Why America's First Paramedics Were So Groundbreaking

The ability to call an ambulance in the United States and know that you'll receive some relevant medical care on the way to the hospital is rather new. Up until the 1960s, the lack of emergency medical services meant that people were more likely to survive an injury in an active warzone than a car accident on a U.S. street.

The Freedom House Ambulance Service revolutionized the concept of emergency medical services. A community-based program, the Freedom House Ambulance Service was focused on not only providing emergency medical services to Black people in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania but on providing working opportunities to some of the most marginalized Black residents of the city. In doing so, the Freedom House Ambulance Service saved lives in more ways than one, with Freedom House paramedics like David Thomas crediting the program for helping him turn his life around, per Opportunity.

Within 10 years, paramedic departments all over the United States were following the Freedom House model. But unfortunately, few of the Freedom House EMTs were able to continue their own work, largely due to the racist attitudes they faced. After the City of Pittsburgh absorbed the Freedom House Ambulance Service, many Freedom House EMTs were forced out of paramedics. John Moon and Mitchell Brown were some of the only Freedom House alumni that continued working in emergency medical services. This is why America's first paramedics were so groundbreaking.

Paramedics before 1960s

Before the 1960s, there wasn't any standardization of care when it came to emergency medical services like paramedics and ambulances. The quality of care varied greatly across the United States. The field of being a paramedic didn't really exist. Instead, when someone called for emergency assistance, police officers or morticians from funeral homes arrived to take people to the hospital, writes Atavist Magazine. Few even had the training to administer aid to people on the way to the hospital and the quality of medical equipment varied greatly, if there even were any. As a result, an incalculable number of people died due to the lack of emergency medical services.

The situation was so dire that in 1966, the National Academy of Sciences released the report Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society, which found that "if seriously wounded, [someone's] chances of survival would be better in the zone of combat than on the average city street." The situation was even worse for Black people who lived in segregated areas, where police would rarely venture to respond to emergency medical calls or would refuse to carry people into vehicles, according to EMS1.

The same year the report came out, the residents of the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania witnessed how even Mayor David L. Lawrence wasn't exempt from becoming a victim to the lack of available emergency medical services when he collapsed and died in November 1966 due to a lack of competent emergency medical services.

Freedom House and Dr. Safar

Dr. Peter Safar, head of anesthesiology at the University of Pittsburgh, connected with Phil Hallen, a former ambulance driver and president of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, in 1966. Safar wanted to deal with the issue of the lack of available prehospital emergency care while Hallen wanted to address emergency services in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, focusing especially on the disproportionate lack of care in Black neighborhoods. Atavist Magazine reports that not only was Safar one of the physicians attending to Mayor Lawrence after he collapsed, but Safar's own daughter had died in June 1966 because of a lack of pre-hospital emergency care, which made the issue of emergency services incredibly personal for him.

Hallen and Safar partnered with James McCoy Jr. of Freedom House, which offered Black-operated jobs training programs and worked together to recruit young Black men, particularly those who were caught under the stigma of being unemployable. The community-based paramedic training program also didn't discriminate against veterans or people with criminal records. The program reportedly recruited people by "[finding] young men who were languishing in the streets and told them what they could become," according to Pittsburgh per EMS World. After a series of psychological evaluations and medical interviews, the very first group of paramedics-in-training started the very first paramedic training course in the history of the United States.

The first paramedics' training course

The first paramedic training course lasted 32 weeks and started in April 1967. The recruits were trained in everything from anatomy and CPR to advanced first aid and defensive driving. They were brought into various hospitals to study and practice and did more rotations than most medical students today. Freedom House paramedic John Moon recalled how Dr. Peter Safar taught him how to intubate in a live operating room with the surgeon waiting beside him. "I was terrified. But Safar believed, what better way to train you to do something than under pressure? We went from room to room doing it," per EMS1.

In "The Ambulance," Ryan Corbett Bell writes that although there were people working in emergency services in different cities in the United States with varying degrees of experience and knowledge of medical techniques, the Freedom House Ambulance Service was "the first to offer the level of training expected of modern emergency medical technicians and paramedics." By October 1967, 20 Black men completed their medical studies and had moved onto on-the-job training to become the first paramedic team.

According to "The Medical Metropolis" by Andrew T. Simpson, the retention rate for people working with the Freedom House Ambulance Service was also high. Out of the 34 people who graduated by 1969, 25 were still working as Freedom House EMTs in 1971.

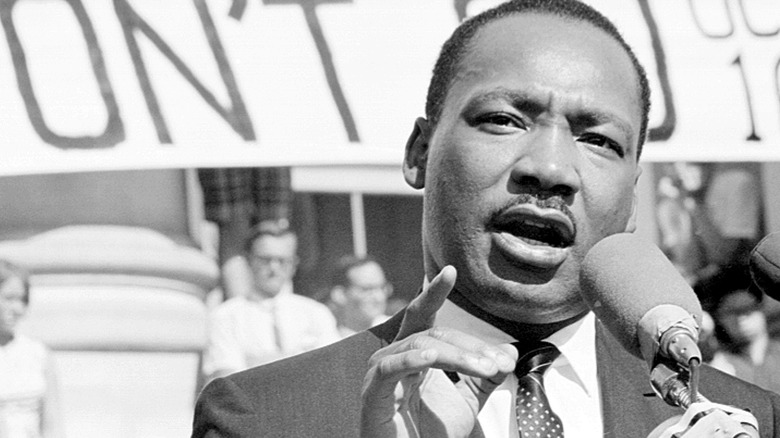

Helping during a 1968 revolt

By the beginning of 1968, the Freedom House EMTs had completed most of their training, but they were still waiting for their ambulances to be designed and made. The ambulances wouldn't be ready in April 1968, when revolts broke out across the United States in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., but even the city of Pittsburgh realized that the Freedom House EMTs could still offer some assistance.

During the 1968 Pittsburgh revolts that lasted until April 11, the Freedom House EMTs rode around with Pittsburgh police officers in police vans to provide emergency medical services to anyone in need. In order to differentiate themselves from police officers seeking to arrest people, they reportedly drove around with their inside lights on.

After the revolts were suppressed, the Freedom House EMTs went back to training. Their first official run came a few months later on July 15, 1968. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reports that after a woman started having seizures on a bus, the Freedom House Ambulance Service raced to respond and took her to the hospital.

Saving 200 people in the first year

It didn't take long for the Freedom House Ambulance Service to start saving lives. They started operating with their own vehicles in 1968 and in their first year of operations, they saved over 200 people who would have otherwise died on the way to the hospital, reports Atavist Magazine.

But the number of overall deaths prevented was likely much higher. Dr. Peter Safer estimated that up to 1,200 people died every year due to a lack of prehospital emergency services, 99 Percent Invisible reports. And because Freedom House focused on both providing care and moving quickly, they were able to prevent many more deaths, with only 1.9% of patients DOA, or dying during transport to the hospital. They were especially known for their prompt arrival times.

On average, the Freedom House Ambulance Service responded to 15 calls a day and transported over 4,500 people in the first year alone, according to the University of Pittsburgh. By July 1971, the Freedom House EMTs were responding to calls in three different districts in Pittsburgh including the Hill District, according to Opportunity. And Black residents even started requesting for the Freedom House EMTs to be sent over instead of police officers.

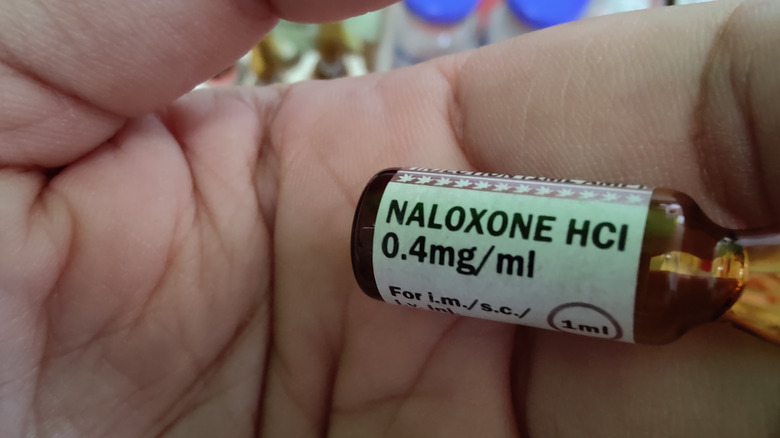

Fewer fatal heroin overdoses

The efforts of the Freedom House EMTs also led to a significant reduction in fatal heroin overdoses in Pittsburgh communities. Before the existence of the Freedom House Ambulance Service, EMS World writes that communities wouldn't trust the police with drug overdose calls. But now not only were the Hill District residents more likely to call for Freedom House EMTs during an overdose since they wouldn't face any legal consequences, but Freedom House EMTs educated local drug dealers about overdoses as well. As a result, the number of fatal heroin overdoses in Pittsburgh dropped significantly while Freedom House was in operation.

The Freedom House EMTs also pioneered the use of naloxone in the form of Narcan during emergency services, becoming the first paramedic group to administer naloxone during overdoses. The heroin epidemic in Pittsburgh during the mid-1970s affected both white neighborhoods and Black neighborhoods. But because the Freedom House EMTs were trained in how to administer Narcan, the number of overdoses in the Black neighborhoods serviced by Freedom House was significantly less than those in white neighborhoods.

Working with limited resources

Despite making incredible strides in establishing the field of paramedics, the Freedom House EMTs struggled to help everyone in need given their limited resources. Atavist Magazine reports that although the City of Pittsburgh agreed to contribute $100,000 a year to Freedom House Ambulance Services to subsidize their services, Mayor Pete Flaherty decreased the city's contribution to $50,000 when he took office in 1970. And although the city's contribution was supposed to be paid monthly, one year Freedom House didn't receive any contributions until November. And although Freedom House technically charged residents for their EMT services, they rarely went out to collect on the debts.

The Pittsburgh police department also posed an obstacle to the Freedom House EMTs. Although the police were supposed to forward calls from the Hill District and other Black neighborhoods to the Freedom House EMTs, they often refused to do so. And 99 Percent Invisible writes that police resented the Freedom House EMTs and sometimes threatened the EMTs with arrest when they showed up at the scene of an emergency. Dr. Peter Safar later wrote in his memoirs that "racial prejudices with white police officers eager to maintain control of ambulances city-wide" for the poor treatment that Freedom House EMTs received.

Mayor Flaherty also went on to impose a policy of no sires in downtown Pittsburgh, effectively keeping the Freedom House ambulances from being able to move through traffic and reach people before the police during emergencies.

Dealing with racist patients and doctors

The Pittsburgh Police Department and the mayor's office weren't the only racist obstacles that the Freedom House EMTs confronted. While they were initially training to be paramedics, doing rotations in various departments, the Freedom House paramedics-in-training were often thought to be janitors instead of students, per Atavist Magazine. And even when the Freedom House EMTs were fully trained, doctors sometimes refused their advice and help. Freedom House paramedic John Moon recalls at least one time when a white nurse laughed in response to him reading someone's vital signs.

In addition to hospital personnel, the Freedom House EMTs also faced racist patients when they were called into white neighborhoods. Sometimes, even when white people were facing a severe medical emergency, they'd refuse to allow the Freedom House EMTs to touch them.

In an interview with America Dissected, writer and former paramedic Kevin Hazzard describes how people would be told that if they didn't allow the Black person to touch them, there was a chance that they could die, "And there's a hesitation there. And in that hesitation between dying and allowing Black men to touch me is kind of all you need to know about how complicated the situation was. And, you know, that's the environment in which they were trying to practice medicine."

The disaster drill

The real demonstrative show for the medical community of the Freedom House Ambulance Service came on May 9, 1975. During an international symposium on emergency medicine, the Freedom House EMTs put on a demonstration of how they would respond to a severe multi-vehicle accident. The disaster drill was executed so well that the Freedom House EMTs were described as "the most skilled and sophisticated in the nation," per Atavist Magazine.

After the presentation of the Freedom House EMTs' skills, its medical director Dr. Nancy Caroline was contracted by the U.S. Department of Transportation to write the first national curricula on emergency street medicine. And in an article in The University of Pittsburgh's Pitt Med Magazine, Chuck Staresinic writes that Freedom House EMTs were subsequently involved in the testing and implementation of the new national curricula standardizations of EMT training and ambulance equipment.

Unfortunately, the very same year that the Freedom House EMTs showed the entire United States medical profession what they were capable of, the city of Pittsburgh decided to revoke their funding.

The Freedom House model

Cities across the United States soon started following the Freedom House Ambulance Service model. Although other cities had been trying out their own emergency medical service programs, they were soon copying the Freedom House model due to its efficacy. This was due to the Freedom House ambulance design, which included equipment usually found in emergency rooms, as well as the fact that Freedom House EMTs were trained in intubation early on. EMS World also writes that the Freedom House ambulance design was so revolutionary that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration adopted its layout as the official standard.

Paramedic and filmmaker Gene Starzenski has stated that "Freedom House was the leader, and because of them Pittsburgh developed into one of the leaders in EMS." Unlike other burgeoning paramedic programs which focused on only a handful of emergency situations, the Freedom House EMTS made it standard procedure for EMTs to be ready to deal with a wide array of life-threatening emergencies.

The Freedom House EMTs also caused a chain reaction in the medical system. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, as cities adopted the Freedom House model, doctors and emergency rooms also updated the care they were giving patients, like adopting triage systems. Both Dr. Peter Safer and Dr. Nancy Caroline also went on to continue working on spreading the standardization of the EMS system. Unfortunately, the Freedom House EMTs wouldn't be given similar opportunities after the Freedom House Ambulance Service was disbanded.

What happened to the Freedom House paramedics?

Despite its many achievements, the Freedom House Ambulance Service was shut down in 1975. According to Atavist Magazine, Mayor Flaherty had already announced a plan a year earlier to train police officers into being paramedics, with the implication being that Freedom House wouldn't be funded once that existed.

In October 1975, the funding for Freedom House Ambulance Service was officially stopped. The City of Pittsburgh established its own paramedic system and although Dr. Nancy Caroline made the city agree to hire the Freedom House EMTs, the city soon found ways to get rid of all of them. EMS World reports that the Freedom House EMTs were subjected to new tests, sometimes on a weekly basis, on completely new material. Those who failed were fired, as were those with criminal records. Some were re-assigned, though typically to non-medical jobs. Some also quit in response when white coworkers with no experience were promoted over them. As a result, 99 Percent Invisible writes that up through the 1990s, 98% of the people working at the Pittsburgh EMS were white.

Unfortunately, after the Freedom House Ambulance Service was disbanded, Dr. Peter Safer focused his attention on national EMS standards rather than continuing to prioritize community-based care. According to The New England Journal of Medicine, this prioritization "set the tone for subsequent national structuring of police and emergency response systems, which relegated these functions to mostly White male professionals from outside the communities they serve."