The Weirdest Ways Illnesses Changed History

Diseases can change your life in the darnedest ways. For example, let's say you have crabs but only find out after infecting your boss' spouse. Suddenly, your affair feels like a mistake. Your boss' spouse abandons you like a sinking ship and vengefully rats you out. You get fired and can't find another job because you keep scratching your horrifically itchy no-no zone during interviews. Before long, you lose your home and start living in a trash can. You grow increasingly crabby and scream "scram!" at anyone who offers help. You die alone covered in furry green fungus you contracted from your trash can.

If hypothetical love lice can turn you into a gritty Oscar the Grouch, just imagine how actual illnesses impacted people and events across history. Maybe the flu influenced major legislation or inflamed bowels ignited a political movement. Perhaps one of your ancestors gave crabs to a butterfly, triggering a chain reaction that made the future itchier. Will some of the things you do or say today be bizarrely connected to deadly diarrhea? Here are the weirdest ways illnesses have influenced history.

The royal flush that saved the Magna Carta

King John was essentially a royal toilet. (Even his name means "toilet.") The 13-century English monarch treated friends and foes like crap, per The Telegraph. He imprisoned subjects to take their land, starved enemies to death, defiled the wives and daughters of nobles, and murdered his nephew. He also plunged England into war, only to run from battle and leave allies in a lurch. As one academic smartly put it, John was "a sh*t," which is fitting since the despised despot pooped himself to death.

In 1216 John died of dysentery, which the BBC described as "diarrhea so violent it causes bleeding and death." The fatal rump eruption didn't just end his life; it revived the recently killed Magna Carta. John signed the document in 1215 after his barons rebelled and besieged London. If implemented, the game-changing charter would have reined in the king, prohibiting arbitrary imprisonment, exile, and property appropriation. It even laid the foundations for England's parliament, according to the British Library. But John had zero desire to honor the Magna Carta.

John only put his Self Hancock on the document because he wanted to stall until the weather got too bad for battle. Intent on torpedoing the Magna Carta, he sent a copy to the pope, who pronounced it invalid. But once John skipped to the loo in the sky, his 9-year-old son became king. Adults later redrafted the document, and the liberties it promised eventually became reified.

No guts, no glory: a tale of dire rears

Dysentery didn't single out King John. It waged war on everyone, especially soldiers. In 1900 the Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin noted that the bacterial baddie was reportedly "more fatal to armies than powder and shot." Per History, dysentery decimated at least a third of British troops before the Battle of Agincourt –- one of Britain's most celebrated military triumphs. Archers allegedly had to cut off their underpants to "allow nature to take its course" during combat.

Besides making war more offensive, diarrhea-related ailments like dysentery played a crucial role in crucial conflicts. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics named soupy pooping as a deciding factor in the Crimean, Napoleonic, and Franco-Prussian wars, among others. A sickly brown wave may have also turned the tide of the U.S. Civil War. Montana State University explained that Confederate General Robert E. Lee basically became a fountain of feces during the Battle of Gettysburg, prompting Civil War buffs to speculate that diarrhea aided in his defeat.

Regardless of whether the runs ruined Lee, they left a distinctive mark on America. More than 1.7 million Union soldiers had dysentery or diarrhea during the Civil War and countless Confederates also suffered. Battlefield etiquette forbade shooting soldiers while they explosively pooped. From that ethos emerged the saying, "no guts, no glory." Having "the guts to fight" didn't denote bravery, but rather the absence of diarrhea. If Quentin Tarantino made a Civil War flick, he'd practically have to call it Inglourious Base Turds.

The stroke that turned the White House into the wife's house

Woodrow Wilson had a great mind and a troubled brain. Before becoming president in 1912 the former Princeton professor had already suffered two strokes. As the University of Arizona detailed, the incidents impaired his right hand and left eye. A third stroke during his first term harmed his left arm. Despite doctors' worries, Wilson consistently dismissed his condition. After all, if three strokes couldn't crack his egghead, what could?

A fourth stroke, unfortunately. It was 1919. Wilson had endured disability and the passing of his first wife from kidney disease. He had recovered, remarried, and gotten reelected. But he had no recourse when a severe blood flow blockage ambushed his brain. Per PBS, the stroke paralyzed his left side and blinded his right eye. Wilson's second wife, Edith, masterminded a cover-up. She hid his immobility with a blanket and secretly began managing White House matters.

Though she later denied making official decisions, Edith decided which government documents her husband handled. She also handled officials she deemed disrespectful. According to the National First Ladies Library, when the Secretary of State convened Cabinet meetings without the president, Edith got him fired. Additionally, she rejected the credentials of a British ambassador sent to help promote the League of Nations to Congress. The ambassador's aide had jokingly demeaned Edith, who wasn't amused. Per the book Madam President, she further wielded power by blocking attempts to negotiate the League of Nations, possibly prompting Congress to reject it.

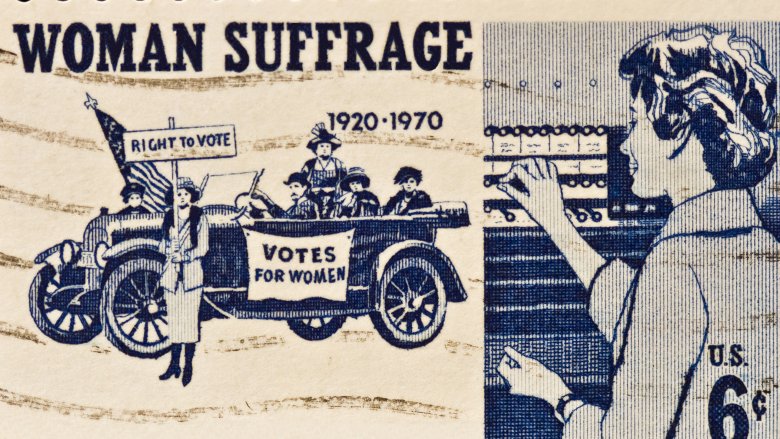

Influenza sufferers and influential suffragettes

Edith Wilson made history, but she also made less sense than a confused penny. As author William Hazelgrove noted, the woman who ran the White House couldn't stand suffragettes. Ironically, one of the reasons she found herself in charge was that pro-suffrage states supported Woodrow Wilson's reelection. In fact, he advocated giving women the right to vote in 1917, whereas Edith advocated keeping them incarcerated for their protests. Maybe the most glaring incongruity was that while Edith reviled the Suffrage Movement, she became empowered the way many suffragettes did: by assuming the duties of a man hampered by poor health.

In 1917 America entered World War I. The next year a worldwide scourge entered America. The 1918 flu pandemic obliterated populations across the planet. As the National Archives described, it infected one-fifth of the world's people. A quarter of Americans caught it, reducing the country's average life expectancy by 12 years. It hit men the hardest. According to The Conversation, the flu killed more U.S. soldiers than combat did. The physical closeness required by conflict helped the virus replicate rapidly.

As men dropped like bombs, women rose to the occasion. They filled the manufacturing void left by men. They found employment in fields where they were previously forbidden, such as textiles. And "by 1920 women made up 21 percent of all gainfully employed individuals in the country." Given their obvious capabilities, it was obviously absurd to stop them from voting.

The sickening reason vampires used to suck

Nowadays, vampires are like Viagra –- they keep you up at night by being exciting. They're not sadistic monsters but seductive mosquitoes that puncture and pleasure you simultaneously in fantasies. Long ago, though, they sucked in undesirable ways. People sincerely feared vampires and fervently sought to stop them. So what changed?

Centuries ago, vampires weren't entertainment; they were explanations. Germ theory didn't emerge until the 19th century. (Even then, information traveled like a sluggish snail.) Before that, people didn't comprehend why communicable diseases spread or how cadavers decayed. It was a recipe for rampant superstitions. As National Geographic elaborated, corpse skin shrivels, producing the illusion that the teeth and nails grew. Meanwhile, fluids ooze from orifices, creating the appearance of bleeding. These processes appeared unnatural, so people called them supernatural. When deadly epidemics like the plague or tuberculosis created an abundance of bodies, people assumed the undead were feasting on the not-dead.

These proto-vampires had various monikers. Sixteenth-century Italians dubbed them "strega," which referred to either vampires or witches. Seventeenth-century Germans called them "Nachzehrer," or "after-devourers." Others knew them as "aaaahhh!" Fearful denizens defended themselves in inventive ways, like lodging rocks in a corpse's kisser or burning its heart and feeding the ashes to a sick person. These misguided ideas made their way across Europe and across the ocean to America. According to The Atlantic, during the late 1800s, Eastern European vampire myths reached Irish author Bram Stoker, the mind behind everyone's favorite bloodsucker, Dracula.

Leprosy: the darker shade of pale

Economist Adam Smith saw science as "the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition." Unfortunately, not every scientist of antiquity had Smith's eyes. Some wrapped superstition in stilted language and enthusiastically called it science. Take, for example, the theory that black people were Caucasians with leprosy.

The idea stemmed from attempts to explain racial distinctions and excuse racial discrimination. As author David Whitford detailed, when the transatlantic slave trade took off during the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans blamed the Bible for black enslavement. In Genesis Noah (of Ark fame) cursed the descendants of his son Ham to become slaves. Clearly taking a leap of faith, slavers decided those descendants were black. Americans inherited that narrative, but as PBS pointed out, during the 1800s they sought "scientific" reasons for racial differences.

Enter Benjamin Rush, the father of American psychiatry. Per the book Body Matters, Rush believed blacks suffered from a lesser form of leprosy called "negritude." Interestingly, people also used to see leprosy as a divine curse. But with Rush's help, it graduated from superstition to pseudoscience. The physician asserted that negritude caused dark skin, big lips, "strong venereal desires," and insensitivity to hot coals. As evidence, Rush referenced a black man who seemingly became white and argued negritude could be cured. Really, that guy had vitiligo, which turns dark skin light. To Rush's credit, he opposed slavery. However, he also opposed interracial marriage since mixed children might inherit negritude.

Tanning: the bright side of tuberculosis

Unless your name is Doc Holliday and you live in the movie Tombstone, there's nothing charming about tuberculosis. And if you are Doc, you still end up with a tombstone. At best, it's a wash. At worst, you cough to death. Then again, if you lived in Victorian England, it didn't take a gunslinger firing zingers to make violent respiratory failure look cool.

Victorians called tuberculosis consumption, and it absolutely consumed them. Professor Carolyn Day told Smithsonian Magazine that "between 1780 and 1850" the consumption symptoms became "entwined with feminine beauty." The disease caused appallingly pale skin and skeletal thinness. It was basically heroin chic for old-timey Brits. Of course, ignorance contributed to that bliss. Much like tuberculosis, miasma theory was fashionable at the time. Many people thought "bad air" transmitted tuberculosis. Others attributed it to bad genes. Granted, neither perspective really explains why resembling sweaty snow became so popular.

For a while people tried look like tuberculosis sufferers. But in the late 19th century, germ theory blew bad air out of the water. In 1882 Robert Koch uncovered the bacteria responsible for consumption. Soon doctors began discouraging long dresses, beards, and anything else they thought trapped germs. A huge shift occurred in the 1920s and '30s when physicians started prescribing sunlight to fight tuberculosis and rickets. Per the American Public Health Association, people increasingly viewed tans as attractive. Partly thanks to consumption, consumers now cough up money at salons to roast themselves.

Consumption junction with construction

When researchers realized consumption came from combatable pathogens, doctors declared war. Fortunately, for physicians, war is health, so instead of designing tiny bullets, they built large facilities known as sanitariums. According to Medical History, the structures contained terraces, balconies, big windows, flat roofs, and sunrooms. Armed with the knowledge that sunlight lessened tuberculosis symptoms, doctors were literally trying to brighten their patients' days.

This health-centered mindset shaped the modernist movement, which emerged at the tail end of the 1800s. Architects imbued buildings with swanky sterility, intentionally replicating the features of sanitariums. Modernist dwellings boasted balconies and bigger windows. Flats had flat roofs. Homes became whiter. These designs became especially prevalent after World War I, when much of Europe got shot to shambles. Germany birthed the Bauhaus school, "arguably the most influential architecture, art and design school of the 20th century," according to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Bauhaus was built on modernist principles. Founder Walter Gropius combined austere industrialism with the hygienic aesthetic. Homes were specifically designed with influenza and tuberculosis in mind. When Hitler ascended to power in 1933, he banned the Bauhaus, per the BBC. As a result, Walter Gropius went to the U.S. and took American architecture by storm. Apple founder Steve Jobs loved the Bauhaus look. As Smithsonian Magazine noted, in 1983 Jobs championed "Bauhaus simplicity" as the future of product design. He then proceeded to fulfill his own prophecy.

Tuberculosis: George's Orwellian nightmare

Before 1984, which George Orwell finished writing in 1948, a "big brother" was someone who broke your toys and farted on you in your sleep. Afterward, people tied those words to Big Brother, a dystopian dictator who steals your freedom and takes a dysentery-worthy dump on your dreams. When someone wants to skewer socialism, you can bet your last red cent they'll fill their two minutes of hate with 1984 references.

It's only appropriate that the book that coined the term "newspeak" created a new way of speaking about politics and propaganda. But according to infectious disease expert John Ross, Orwell's depressing tale about a suffocating surveillance state also reflected the depressing state of his suffocating lungs. The author struggled with bronchitis and tuberculosis (as well as infertility). In fact, while writing 1984, Orwell was withering under the strain of tuberculosis. Tellingly, the book's protagonist Winston Smith is a shrunken husk of his younger self. In Orwell's words, "The truly frightening thing was the emaciation of his body," which suggested Smith "[suffered] from some malignant disease."

Orwell directly attributed 1984's dismalness to his abysmal health. The Guardian's Robert McCrum observed that the author felt "ghastly most of the time." Orwell underwent grueling treatments that he likened to "sinking the ship to get rid of the rats." Coincidentally, Winston Smith's worst fear is rats, which are used to torture him.

The brain illness that birthed a tragedy

The pen may be mightier than the sword, but the hand holds both and is itself beholden to the brain. A mighty brain has the upper hand, but when brainpower fades, things get out of hand. Philosophical colossus Friedrich Nietzsche tragically illustrated that point in 1889. By that point he had authored 11 books, per The New Yorker, including The Birth of Tragedy and Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In that pivotal text he discussed the concept of the Overman, who overcomes the constraints of common morality. Unfortunately for Nietzsche, he couldn't overcome his own mortality.

At 44 years old, an enfeebled Nietzsche lost his mind. Critics would claim he succumbed to syphilis contracted from a prostitute. However, in 2003 physician Leonard Sax disputed that account, arguing that the philosopher's symptoms signaled an illness more like brain cancer. Whatever the case, Nietzsche ended up in the hands of his sister, Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Thus began a historical tragedy. Nietzsche expert Christian Niemeyer explained that Förster-Nietzsche hated Jews and unsuccessfully attempted to found an "Aryan" paradise in Paraguay. Nietzsche, however, detested anti-Semites and suggested ejecting them from Germany in his book Beyond Good and Evil.

Too bad Nietzsche's sister was beyond evil. Once her brother was powerless, Förster-Nietzsche imposed her will. She added anti-Semitic sentences to his writings, rearranged words, and forged letters. Hitler wielded her poisonous pen like a sword. The Nazis used Nietzsche's Overman as a symbol for Aryan supremacism. Nietzsche's eventual vindication, however, was a triumph of the ill.