The Bill Of Rights: How The First 10 Amendments Came To Be

It's a rare American who hasn't learned at least a little about the first 10 Amendments to the Constitution, better known as the Bill of Rights. Most are able to remember some of the features of the First Amendment (which outlines the rights to free speech and religion, among others) and most also know the Second Amendment well enough to understand the ubiquitous quip, "I'm not sure I can tell you word-for-word what the Second Amendment is ... But I'll take a shot at it!"

After that, however, people may be unsure. There's the Third Amendment, which prevents the government from housing soldiers in people's homes. You'll be relieved to know that this is the least litigated amendment and one on which the Supreme Court has never had to offer an opinion.

Many of us take these rights for granted today, but the process of creating the Bill of Rights was a struggle — perhaps more than you may realize. The origins of the Bill of Rights stretch back to medieval England, with ideas that were later developed under the colonialist government of Britain, a kind of Big Brother figure to the United States. The amendments that were ultimately created were critical to the foundation of the American government and its traditions of liberty. Let's look now at how the American Bill of Rights came to be.

It begins with the English deep state

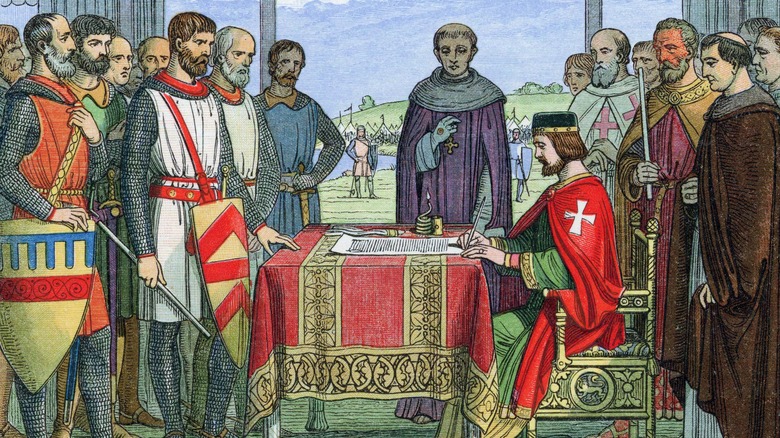

The freedoms in the Bill of Rights were not the brainchild of James Madison alone, but come from a long tradition going back to the medieval English "deep state." In 1215, English barons determined to maintain their power forced the unpopular King John to sign the Magna Carta. This document was hardly what you would call progressive — items like freedom of speech or of the press never crossed the barons' minds. Still, the Magna Carta was a step in the right direction. It limited the monarch's power to tax and granted due process to free men.

Another milestone was 1689's English Bill of Rights which limited the monarch's power even more. This time, the issue was religion and its tie-in to royal succession, since for much of the 17th century, the British were at one another's throats over which brand of Christianity to follow. Parliament settled the matter by inviting the Protestant King William III and Queen Mary II to London to take the throne. In exchange, they just needed to sign the dotted line and give some royal prerogatives away. Since it was their chance at the throne they went ahead and did so in what has been coined the "Glorious Revolution." The English Bill of Rights emphasized the supremacy of Parliament, gave freedom of speech to its members, and emphasized free elections.

Colonists felt entitled

Starting in the 17th century, many Englishmen were disturbed by disruptions in the country. Some residents wanted religious freedom, some wanted to get out of poverty, and some wanted to get away from the violence. They started migrating to America in droves. With them came the sense of entitlement for the English liberties they had grown up with. Each colony learned to operate largely on its own, and the colonists, enjoying the freedom of being an ocean away from the king, seemed happy with the system.

The good times ended when, in the 18th century, the British government decided to make some money from the colonists. This all led to the American Revolution — which was essentially fought over taxes but had its roots in much deeper principles than money.

When the colonies first broke off to form the United States, representatives drew up the country's first constitution, the Articles of Confederation. This document essentially set up 13 sovereign but allied countries with a very feeble central government.

This was done on purpose since the Americans were very sensitive (paranoid even) to the idea of a big government that trampled people's rights (like Britain). But the Articles went too far and made the country largely ineffectual. For example, the central government only got funding from voluntary state contributions, basically making it a charitable organization. The country was in chaos. This led to the creation of today's U.S. Constitution.

The Constitution did not grant enough individual rights

In 1787, various delegates met in secret in Philadelphia to fix the Articles of Confederation. However, the document proved to be beyond hope, so they decided to scrap it and create an entirely new Constitution — the one we know and puzzle about today. The Constitution, when it was written, provided the framework and rules for the government, but it hardly addressed individual rights. Sure, it banned Congress from passing laws that found you guilty of a crime and punished you without trial (called bills of attainder) as well as making things you have done in the past illegal (ex post facto laws). The Constitution also guaranteed that each state would have a smaller form of government.

But bills of attainder and ex post facto laws hardly create the same stir of human emotion as, say, guarantees of freedom of speech or barring cruel and unusual punishment. This lack of rights in the Constitution really bugged some of the Founders. Remember, some were as dubious of big government as Ron Swanson. What they wanted were guarantees of individual liberty and protections of their natural rights from the government. They didn't want to create a monster that was going to take their freedoms away.

Federalists v. Antifederalist

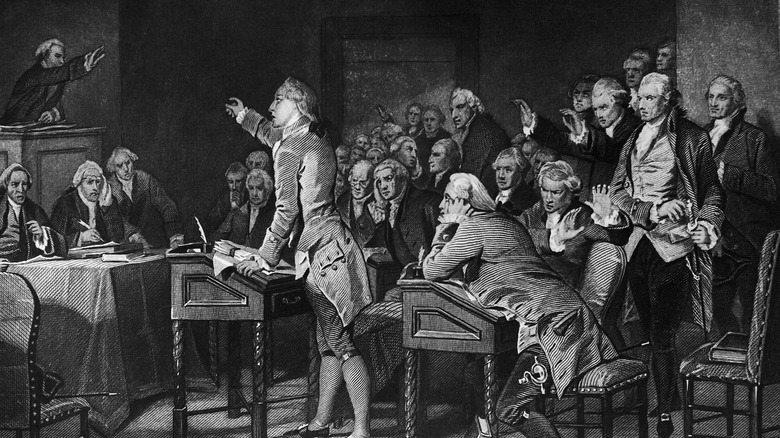

After the Constitution was approved by the Founders, it went out to the different states for full approval. That's when the non-Fourth of July fireworks began. People broke into two factions: Federalists and Antifederalists. Federalists were those who supported ratifying the Constitution as-is, while Antifederalists opposed it. It can best be described as a dispute between nationalist, strong-government ideals (Federalists) versus small-government philosophies (Antifederalists).

Antifederalists in particular were hung up on a lack of any semblance of a bill of rights. For example, Patrick "Give-me-liberty-or-give-me-death" Henry made a speech in 1788 stating, "(O)ur rights and privileges are endangered, and the sovereignty of the states will be relinquished: And cannot we plainly see that this is actually the case? The rights of conscience, trial by jury, liberty of the press, all your immunities and franchises, all pretensions to human rights and privileges, are rendered insecure ..."

Another Antifederalist, George Mason, declared that without a Bill of Rights, the new government could "... accomplish what usurpations they please, upon the rights and liberties of the people." Mason, in fact, tried to get a Bill of Rights inserted at the beginning of the Constitution during its drafting. It was voted down 0-10.

James Madison meh on a Bill of Rights

Did this mean that the Federalists, such as Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison were against individual rights? The answer is no. They simply thought the idea of a Bill of Rights was silly at best and dangerous at worst.

One of the great ironies of the Bill of Rights is that its main author, James Madison, seemed indifferent to them. The National Archives quotes Madison as writing, "(T)he government can only exert the powers specified by the Constitution." By this, he meant that the government as designed can only exercise the powers expressly given to it. Therefore, it couldn't take away your rights. Looking back with hindsight, you might guess how that could have turned out.

Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, authored The Federalist Papers – a collection of essays that promoted ratifying the Constitution with no strings attached. The issue of the Bill of Rights is specifically addressed by Hamilton in Federalist No. 84. Hamilton pointed out that bills of rights such as the Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights were agreements between a king and subjects. Hamilton argued that bills of rights do not apply "... to constitutions professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants. Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing; and as they retain everything they have no need of particular reservations."

John Hancock saves the day

It looked like the standoff between the Federalists and the Antifederalists was going to be the death knell for the Constitution, especially when Massachusetts prepared to reject it. However, just at that moment, the Founder with the most prominent signature — John Hancock — signed off. Hancock, who represented Massachusetts, is described by the Center for the Study of the American Constitution as a vacillating politician who engaged in "fence-straddling," but not necessarily in a bad way.

In October 1787, Hancock declared, "It not being within the duties, of my office to decide upon this momentous affair." However, after recovering from an illness on January 31, 1788, he declared his support for the Constitution and said it should be ratified without a Bill of Rights. Hancock made a speech during in Massachusetts stating, " (A) general system of government is indispensably necessary to save our country from ruin." He added, "I give my assent to the Constitution, in full confidence that the amendments proposed will soon become a part of the system."

However, there was one caveat. Massachusetts would submit recommended amendments that would form a Bill of Rights and it was understood there would be one. This became known as the "Massachusetts Compromise," and it saved the Constitution. Because of this, James Madison began to change his tune on the matter of the Bill of Rights, with the additional cajoling of Thomas Jefferson.

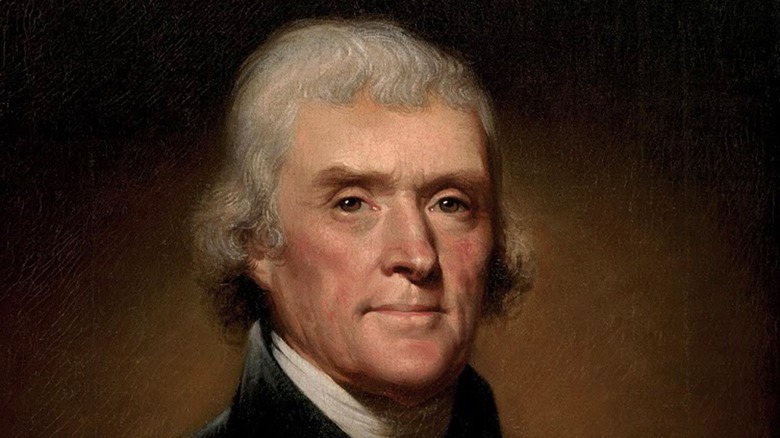

Thomas Jefferson steps in

Thomas Jefferson, who had the revolutionary cred of writing the Declaration of Independence, threw in his support. In fact, Jefferson had long supported the Bill of Rights and helped woo James Madison toward supporting it. In a letter transcribed by the Constitution Center to Madison dated December 20, 1787, Jefferson noted that he disliked the "omission of a bill of rights providing clearly & without the aid of sophisms" various individual rights including religion, press, and trial by jury. Later in the letter he added, "(A) bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, & what no just government should refuse or rest on inference."

Madison, for his part, wrote to Jefferson on the matter nearly a year later, on October 17, 1788. He seemed to downplay his own opposition, stating that he has always been in favor of it but admitted that he had not "viewed it in an important light." He also opined that even writing a Bill of Rights may be pointless since "Repeated violations of these parchment barriers have been committed by overbearing majorities in every State." Still, Madison realized that a Bill of Rights was politically important, so he busted out his quill and got drafting.

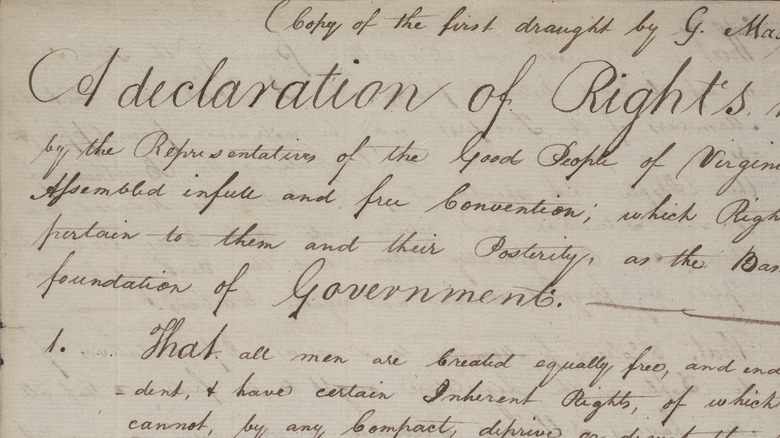

Madison was inspired by George Mason

When working on the initial drafts of the Bill of Rights, James Madison was (of course) influenced by the Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights. However, there were other documents and ideas which may have provided more direct inspiration. The ideas behind individual rights — including the notion of natural rights humans are born with, come from the Enlightenment. In fact, the Bill of Rights is a pure brainwave of Enlightenment ideals of limited government and freedom for the individual.

During the American Revolution, George Mason enunciated these ideas in 1776's "Virginia Declaration of Rights." Among other rights, the Declaration called for freedom of the press, the right to due process, and freedom of religion. Some of the ideas, if not language, from the Virginia Declaration was lifted by Thomas Jefferson for the Declaration of Independence. Likewise, when Madison started drafting the Bill of Rights, he used the language and ideas of George Mason. These he introduced to the first Congress on June 8, 1789.

The Bill of Rights was a whip-syllabub

James Madison's own perspective on the Bill of Rights was a bit milquetoast-y. Or at least, he was hard-nosed to the idea that he needed a Bill of Rights to pass the Constitution. Madison emphasized how his Bill of Rights was a fundamental necessity to preserve the body politic, essentially saying he thought it was good PR. In a speech he made before Congress, when submitting the Bill of Rights, he said they only needed one day to debate the subject to "satisfy the public that we do not disregard their wishes." He further stated, "We ought not to disregard their [the public's] inclination, but, on principles of amity and moderation, conform to their wishes, and expressly declare the great rights of mankind secured under this constitution."

Antifederalists were suspicious that these amendments were meant to draw attention away from criticism of the Constitution. Antifederalist Thomas Tudor Tucker stated that the amendments were, "(C)alculated merely to amuse, or rather to deceive." Another Antifederalist, Aedanus Burke, quipped, "They are little better than whip-syllabub, frothy and full of wind, formed only to please the palate ... In my judgment the people will not be satisfied." In case you were wondering, according to Merriam-Webster, a "syllabub" is a "milk or cream that is curdled with an acid beverage (such as wine or cider) and often sweetened and served as a drink or topping or thickened with gelatin and served as a dessert"

The Bill of Rights was born on the Ides of December

The Bill of Rights as it exists today consists of 10 amendments. But when James Madison submitted his first draft, there were 17. So wait, does that mean that there were seven additional rights that you should have that never got approved? Not really.

On August 24, 1789, the House of Representatives passed all the proposed amendments. These then went to the Senate which then consolidated the list down to 12. For example, the 10th Amendment, which states that powers not delegated by the Constitution to the government (or prohibited from being used by the states) are reserved for the states or the people, originally reserved power only to the states. The Senate's marked-up version, as provided by the Library of Congress, has a handwritten insertion at the end saying "or to the People."

So 12 articles went out to the states for final ratification. Of these, amendments three through 12 were approved by enough states to become law on December 15, 1791.

There were two amendments too many

Since the states had only approved 10 of James Madison's 12 articles, does that mean that American citizens were denied certain rights Madison meant them to have? Not necessarily. The two articles in question did not have to do with individual rights.

The first article the states voted down had to do with how many people a representative represents. The U.S. Senate's summary says, had Madison's amendment gone through, each congressional district was to be capped at 50,000 citizens. That may have been fine for the population shown in the 1790 census of nearly four million, but the population of the United States in the 2020 census was well over 331 million people. Using Madison's formula would have resulted in over 6,600 representatives. One can imagine the exponential increase in governmental dysfunction. The proposed amendment failed.

Madison's second article was an anti-corruption measure. It stipulated that pay increases for Congress can only go into effect after an intervening election. The purpose was to allow the voters to register their opinion regarding Congressional pay. What is interesting about this amendment is that since there was no time limit set on it for when approval from the states had to be made, it actually was fully approved by the requisite number of states over two centuries later in 1992. It now is enshrined in the Constitution as the 27th Amendment.

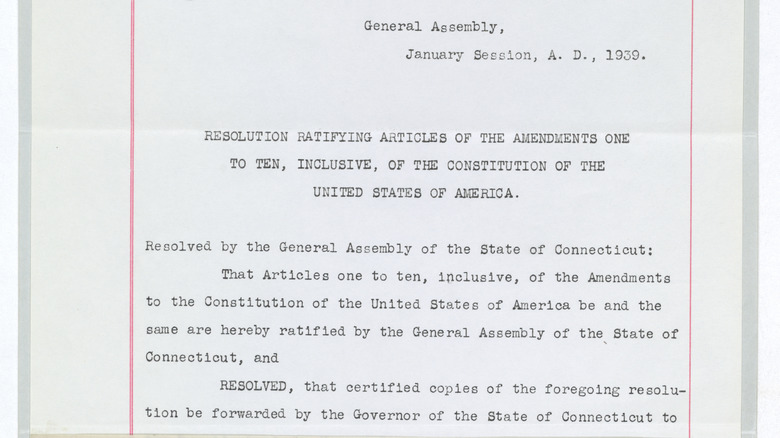

Not all states wanted or approved the Bill of Rights

To approve a Constitutional amendment, three-fourths of the states need to ratify it. That means that there could be some states that don't want a particular amendment but have to accept it anyway. Amazingly, there were states who did not ratify the Bill of Rights.

After Virginia submitted its approval on December 15, 1791, the requisite number of states needed to approve the Bill of Rights was reached, according to the National Archives. At the time, the states of Georgia, Connecticut, and Massachusetts had not ratified the amendments. Georgia, in fact, had rejected them altogether on the grounds that a Bill of Rights was premature since the new Constitution should be tried out for a while. As for Connecticut and Massachusetts, there had been a lack of agreement on which of the twelve amendments to approve, and the outcome wasn't clear.

Either way, the Bill of Rights did get approved and became enshrined in American history, politics, and culture. In 1939 — the 150th anniversary of the Constitution — the three states, which were no doubt somewhat embarrassed at not having approved the Bill of Rights, approved them symbolically.