Messed Up Things At Woodstock

It was three days of peace and music, and also mud, drugs, burned eyeballs, traffic jams, and overflowing toilets. But, you know, peace and music.

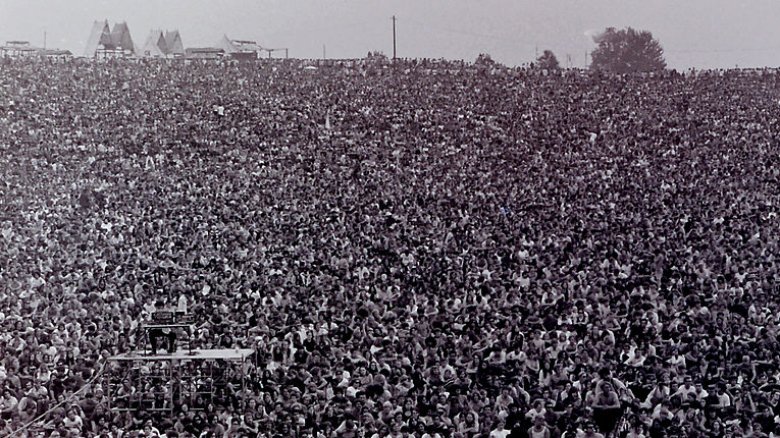

The Woodstock festival of 1969 remains one of the most iconic events in music history, and as the decades pass those who were there start to see it all through stardust-sparkly lenses, or something, while totally forgetting about the fact that it was mostly not really very much fun. Now, there were a lot of positives, and not just the unforgettable musical performances (provided you were close enough to the stage to actually see and hear them) but also the part where the world found out that it's actually possible for half a million people to get together without a single fistfight, at least not as far as anyone can remember. But that doesn't mean that the festival was all dancing, holding hands, and putting flowers in everyone's hair, either. There was lots of crap at Woodstock, and some of it was even literal crap.

Death by sewage removal equipment

Let's just start with the single most messed up thing that happened at Woodstock and then work our way backward. Seventeen-year-old Raymond Mizsak, who was attending the festival with his older sister, was in his sleeping bag at 10:30 a.m. on the second day of the festival when a tractor towing a water tank trailer on its way to drain the porta-potties rolled right over the top of him.

Now this sounds like gross negligence, but in the driver's defense, Mizsak wasn't exactly in an obvious place. A 1995 article in the Times Herald-Record said the hill where the teen was sleeping was covered in a "pile of soaked garbage and sleeping bags." Mizsak had put his sleeping bag over his head to keep the rain off, and the driver hadn't been able to distinguish between the one with a person in it and all the abandoned sleeping bags mixed in with the garbage.

A helicopter was called in to transport Mizsak to a hospital, but when it showed up he was already dead. Not only was his death tragic and senseless, but on the list of totally sucky ways to die, getting run over by a porta-potty tanker in a pile of garbage is probably right up there with getting eaten by a hyena and impaling yourself on a baguette as one of the suckiest ways to die ever. At least he slept through most of it.

One toilet for every 833 people

Imagine going to a concert and having to wait in line to use the bathroom. Oh, wait, that's reality. A modern stadium might have one toilet for every 45 or 50 seats, which is a great system in the fantasy land of "not everyone is going to have to go at the same time," but it doesn't take into account the fact that during intermissions, everyone goes at the same time. But still.

At Woodstock, there was one toilet for every 833 people, which means standing in the bathroom line was about 18 and a half times suckier than standing in the bathroom line at a modern stadium, and that's if you're only taking into consideration the standing-in-line part. Modern stadiums have flush toilets, and Woodstock had porta-potties, so you can add an exponential amount of suckiness to the basic standing-in-line suckiness when you consider that that many people using a single porta-potty is going to create some seriously disgusting problems.

According to ThoughtCo, the wait for a toilet could take up to an hour, and by the time you got there you were probably wondering if it would be better to just go find a quiet bush somewhere, since the toilets were all overflowing and raw sewage was collecting in puddles, mingling with all the mud and running downhill. So the next time you're tempted to complain about the lines at MetLife Stadium, just don't. It could be so much worse.

Let there be granola

Today, everyone knows there's no better way to make a few thousand bucks in a weekend than to make people wait in ridiculously long lines for crappy, overpriced food. But at Woodstock, would-be vendors just didn't have the foresight to recognize how much money there was to be made.

According to the Smithsonian, the established food vendors didn't want to have anything to do with the festival, mostly because of its projected size. So organizers settled for three dudes who called themselves "Food for Love" and had almost no experience as vendors. By mid-Saturday, they were running out of food, so they did what any self-respecting capitalists would do — they quadrupled their hot dog prices from 25¢ to $1. And then a bunch of peace-loving hippies burned down two of their concession stands because they were annoyed about the long lines and outrageous prices.

Now, it's definitely annoying to wait two hours for a taco made from canned beans and beef that's been sitting in a warm ice chest for half a day, but a dollar for a hot dog seems like a bargain compared to nine and a half dollars for a couple tacos. Inflation seems to have hit food vendors especially hard since the late '60s.

Happily, the day was saved by a group called The Hog Farm Collective, who passed out thousands of cups of granola and saved everyone from starving to death.

The free festival that wasn't actually supposed to be free

Ultimately, it's pretty clear that the major cause of the festival's woes was just pure lack of organization. Perhaps if organizers had just asked themselves, "What are the top money-losing mistakes we might make? Let's rank them in order of things we'd better not accidentally do," then maybe, just maybe, they wouldn't have lost a million dollars. And that's not an exaggerated figure, by the way.

According to ThoughtCo, the festival was originally supposed to take place in Wallkill, New York. But residents of Wallkill basically said, "Hell, no, we don't want a bunch of hippies in our town with their acid and their mary-ju-wanna, let's pass a law." So they did, and organizers had to find another venue with just six weeks left on the clock.

Happily, or maybe unhappily, depending on if you were the one who stood to lose a million dollars, a dairy farmer in Bethel offered up some land. The stage, parking lots, concession stands, and a children's playground got finished just in time, but for some reason organizers didn't think to prioritize gates and ticket booths on their list of "top money-losing mistakes we might make" and by the time 50,000 people just walked right in and camped out next to the stage, it was a problem that could no longer be fixed. So Woodstock became a free festival — a mistake that would turn out to be financially devastating for its organizers.

Involuntary tripping

The 1969 Woodstock festival was famous for the mud and the music, but it might have been even more famous for the drugs. Not everyone who went to Woodstock actually wanted to do drugs, though. For some it was totally involuntary. People weren't just selling drugs, they were putting them in stuff that they then handed out for free, which was probably awesome if you were looking to get high but was extraordinarily sucky if you weren't.

"Outside [the tent] they were giving out electric Kool-Aid laced with whatever," a nurse told the Times Herald-Record. "Now, when kids take a tab of acid, they know what they're getting into. When you drink something that's cold because you're thirsty, that's different. A lot of the kids hurt with this stuff were just thirsty. They didn't have any choice." So maybe dealers thought they were being charitable with all the free drugs — peace and music, man — but when you're just a thirsty kid who can't even pronounce "lysergic acid diethylamide," getting a surprise dose of LSD is pretty unspeakably cruel.

Woodstock organizer Michael Lang recalled being extra careful about everything he consumed at the festival, because laced food and drink was everywhere. "I didn't drink anything that didn't come from a bottle I didn't wash or open myself," he later said. Which is pretty wise, although getting high would have at least taken his mind off all the money he was losing.

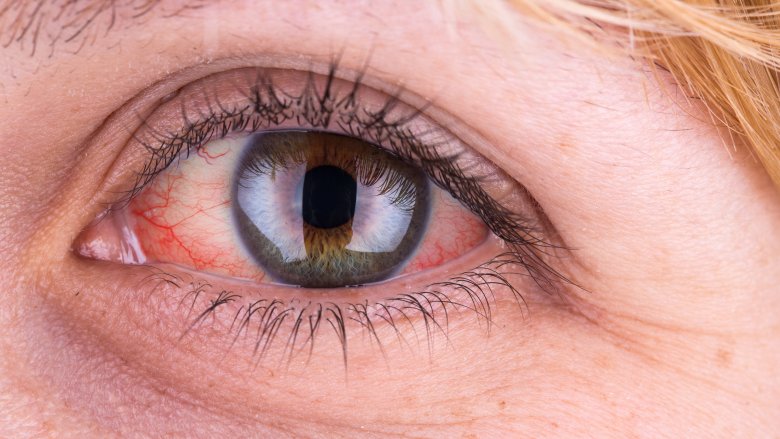

Burned out ... eyeballs

Snopes says the old stories from the '60s about kids taking LSD and staring at the Sun until they went blind is completely bogus, probably just a hoax perpetrated by "individuals who possibly share [the media's] zealotry for evoking before the public's terror-charged eyes the many perils presumably awaiting the hallucinogenic traveler."

On the other hand, there was a nurse at Woodstock who reported that burned eyeballs were actually a thing at the festival, and that they appear to have resulted from kids on LSD who would "lie down on their backs and just stare."

Now whether this is also part of the great hoax against hallucinogenic travelers is still in question. The original stories about burned eyeballs appeared a couple years before Woodstock and were debunked in a book called The Pleasure Seekers, which was published just after the festival. But it does seem strange that a random nurse would make up a similar story, unless she was so horrified by the drug use that she felt a little extra fictionalized horror might dissuade future "travelers."

The nurse did say there were "five or six or seven [patients] at a time," so it was either a very big made-up story or a very minor epidemic. Evidently it was enough of a problem that there was a whole medical area devoted to treating burned eyeballs, though no one says whether the damage was permanent.

The hippie apocalypse

The scene on the roads leading to the festival was roughly similar to that long shot they used to play in the opening credits of The Walking Dead, with lines of abandoned cars clogging the freeway out of Atlanta. (You could say Woodstock actually was a little bit like a scene from the zombie apocalypse, what with all the filth-covered people in altered states staggering around being hungry all the time.) Politico calls Woodstock one of the top 10 worst traffic jams ever — the traffic was jammed up for 10 miles on the New York Thruway for the entire three days of the festival. Some people even abandoned their cars and walked in, turning the freeway into a parking lot.

The traffic impacted the festival in more ways than just making everyone cranky. Some of the big performers had to be flown in via helicopter because they couldn't get in by land. Residents along the roads were trapped in their homes because abandoned cars were blocking their driveways. Meanwhile, would-be festival-goers looked for places to camp along the road, which sometimes ended up being people's backyards. At least there were more bathrooms per capita what with all the houses around.

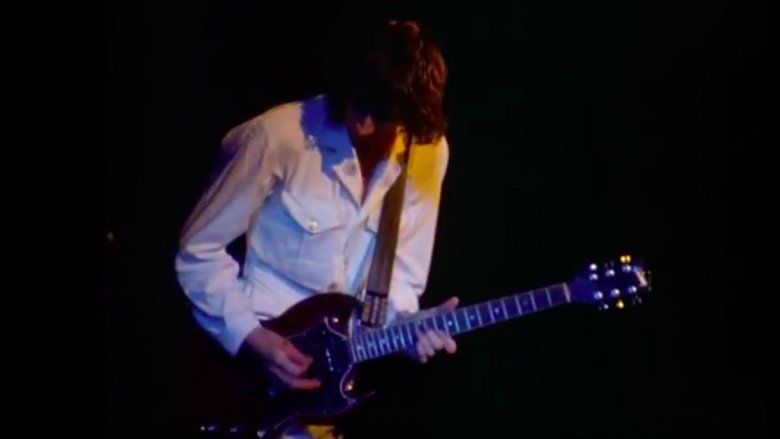

The Grateful Dead's shocking performance

There were a ton of people who said the Grateful Dead was one of the worst acts at the festival — even Jerry Garcia's friend Phil Ciganer couldn't be charitable, later declaring, "It was the worst show of theirs I'd ever seen." But you do have to cut them some slack. Let's say that you were at work doing whatever it is that you do, whether it's singing, waiting tables, or writing articles about overrated musical festivals that happened before you were born. If you were doing that job while standing in water, and the tools of your trade — whether it's your computer keyboard or plates full of food — were actually giving you an electric shock every time you touched them, it'd probably be the worst job performance of your career, too.

"It was a very terrible moment for us," said drummer Mickey Hart. "The stage was collapsing. It was raining. Jerry [Garcia] and Bob [Weir] were getting shocked at the microphones." According to Today, the Grateful Dead's sound engineer remembered Bob Weir "jumping back five feet from electrical shock when he went up to touch the microphone the first time." So just in case you think all those rats in mazes experiments prove that electric shock improves performance, well, The Grateful Dead begs to differ. Of course, there wasn't any cheese to reward them at the end of the show either, but still.

Okay, there was a little violence

Woodstock mostly was peaceful, even though there were plenty of reasons for it not to be. No one fought anyone over the last outrageously overpriced $1 hot dog. No one got punched for trying to buy their way to the front of the porta-potty line. But there was one notable instance of violence involving a guitar and someone's head.

According to the Huffington Post, during The Who's performance, a political activist named Abbie Hoffman got on stage and took the microphone, and started ranting about brothers and sisters and persecution and blah, blah, blah, or at least that's what The Who's Pete Townshend was thinking because he only tolerated a few seconds of insolence before he hit Hoffman in the head with his guitar. In one version, Hoffman looked at his assailant and then jumped off the stage and walked away; in another version, Townshend actually hit him hard enough to knock him off the stage.

But really, if you add that little incident in with the burned down concession stands and maybe an argument or two about who could stare at the Sun the longest, there just wasn't a lot of violence anywhere in that throng of 500,000 people, which is perhaps one of Woodstock's most remarkable legacies.

Put some shoes on, hippie

Meanwhile, the medical teams were super busy. According to the Journal of Emergency Medical Services, the local practitioner who'd been hired to oversee them declared the event had the potential to become "the greatest medical tragedy of our times." That wasn't just because the medical team was only set up for a crowd of roughly 50,000 people and 500,000 showed up, but also because the clogged roads meant they wouldn't be able to get any ambulances to or from the site if all the peace and love ran out and people started rioting.

Fortunately, the "greatest medical tragedy of our times" didn't materialize that weekend, but that doesn't mean that bad things didn't happen. By the end of the festival, medical staff reported they had treated 797 bad trips, 23 epileptic seizures, 57 cases of heat exposure, and 176 asthma attacks. There were also 938 foot lacerations, 135 foot punctures, and 346 random other foot injuries, all of which basically just served to prove that hippies really ought to wear shoes. CNN reported that a woman also fell from stage scaffolding and broke her back.

Remarkably, only two people died — the 17-year-old who was killed by the sewage-toting tractor and a Marine who died from a heroin overdose. Of course by today's standards, even one preventable death at a festival would be considered outrageous, but for a team that got 10 times more than they'd planned for, two dead out of half a million really isn't that terrible.

Trip tents

Because lacerated feet, heat exhaustion, and people getting run over by tractors just wasn't enough to keep them all busy, the medical team also had to set up separate tents just to treat people who were having bad trips. According to the Journal of Emergency Medical Services, one newspaper estimated there were around "25 freakouts each hour," and since freakouts could last several hours, these patients started filling up the tents pretty quickly.

Unfortunately the Woodstock medical team wasn't really that experienced with LSD "freakouts," so they enlisted the help of the Hog Farm, yes, the same people who passed out all the granola. The Hog Farm provided 85 people who were all experienced in running "trip tents" at similar festivals. The Hog Farmers had developed a technique for talking down bad trips, which was remarkably successful and also saved them from having to use Thorazine, a seriously hard-core tranquilizer and anti-psychotic drug commonly used to treat bad trips in emergency rooms.

In hindsight, most people fail to recognize just how important the medical services were, and how equally important it was for doctors and nurses to remain non-judgmental in the face of so much recreational drug use. Because of that, people experiencing drug-related side effects weren't afraid to seek help, which meant they would get the care they needed, but also helped prevent any widespread panic that would have definitely gotten in the way of all the mud-soaked peace and music.

The documentary was the dividing line between legendary and forgotten

Everyone remembers Joan Baez, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, Keef Hartley Band, and Quill. Wait, you mean you don't remember those last two? Maybe it's because those bands — although they did indeed play at Woodstock — did not get featured in the documentary film Woodstock. That means that they braved the mud and the electrically-charged sound equipment and ended up with very little name recognition for their troubles.

According to Huffington Post, the four-hour, Oscar-winning documentary, which was released the year after the festival, gave a publicity bump to the bands we now think of the big-name performers of the era. Bands who were left out of the film were largely forgotten. And some of the artists who gave kind of patchy performances — like the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin — got excluded from the original film but were acknowledged in later releases, which gave them a sort of belated publicity bump. So really, it wasn't Woodstock itself that turned those already-big names into legends, it was the documentary film about Woodstock. After all, the memories of 500,000 stoned hippies may fade, but film is forever.

A midnight loan saved the festival

The Woodstock festival was a generation-defining, epic historical moment, which became enshrined in musical history and the collective consciousness of America. But for organizers, it pretty much sucked.

It's probably safe to say that the four guys who put the festival together really had no idea what they were getting themselves into. They were all in their 20s, and the only real qualifications they had were green with pictures of presidents on them. When they finally settled on the idea of putting on a concert (after cycling through other ideas like building a music studio and filming a sitcom), they decided the best way to get big names was to offer double the money that those big names usually got. They were already kind of over their heads even before the festival turned into a free-for-all. But then, traffic became such a problem that they had to contract helicopters to fly in food, supplies, and their very expensive performers.

According to History, it got so bad that the festival was nearly canceled, because by Saturday some of the performers were having temper-tantrums and demanding upfront pay, in cash. So, organizers convinced a local bank to front them an emergency midnight loan, using a personal trust fund as collateral. And the show went on, though it probably was only bittersweet for the organizers, since the loan wasn't exactly going to help them turn a profit... just prevent 500,000 people from getting really pissed off.

In 1969, hippies weren't really that into the Earth

Today, we think of hippies as gentle souls who believe in peace, love, and taking care of Mother Earth. In the late sixties, hippies were mostly just about the first two items on the list, and not so much about the third. Unless they maybe just didn't think of Max Yasgur's dairy farm as "Mother Earth," necessarily.

At any rate, the people who went to Woodstock did not, for the most part, seem to give an actual crap about the environment at the festival. According to a 1969 article in The Village Voice, there were still "piles of garbage up and down the hillside" a month after the festival, one of which was "still smoldering."

There was evidently some effort to keep the site clean during the festival — trash bags were passed around through the audience at various points — but it wasn't enough to keep the garbage from inundating the nearby woods and the shoulders of most roads. Photos of the aftermath show volunteers filling bags with trash during the last days of the festival, and local people cleaning up the debris that was left in front of their homes and neighborhoods. Perhaps organizers should have billed the festival as "three days of peace, music, and sanitation." That might have at least saved them something on the cleanup.

Peace and music won't stitch up a serious laceration

The traffic wasn't just a problem for people who really, really wanted to get to the festival — it was also a problem for emergency services. One image from the event shows a young man sprawled out on the pavement, surrounded by stopped cars and good Samaritans. According to the image caption, he was "thrown from the trunk of a car," but an ambulance wasn't able to get to him because there was just no way through the traffic.

Now, let's just ignore the part where he was "thrown from the trunk of a car," because we're not really sure how that actually happens unless the trunk latch is broken and you're a bag of groceries. But the fact that there was no way in for emergency services just sort of highlights the miracle of Woodstock — that there weren't considerably more deaths and/or serious injuries. Instead of being remembered as a generation-defining, epic historical moment, Woodstock could have been remembered as one of the great tragedies of the 20th century.

Three days of hell... err, peace and music

It was billed as "three days of peace and music," but it's probably more accurate to say that it was "three days of mud, rain, and food shortages." Festival-goers might have been super enthusiastic on Friday, but on Sunday, a lot of them had pretty much had it. So, by the time headliner Jimi Hendrix got on stage, the crowd had dwindled from a peak 500,000 down to around 180,000.

It kind of comes down to the failure of concert organizers to get pretty much anything right — the schedule was so badly mucked up by Sunday that performers were taking the stage literally hours after they were scheduled to appear. According to History, Hendrix had a clause in his contract that virtually guaranteed most fans would miss his performance. No one was allowed to perform after him, and since Sunday's schedule was so hideously delayed, he didn't get on stage until Monday morning... which, incidentally, was the fourth day of the three-day festival. Although he gave what is widely considered to be a legendary performance, including his famous rendition of "The Star Spangled Banner," most of the exhausted, hungry, dirt-covered people who came to see him had already given up and were on their way home. In fact, it's probably safe to say that a lot of them weren't even aware of what they were missing.