Going To The Beach: The Strange History Behind The Pastime

Assuming you don't already live by the beach, a vacation there can sound positively idyllic. Just imagine relaxing on the sand, book in hand, or maybe simply dozing to the sound of waves breaking against the shore. More adventurous or curious people have plenty to enjoy by the ocean, too, from big wave surfing to examining the temporarily captive inhabitants of a tide pool. As if that weren't enough, many resort towns also boast beachside promenades with shopping, food, and seemingly endless people-watching.

As much as those cultural touchstones of the beach vacation may be cherished today, they're hardly set in stone. Humans have had a complicated relationship with the beach over the centuries, variously treating it as an entry point to the menacing ocean, a healthful spa, or a place to show off their wealth and social standing. A simple beach vacation has come up against changing social norms surrounding our health and the often touchy topic of how to manage a human body — especially when a person is trying to get out of the ocean in a sopping-wet bathing dress.

And, as humans so often do, many beachgoers couldn't help but make things weird. Over the history of the beach, one might encounter clunky bathing machines, creeps with telescopes, and especially unfortunate vacationers who were all but forced to drink seawater. Even today, the sight of people tanning or frolicking on the sand can call forth some odd facts. Here's the strange history behind going to the beach.

For centuries, the beach was terrifying

For many, the ocean is a scary place. Given that we're land-based mammals who are dependent on breathing air and not water, this fear makes sense. The ocean is also deep, dark, and cold. It's the domain of strange beasts, from real sharks and whales to fantastic creatures like the kraken, mermaids, and whatever may have made the bloop. Moreover, the sea presents an all-too-easy way to die. How many sailors set off from a beach into the vastness of the ocean, never to return?

As far back as the ancient world, people also feared the sea for what it might produce, from deadly monsters to human invaders. In the medieval period, that also included disease, as the virulent illness known as the Black Plague entered many nations through ports.

As the entry point to this chilling domain, the beach was poised between two worlds. Why would anyone want to linger there? It may have carried too many memories of lost loved ones ... or odd things churned up from the ocean's depths. Even by the beginning of the 18th century, which saw people slowly begin to accept the beach as a healthful (if not totally relaxing) place, the seaside was still plenty menacing. It was often depicted as the site of tragic shipwrecks and attacks by vicious foreigners, presenting a marketing problem for the seaside that would take many years to overcome.

Early beach trips may have been part of a doctor's prescription

Around the middle of the 18th century, Europeans started going to the sea under doctor's orders. However, lower-class folks, widely believed to be hale and hearty thanks to all that manual labor, were not generally given that advice. Rather, the leisurely, highly-domesticated lives of the rich sometimes caused worry. Would such ease cause more illness and slow human progress? Some physicians saw fit to send patients to the seaside, under the assumption that time spent next to the wildness of the sea would invigorate a languorous individual.

For those in Britain, their doctors may have specifically prescribed a dip in cold water for a similar reason. Water temperature was important, as many Enlightenment physicians believed it had a direct effect on vital processes like circulation and the composition of the body's humors. The shock of a freezing wave was said to get the blood moving and energize those affected by melancholia and other mood disorders.

That was all the more important for people living in cold climates, went the popular theory. They had to toughen up their bodies to thrive in the region's frigid air. What's more, a dip in icy seawater supposedly helped tamp down those pesky immoral urges that seem to have plagued humanity ever since shame became a concept. Someone might enter the water as a hopeless vagabond, but with a few good dunks, they just might leave a changed person.

Beach vacations could get torturous

As much as an 18th-century British person might hope that a beach trip would wash away their cares and straighten out their nerves, the hard truth was that it wasn't going to be easy. Health-minded visitors couldn't just expect to wade into the shallows and splash around a bit. Instead, they were more likely to be brought to the edge of drowning in the interest of improving their health. Attendants commonly known as dippers dunked beachgoers into icy seawater.

Not only were people plunged into churning, temperature-dropping water, but they were forced to hold their breath while doing it. And, no, this wasn't meant to be an exercise in self-control. Instead, those attendants could be employed to hold people down in the waves, just as the doctor ordered. The idea behind the torture was that people needed a good shock to their system, which was believed to help people calm down in the long term, at least after the initial trauma of being half-drowned subsided.

They would then be hauled out of the water and subjected to a rough backrub, mercifully capped off with a nice cup of tea. One hopes that also included a quick change into dry, warm clothing.

Some tourists were encouraged to drink seawater

As if being repeatedly dunked and tossed about in the waves wasn't bad enough, beach visitors of Enlightenment-era Europe were also sometimes advised to drink seawater. Doctors of the time thought they were harkening back to better-informed ancient eras, when physicians like the ancient Greek Hippocrates advised regular doses of ocean water. Eighteenth-century doctor Richard Russell went all-in on the trend, raving about the effects of seawater consumption in 1769's "A Dissertation on the Use of Seawater." He claimed that drinking the stuff could do all manner of wonders, including treating tumors, curing nasty skin lesions, and bringing on regular menstruation for those sickly ladies who were suffering a missing or inconsistent cycle (presumably a big concern for rich families who wanted to secure an heir or two).

The tourists who drank pints of seawater were lucky to survive (or perhaps they were sensible enough to pour the nasty pint out when no one was looking). That's because drinking the stuff is a terrible idea. The water from the ocean is so salty that your kidneys go into overdrive to flush the excess sodium out of your system. This means you urinate more fluid than what you would have consumed in that glass, putting you in a potentially deadly state of dehydration.

Early beachgoers assumed the ocean air was superior

So long as you don't have to smell a fish-killing red tide or a giant blob of rotten sargassum seaweed, fresh sea air is a nice prospect. But, as some early proponents of beach vacations claimed, the air at the seaside wasn't just vaguely better; it contained more oxygen overall. This is linked to yet another medical trend, as, by the late 18th century, scientists and doctors became more interested in the merits of fresh air than a bracing dip in the water.

Some of them claimed that beach air was more oxygenated than air inland. This is especially ironic given how earlier physicians warned of putrid air by the sea, made dangerous by the miasmas emanating from rotting organic matter thrown onto the shore.

Simplistic as this may sound, deep-breathing beachgoers may have been on to something. The Industrial Revolution saw factories spring up seemingly everywhere, while cities became crowded with people seeking work and other opportunities. All that human activity required heat and light, which for most of the 19th century required lots and lots of coal. The sooty clouds that soon hung over the cities and factories weren't exactly doing anyone's lungs a favor, and so the comparatively fresh air of the seaside must have felt like a relief. No, there wasn't strictly more oxygen at the beach, but it could have been a heck of a lot easier to breathe than what was at home.

Villages transformed into competing beach resorts

The growing crowds of beach-focused tourists weren't about to spend their expensive long-term vacations in ill-equipped backwaters. Neither were the residents of shoreside towns willing to let a good economic opportunity pass them by. Like so many people before and since, many beach locals turned to tourism in a way that completely transformed their hometowns.

The first known beach resort in Britain was the hamlet of Scarborough, which got in early on the health trend by selling local mineral water in the early 18th century. Many more popped up in the following decades, first focusing on the supposed health benefits of lingering by the sea and so catered to crowds of sickly tourists. But, as more and more people flocked to these resort towns, a new interest in having fun arose. These spots soon presented handy opportunities for the well-off to see and be seen while lounging and strolling on the beach.

For those who wanted to show off, beach towns had to up their game and emphasize the luxuriousness of their offerings compared to other resorts. After all, figures like the notoriously dissolute Prince of Wales (the namesake of the Regency Era and the future King George IV) weren't about to be seen in just any shabby old spot. As a result, the gout-stricken prince helped Brighton's reputation with his lavishly decorated residence the Royal Pavilion (pictured).

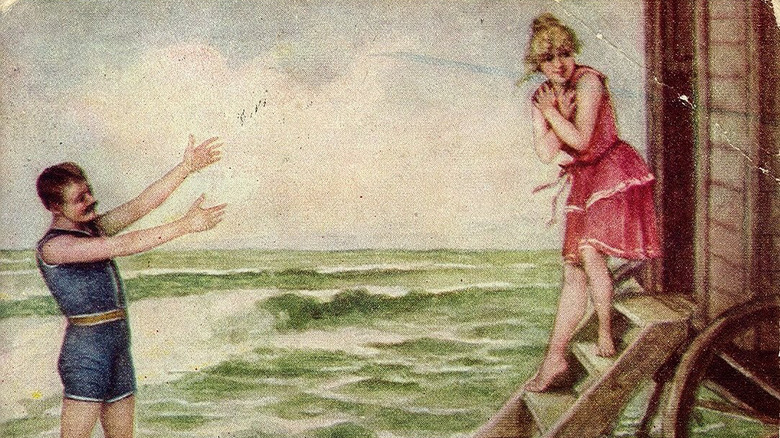

The beach made moralists anxious

As going to the beach became increasingly popular and larger crowds of people began to congregate at seasides everywhere, a new problem arose. Everywhere one looked, there were bodies on display. In the 18th century, writers sometimes went overboard with descriptions of swooning young women gasping as they were plunged into the sea. What's more, their and others' bodies were covered, but in fabric that tended to get awfully clingy when wet. Some men even went so far as to immerse themselves without a single stitch of clothing on, to the shock of 19th-century pearl-clutchers.

At least this was mitigated by gender-separated beaches where men and women were funneled far away from each other. But this was not a universal rule, as the specter of "promiscuous bathing" makes clear. In continental Europe and some of the more tawdry beach resorts of Britain, men and women could be seen splashing about the sea right next to one another. What's more, newspaper accounts of the late 19th century note that visitors to Margate, one of the more notoriously loose English resorts, brought along telescopes so they could get a better view of all that inter-gender frolicking (via author Mimi Matthews).

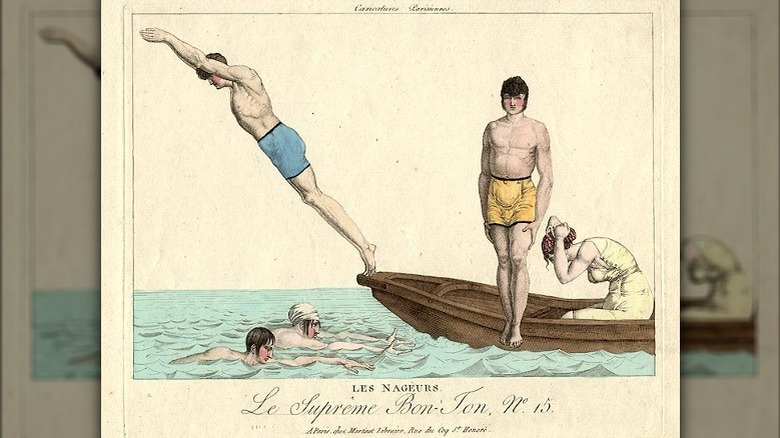

Victorian swimsuits could get extensive

Though modern beaches are packed full of people showing as much skin as possible, the first vacationers to beaches were downright terrified of admitting that they had a body. As in many other situations, a trip to the beach still required that most people cover up in long clothes and even hide away their hair (though that was more likely to be an attempt at keeping things neat rather than a nod to modesty). Long, shapeless bathing gowns might even have small weights sewn into the bottom hem to ensure that no scandalous bare-leg action might occur.

Men's bathing costumes, meanwhile, could be seriously varied. Some insisted on taking a dip while totally nude, claiming to enjoy the freedom and health benefits of full contact with seawater. Of course, society deemed these benefits forbidden for most women. Other men at least bothered to wear something, especially since some of the more conservative beach resorts required them to cover their bodies — chests included — well into the 20th century.

Then, fashion started to take over. While the Victorians were still pretty focused on modesty (especially where women's swimwear was concerned), the overall shape became more form-fitting, made from lighter fabrics, and often full of eye-catching trim and other design elements. As the 19th and 20th centuries rolled on, it became clear that close-fitting, decorated beachwear was sometimes more about showing off than covering up.

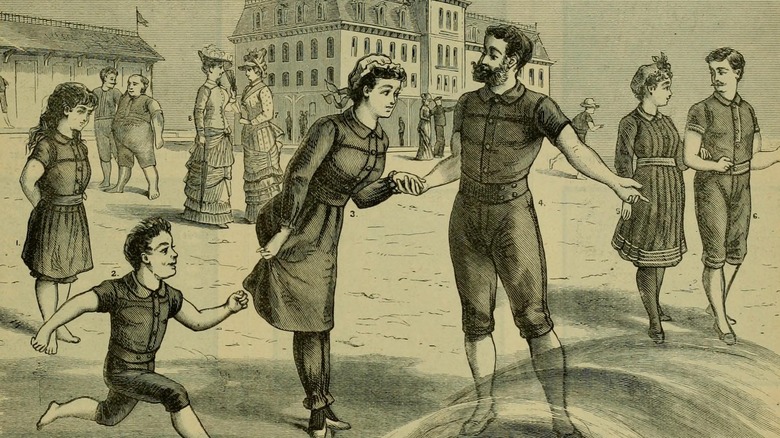

Bathing machines protected modesty

Vacationers of the 18th and 19th centuries often saw clunky wheeled contraptions on the shore or being rolled down into the waves. These were the infamous bathing machines.

The earliest records of them date back to the 1730s when visitors to Britain's Scarborough resort used them to get into the water while maintaining their propriety. The basic design was of a small shack on wheels, enough for a single bather to enter and change their clothes. A person, sometimes with the assistance of a horse or even a track, then wheeled the machine into the shallows and helped the occupant into the water. Some bathing machines were equipped with a cloth cover that extended from the machine to the water. For extra-shy beachgoers who wanted to avoid prying eyes, this was key, especially considering the presence of looky-loos who had their telescopes at the ready to catch every clingy detail. Of course, royalty and others with perhaps too much money to spare spent oodles on bathing machines decked out with mirrors, silks, and even (in the case of Queen Victoria) a working toilet.

Bathing machines continued to be popular into the 20th century, though as people grew less shy the contraptions largely became obsolete. Some were repurposed into stationary shacks meant for changing and storage, but now people expected to stride forth onto the beach on their own two feet.

[Featured image by John Leech/Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

A dipper plunged people into the water

The wan, low-energy folk who made a pilgrimage to health-focused beach resorts couldn't be trusted to safely enter and exit the churning waves. As both doctors' orders and the economies of beach towns prescribed, a burly local had to be present to make sure that visitors didn't drown while getting their health on. Dippers also had to maneuver the bathing machines into and out of the waters, using their knowledge of the beach and the waves to pick the right depth for their customer.

Some dippers even became locally famous for their services. Tourists who made their way to the Brighton beach resort in the late 18th and early 19th centuries might have encountered just such a person in the figure of Martha Gunn (pictured). Well, that is, if she wasn't busy hauling members of the royal family into and out of the water. Gunn, known for her straightforward, jocular personality, was such an esteemed fixture of Brighton that she appears in prints and poems from the time. All that heaving of George IV and his friends into the waves must have done her good, for Gunn worked as a dipper for more than six decades, dying in 1815 at the considerable (for the era, anyway) age of 88.

[Featured image by William Nutter/Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

Getting rays became all the rage in the 1920s

To modern folks, tanning has a seriously mixed reputation. Just take a stroll through the sunscreens for sale at your local store, and you'll see a bevy of products claiming to put a hardy barrier between your skin and the sun. For people who are especially prone to sunburns and skin cancers, this is a big deal (and as Columbia University notes, people of color can definitely suffer from sun damage and skin cancer, making sunscreen important for everyone). But go back a century or so, and getting a tan was so popular that beaches could be packed with sun-hungry people exposing their skin to UV radiation.

It all came down to health yet again. Where people of centuries past prized pale skin, the first decades of the 20th century saw a renewed interest in connecting with nature, skin and all. A glowing tanned skin, achieved by frolicking and laying about in the sun, was the outward indicator of a vigorous, healthful lifestyle. Unfortunately, this notion of an ideal sun-kissed body — which could only be fully achieved if one started with white skin — was such a widespread view that it became part of the warped views of bad actors like Adolf Hitler and Nazi collaborator Coco Chanel. The latter reportedly started a tanning trend when she played off a sunburn she'd gotten on a 1923 cruise.

Modern beaches are sometimes rebuilt

Beaches can be pretty ephemeral, as the ocean constantly reshapes the line between land and sea. Yet the sad truth today is that many beaches are also being loved to death. Large swathes of them are being sucked back out to sea, thanks in part to the effects of climate change and increasingly tumultuous waves, but also because humans just can't quit stomping all over them. Our interest in mining sand and blocking rivers also means that sand doesn't always get the opportunity to make it from inland to shore.

This leaves beach resorts in a pickle. Without a beach, there is little to bring tourists to brighten the local economy. Some have turned to importing sand, with places like Dubai paying for Australian sand to plump up its beaches (the more fine-grained desert sand doesn't stick around long enough to make its use worthwhile). The issue has gotten so bad that in places where governments have stepped in to limit sand mining black market economies have popped up in defiance of environmental concerns.

[Featured image by Diego Delso via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]