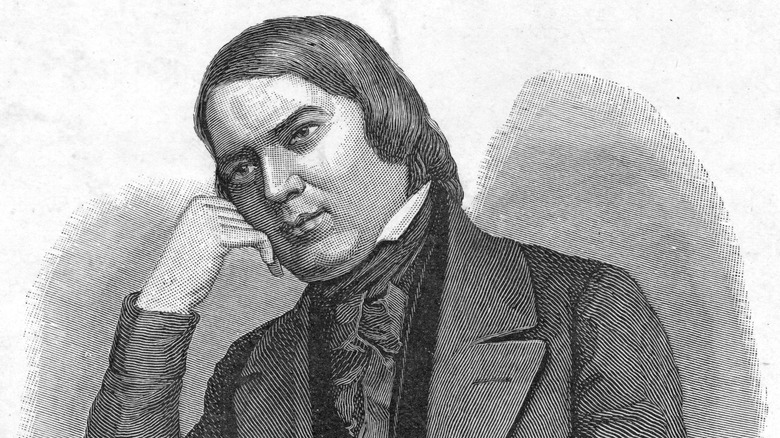

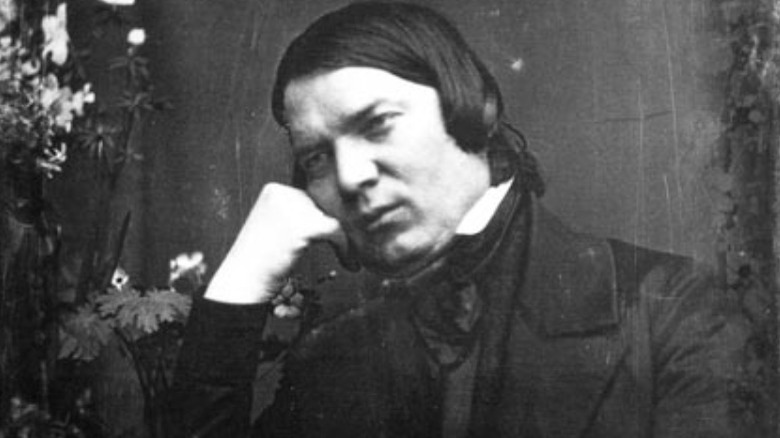

From Genius To Tragedy: The Life And Death Of Composer Robert Schumann

Although German composer Robert Schumann is now considered to be one of the greatest Romantic composers, his radical musicality wasn't as appreciated in his time as it is now. Composing several symphonies, chamber works, piano concertos, and vocal pieces during his 46-year-long life, Schumann is a quintessential tragic artist that burned fast and bright without being appreciated in his own time.

But even all the appreciation in the world couldn't have cured Schumann's mental state. He spent his entire life experiencing varying levels of depression, anxiety, and other mental health symptoms that many have tried to diagnose. In the end, composing music was likely as much of a way to survive his experiences as it was a way to earn money. And while it's often been said that artists must suffer for their art, Schumann created great music despite everything he experienced, not because of it. From genius to tragedy: This is the life and death of composer Robert Schumann

The following article includes numerous descriptions of suicide and depression. If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The early life of Robert Schumann

Robert Alexander Schumann was, born in Zwickau, Kingdom of Saxony, now part of Germany, on June 8, 1810, to Friedrich August Gottlob Schumann and Johanne Christiane Schnabel. His father Friedrich was a writer and founder of the Schumann Brothers Publishing Company, and he made sure the young Robert was exposed to various creative activities as he was growing up. According to the "Letters of Robert Schumann," edited by Karl Storck, Robert was taken to hear the compositions of Ignaz Moscheles when he was 9 years old. And just five years later, Friedrich recruited Robert to help write biographies of musicians for a collection.

When Robert was 7 years old, he started studying piano with Baccalaureus Kuntzsch, and it was during this early introduction to music that he started playing around with compositions for the first time.

But despite doing their best to provide for their children, Friedrich and Johanne struggled long before Robert came into the picture. One year before Robert was born, one of his siblings died as an infant, according to Mark Runco and Steven Pritzker's "Encyclopedia of Creativity." This put both his parents in an incredibly depressed state, underlined by the fact that Friedrich's father died around the same time as Robert's sibling.

Schumann's surrogate mother

When Robert Schumann was three years old, there was a severe typhus epidemic in Saxony. According to "Encyclopedia of Creativity," 9% of the population died as a result, and although Robert avoided infection, his mother Johanne Schumann fell ill and had to be quarantined. During this time, Robert went to live with another family and was given a temporary surrogate mother named Frau Eleonore Carolina Elisabeth Ruppius.

Initially, Robert was only supposed to stay with Frau Ruppius for six weeks, but he ended up staying with the surrogate family for two and a half years, John Daverio writes in "Robert Schumann." And even though Robert was comfortable with Frau Eleonore Carolina Elisabeth Ruppius and held no qualms over her abilities as a caregiver, even referring to her as his second mother in the autobiography he wrote when he was 15 (per Peter F. Ostwald's "Schumann"), the absence of his own mother was still noticeable to the young Robert. Later, Robert wrote of how he was frequently unable to sleep, recalling one night in particular when he "sat at the window, crying bitterly, so that early in the morning they found me, asleep, with tears rolling down my cheeks."

Deaths in the family

When Robert Schumann was born, he had four older siblings: Eduard, Carl, Julius, and Emilie. But when Robert was just 15 years old, his sister Emilie died by what is believed to be suicide at the age of 29. According to "Schumann" by Peter F. Ostwald, reports vary as to how Emilie died, but her death is generally accepted to have been by suicide. Signs of mental illness are referred to in writings about Emilie, describing "a relentlessly progressive emotional illness [that revealed] occasional traces of quiet madness." This wasn't the first suicide in the Schumann family, with Schumann's grandfather's cousin, George Ferdinand Schumann, having died by suicide in 1817.

On August 10, 1826, about 10 months after the death of his sister, Robert's father Friedrich Schumann died at the age of 53. Robert was devastated, and it was in response to his father's death that he started keeping a diary, which he continued to keep throughout his life, to resist "painful hours eating up the memories of happier times."

Schumann's hand

In 1830, Robert Schumann went to Leipzig, Saxony, to study piano with German piano teacher Friedrich Wieck. Schumann lived with Wieck and started practicing piano up to seven hours every day, hoping to become one of the greatest pianists of their time. But within a year, Schumann started to experience pain in his fingers whenever he played. According to Hektoen International, Schumann wrote: "... whenever I had to move my fourth finger, my whole body would twist convulsively and after six minutes of finger exercises I felt the most interminable pain in my arm, in short a complete breakdown."

In an attempt to push through the pain, Schumann created a finger-strengthening machine using a cigar box, reports WQXR, which kept one finger stationary while forcing the others to move. Unfortunately, all this did was paralyze two of his fingers, with Schumann writing that they "seemed really irreparable."

Schumann tried various treatments ranging from diet to electrotherapy to get his fingers working again, but his career as a pianist was over before it had even begun. He even tried an animal bath, also known as Tierbäder, which involved putting one's hand into the warm abdomen of a slaughtered animal. Not only did none of these treatments work, but in "Schumann," Peter F. Ostwald writes that the animal bath may have caused additional hypochondria in Schumann, as he subsequently wrote of his fears that "something of the cattle-essence might get into my system."

Illnesses and more death

The Schumann family managed to avoid tragedy for several years until Robert fell ill with malaria in July 1833, as did his sister-in-law Rosalie Schumann, who was married to his brother Carl Schumann. Meanwhile, Robert's brother Julius Schumann was chronically ill with tuberculosis and was growing progressively worse. According to "Schumann" by Peter F. Ostwald, Robert had previously visited his brother Julius every time he'd been knocking on death's door. But this time, Robert was too ill to travel. And unfortunately, while Robert managed to recover, Julius died in August 1833.

The death of his brother Julius threw Robert into a depressive episode and he isolated himself from everyone, devoting himself to writings ranging from poetry to musical essays. But in his isolation, he managed to share his consolidated writings with his brother Carl, who helped him found the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, also known as the New Journal for Music.

But the respite that writing offered lasted only so long when, in October 1833, Rosalie succumbed to malaria. Robert had been very close with her and her death pushed him into a depressive breakdown. After Rosalie's death, Schumann wrote how the night of her death was "the most frightful of my life" and how "at this point, a crucial segment of my life begins. The tortures of the most dreadful melancholy from October until December. I was seized by an idée fixe: the fear of going mad," per "Robert Schumann" by John Daverio.

The first suicide attempt

After the deaths of his father Friedrich, his brother Julius, and his sister-in-law Rosalie, Robert Schumann fell into a deep pit of depression. He was in such pits of despair that in "Schumann," Peter F. Ostwald writes how at least one account states that Schumann attempted suicide during his depressive breakdown in 1833. Echoing the story of how his sister Emilie may have died by suicide, some accounts claim that Schumann wanted to "throw himself out of the window during the night."

Eric Frederick Jensen writes in "Schumann" that although it's unclear whether or not Schumann actually did threaten to throw himself out of the window, he was moved to the first floor of the building and reportedly suffered from a fear of heights for the rest of his life.

This wasn't the only breakdown of Schumann's life. He had two other breakdowns in 1844 and 1854, all characterized by intense depression, generalized anxiety, and panic attacks.

[Featured image by Unukorno via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Becoming a composer

In addition to throwing himself into writing and editing the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik during the 1830s, Schumann also turned his attention towards composition. It was also during this time that Schumann stopped seeking outside lessons, believing that "my entire being rebels against every external influence, and I have to discover things on my own for the first time, in order to assimilate them and put them in their proper place," per EIR Culture.

During this decade, Schumann wrote only pieces for piano and composed what he later considered his best works: Kreisleriana, Fantasiestücke, Novelletten, and Romanzen. But despite being a prolific composer, Schumann struggled to be recognized by contemporary audiences, and his work was frequently considered too radical and avant-garde. Even Hungarian composer Franz Liszt deemed some of Schumann's early works "too difficult for the public to digest," according to "Robert Schumann" by John Daverio. Unfortunately, this view persisted throughout Schumann's life, even from his own publishers, who stated in 1848 that "the market for your compositions is, by and large, rather limited–more limited than you could believe."

In 1840, Schumann briefly moved away from piano compositions and embarked on what became known as his Liederjahr, or year of song, during which time he composed over 160 vocal compositions. His second Liederjahr would come in 1850.

Robert and Clara

When Robert Schumann was studying piano with Friedrich Wieck, he became acquainted with Weick's daughter, Clara Weick, who was 11 years old when she first met Schumann. Some accounts even claim Schumann saw her perform when she was just eight years old. Clara also learned piano from her father and was an exceptional pianist, spending almost her entire life touring and performing. And although Schumann had relationships with many other women, even briefly getting engaged to Ernestine von Fricken, he started pursuing Clara in the mid-1830s.

According to "Frauenliebe und Leben" by Rufus Hallmark, Schumann and Clara were engaged on August 14, 1836. However, Clara's father forbade the marriage and any further contact between them, and even took Schumann to court, attempting to prevent the marriage because of Schumann's financial instability. And although the court eventually ruled that they could marry, continuing legal suits led to Clara and her father communicating only through lawyers and third parties for many years afterward. Their reconciliation wouldn't begin until 1843.

Schumann and Clara were finally married on September 12, 1840. Although Schumann initially tried to convince Clara to give up being a professional pianist, he later ended up helping her with composition and encouraging her work, a marked difference from how other composers treated their wives at the time, Hallmark writes.

Composing through depression

As time passed, Robert Schumann's depression and anxiety continued to worsen. Part of it was because his career felt stagnant under the shadow of his wife, Clara Schumann, who continued to tour and be praised for her talent. Additionally, Robert was working on composing Szenen aus Goethes Faust, also known as Scenes from Goethe's Faust, and working on the final scene exhausted him physically and mentally, John Daverio writes in "Robert Schumann."

During this period of depression, Robert persistently kept composing. 1845 is known as the year of Schumann's "fugal passion," during which time he consolidated everything he'd been learning from studying Bach and wrote "Six Fugues on the Name BACH," Op. 60, using the notes B-flat-A-C-B. Inspired by J. S. Bach, the fugues take on their own Romantic existence and additionally, they are "the earliest significant organ compositions on the name B-A-C-H," according to EIR Culture. It was also during this time that Schumann composed Genoveva, Op. 81, his only opera. Unfortunately, it was only performed a few times in 1851.

The perpetual A-note

By the last years of his life, Robert Schumann started experiencing several auditory hallucinations, ranging from angelic voices to demonic ones and even messages from the dead. When the voices were angelic and friendly, Robert was described as hearing "entire pieces from beginning to end, as if played by a full orchestra," and "Ghost Variations," composed in 1854, is even said to be inspired by some of these auditory hallucinations. But one of the things that Schumann kept hearing, a persistent A-note, may not have been a hallucination.

According to "Tone Psychology" by Carl Stumpf, Robert first mentions persistently hearing an A-note in 1853. Although it's unclear exactly how often the A-note persisted in Robert's ear, Clara Schumann recalled in 1883 that "it was only for a brief period that he always heard one tone." But rather than being an auditory hallucination, it's possible that the persistent A-note was a symptom of tinnitus.

Another suicide attempt

On February 27, 1854, while living in Düsseldorf with his family, Robert Schumann left his home around midday and walked to the Rhine River wearing nothing but slippers and a robe in the rain. And as he crossed the wooden bridge over the Rhine River, Robert stopped and jumped over the railing in a suicide attempt. According to the BBC, had river worker Joseph Jüngermann not been there, Robert would've quickly died in the river, either from drowning or hypothermia. But Robert reportedly even fought against his rescuer, wishing to be only taken by the current.

The day before Robert's suicide attempt, he told Clara Schumann that he wanted to be admitted into a mental hospital, fearing that if he wasn't put into an institution, he might harm her, Donald Sanders writes in "Experiencing Schumann." Clara resisted, but after the suicide attempt, Robert's wish was granted, and he was admitted into a mental institution in Bonn on March 4, 1854.

Two years at the asylum

Robert Schumann spent the last two and a half years of his life at a mental hospital. During this time, he lost the ability to speak and experienced seizures as his mental and physical state declined. The Guardian writes that Robert even went from writing coherent letters to Clara Schumann about shared memories to making alphabetized lists of towns.

Although Clara wrote back to Robert's letters, the entire time that Robert was confined to the mental hospital, doctors would not allow her to see him. Clara only saw Robert again just a few days before he died. German composer Johannes Brahms, a family friend, acted as an intermediary between Clara and Robert. But Interlude writes that it wasn't until June 1856 that Clara really learned from Brahms how bad the situation really was.

Clara was finally admitted to see Robert on July 27, 1856. By then, Robert was "in the throes of pneumonia and barely conscious, [although he] mustered the strength to embrace her and mumble a few words of recognition." He was also in an especially weak state because he wasn't eating enough. And just two days later, Robert died on July 29 at the hospital.

[Featured image by Sir James via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Posthumous diagnoses

When Robert Schumann was admitted into the mental institution, he was diagnosed with psychotic melancholia. Since then, many historians have tried to posthumously diagnose Schumann, with theories ranging from bipolar disorder to schizophrenia. And while The Guardian reports that the theory of bipolar disorder, once called manic depression, is now one of the most popular theories, it's also now widely believed that Schumann's declining mental state resulted from tertiary syphilis.

This theory follows the fact that Schumann first reported a sore on his penis in 1831, which is a symptom of primary syphilis. And according to Hektoen International, the pain that Schumann experienced in his fingers when he was studying piano may have been caused by the mercury treatment that was used against syphilis at the time.

But ultimately, the quest to posthumously diagnose Schumann is a quest for the holy grail. And any diagnostic hypothesis will say more about society and its own understanding of mental health than about Schumann's actual mental health. And as biographer Judith Chernaik says, "The music speaks for itself; there's nothing that needs to be diagnosed in psychiatric terms about the music."

[Featured image by Vwpolonia75 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0 Germany]