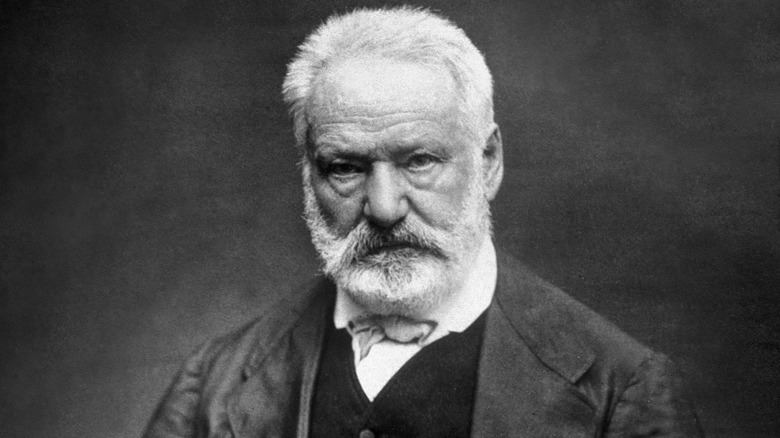

Why Does The Vietnamese Religion Cao Dai Revere Victor Hugo?

Even if you can't name one of 19th-century French writer Victor Hugo's works off the top of your head, you've definitely heard of them. Perhaps 1831's "Notre-Dame de Paris" rings a bell, at least in animated form in Disney's 1996 "The Hunchback of Notre Dame." Maybe you've watched or listened to "Les Misérables," one of the most beloved and well-known musicals in history, modeled after Hugo's 1862 epic novel. Or if you're amongst the literati, you might be more familiar with 1856's "Les Contemplations," a song-and-poetry collection that Hugo wrote in honor of his daughter Léopoldine and her husband, both of whom died in an accidental drowning in 1843.

No matter how you cut it, Hugo was one of the 1800s most well-respected writers, French language or otherwise. When he died in 1885, over 2 million people attended his funeral in Paris. Through his work he advocated kindness and respect for the working class, marginalized, and the poor, as International Socialist Review discusses. Some have been skeptical of Hugo's humanitarian authenticity, as The Atlantic describes, but many more hail him "the greatest poet of this century" and "the spiritual sovereign of the 19th century."

That last quote foretold Hugo's rise to revered status in Vietnam, which from 1858 fell under French colonial dominance. As LitHub describes, Hugo's compassionate sociopolitical views, combined with records of séances he held to contact his deceased daughter Léopoldine, made him a pillar of Cao Dai, a Vietnamese unitarian religion.

Séances in exile

Victor Hugo's place in Cao Dai began with his disgust of Napoleon III, emperor of France from 1852 to 1870 and nephew of history's famed Napoleon I, aka Napoleon Bonaparte. In a time of burgeoning French imperialism — and what Hugo saw as Napoleon III's unjust treatment of the poor — Hugo dubbed Napoleon III a "traitor" and was promptly exiled from his home country, as ThoughtCo. says. The New York Times tells us that Hugo fled to Belgium, then the island of Jersey off the French coast, then finally the nearby island of Guernsey in 1855. "Exile," Hugo said, "has not only detached me from France, it has almost detached me from the Earth."

Hugo started getting involved in séances on Jersey in 1853. In an attempt to cope with his daughter Léopoldine's death and also alleviate some of his island-bound boredom, Hugo tried contacting his daughter's spirit. He also tried contacting the spirits of historical people like Hannibal, Galileo, and Shakespeare. But most importantly, he didn't just conduct séances — he wrote his experiences down.

At one point Hugo was certain that he'd made contact with death itself, who commanded him to wait to publish his séance transcriptions until after his death. Specifically, Hugo was to posthumously publish the transcriptions in dribs and drabs once every 10 years. This is how Hugo's transcriptions outlived him and influenced Vietnamese people halfway across the world around 1925.

Fanning a Vietnamese revolution

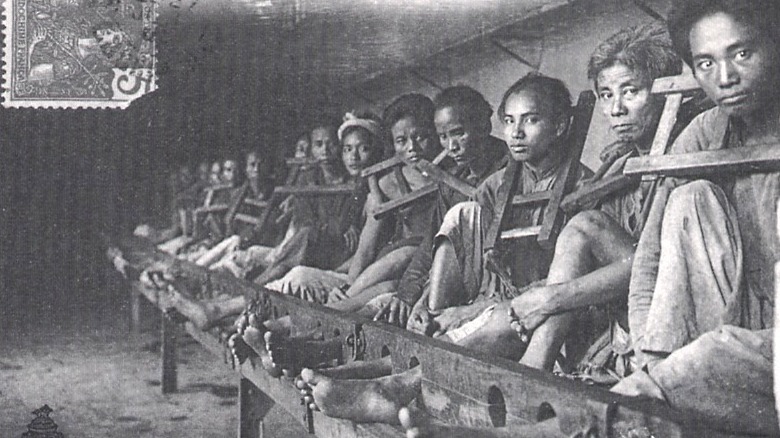

France pushed hard into what it called "Indochine Français" — French Indochina — during the reign of Napoleon III and his successors. Starting with Saigon in 1861 (modern-day Ho Chi Minh City), French occupation pushed through Vietnam and spilled over into its neighbors Laos and Cambodia. By the late 1880s, the French dominated the region and squeezed it for resources to funnel back through the French colonial empire. Vietnamese people were forcibly relocated to plantations to endure back-breaking, 15-hour days without food or water in squalor and slavery to generate rice, rubber, coal, tin, zinc, and more under threat of corporal punishment. One company, the still-recognizable tire manufacturer Michelin, recorded 17,000 worker deaths in 20 years.

While some Vietnamese people actively collaborated with their oppressors and rose to positions of governmental power — and were therefore regarded "nguoi phan quoc" (traitor) by their countrymen — most Vietnamese remained disdainful of the French and quietly furious. The French phased out local Confucian religious beliefs and implemented a Western-style education that extolled French culture and, most critically, used Roman letters to write the Vietnamese language. Temples, pagodas, and monuments were torn down, and street names, buildings, districts, etc., were given French names. All of this exposure to the French language had the ironic and inadvertent effect of opening up the Vietnamese population to the writings of the French intelligentsia, including the works of Victor Hugo.

The rising pillars of faith

Victor Hugo used his time in exile to not only conduct séances but also smuggle antigovernment, anti-Napoleon III treatises through French territory using sardine tins, bales of hay, and even busts of the emperor himself. Some of his work made its way to Vietnam and into the hands of French-reading and -speaking Vietnamese people, particularly those in positions of government. Hugo's humanitarianism and political dissent embodied the oft-cited French virtues of liberté, égalité, and fraternité (liberty, equality, and fraternity) and revealed the hypocritical cruelty of colonized life. Hugo became a kind of luminary of compassion and justice in Vietnamese circles even before his séance transcriptions arrived in Vietnam in 1925.

That same year in 1925, three Vietnamese government employees — Cao Quynh Cu, Pham Cong Tac, and Cao Hoai Sang — began conducting their own séances in secret and practiced a kind of East-West blended spiritism. They purported to make contact with an entity that called itself AAA, and Cao Dai (literally, "roofless tower"), the supreme being of the cosmos. Several years prior, Ngo Van Chieu, governor of the island of Phu Quoc off of Siam (modern-day Thailand), supposedly received a vision from that same being — Cao Dai — who told him that all the world's disparate religions needed to return to their single, unified origin. These key individuals, plus several others, officially and publicly founded the religion of Cao Dai in 1926.

The presence of Hugo's spirit

The arrival of Victor Hugo's séance transcriptions in Vietnam coincided perfectly with the rise of Cao Dai as both an inspirational tool and part of actual religious practice. Hugo had died decades earlier in 1885, but his spirit lived on to oversee the unfolding of Cao Dai's early days into its current, 5-million-member-strong worldwide religion — figuratively and literally.

Cao Dai was full of séances in its initial years, and its adherents claim to have contacted Victor Hugo's spirit. "Hugo became a comforting presence and regular at séances," LitHub says, "dictating poems and prayers for transcription, offering encouragement to fight against imperialist rule, and reiterating his prophecy that the next great world religion was on the horizon." At the cusp of West and East philosophy in a subjugated society stripped of its inherent Confucian roots, "Hugo's spirit surfaced out of natural affinity" as a renowned, prolific writer who wrote about fairness, social harmony, and was a spiritualist himself. Hugo's spirit appeared so often that by 1931 two Cao Dai members were dubbed Hugo's "spiritual children."

Meanwhile, Cao Dai Overseas says that the French-controlled Vietnamese government didn't take kindly to the rise of what it saw as a subversive ideology. Cao Dai, however, flourished decade-by-decade in underground circles and aboveground meetings. It outlasted French dominance of Vietnam, subsequent repression under the Ho Chi Minh-led communist revolution, a later Catholic government, and grew all the way to the present.

Figures of faith

The teachings of Cao Dai are exactly what you'd expect of a unitarian faith and can be described in terms of a few generalities on Cao Dai Overseas: everyone is a part of the same cosmic oneness, prayer and meditation puts people on the path to awareness, all religious teachings boil down to love and justice and have the same origin and purpose, and so on. Exo Travel also says that practitioners of Cao Dai are strict vegetarians, try to be kind to animals and other people, try to limit their use of curse words and alcohol, and believe in reincarnation. Cao Dai also reveres figures from faiths all around the world, including obvious names like Jesus, Mohammed, the Buddha, and Confucius, and less obvious choices that connect more to humanity's ongoing fight for civil freedom, like Joan of Arc or the Greek statesman Pericles. And yes, this includes Victor Hugo.

Victor Hugo had reached such a renowned status within Cao Dai by 1949 during the First Indochina War — when Ho Chi Minh rallied Vietnam to expel the French — that he was deemed the reincarnation of the 18th-century Vietnamese poet Nguyen Du. Since 1975, Cao Dai has no longer conducted séances as part of its practices, but Hugo remains a revered figure. Visitors to Cao Dai's main global temple in the city of Tây Ninh, Vietnam can even spot images of the French writer on the wall, continuing to inspire practitioners and travelers alike.