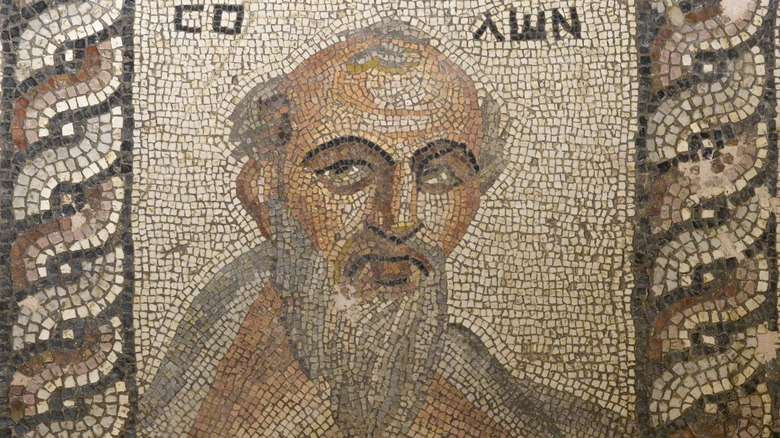

Who Was Solon, The Greek 'Father Of Democracy'?

When folks think of the word "democracy," they might think of Founding Father dudes wearing throat-ruffled coats while standing around a table and signing documents — at least for those living in the U.S. Other countries have their own democratic figures, either revolutionary or lawfully elected. Meanwhile, nations like Russia have only had a meager eight years of vaguely democratic rule — from 1991 to 1999 after the Soviet Union fell and before Vladimir Putin took power — out of thousands of years of history. At this point even words like "democracy," "republic," "justice," "rights," and other related concepts have taken on blurred lives of their own and evolved from their original meanings. "Democratic rule" changes depending on the listener, junction in time, and those implementing supposed by-the-people policies.

So what did democratic rule look like in its original form, some 2,500 years ago in ancient Athens? Not that governance-by-committee societies didn't crop up elsewhere, but such records are scarcer and their impact minimal in comparison. Aside from granting us live theater, gorgeous artwork, a history of philosophical and scientific inquiry, and poetic work that will outlive all of us living, the Greeks in Athens gave us democratic rule — after a fashion. Athenian citizen governance inspired the Romans, who inspired the Renaissance (particularly in Florence), which inspired the European Enlightenment, which passed democracy to us. And at the start of it all was Solon, sometimes dubbed the "Founding Father" of democracy.

Draco's draconian law code

Before you go thinking that Solon presided over a utopian freedom-fest where folks lounged around in robes all day — not exactly how a functional society could ever operate — bear in mind that none of his democratic reforms were ideal by current standards. That's because democracy itself has never been, nor will ever be, ideal. For the purpose of this article, it's best to think of democracy as a protean concept that shifts, in definition and practice, according to the needs of the day. Society isn't perfectible because people aren't perfectible. And without the long path of history — whatever that path is, including Solon and ancient Athens — we've got nothing.

For the sake of ease, it's best to start in the 7th-century B.C.E with Draco, a harsh, brutal Athenian lawmaker whose reign predated Solon by about 30 years. Draco — from where we get our modern word "draconian," meaning "cruel" or "severe" (per Merriam-Webster) — lived in an era of loose traditions and blood feuds, not codified laws. Draco set to task standardizing punishments for various crimes. In many cases, even for minor crimes, the punishment was the same: death. He finished writing his law code in 621 B.C.E. on the final year of the 39th Olympic Games. But it wasn't long before the people grew uneasy with Draco's rather cruel and overreaching code and elected someone new into the governor-like position of archon: Solon.

Archon in a time of economic crisis

Information about Solon's life comes to us from sources like Plutarch, the Greek historian who lived about 700 years after Solon's time. According to World History Encyclopedia, Solon had taken on a near-mythical role in Greek history by then, and that's exactly the kind of magnanimous, romantic colors that Plutarch used to paint him. But regardless of the exact separation of fantasy and fact, Solon's impact remains the same.

By all accounts, Solon — pronounced with a long "o" in the first syllable, like "soul on" — was the fairly well-to-do son of another lawgiver, Execestides. Solon was a merchant in his younger years and a sort of traveling poet, a habit that he kept up in his later years and which grants us much of his writing in the form that he preferred: poetry. The Canadian Museum of History tells us that Solon had a reputation for being wise, and this is why he was elected to the governmental position of archon in 594 B.C.E. It's a good thing, too, because Athens was in the middle of an agriculture-based debt crisis at the time. The majority of people worked land that belonged to the few aristocratic wealthy and had to hand over one-sixth of their crops. If they couldn't do it, they or their family could be sold off as enslaved people. And so one of Solon's first moves as archon? He straight-up canceled all debt.

A pervasive sense of justice

World History Encyclopedia explains Solon's other reforms, and to say that they're remarkable and impressive is an understatement. After canceling everyone's debt, he went two steps further: He forbade anyone from being sold into slavery if they couldn't pay back their loans in the future, and he also freed all current debt-owned enslaved people. He then completely overhauled the Athenian economic system, which — in a rocky, hilly environment — was almost wholly dependent on agriculture. In short, he created different tiers of wealth (kind of like tax brackets) for different levels of food production. He also tied political office to the higher brackets, a move that kept the wealthy happy and the poor safe from their ire.

Such a nuanced sense of ethics and justice seems to have been characteristic of Solon. As he himself wrote in poetic verse (per World History Encyclopedia), "To the mass of the people I gave the power they needed / Neither degrading them, nor giving them too much rein / For those who already possessed great power and wealth / I saw to it that their interests were not harmed / I stood guard with a broad shield before both parties / And prevented either from triumphing unjustly."

Solon then drafted a full law code that overturned Draco's harsh punishments except in cases of murder. He regulated trade, balanced the economy, and created laws regarding inheritances and funerals, adultery and theft, injury and property damage, and the overarching democratic processes of Athenian government.

Widespread reforms to law and government

Amongst some of Solon's other reforms — all based on fundamental notions of fairness — were overhauls to the Athenian military and judicial system. Like modern-day Greece, Athens required mandatory military service of its men. But in another revolutionary move, Solon prevented people in the lowest economic tier — of four, remember — from participating. This is because military personnel had to pay for their own custom-made armor, weapons, and horses and because their families would be financially ruined if their breadwinners died. The two wealthiest social classes could become cavalry because they could afford it. But even among the lower of the eligible military classes, only the most physical fit could join, and even then the state treasury covered his and his family's expenses during times of war.

Judicially, Solon implemented an open-forum grievance court called the Heliaia, where members of all classes — from the lowest to the highest — could state their concerns on equal footing. And in a shockingly bold decision, the court even allowed people to charge their superiors and members of the government with crimes. This assembly functioned as a final, supreme court-like body composed of 6,001 members. While such changes to Athenian life didn't prescribe each nitty-gritty of the city's democracy — folks like the philosopher Aristotle called Solon's codes too vague — they paved the way for the very notion of democratic rule.

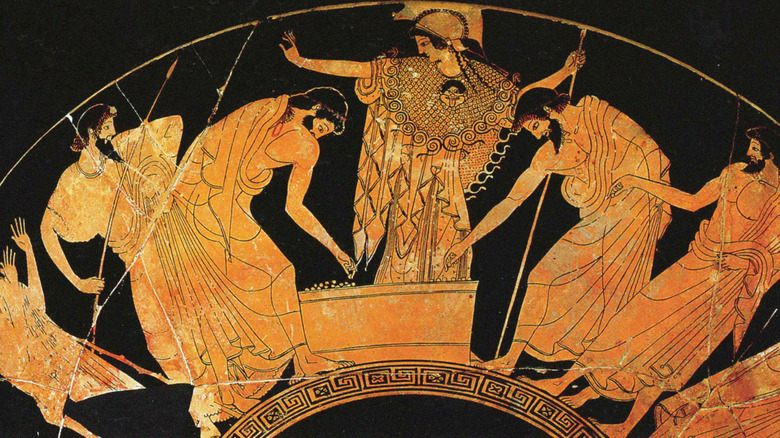

The city of the goddess of wisdom

Solon's reforms set the precedent for Athenian civil and political life that carried Athens into its Golden Age from 480 to 404 B.C.E. Many have rhapsodized about the vibrancy, creativity, and uniqueness of that time and its impact on history, as articles like that on The Atlantic do in spades. While ancient Athens — with its art, literature, theater, philosophy, and yes, democratic rule that was revolutionary for the time — was "not very numerous, not very powerful, not very organized," the city still "had a totally new conception of what human life was for, and showed for the first time what the human mind was for." This is apropos considering that Athens' patron goddess, and the one after whom the city is named, is Athena, the warrior goddess of wisdom.

By 507 B.C.E., over 50 years after Solon's death, Athens was well on its way to becoming what history remembers. That year, the politician Cleisthenes first used the term "demokratia" to describe his particular system of reforms: a neologism History says formed from combining "demos" (the people) with "kratos" (power) into a "rule by the people." While every single one of Athen's 100,000 citizens didn't have a voice — assemblies were limited to free men over the age of 18 — each of those individuals directly and mandatorily gathered to vote on issues of state. That's why in referencing Athens, the historian Herodotus coined the phrase "equality before the law."