Drag Shows Are Older Than You Realize. Here's The Real History

Drag may seem to be everywhere right now, from reality TV to legislation that represents thinly-veiled attempts to restrict drag performances. Yet, despite what politicians or other pearl-clutchers may have you believe, this art form has been around for far longer than "RuPaul's Drag Race" or your local drag queen storytime. In fact, the history of drag performances goes back thousands of years and spans a multitude of cultures.

Broadly defined, drag is a performance art distinct from other forms of gender expression or exploration. Performers are known as drag queens when they represent female characters, and drag kings when they play male ones. They typically exaggerate gender norms for comedic effect, such as a drag queen putting on elaborate, heavy makeup and sky-high heels. However, it's important to note that because drag is a performance art, and one with a deep and diverse history, it isn't strictly associated with someone's gender identity. For example, a non-binary or transgender person wearing clothes that affirm their identity is not in drag (though transgender drag queens and kings certainly do exist).

At practically the same time that drag performances were getting attention, many LGBTQ people questioned rules that gendered certain types of clothing, makeup, and mannerisms. Some gathered in private drag balls or gained fame as "female impersonators." Eventually, both drag and LGBTQ communities became associated with one another and entered mainstream consciousness. But how did we really get here? This is the real history of drag shows.

Drag has roots in ancient Greece

In much of ancient Greece, it was simply tough to be a woman. Though conditions varied from city-state to city-state, many women in this region of the Mediterranean found that they were little more than property, used to create and maintain the next generation without much regard for their rights or desires. Certainly, if a woman in a place like Athens wanted to act on a stage in front of a crowd, she was out of luck. For much of ancient Greek theater, women were banned from taking part in public performances.

Yet there were plenty of parts meant for female characters, meaning that male actors necessarily had to embody femininity — or what they thought femininity was — to play women. It's hard to get an on-the-ground look at how stage femininity played out in comparison to the real lives of women. However, Sue-Ellen Case, writing in Theatre Journal, argues that this surely led to a bevy of stereotypes about women that became part of the acting tradition. The use of masks for all actors likely made this early forerunner of drag all the easier, while reinforcing gender norms.

Was this drag? Not exactly, especially if you compare it to the modern concept of drag with its associations with the LGBTQ community. But it certainly shares similar elements, especially with the exaggerated performance of gender that occurred after an ancient man donned a female mask and hair, before striding onto the stage.

Japanese theater has a dedicated tradition of men dressing as women

Much of Japan was cut off from the outside world after its shogun leaders implemented the sakoku policy in the late 16th century, all but barring travel into or out of the country. Over the next couple of centuries, the nation's isolationist policies stood, then eased, then were smashed when U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry forced his way into Tokyo Bay in 1853.

But what does this have to do with drag? During the early decades of sakoku, women were part of the popular theater tradition known as Kabuki. In 1629, they were banned from the stage by moralists who worried that their dancing would corrupt audience members, despite a pre-existing tradition of all-women shows known as onna kabuki, per Britannica. This left theater companies with a bevy of female roles and no women to act in them. The solution: drag.

More specifically, the solution of men dressing and performing as women evolved into an acting niche now known as onnagata. For generations, it could be written off as a practical thing, but with the restoration of women to the Japanese stage in the late 19th century, the onnagata remained. These actors, with their stylized way of presenting themselves as feminine through dress, makeup, and even their physical stance, are still part of modern kabuki. Some performers, like Bandō Tamasaburō V, became undeniable superstars for their work as gender-bending onnagata.

Shakespeare played with the idea of drag

Much like in ancient Greece or Edo period Japan, hopeful actors in Shakespeare's England had better be male if they wanted to be on the right side of society. While there wasn't a law expressly forbidding women from public performances, it was seriously frowned upon and associated with all sorts of untoward behavior. More puritanical folks assumed that the theater in general was too bawdy for anyone to take part, much less women. But if there had to be theater, then the women might as well be played by men.

While actors playing Shakespearean characters engaged in cross-dressing, Shakespeare's take on gender and drag goes further than the practicalities of the stage. His plays also engage with the concept of gender, especially when audiences knew that the maiden on stage was played by a young man who might be exaggerating the look to get a point across. Take "Twelfth Night," a comedy that sees the main character Viola dress as a man, then woo both a woman and a man before her female identity is revealed and Elizabethan social norms are restored. The fact that the earliest performances of this play would have been put on by an all-male ensemble further complicates the already nebulous take on gender that Shakespeare presents in the script.

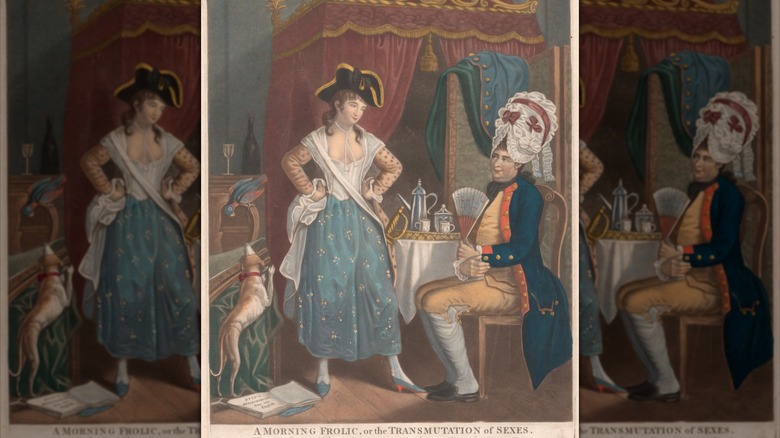

Princess Seraphina was a fixture of British molly houses

Being gay in 18th-century England was not exactly a recipe for a safe and comfortable life. Yet, despite the widespread disdain and even violence levied against them, queer people of this time and place still formed communities that offered both mutual support and good times. In fact, they might have seemed familiar to anyone who's attended a drag show in a modern gay bar, so long as you ignore the lack of electricity. Popularly known as "molly houses," these spots — which could be in private or public spaces — allowed queer men the opportunity to congregate.

Drag was very definitely part of this world. Attendees were often found clad in fine dresses and with full faces of feminine makeup. People in molly houses might even put on whole plays where participants pretended to give birth or marry each other.

Despite the regular raids and potentially deadly consequences (the death penalty for sodomy wasn't repealed in Britain until 1861, and the act was decriminalized in only 1967), we know of some named people of this world. One, popularly known as "Princess Seraphina," may even qualify as an early drag queen. Also known as manservant John Cooper, Seraphina was a regular fixture of the molly house scene, according to "Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England" (via Rictor Norton). Dressed in women's clothing, she often ran messages for other men. In 1732, she brought charges against another man for stealing her clothing, but appeared to face no consequences for her activities or dress.

The first self-termed drag queen was a Black American

When it comes to modern terminology, we don't hear much about drag queens until the late 19th century. The first known person to refer to themself as a "queen of drag" was William Dorsey Swann. Born in 1860 in Maryland, Swann was a former slave who became known for holding drag balls, despite the widespread homophobia and strict gender norms of the era, per The Nation. In 1888, police in Washington, D.C. raided one of these get-togethers and roughed up Swann, who was dressed in an evening gown. He reportedly told an officer: "You is no gentleman."

Police records of raids make it clear that drag balls had become a fixture of the gay scene by the late 19th century in D.C. While many attendees ran at the first sign of a raid, those unfortunates who were caught often had their identities published in local papers, subjecting them to ridicule and retribution. Yet Swann did not take the publicity of the 1887 raid as a sign to back down and continued facilitating drag balls.

Convicted of "keeping a disorderly house" in 1896, Swann wrote to President Grover Cleveland, arguing that he had done nothing wrong and deserved a pardon. No such clemency came his way. Swann eventually stepped back from his role as a drag queen and party organizer. His younger brother, Daniel, took on the mantle, hosting parties, crafting costumes, and becoming a fixture of the D.C. drag scene until his death in 1954.

Drag was part of the vaudeville circuit

During the heyday of vaudeville in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, drag found a new role. The comedic tone of vaudeville provided just enough cover for drag stars to make a living while mugging for laughs in the "wrong" clothes. Yet, some LGBTQ performers were forced to keep their sexuality and gender under wraps, as audiences only accepted drag under very particular conditions. The British Ernest Boulton — or Stella, as she preferred to be called — only found acceptance as a late 19th-century drag performer after leaving her homeland and keeping her sexuality quiet, according to the BBC.

Another performer, Julian Eltinge, was an especially popular drag performer in the 1900s. Where some performances hinged on the joke that the person on stage was a man, Eltinge rose to fame because his act as a singing and dancing high-class woman was considered very convincing, even for King Edward VII of England. While some may debate whether or not this quasi-sincere act counts as drag, Eltinge's rather glamorous and exaggerated take on femininity — with sweeping gowns, gobs of jewelry, and a full face of makeup — easily draws comparisons to modern drag shows. Though he made quite a bit of money and starred in films up to 1940, Eltinge felt that he had to present himself as extra-masculine offstage to counter his public image. Likewise, his private life was a closely-guarded secret, and no relationships between any gender person and Eltinge have come to light.

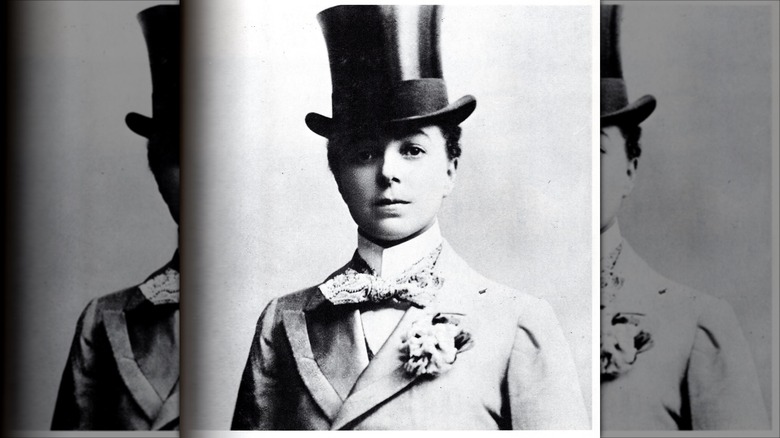

Drag kings have roots in nightclub acts

It just won't do to forget the kings — specifically, drag kings. As Dr. Jacob Bloomfield told History Extra, as women became more accepted on 17th-century European stages, they took over roles previously played by young boys. Eventually, some became specialists in male roles. The American Annie Hindle took to post-Civil War stages as a comedic male impersonator. Later, the British Vesta Tilley was so popular that she got an entire World War I platoon to sign up under her name. Yet, while some of these early male impersonators may have been LGBTQ, the fear of prosecution and social sanction pushed many to deny even a whiff of queerness or sexual impropriety.

That wasn't necessarily the case for some nightclub performers, who were sometimes bolder about taking on personas that can seem an awful lot like male drag. Gladys Bentley became notorious in 1930s New York City for performing sexually explicit songs while wearing a masculine ensemble that typically included a top hat, tails, and bow tie. She was promoted as a male impersonator, though it's clear that Bentley also preferred wearing masculine clothing and wasn't shy about her relationships with women. Towards the end of her career, however, Bentley claimed that doctors had "fixed" her and she was now happily wearing dresses and marrying men.

Drag parties became a big deal during Prohibition

As the United States entered into the purportedly alcohol-free era known as Prohibition, many party-loving Americans simply went underground. While national Prohibition lasted from 1920 until 1933, plenty of speakeasies sprung up to serve booze and host a good time. Many partygoers were also willing to push societal boundaries when it came to things like gender. And though gay bars and drag balls had already been around for many decades at this point, the growing underground nightclub scene led to what many later deemed the "Pansy Craze."

In short, during the Pansy Craze, quite a few underground LGBTQ night spots proliferated across America, with drag queens in residence at many of them. Yet many still found that the United States was too puritanical to let them live and work, as police commissioners began raiding night spots. Some drag queens found a safe haven in Europe, especially in the clubs of Berlin ... that is, until the fascist Nazis rose to power and began cracking down on anyone who didn't fit their narrow definition of what was socially acceptable. Still, though the 1930s saw the decline of the Pansy Craze on both sides of the Atlantic, it was clear that drag performers weren't going anywhere.

Drag balls sprung up in defiance of anti-cross-dressing laws

Throughout the history of drag shows, authorities were often found trying to shut them down. Many have hidden behind euphemisms and assumptions about how to perform gender. Consider the raids that led to the transformative 1969 Stonewall uprising and the modern gay rights movement. Patrons at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City's Greenwich Village, were subject to police raids that detained people who were found wearing too many pieces of clothing supposedly meant for another gender.

Transgender people and drag queens were both targeted by this particular policy, and the broader homophobic intent of the NYPD. But LGBTQ people were hardly ready to back down. Besides the riots that took place at Stonewall after a raid the night of June 28, 1969, drag queens reacted by further strengthening the drag ball community in New York and beyond.

Drag balls got their start in Harlem following the Civil War, but experienced a serious boost beginning in the 1970s, per History. This era saw the beginning of drag houses, a collective of queens headed and guided by a drag "mother." The first, the House of LaBieja, was formed after drag queen Crystal LaBieja spoke out against racist judging that left Black and Latinx queens behind in favor of white contestants. With the rise of the house system, drag balls developed hallmarks of drag culture that can be seen today, like the competitions on shows like the long-standing "RuPaul's Drag Race."

Drag hit the mainstream in the 1990s

Though plenty of people knew about drag performers, drag balls, and anything else associated with the art form for generations, drag still wasn't quite part of the wider cultural consciousness until the last decade of the 20th century. For many in the 1990s, their introduction to drag came courtesy of one person: RuPaul.

Of course, many drag queens have made waves before and after the rise of RuPaul Charles, but it's hard to deny his role in bringing drag to just about everyone's attention. RuPaul — who has stated that he doesn't prefer any particular set of pronouns — came out of Manhattan's thriving drag community of the 1980s and 1990s. His 1992 single, "Supermodel (You Better Work)," became a hit and landed him spots on nighttime talk shows, a contract with MAC Cosmetics, and a stint hosting "The RuPaul Show" on VH1. Other drag queens soon found that they were in wider demand, too. Though the following years saw a lull in interest, the 2009 debut of "RuPaul's Drag Race" on Logo underlined another resurgence in drag that continues to this day.

Modern drag was also given an NYC-based boost by a festival known as "Wigstock." What initially began as an impromptu 1984 performance in a park blossomed into a popular festival featuring a who's who of New York drag performers, including festival co-founder Lady Bunny, who helped oversee a 2018 revival of Wigstock with Neil Patrick Harris.

Drag shows have entered politics

You can reasonably argue that drag shows have always been political in one way or another — it's hard not to be when gender identity is literally policed, as during 20th-century raids of American gay bars. Moreover, drag has been part of political demonstrations for decades, such as the activism of the drag nuns of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, who first organized in 1979.

More recent years have seen politics and drag draw even closer together. Many drag queens are now public figures with large followings and considerable platforms. Moreover, given drag's close association with the LGBTQ community, legislation and actions that target queer people are often up for discussion in drag spaces. Popular drag conventions like DragCon can include presentations by civil liberties and voting organizations, while then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi appeared on season 7 of "RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars" in 2022.

Drag shows in particular have come to political attention because of recent legislation meant to restrict drag performances. In 2023, Tennessee state legislators passed a bill banning "adult cabaret" performances from public property, or any other venue that might host underage children. Per the language of the bill, these performers include "male or female impersonators." The vague language of the legislation has caused some to worry that it could be used to more fully restrict drag shows, or encourage the false assumption that LGBTQ people or drag performers would harm children, and has led to widespread political debate.