Female Archaeologists Who Changed History Forever

Archaeologists bring to light evidence of humanity's past. Archeology is the study of our species over time, using material evidence like artifacts, large structures, or even remains to learn more about humans and human ancestors.

Ever since archaeology began as a field of study in 18th-century Europe, it's been a seriously male-dominated discipline. Even as some barriers, such as rampant sexism and lack of access to education, have eroded, it's still all too common to come across excavations with very few women involved. As archaeology professor Lisa Overholtzer told The Tribune, there are plenty of qualified female archaeologists out there, but many are so beset by ingrained biases and other pressures of academia that they drop out of the field just when they might be making a visible difference in the gender makeup of a department.

While it's unlikely that anyone will find an easy fix for the insidious, often unacknowledged sexism in this and other academic fields, it's not all bad. We can still take heart in the stories of intrepid women who forged ahead in archaeology. Some started with a leg up in terms of social class or access to funds, while others persisted in their love of the field even when record keepers could barely be bothered to remember their names. All have made their mark on history, quite often literally, as they uncovered evidence of past people and civilizations.

[Featured image by UCL Institute of Archaeology via Wikimedia Commons|Cropped and scaled|CC BY 4.0]

Dorothy Garrod

When it comes to influential female archaeologists, Dorothy Garrod is impossible to ignore. Born as the upper-class daughter of an Oxford professor of medicine, Garrod turned to prehistoric archaeology after the deaths of her brothers in World War I. What may have begun as an academic distraction from her grief soon became a serious professional pursuit. Garrod went on to attend the University of Oxford, then began excavations at Paleolithic sites in Gibraltar and Kurdistan in the 1920s.

But the excavation that made the biggest splash was probably her work conducting research at Palestine's Mount Carmel caves in 1931 and 1932. With the help of a largely female team of Palestinian excavators, Garrod found evidence of about a dozen individuals, including a Neanderthal female now known as Tabun 1 whose remains date back at least 50,000 years. Accounts of the team at Mount Carmel note that, unusually for the time, women were more likely to take on the interesting, intellectual work, while men undertook more repetitive labor.

Towards the end of her career, Garrod turned to more traditional academic work, becoming the first woman to hold a chair at Cambridge when she became the Disney Professor of Archaeology at the university in 1939.

Yusra

It's relatively easy to talk about archaeologists who have started with some sort of advantage. While not everyone has the benefit of rich parents or an Oxford-level education, it's certainly easier to get one's name recorded with a college degree and some important professional connections providing a headwind. Yet, while privileged archaeologists have certainly undertaken important work, their stories aren't the only ones worth telling.

Take Yusra. Though no one's been able to uncover her family name, it's clear that she was a vital member of English archaeologist Dorothy Garrod's excavation of the Mount Carmel Caves. This site, with its wealth of prehistoric material, was examined by Garrod and her team in 1920s and 1930s British-held Palestine. Many excavators in Garrod's team were local women who undertook both the physical labor of digging and carefully noting all their finds.

Yusra earned particular respect for her ambition (she reportedly wished to attend Cambridge) and a uniquely keen eye, a very useful talent in a site where bones and stone were intermixed and often hard to tell apart. But Yusra certainly could. In 1932, she spotted a single tooth that led to an entire skull of a female Neanderthal. It was an astonishing find that uncovered more information about the human ancestors living in the region more than 100,000 years ago. Yet, after Garrod's excavation concluded, there is little information about what happened to Yusra, though the region was hit hard by the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Margaret Murray

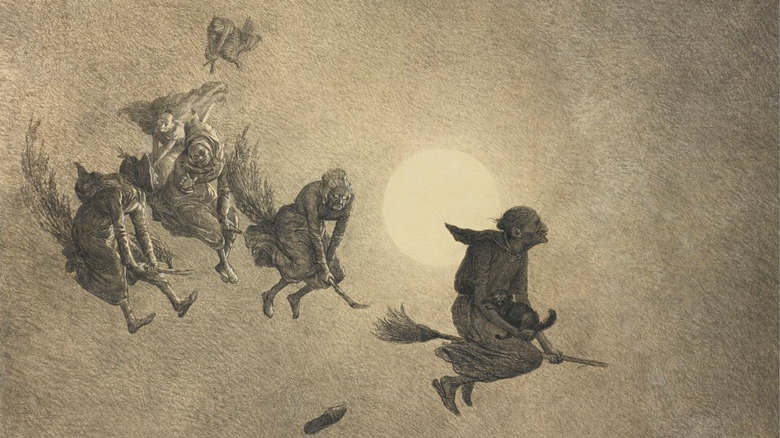

Margaret Murray was, at one point in time, both a pretty well-regarded archaeologist and the foremost authority on the history of witchcraft. Despite spending part of her childhood under the care of an uncle who assumed women were lesser than men and wanted young Margaret to know her place, Murray eventually became an archaeologist. What's more, she wasn't an also-ran relegated to the sidelines. Instead, Murray became popular amongst both the general public and respected by her academic peers.

Her 1921 publication of "The Witch-Cult in Western Europe" certainly seemed authoritative. In its pages, Murray — barred from excavating in Egypt due to World War I — drew upon the records of witch trials to tell the story of European witchcraft, with set holidays, rituals, and worship of a mysterious, compelling horned god. Her groundbreaking research eventually fed into the revival of modern witchcraft, especially in the form of Wicca.

Today, however, Murray's work has been called into question. While the idea of secret witches in medieval Europe was exciting, Murray's use of torture-induced confessions undermined her conclusions. She also seemed willing to take the barest wisps of evidence and spin them into grand theories. Yet, judging by both the spread of Wicca and the growing academic study of witchcraft, it's hard to deny her influence, even with its undeniable flaws.

Shahina Farid

When it comes to archaeological sites, Çatalhöyük is nothing short of jaw-dropping. Located in modern Turkey, it's one of the earliest human settlements that could be called a city, with an expanse of closely-grouped homes and evidence of artwork and complex religious beliefs. It was first occupied in the Neolithic period starting around 7,400 BCE and, after the passage of many centuries, was first excavated in the 1960s by archaeologist James Mellaart.

While Mellaart can claim the first survey of the site, another archaeologist has had far more time at Çatalhöyük. In 1995, British archaeologist Shahina Farid joined the ongoing excavations at the site as field director. There, she not only managed more than 200 people at the site but also had a key role in outlining the different layers of the long-inhabited city, an exacting process known as stratigraphy. Without that sort of exacting work, much of the research that's been published about Çatalhöyük wouldn't have a leg to stand on — or, it simply wouldn't exist in the first place.

Gertrude Caton-Thompson

Gertrude Caton-Thompson ran in the sort of circles that sent young girls to Parisian schools and went on family trips abroad. It was on just such a tour that things began to deviate from the norm for Caton-Thompson, when Rome proved so interesting that she couldn't get it out of her head. Despite all of the leisurely activities and social events that were de rigueur for young women of the time, things soon changed. By 1911, she was an active participant in the women's suffrage movement. Just a few years later, she was also supporting Britain's role in World War I.

Perhaps, with such weighty issues in front of her, a lifetime of playing tennis and attending concerts just wasn't going to cut it for Caton-Thompson anymore. By 1915, she was volunteering at an excavation in Menton, France, returning in 1921 before joining a British archaeological expedition in Egypt that year. Eventually, she began conducting her own excavations in Egypt with a focus on Stone Age cultures.

Caton-Thompson's biggest work started in 1929 when she began excavating the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, a medieval city in what's now southern Zimbabwe. Her rigorous work there — with an all-female team, no less — showed that Great Zimbabwe had far-reaching trade ties and monumental architecture that had been built by African people. It was a controversial find at a time when colonial interests wanted to push such histories under the rug, but Caton-Thompson's evidence was all but impossible to deny.

[Featured image by Andrew Moore via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Kathleen Kenyon

In the world of Biblical archaeology, Kathleen Kenyon simply cannot be missed. She got her start as a photographer on the 1929 excavation of Great Zimbabwe under the direction of Gertrude Caton-Thompson. She then returned to her native Britain to excavate ancient sites there, eventually coming to work with the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London from 1935 to 1962. It was through these connections that she also became director of the British School of Archaeology, based in Jerusalem, a move that allowed her to excavate the site of the city of Jericho from 1952 to 1958.

Though Kenyon would have already secured her reputation without it, the excavation of Jericho turned her into an icon of the field. Her careful examinations of the site showed that Jericho is one of the oldest cities in the world, with signs of habitation going all the way back to 9,000 BCE. Kenyon wasn't the first to dig there, but her work was regarded as highly scientific and meticulous, with dramatic finds like evidence of burned structures, giant walls, and human skulls with plaster casings in the shape of living human faces.

Kenyon's dedication to the science of her work meant that she went against the commonly-accepted Biblical accounts when the evidence pointed elsewhere — likely a tough proposition for a believer such as Kenyon. She was also an early proponent of stratigraphy, the careful analysis of different soil layers that is utterly key to modern archaeology.

Honor Frost

The popular conception of archaeology — at least, once you get past the entertaining but highly inaccurate antics of Indiana Jones — is of a piece of land somewhere, with people carefully removing layers of soil and other debris as they uncover past traces of our species. But why stop there? Some archaeologists have left dry land entirely, donning wetsuits for the adventurous pursuit of underwater archaeology. Spend even a small amount of time reading into this subfield, and you'll certainly come across Honor Frost.

Frost wasn't just the owner of a cool name. She was also a distinguished scientist who proved to be a key figure in underwater archaeology, starting her work in the 1950s by making detailed records of Mediterranean shipwrecks. Early in her career, she studied under Kathleen Kenyon at the remnants of ancient Jericho in what's now Jordan. Though the Jericho excavation was definitely on dry land, Frost took the skills she developed there in drawing detailed plans and applied them while surveying an ancient wreck off the coast of Turkey. Thereafter, underwater archaeology went from simply diving around cool wrecks to a serious, scientific study.

[Featured image by Editsicinf via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Sada Mire

All too often, archaeologists are depicted as thoroughly stuck in the past, with no real connections to the present. But that's hardly the entire story. Many archaeologists recognize that evidence of the past can be very important to humans who are alive today. A growing school of thought in heritage management maintains that people in a modern community ought to be able to control and preserve the archaeological evidence of their ancestors. It certainly shouldn't be excavated, packed up, and placed in museums thousands of miles away.

These ideas are central to the work of Sada Mire, a Somali archaeologist who fled her home country in the 1990s. On the road to earning her Ph.D., she became committed to returning to Somaliland (a state officially considered part of Somalia but which declared itself independent in 1991). The region has since been beset by conflict, but Mire maintains that the peoples' heritage is still vital and worth preservation. Beyond helping to preserve sites and empowering local people to manage them, Mire and her team have uncovered evidence of ancient rock art calendars in Somaliland.

Mire told Sapiens that her work is especially important given how much of African archaeology has been neglected for generations. She also argued that indigenous ways of understanding the past and culture needed to be incorporated into an otherwise very Westernized model of archaeology.

Gudrun Corvinus

Though most archaeologists will be put off if you ask how their dinosaur research is going (that would be the domain of paleontologists), German archaeologist Gudrun Corvinus would have been able to provide a more complicated answer. That's because she started as a paleontologist working with fossil ammonites, though she made a rather fateful decision to study early humans relatively soon in her career.

Though Corvinus' name may not ring bells in the same way as that of the famous Leakey family, do a bit of digging and you'll see that she was part of major archaeological finds across the globe. Not only was she part of the team that uncovered the famous "Lucy" fossil (of a bipedal human ancestor known as Australopithecus afarensis) in Ethiopia's Hadar Valley, but she made the first Stone Age finds in the same region. And don't discount Lucy just because of her cute name. When her bones were excavated in late 1974, the team that included Corvinus found that the australopithecine's remains were 40% complete — a pretty astounding figure when you consider the fact that Lucy died more than 3 million years ago. Studies of her fossils and others of her species provided important information about human ancestors, especially how we became upright bipedal walkers.

Gussie White

Gussie White was one amongst several women who worked on the Irene Mound site near Savannah, Georgia in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It consisted of a series of mounds that had been used by native people for centuries alongside the Savannah River, with peak use from around the 12th to 14th century. Excavations revealed burials and a small residential quarter, most likely meant for chiefs and their family and associates. Anyone wanting to visit the site nowadays is bound to be disappointed, however. That's because the site is now occupied by ship docks.

Though whatever was left of Irene Mound is now buried beneath a state port authority operation, the legacy of the site and excavators like Gussie White remain. As John White told researcher Gail Whalen (via The Georgia Historical Quarterly), his mother came to take part in the Works Progress Administration-funded Irene Mound project after an accident left her husband unable to work. Despite the conditions, workers were given next to no protective equipment and were photographed wearing ersatz work clothes or even everyday gear. Though racist and sexist attitudes of the time worked continuously to demean the work of White and her co-excavators, it's clear that little would have come of the project without their physical labor and keen eyes.

White was also a distinguished Civil Rights activist who encouraged her son, John, to become one of the first Black police officers in Savannah in 1947.

Mary Leakey

When it comes to archaeologists, and paleoanthropologists in particular, you just can't get away from the Leakeys. Known for their excavations in East Africa, many in the family are connected to the discovery of early human ancestors. Louis Leakey certainly gets plenty of credit for his work in Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge, which revealed evidence of hominids now known to be part of the Paranthropus lineage.

But his wife, Mary Leakey, was more than a scientist's spouse. She was a respected archaeologist in her own right, who was known to be a better excavator than Louis. As a young girl, Mary was ready to break with tradition, to the point where she was expelled from two convent schools (the second time for reportedly exploding a chemistry lab). She eventually settled down somewhat and got her start in archaeology while working at sites in Britain. She gained serious scientific fame in 1948 when she uncovered the remains of a 25 million-year-old human ancestor, Proconsul africanus.

As if that weren't enough, Louis' big to-do about Paranthropus was thanks to her. Mary was the one who, in 1959, spotted the skull that was key to all the later work. Oh, and Mary also uncovered another human ancestor, Homo habilis, in 1961. And in 1976 and 1977, she continued her habit of major finds with the discovery of the Laetoli footprints. She kept working for decades longer, further cementing her reputation as an absolute legend in the world of paleoanthropology and archaeology.

Margaret Guido

The 7th-century figure who was placed in Britain's Sutton Hoo ship burial was laid to rest surrounded by treasure, including a sword, armor, and the fragments of a spectacular bejeweled helmet. It was uncovered just ahead of World War II, by a team first headed by dedicated amateur archaeologist Basil Brown.

At certain points, you would have been able to look into the excavation pit and see a woman. Her name at the time was Cecily Margaret Piggot, though she was known as Peggy. By the time she joined the Sutton Hoo dig in 1939, she was an established archaeologist with a Cambridge degree, academic papers to her name, and a reputation as an excellent excavator.

Though Peggy deserves recognition for finding some of the first bejeweled bits from the Sutton Hoo treasure, her career went far beyond excavating bits of a sword or a glittering belt buckle. She was in charge of numerous World War II-era excavations, recording evidence at sites before the British government took them over for wartime activities. After the war, she continued her work uncovering more of Britain's prehistory and, after marrying her second husband, worked in Italian archaeology for a time. Piggott also became well-known for her study of ancient glass beads in Britain, becoming a subject expert. And, far from being a one-off member of a famous excavation, Piggott proved that she could readily stand on her own, with a stupendous career that spanned six decades until she died in 1994.