The Most Disastrous Coronations In History

The coronation is a dying ceremony. Per the BBC, the United Kingdom is the last monarchy in Europe to ritually place a crown upon a monarch's head, and only a handful of countries elsewhere still retain comparable rites. A coronation isn't necessary for a king or queen to become head of state — in most monarchies, that is accomplished automatically as soon as the previous sovereign vacates the throne — and there are simpler ways to mark their accession. Inaugural addresses and enthronements have become the norm for most crowned heads of state.

Once upon a time, coronations were seen as much more than an acknowledgment of a new monarch. What began as a simple wearing of a diadem became a deeply religious ceremony during the medieval period. The notion of divine right wasn't just a smokescreen for absolute power, but a true belief — at least for some rulers and their subjects — that monarchs were symbols of a higher power, signifiers of the unification of a people under God's grace and personally responsible for good and fair governance. The British coronation rite retains such dictates even as religiosity in Britain has declined, and the monarchy shed most of its powers.

Such a ceremony is intended to be a solemn and flawlessly executed endeavor. Being the work of humans, it has inevitably gone wrong sometimes. Coronation mistakes through the ages have ranged from mispronunciations of the liturgy to tragedies that left scores of royal subjects dead, and everything in between.

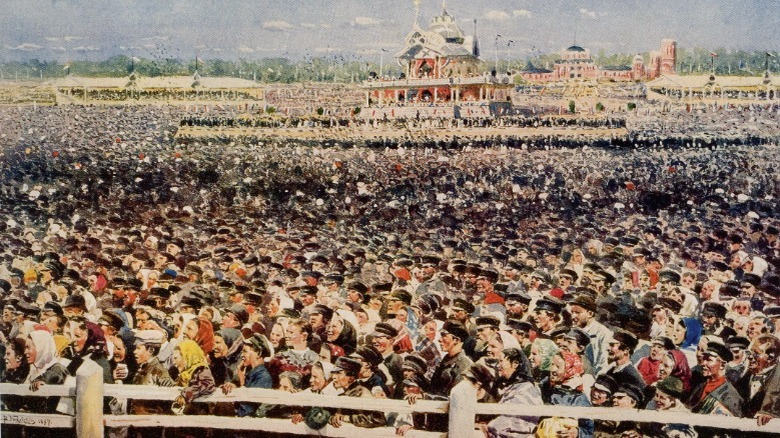

The Khodynka tragedy of Nicholas II

Very little went right for Nicholas II as tsar of Russia. He came to the throne at the age of 26 after the death of his father, Alexander III, who put little effort into preparing his son to rule. His choice of spouse, Alexandra, pleased neither his parents nor his country. And the events of his coronation put a black cloud over his reputation as tsar from the very beginning.

The ceremony itself, an elaborate five-hour affair in Moscow, went off almost without a hitch. The only slip-up seemed to be that a ceremonial chain fell off during the service (per Robert Massie's "Nicholas and Alexandra"). But outside the city, the traditional feast at Khodynka Meadow for ordinary Russians (pictured) went horribly wrong. Beer and gifts were to be given out at the feast, and a rumor began among the crowd of thousands that there wasn't enough to go around. A push to get to the gift booths, many of them poorly placed over the uneven terrain, turned into a crowd crush that left 1,282 dead and thousands more wounded.

Nicholas was horrified by the tragedy. He buried the dead and compensated the survivors at his own expense, spent the days after the coronation visiting the wounded, and wanted to spend the night of the tragedy praying. Pressure from his ministers meant that instead, the deeply unhappy tsar attended a ball thrown by the French ambassador, which led to many observers characterizing him as frivolous and uncaring.

George III's coronation was riddled with gaffes

Compared with the loss of the American colonies and his long struggles with physical and mental health, George III's coronation seem a minor hiccup in his reign at worst. But at the time, observers found it an embarrassing debacle. According to Roy Strong's "Coronation," one attendee wrote that it was a collection of "mistakes and stupidities."

As the first Hanoverian king of Britain born and raised in the country, George took pride in being British and took his duties seriously. He, at least, was well-prepared for his coronation, coming right on the heels of his marriage to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. But things outside the king's control started going wrong almost immediately, as carriages crashed in the race to Westminster Abbey on the day. The canopy over the royal heads was so poorly constructed that Queen Charlotte feared it would collapse on them. Wine was smuggled in by attendees, and they used it to wash down the food they appropriated while the Archbishop of Canterbury spoke. Heralds misspoke throughout the service, with the king himself gently offering corrections.

The congregation in the church still cheered at the sight of the new king in his crown, and the feast afterward. George III apparently found it a very amusing day. And care was taken to ensure that the next coronation would run more smoothly after all the "confusion, irregularity, and disorder," as James Henning put it (via "Coronation").

George IV locked his wife out of the coronation

George IV always liked the finer things in life. Hedonism took its toll; by the time he took the throne in 1820, after serving as regent for his ailing father for nine years, the 49-year-old king was extremely heavyset and unpopular for his spendthrift ways. Extravagance was evident at his coronation, done at a cost of £230,000 (over £32.3 million in 2023). But the great scandal of George IV's coronation wasn't the expense, or tawdry gossip over the king sweating through his finery, but the fact that his wife, the queen, was demanding entry outside the doors of Westminster Abbey.

Caroline of Brunswick was George's first cousin, and the two never liked one another. Their marriage was the price George had to pay to get Parliament to settle his enormous debts. Never mind that he was already married to Maria Fizherbert; she was a Catholic commoner, and George III's refusal to accept it meant the marriage was invalid in British legal eyes (per The Collector). Almost immediately after their only child was born, George and Caroline separated. Despite her popularity with the masses, Caroline was unwelcome at court and was at one point paid to go abroad.

George was working to divorce Caroline when he became king and had guards standing by to deny her entry into Westminster Abbey. That didn't stop her from trying four times, finally turning away when the abbey's door was literally slammed in her face. She died only months later.

Bokassa put a hole in his country's GDP to be crowned

Jean-Bedel Bokassa had already governed the Central African Republic (CAR) for 12 years before he was crowned. A veteran of World War II and a soldier in the French colonial army, he came to power in a coup d'état against his cousin in 1966. His past service with France kept him in good standing with that country's leaders, even as his own regime mixed major construction and mining projects with brutality and incompetence. According to Time, Bokassa allegedly boasted, "Everything here was financed by the French government. We ask the French for money, get it, and waste it."

Bokassa gradually inflated his title, from president in 1966 to marshal in 1974. He appropriated government funds for his own lavish lifestyle, consolidated cabinet positions in his own person, and seized control over key resources. By 1977, he had declared himself emperor and arranged for a lavish coronation, based on the one for Napoleon Bonaparte and priced at $20 million for a country with an annual GDP of $250 million (the French, among other foreign backers, helped cover the cost). New crowns and regalia were created (pictured), and expensive food, drink, clothes, and horses were flown in from abroad. Of Bokassa's 17 wives, he crowned one empress: a woman he'd kidnapped as a child.

The gaudy, over-the-top coronation was widely mocked in Africa outside the CAR, and the new regime only lasted two years. Bokassa's brutality finally proved too much for the French, who supported his overthrow while abroad.

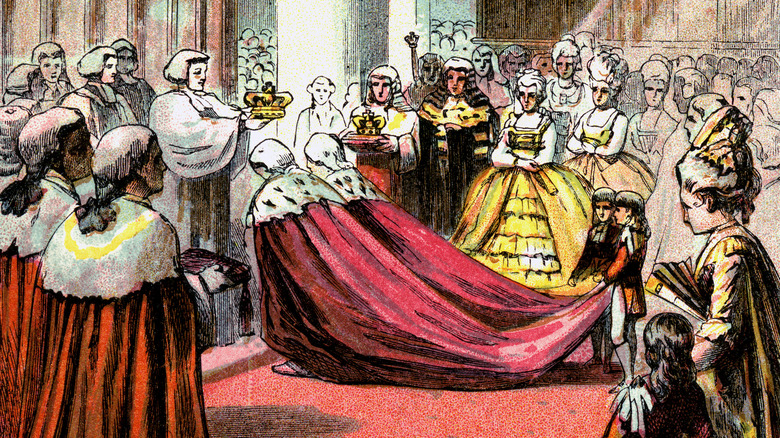

Queen Victoria's unrehearsed coronation

With Britain being the last holdout in Europe for practicing coronations, you might think that the ceremony has always been a well-oiled machine, working from ancient playbooks to deliver pomp and majesty every time a new king or queen sits St. Edward's Chair. But monarchs don't always appreciate the trappings of their authority. William IV, for example, was so hostile to ceremony of any sort that he would have scrapped the coronation if Parliament and the nation had let him. His frugal and stripped-down compromise dispensed with a number of long-standing traditions going back to the Middle Ages.

By the time William died and his niece, Victoria, took the throne, the state apparatus was unprepared for a more lavish coronation, which Parliament felt a young queen should have, according to Juliet Gardiner's "Queen Victoria." Victoria herself hadn't ever attended a coronation, and the year between her accession and the ceremony did nothing to ease her nerves. Per Roy Strong's "Coronation," rehearsal was minimal and unorganized.

When the day came, the lack of preparation showed. Pages of the liturgy were skipped, the sovereign's orb was given to Victoria too early, and the Archbishop of Canterbury rammed the coronation ring onto the wrong finger on her hand, which the queen recorded was extremely painful. The elderly Lord Rolle literally fell and rolled down the stairs while trying to swear fealty, inspiring a satirical poem. But in her diary, Victoria dwelt largely on the positives of the event.

Edward VI didn't pay attention to his own coronation

A coronation is a solemn ritual meant to represent all powers of a reigning king or queen, so it's expected that the monarch being crowned be an attentive and dignified part of the ceremony. But how much dignity can you expect a 9-year-old to sustain over several hours of pomp?

Edward VI was a bright and articulate youth, fluent in several languages and a careful diarist, but he was a child when he came to the throne in 1547. During the under-rehearsed pageants and speeches building up to his coronation, according to Chris Skidmore's "Edward VI," he didn't understand the symbolism of the sovereign being given gold and became distracted by a tightrope walker. The coronation itself was cut down to spare the young king's attention span, though many parents today might consider seven hours just as difficult for a 9-year-old to handle as the original 12.

If Edward's imperfect attention can be understood by his age, it's also worth remembering the religious upheaval England found itself in at the time. Edward's father, Henry VIII, had broken with the Catholic church, and the men surrounding Edward were determined to carry forward with the reformation of the Church of England. Records of Edward's coronation are imperfect and contradictory, according to Roy Strong's "Coronation," but there is some indication that the ceremony was abridged and revised for religious reasons as well as the king's age.

Yuan Shikhai's planned coronation triggered a revolt

Yuan Shikhai's relationship with the monarchy of China was long and changeable. A military man, he rose through the ranks of the armed forces in the last days of the Qing dynasty. His survival through various wars, and his part in a modernization campaign, endeared him to the powerful dowager empress Cixi. He briefly fell from power after her death, but was seen as an ideal compromise candidate for the presidency of a new provisional government when the Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911 (per China File).

Yuan, however, was not keen on an imagined parliamentary system, particularly not one where recalcitrant revolutionary parties were impossible to work with. He almost certainly masterminded the assassination of his chief political opponent in 1913, held out against a second revolution later that year, and worked to shore up foreign support, sometimes at the cost of territory. In 1915, he moved to have himself made the first emperor of a new Hongxian dynasty.

In doing so, Yuan greatly misread the mood of the nation. The news he would be officially crowned caused fresh revolts to break out right before the intended beginning of the new dynastic era, and their intensity was so fierce that the planned coronation for February 12, 1916 was indefinitely postponed. Still anticipating an imperial future, Yuan spent heavily on regalia and held a simpler ceremony on January 2, which only increased hostilities. By March, he was forced to abandon all his plans for a new monarchy, and by June, he was dead.

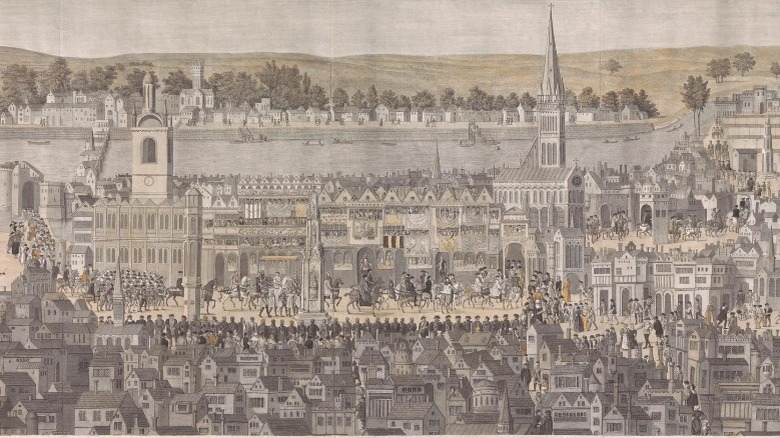

Anne Boleyn faced hostile crowds

Coronations can be held for consorts as well as reigning sovereigns. After Henry VIII ended his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, beginning England's break with the Catholic Church in the process, plans were made to crown his new wife. Anne Boleyn would be the last of Henry's wives so honored. Perhaps the negative reception she received was the reason why.

Henry considered the coronation a necessity; there was widespread hostility throughout his kingdom, and his controversial marital status was just one problem among many. But a ceremony proclaiming the visibly pregnant Boleyn a legitimate queen, and her child a legitimate heir, could mollify at least one grievance. The coronation played out over five days in May and June 1533. The city of London had limited notice ahead of the festivities, and some observers reported underwhelming entertainment.

While admittedly a biased observer and no fan of the new queen, Eustace Chapuys, recorded how badly he believed the event went, saying Boleyn's crowning was "altogether a cold, poor, and most unpleasing sight to the great regret, annoyance, and disappointment not only of the common people but likewise of all the rest, so much so that public indignation has apparently increased by one-half since the said coronation" (via "The Afterlife of Anne Boleyn"). More serious were the accounts that Boleyn was met with either determined indifference by the masses, or by insults and hostility. However, some accounts from Boleyn sympathizers indicate it was a success.

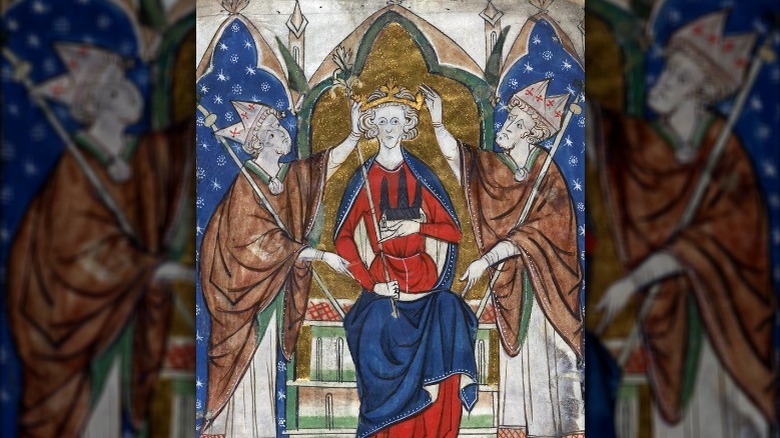

Henry III was crowned with borrowed robes while London was held by rebels

When Henry III came to the English throne in 1216 at just nine years old, it was during a time of crisis. His father, King John (of Robin Hood fame), had essentially given England to the pope, in part to try and thwart the Magna Carta (per David Carpenter's "The Minority of Henry III"). Half the country was in rebellion, favoring Prince Louis of France as heir to the throne on dubious logic. Those lords in rebellion held London at the time young Henry's keepers decided that a coronation of John's son was a necessary check to Louis's well-provisioned malcontents. This meant that Henry III was crowned king in Gloucester, under the supervision of Guala, a papal representative, and Henry's loyal guardian, William Marshal.

Cut off from the traditional symbols of power, Henry went through his coronation with improvised trappings. His "crown" was a circlet that had to stand in for the lost jewels of King John. This cobbled-together ceremony did nothing to change the foreign Louis' advantage among England's nobility. But the church was largely on Henry's side, and he ultimately won over the rebels. Four years after his first coronation, Henry had another, this time in London with full pomp.

Charles X probably shouldn't have had a coronation at all

For Charles X, having a coronation at all was a bad idea. A younger brother of Louis XVI, he had been sent abroad on the eve of the French Revolution and observed its excesses, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the Bourbon Restoration under his brother, Louis XVIII. When it was safe for him to return to France, Charles became a champion of the reactionary royalist faction of the new constitutional monarchy. Despite being out of step with the changes in French society since the Revolution, Charles retained a measure of popularity with his subjects — until he insisted on reviving the ancient coronation rites in 1825.

He could have been warned he was about to step in it, had the committee responsible not been stacked with ultraroyalists (per Vincent Beach's "Charles X of France: His Life and Times"). It was a widespread belief that the coronation offered nothing useful to a France that had changed so much since the last Bourbon crowning. The ceremony wasn't designed to accommodate constitutionalism, and Charles was reluctant to make any changes.

He eventually consented, and he was crowned in Reims with a revised oath and representatives of the new France over May 28 and 29. He specifically pledged to uphold the constitutional charter. But these concessions did not please the masses. The coronation was seen as a ridiculous affair by many of the French, widely mocked, and used as an early weapon by liberal writers in undermining the regime.