil War, and an instrumental driving force in the creation of Central Park in New York. But he was also a killer. In 1859, he received an anonymous letter informing him that his wife, Teresa Sickles, was having an affair with Philip Barton Key II, the district attorney of Columbia who was the son of Francis Scott Key. Though Daniel strove unsuccessfully to determine who wrote the letter and to verify whether the story it told was true, he was eventually propelled into a blind rage. He took to the streets of downtown Washington, D.C. to find Philip, and, on finding him, shot the lawyer to death on the corner of Lafayette Square.

The killing was major news, and Daniel Sickles was put on trial for Philip Key's murder. Daniel, however, pled temporary insanity — the first defendant in American history to do so — and was acquitted by the jury. Surprisingly, while his shooting of Philip undoubtedly besmirched his reputation, his political career was somehow able to continue.

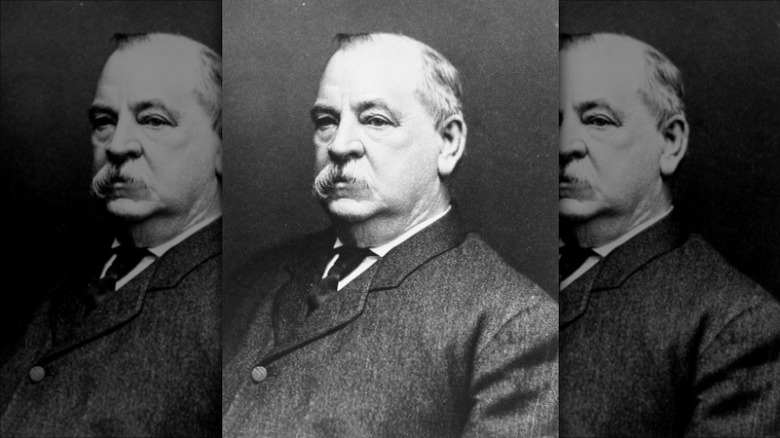

The brutal Grover Cleveland election campaign

If recent U.S. presidential campaigns have at all struck you as being unusually bad-tempered and dirty in how they are fought, rest assured that mud-slinging in the presidential race is something of an American tradition.

The campaigns leading up to the U.S. presidential election of 1884 were particularly rough. In particular, a Republican attack attempted to destroy the chances of Democratic presidential nominee Grover Cleveland using accusations of an extramarital affair. A decade earlier, Cleveland, who until the campaign was serving as governor of New York, had apparently fathered a child with a woman named Maria Halpin as a result of an extramarital affair on his part. The story hit the headlines, and while Republicans concocted vicious chants in reference to Cleveland's illicit affair, Cleveland went on the defensive. Rather than deny a story that was already known to many of his allies, he confessed to the public and suggested that his Republican opponent, James Blaine, was a habitual liar.

The election was a close call, but Cleveland managed to hang on and win the presidency. He would go on to serve again in 1893, the only American president so far to win two non-consecutive presidential elections.

The Rachel Jackson bigamy scandal

Though President Andrew Jackson's legacy is sullied today due to his support for slavery and the policies he enacted during his years in office that decimated Native American populations, he was, in his day, a hugely popular figure. But he too was the target of an orchestrated campaign by his Republican opponents to destroy his reputation in the run-up to the 1828 presidential election.

The drama that threatened to blow up in his face the year before the election involved his wife, Rachel Jackson, who, it was claimed, was a bigamist. Andrew's opponents claimed Rachel had been convinced by Andrew to leave her husband and take up with him. While their elopement was painted by his enemies as adultery, the fact was that Rachel had been trapped in an unhappy and abusive marriage, and that, when she left her husband, it had been publicized that he had filed for divorce. However, the divorce — an unusual occurrence in the early 1800s — never went through the courts.

The scandal led to Rachel being widely humiliated in newspapers across America, and she struggled with the strain it put on her. She was reportedly relieved when Andrew was victorious, and the campaign against her finally ceased.

The Brooks-Sumner Affair

On May 22, 1856, Congress was rocked by an instance of extreme physical violence inside the chamber the likes of which had never before been seen. It was an incident that shocked America.

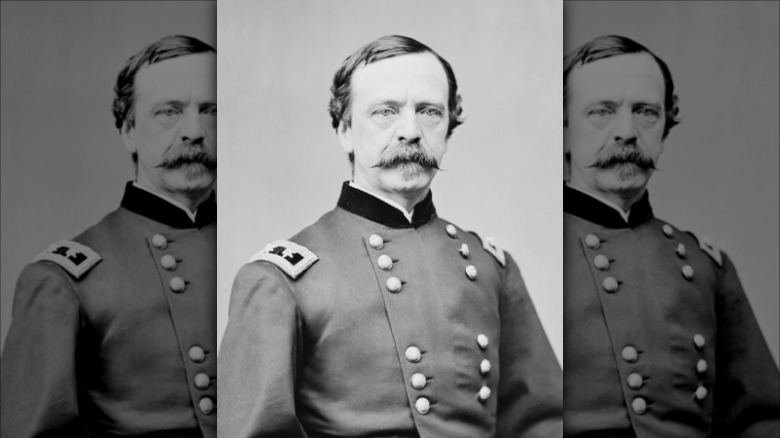

Known euphemistically as "The Brooks-Sumner Affair" but referred to in documents published by the Senate itself as "The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner," the incident occurred against the backdrop of rising tensions between pro-slavery and abolitionist groups in Congress. Three days earlier, Sen. Charles Sumner (pictured) had given a fiery speech eviscerating a number of public figures for their involvement in slavery. One of the target's allies, Sen. Preston Brooks, was enraged by his friend's treatment. Just after the day had adjourned on May 22, he spotted Sumner in the chamber, struck him viciously on the head with his cane, and continued to beat him for a full minute, leaving Sumner a bloodied mess. He would take years to recover.

The incident brought to the fore the reality that disagreements over the abject practice of slavery could not at the time be settled in the debating chamber. For historians, the Brooks-Sumner Affair may be looked back on as one step on the way to Civil War.

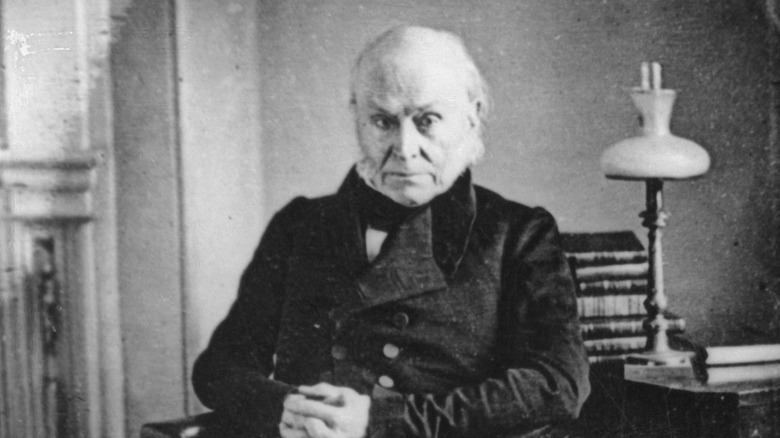

John Quincy Adams' 'corrupt bargain'

The Constitution is a work of political genius. Even so, the rules it lays out for the settling of elections and the transfer of power from administration to administration can still be cause for controversy, as was shown in the presidential election of 1824. That year, the election was fought between some of the biggest names in American politics: John Quincy Adams (pictured), the son of President John Adams, who had served for many years as the secretary of state; Andrew Jackson, who was a popular senator for Tennessee and considered a war hero; Henry Clay, speaker of the House of Representatives who was known as an effective political operative with a wide base of support; and William H. Crawford, a respected senator and treasurer.

With multiple candidates all wielding a large amount of popular support, when the results of the election arrived no one candidate was able to attract enough votes to secure a majority in the Electoral College. The constitution dictated that the result would then be settled in the House of Representatives. In the end, John Quincy Adams convinced Clay to support him and take a position in his administration and won the support of the House. Jackson, believing that John Quincy had bought votes among the representatives to secure his presidency, resigned from the Senate and wrote the election off as a "corrupt bargain," tainting John Quincy's victory ever since. However, in recent years academics Jeffery A. Jenkins and Brian R. Sala have returned to the 1824 election and employed spatial theory to show how the votes John Quincy Adams secured that day were likely honest (via the American Journal of Political Science).

The Crédit Mobilier Scandal

The railroad building projects of the mid- to late-19th century were some of the largest, most complicated, and ultimately most transformative transport infrastructure in American history. And many of the railroad-building projects undertaken at the time were bestowed by Congress upon a single entity: the newly chartered Union Pacific Railroad Company. Union Pacific was established as a project management and funding body that, for the purposes of construction, then created a separate building firm, Crédit Mobilier of America, to which Union Pacific awarded government contracts.

But with enormous budgets in play, such a set-up seems ripe for corruption, and indeed it was. The Crédit Mobilier Scandal saw Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Durant, who also operated as part of and had investments in Crédit Mobilier, award contracts to the company well above cost, allowing himself and other executives to pocket a fortune in the process.

But the scandal didn't stop there. Durant's successor at Crédit Mobilier, Congressman Oakes Ames, was alleged to have used the company's stocks to bribe his congressional colleagues to vote in favor of policies that aided the company and increased profits. When details of the schemes emerged, the backlash was enormous, leading to several censures, while others were absolved.

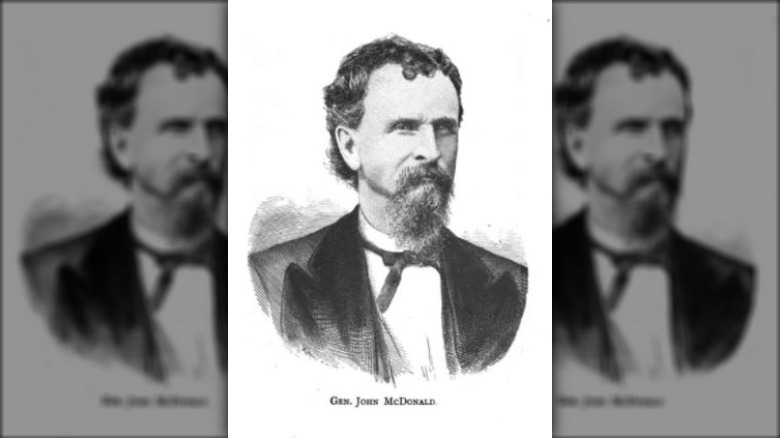

The Whiskey Ring Scandal

While many 19th-century American scandals didn't truly see justice served, the Whiskey Ring Scandal of 1871-1875 saw significant blame and prosecution of one of its political instigators.

The so-called Whiskey Ring had at its center Gen. John McDonald, a close friend of President Ulysses S. Grant who served as revenue collector in the state of Missouri. The state was home to several large whiskey distilleries, many of which as it turned out had made an agreement with McDonald to avoid paying excise taxes on the whiskey they produced in exchange for bribes for McDonald and several other government officials. Details of the conspiracy finally emerged in 1875 and caused a huge public outcry.

McDonald was prosecuted and spent 18 months in prison, one of 110 convicts sentenced for their involvement in the Whiskey Ring. He later published a tell-all book, "Secrets of the Whiskey Ring," in which he attempted to implicate a number of prominent politicians, including Grant himself. Though Grant was never officially charged with any involvement in the scheme, the proximity of several of his most senior officials to the Whiskey Ring irreversibly damaged his reputation.