The Symbolism Behind The Objects Used In British Royal Ceremonies

Coronations in Britain — the last nation in Europe to still practice the ritualistic crowning of a monarch — are stuffed with meaning. The coronation itself is symbolic. Alone, putting a hat on is nothing special, even if it is studded with gemstones. But the point of a coronation is to formally invest a sovereign with the powers and responsibilities of their royal position, represented by the crown. Folded into the mix is an oath of office for the head of state and an Anglican service to bestow the grace of God upon the monarch.

The oath may not have a physical object to accompany it, but the anointing ritual (called the unction, according to the House of Commons Library) makes use of holy oil and its vessels. Other symbols of royalty, tied to different rights, obligations, and expected virtues, also come with the crown during a coronation. Some of these objects have additional meaning that sees them broken out at other ceremonial state functions throughout a monarch's reign. Here are a few of the objects used by the British royal family, and the meaning behind them.

St. Edward's Chair

The throne used by British kings and queens during their inauguration is one trapping of royalty that can verifiably be traced back to medieval times. It is known as the Coronation Chair or St. Edwards Chair, though whether the image of a king painted on the back was intended to be Edward the Confessor or Edward I, Longshanks, is unclear. It is known that Edward I was the king who commissioned the throne between 1300 and 1301 (per Westminster Abbey). It wasn't built for a coronation, however, but to house plunder.

The prize Edward kept in the chair was the Stone of Scone, said to be the rock Jacob rested his head upon at Bethel in Genesis. It was used as the seat on which Irish and later Scottish kings were crowned (and is said to stay silent at pretenders), until Edward seized it in 1296. The Stone remained housed beneath the chair for centuries, used in English and British coronations beginning with Edward II, until it was removed for safekeeping during World War II. Scottish nationalists briefly got hold of it in the 1950s, and in 1996, it was decided to return the Stone to Scotland.

At over 700 years old, the Coronation Chair has been subject to graffiti, weathering, and bomb damage. Ahead of the coronation of Charles III in 2023, it underwent extensive renovation to be ready for the ceremony.

The two crowns

For all the other words and rituals it involves, a coronation is centered on the act of putting a crown onto the head of a monarch. The modern British coronation makes use of two different crowns. The one used for the crowning itself is known as St. Edward's Crown and is used exclusively for that purpose. The name "St. Edward's Crown" was first applied in the 13th century, but according to Britannica, the same crown was used in the coronations of every English ruler after Edward I until the crown was dismantled following the beheading of Charles I. The current crown is said to have been made from the recovered pieces of the old one, providing at least an apocryphal link to past dynasties.

After receiving St. Edward's Crown, the monarch traditionally exchanges it for another. The second crown used since George VI is the Imperial State Crown, made with a gold frame that supports thousands of individual jewels. Several of these are legendary stones in British history. Four of the pearls are tied to Elizabeth I by myth, if not by fact; a spinel is alleged to be the Black Prince's Ruby; and the sapphire in the crown is said to come from the ring of St. Edward the Confessor.

The Imperial State Crown sees other uses beyond the coronation. Elizabeth II regularly wore it to the state opening of Parliament, and it was mounted on her coffin for her funeral.

The Sovereign's Orb

Besides the crown, another common symbol of royalty is the orb mounted with a cross, sometimes referred to as the imperial apple. Per Britannica, the association of kingship with some sort of ball goes back to Roman times. The emperors of Rome were seen as emissaries of Jupiter, king of gods and lord of the cosmos, and the orb was a symbol of his realm. With the rise of Christianity, depictions of the orb began to include crosses to reflect the new faith. Such orbs became part of European coronation ceremonies after Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor, used one in 1014.

The Sovereign's Orb, as the object used in British coronations is known, was built in 1661 for Charles II (per the Royal Collection Trust). It is a hollow gold ball with bejeweled bands that split it into the three known continents of the medieval world. The cross on top is mounted on an amethyst and decorated with diamonds around an emerald on one side and a sapphire on the other. When it is given to a monarch during the coronation, they receive it in their right hand before placing itupon an altar.

The Sovereign's Scepters

Separated from their intended meaning, some of the accouterments of monarchy can seem strange — holding an elaborate stick, for instance. But the scepters of royalty have been traced back to the ancient Greeks and Germanic tribes, who used staffs and wands in crowning their rulers to symbolize various powers and responsibilities. It became common to use two scepters for coronation ceremonies during the 10th century, but outside of England, the orb replaced the second staff. Today, the U.K. makes use of all three symbols.

The Sovereign's Scepter with Cross, originally built in 1661 but extensively modified over the centuries, is notable for housing the Cullinan I diamond, the largest known cut diamond in the world. The scepter's true purpose, however, is to symbolize earthly authority and able rule (per the Royal Collection Trust). It is paired with the Sovereign's Scepter with Dove, also built in 1661, which signifies mercy and the sovereign's ties to spirituality and religion. Kings and queens receive the two scepters together, after being invested with the rest of the symbolic ornaments but before being crowned.

The Coronation Spoon

Crowns, robes, orbs, scepters — centuries of depictions of kings and queens have made these objects readily associated with monarchy, even if a viewer doesn't understand their exact meaning. But why would a monarch need a fancy spoon during their coronation? Can the royal lips not handle the touch of common silverware at dinner? The Coronation Spoon, as it is formally named, isn't for eating, but for the unction.

The engraved silver-gilt spoon, created in the 12th century, is paired with a golden, eagle-shaped vessel called the Ampulla (per the Royal Collection Trust), which holds the holy oil used to anoint the monarch during the coronation. The practice of anointing rulers to tie them to God is traced to the Old Testament description of Solomon, and was later used to reinforce the notion of divine right. Since the sovereign of Britain is also the supreme governor of the Church of England, the unction still provides a more direct tie to organized religion. The spoon receives the oil from the ampulla, and the archbishop anointing the monarch takes oil from the spoon to mark the head, hands, and breast.

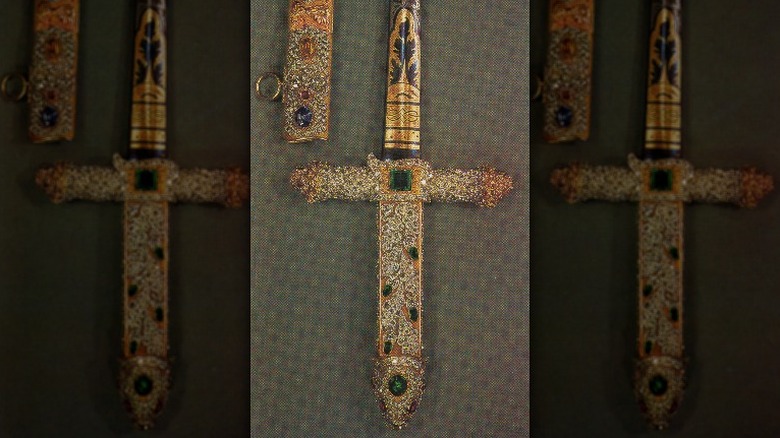

The swords

Personally leading soldiers into battle has long since been phased out of the list of monarchial duties, as has the expectation that they display great martial prowess. But swords still feature prominently at royal ceremonial functions, to represent different aspects of monarchial rule. Among them is the Sword of Offering, a heavily decorated blade with an equally elaborate scabbard. It's one of the objects that a monarch receives before being crowned, with the sword representing the authority and duty to protect good and punish evil.

Three swords are carried during the coronation procession, with their scabbards off and tips up. Two of these are the Swords of Justice, one for the monarch's role as leader of the British military and one for their role in defending the Church of England as Defender of the Faith. They are carried alongside the Sword of Mercy, also known as the Curtana. Unlike the others, the Curtana has a blunted tip, to better represent mercy. These three swords have been in use for royal coronations since the time of Charles I, though using three swords dates back to Richard the Lionheart (per the Royal Collection Trust).

On occasions like the state opening of Parliament, another sword is carried ahead of the monarch, the Sword of State. Broadly representing the monarch's power as head of state, it has been used for a variety of purposes since the 17th century. Queen Elizabeth II used it to invest Charles as Prince of Wales in 1969.

The Sovereign's Ring

It's said that one of Elizabeth I's justifications for not taking a husband was that she was wedded to her country. To emphasize this bond, she allegedly indicated the ring that she was given at her coronation (per The Court Jeweller). That might be stretching the meaning behind the ring, but it has long been a tradition for the monarch to receive a ring as a binding symbol between them and their nation, alongside other objects ahead of their crowning. It was also traditional, until the 19th century, that a new ring be made for each monarch.

Since 1831, coronations have used what's known as the Sovereign's Ring, originally made for William IV. The ring is patterned after the national flag of the United Kingdom, with a red ruby cross for England set over a blue sapphire for Scotland, and a border of diamonds. The only time the Sovereign's Ring hasn't been used, since its creation, was when it proved too big for Queen Victoria. A replica on a smaller scale was made for her, although that one had the problem of being sized for the wrong finger and thus ended up too small.

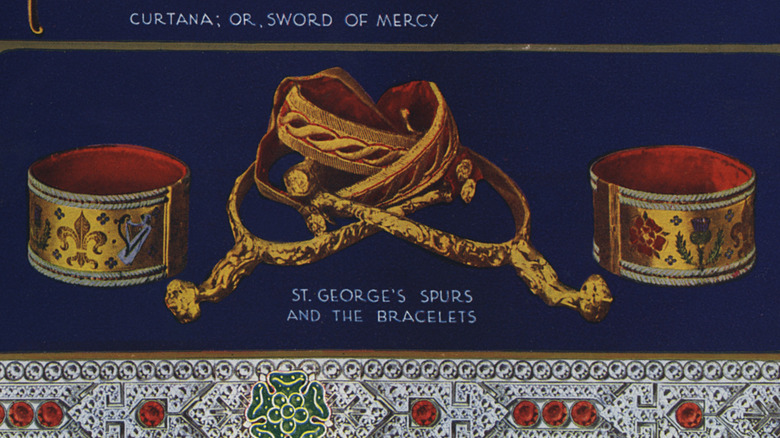

The spurs

Since 1189, British coronations have borrowed from the traditional creation of knighthood and included spurs among the objects of investiture (per the Royal Collection Trust). Besides their practical function, a knight's spurs were a sign that they brought justice and protection with them. Beginning with Richard the Lionheart, a pair of golden spurs were fastened to a monarch's feet during the coronation, but this was done away with after the Restoration. From then on, the spurs have been held against the king's ankles. Even this is waived for queens and their long gowns; for their coronations, the spurs are only shown to them before going on an altar with other objects of investiture.

The spurs currently used in the coronation ceremony were created in 1661 for Charles II and modified into their present form for George IV in 1820. The gold of the spurs finishes in two Tudor rose designs.

The Armills

Along with everything else they receive, a British monarch is clasped with golden bracelets known as Armills during their coronation. Just why this is part of the ceremony is unclear. According to the Royal Collection Trust, the script for the coronation describes the Armills as "bracelets of sincerity and wisdom," but they've also been tied to knighthood, God's protection, and the unity between sovereign and people. Whether the Armills made a regular appearance at coronations after the Restoration is also disputed, with conflicting reports suggesting it may have been confused with a long stole called the Armilla in records.

The last time the Armills were used in a coronation was for Elizabeth II's in 1953, and they were custom-made for her. They were intended as a gift to the queen from several nations in the British Commonwealth. Besides Britain itself, Canada, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Southern Rhodesia, and Ceylon put their names on the present — literally. A message from the governments of those nations is engraved on the bracelets, made of gold and held by a Tudor rose catch. The Archbishop of Canterbury put them on Elizabeth, the right and then the left, and she still had them on when she appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace.