Real-Life People Who Had Medical Conditions Named After Them

Everyone wants to leave their mark on history, and there's no better way to do that than having something important named after you. A bridge? Awesome. A new invention? Great! An obscure scientific theory? Well ... everyone who understands it will appreciate it. It's no different when it comes to the world of medicine and psychology, where long and unique names like Alzheimer, Klinefelter, Münchausen, and Tourette now fly off any nurse's tongue as easily as a kid spouting Latin dinosaur names. While critics oppose the practice of naming medical conditions after people, it's definitely easier for non-medical folks to remember a unique name than a string of letters.

This raises a question, though: What does an ambitious person have to do if they want a medical condition named after them? The answer isn't so clear. Sometimes doctors get the credit, sometimes it goes to a well-known patient, and sometimes, telling a few exaggerated stories will do the trick.

A teenage experience compelled the man who first identified Down syndrome

It sounds cliché, but John Langdon Down's quest to help the developmentally disabled really did begin on a dark and stormy night. As the rain poured down, according to the National Library of Medicine, 18-year-old Down found shelter in a nearby farm. While waiting out the storm, he was helped by an unknown girl with a unique facial appearance he'd never seen before. Though the girl seemed kind and giving, something about her struck him. Driven to understand the girl's condition, Down became a doctor.

Then, to the dismay of his colleagues, Down took over the Earlswood Asylum for Idiots. At this time, the asylum was a complete wreck. Four hundred patients were clustered into small rooms, poor hygiene practices led to frequent infections, and the patients were regularly abused by the staff. Against all the odds, the bright-eyed and ambitious Down turned the place around, largely due to his compassion for his patients. He banned corporal punishment, focused on positive reinforcement, and taught arts and crafts. His achievements were all the more impressive because his position required him to not only be an administrator and a psychiatrist, but also a psychologist, a counselor, and a social worker, according to the Langdon Down Museum of Learning Disability. In 1860, Down finally diagnosed the condition of the girl he'd met as a youth, and 100 years later, the condition was officially named Down syndrome.

Tourette was a big believer in hypnosis

If you think your full name is too long, just imagine being Georges Albert Édouard Brutus Gilles de la Tourette. (You might even curse your name.) Living in a time when people still thought many mental illnesses were caused by demonic spirits, according to the Tourette Association of America, Tourette worked under the guidance of his mentor, Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, and studied a common set of behaviors and tics among nine individuals, which he called "maladie des tics." Tourette probably wasn't the first person to identify this disorder — and he had a pretty weird (and wrong) theory that patient symptoms were caused by the immoral behaviors of their parents — but to his credit, he was the one whose work put the condition on the map, and got it recognized as its own unique disorder.

Meanwhile, according to Tourette Canada, Tourette was also making significant contributions in the study of hypnotism. He even hypothesized that a hypnotized person was incapable of committing crimes, though this concept was shattered when one of Tourette's own hypnotized patients shot him in the neck. After this disaster, Tourette's good reputation did a swan dive, and years later he ended up developing dementia and was placed in a psychiatric hospital.

Daniel Salmon didn't have to do much work for salmonella

Salmonella is named after a real salmon named Lucky (pictured above), who one day escaped from his tank and...

Just kidding. Salmonella is actually named after Daniel Salmon, the legendary animal doctor who earned a spot in the history books as the United States' first doctor of veterinary medicine. As if it weren't already impressive enough that such a notable veterinarian had the same name as a species of fish, AVMA points out that Dr. Salmon also headed up the Department of Agriculture's new Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI), and in less than eight years was able to stop the spread of a deadly contagion that had been spreading through Texas cattle. Salmon was also a huge proponent of the germ theory of disease. You know, back when germ theory was a big debate. Scary thought, right?

Anyway, Salmon's reputation was so lofty that a disease got named after him, even though he wasn't the one who found it. As the USDA points out, the actual credit goes to fellow BAI scientist Dr. Theobald Smith, who uncovered salmonella during a study of hog cholera. Though Smith probably deserves more credit, salmonella is a much more memorable name than "Smith's disease" would've been.

Baron Münchausen probably wouldn't be too happy today

Sometimes, all you want to do is have some drinks and tell a few good party stories. Maybe the drinks are really good, and maybe you exaggerate a little bit, but you certainly never expect that your tall tales will get you branded as a liar for centuries, much less have an entire psychological disorder named after you. However, these days, when a patient presents severe delusions about their health, perhaps even hurting themselves to make others "realize" how sick they are, it's generally referred to as Münchausen syndrome, though the Mayo Clinic might prefer it be called "factitious disorder."

Don't blame any of this on the real Münchausen, though. A German soldier who served for Russia in the 1700s, Britannica says after Münchausen retired, he gained a reputation for entertaining his guests with crazy good yarns about his military adventures. The real person became a fictional character in 1785, when writer Rudolf Erich Raspe published an account of wild imaginary stories credited to Münchausen, inspiring other storytellers to use a fictional Münchausen in their works as well. Suddenly, Münchausen was being portrayed as a bombastic con man, infamous for ridiculously exaggerated tales of bravery and adventure. The final whammy hit in the 1950s, when Dr. Richard Asher started describing patients with factitious disorder as having Münchausen syndrome.

Not matter how you slice it, Münchausen's ghost probably ain't thrilled about all this.

Why Reiter's syndrome isn't called Reiter's syndrome anymore

There's a certain type of arthritis that used to be called Reiter's syndrome, but pretty much everyone agrees this name should be kicked to the curb. Some have even mounted petitions to have the term scrubbed from all medical journals and discourse, and have successfully renamed it "reactive arthritis." Sadly, according to Scientific American, many doctors and patients have continued using the old name out of habit, perhaps not realizing its sinister history.

What's the big deal? You guessed it: Nazis.

Doctor Hans Conrad Julius Reiter was a Nazi doctor who conducted immoral human experimentation on concentration camp prisoners, slaughtering thousands of people in disturbing and inhuman ways. As if this wasn't reason enough to ditch his name, Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism points out that the first diagnosis of reactive arthritis also predated Reiter's research, so using his name for the diagnosis both makes no sense and honors a sadistic war criminal.

Klinefelter's mentor did him a solid

Maybe you've heard of Klinefelter syndrome, and maybe you haven't, but either way, it's a story of X's and Y's. According to Lynn Loriaux's A Biographical History of Endocrinology, Harry Klinefelter was working at Mass General studying under his hero, the noted clinical endocrinologist Fuller Albright. During one morning session, Klinefelter asked his mentor about a male patient who had both enlarged breasts and shrunken testicles. The two men decided to investigate, analyzing eight patients over a year. When they published the results, Albright allowed the younger doctor to snag the credit. Nice gesture, Doc.

Klinefelter syndrome, as the condition is now known, has to do with chromosomes. As the National Library of Medicine explains, men with this condition have an extra X chromosome (XXY instead of XY) and produce less testosterone than XY men, have less facial hair, are usually taller, and so on. Klinefelter's is more common than you probably realize, and there are some (unproven) claims that George Washington may even have had it.

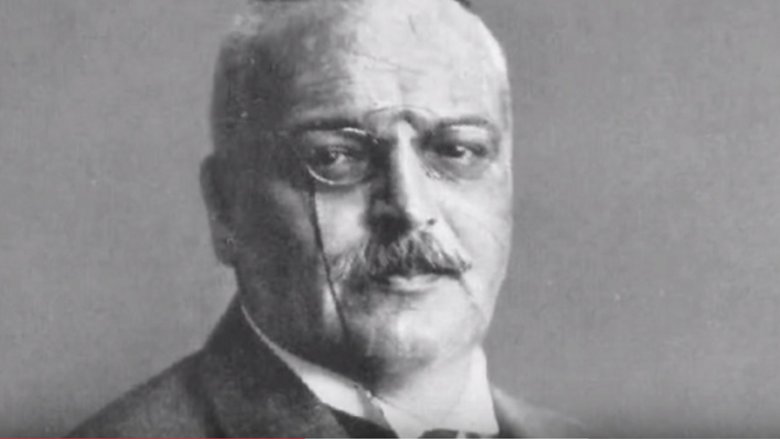

The cigar-chomping German psychiatrist who discovered Alzheimer's

If the life of Dr. Alois Alzheimer were turned into a movie today, it'd be an epic tragedy starring Harrison Ford and a German accent. Quirky, brilliant, and devoted to science, Alzheimer was remembered by his students as the kind of guy who puffed on his trademark cigar even when he was bent over a microscope. After the heartbreaking loss of his wife, Biography says Alzheimer plunged himself into the study of a 51-year-old woman named August Deter, who suffered from weird psychological ailments: memory loss, hallucinations, you know the drill. When Deter died in 1906, Alzheimer autopsied her brain, and first identified those terrifying plaques and tangles that people with elderly relatives know all too well today. According to Alzheimer's Disease International, the methods Alzheimer used to diagnosis Deter were so sophisticated that the disease is still diagnosed much the same way today, over a century later. And these days Alzheimer's disease is everywhere: The Alzheimer's Association estimates that it hits one of every three seniors.

Though Alois Alzheimer was celebrated for his work, his story eventually spiraled back into tragedy. According to neurologist Gayatri Devi, Alzheimer died from a severe cold when he was only 51 years old — the same age his patient August Deter had been when they'd first met. His daughter was only a teenager at this time, and his son Hans would later be hounded by the Nazis because of his Jewish background.

James Parkinson, a political rebel accused of trying to kill a king

The trembling, emotion-disrupting, dementia-caused nervous system disorder known as Parkinson's disease gets its name from Dr. James Parkinson, a 19th-century British physician who referred to his discovery as a "shaking palsy," according to the Scientific Electronic Library Online. Parkinson published his studies on the medical condition in 1816, based on examining six individuals with whom he deeply empathized, and hoped to one day cure.

Though Parkinson's contributions to science and medicine were huge, back in his day, people were more familiar with his radical political opinions. Parkinson was an outspoken advocate for pacifism, suffrage, and social reform, and believed the British parliament needed a kick in the pants. Parkinson's edgy reputation as a member of the London Corresponding Society gained him enough notoriety that when the British government uncovered an alleged plot to assassinate King George III, Parkinson was questioned and accused of having been involved in the conspiracy ... you know, even though he'd been busy preaching the values of pacifism. In the end, he was declared innocent, but it seems the ordeal was stressful enough that he spent the rest of his life focusing more on science.

Hans Asperger sent kids to be euthanized

Doctors don't (usually) say "Aspergers" anymore. These days the term has been swallowed up under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorder. Generally, the tale of Hans Asperger — the Austrian doctor who first identified "autism" — is presented as a heroic fable, with Asperger himself claiming to have advocated for disabled children and even saved their lives. However, in an interview with Vox, historian Edith Sheffer revealed a shocking truth: the acclaimed doctor also sent kids to be experimented on and euthanized by the Nazis.

Asperger himself wasn't in the Nazi party, and it's possible that he may indeed have rescued children from the Third Reich, as he claimed. However, none of that forgives the fact that he sent dozens of children to Nazi killing centers, and his association with the euthanasia program was not mandatory: He did it by choice and had no problem hanging out with other scientists who were busy experimenting on live humans.

While Asperger's is no longer a medical diagnosis today, some in the community have worn the label with pride. In light of these disturbing revelations about Hans Asperger, Sheffer — whose son is diagnosed on the autism spectrum — recommends the decision on whether to keep the name Asperger's should be decided by the community itself, and not by others.

Hakaru Hashimoto made a big discovery, then disappeared

An unusual swelling of your thyroid gland is called a goiter, and the usual cause is a lack of iodine. However, a particular type of goiter which isn't caused by iodine deficiency is called Hashimoto's disease, according to the Endocrine Journal, and takes its name from a humble, mysterious Japanese surgeon named Hakaru Hashimoto. Born in a small village and coming from a line of physicians, according to Dr. Clark Sawin, Hashimoto was a third-born son whose two older brothers were dead before he touched the ground. Growing to become a surgeon, Hashimoto needed a topic for his M.D. thesis. He chose goiters, and eventually discovered the abnormal ones that are now named after him. Hashimoto published his results in a German magazine, writing his work in the German language, hoping it might gain more attention that way.

Unfortunately, the acclaim that Hashimoto deserved did not come to him until after his death. After publishing this paper, Hashimoto returned to his home village and spent the remainder of his years living a quiet existence as a local physician. Little is known about his life, but he died at age 52 from a bout with typhoid.

Before ice buckets, there was baseball

Remember that whole ice bucket challenge thing, where everyone from your next door neighbor to George W. Bush got freezing water dumped on them? Well, that was a viral charity event to raise money for ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) research, a neurodegenerative medical condition most people know as Lou Gehrig's disease, named after a certain famous New York Yankees player.

According to the Texas ALS Association, the disease was first diagnosed in 1869 by Jean Martin Charcot, but it didn't gain mainstream attention until 1939, when Gehrig revealed his diagnosis to the world. Previously, Gehrig had been known as the "iron man" of baseball, a man in his prime, and his rapid decline shocked the nation: He died only two years later, and according to Biography, by the end of his life he'd become too frail to even sign his own name. Gehrig certainly didn't rename ALS after himself, nor did anyone else, but the nickname became a popular tribute to the bravery he showed in opening up about this disease the world, giving it a level of mainstream attention it never had before. However, it has recently emerged that Lou Gehrig may not even have had ALS.