Francisco Goya's Creepy Black Paintings Explained

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, more often referred to as Francisco de Goya or simply Francisco Goya, is one of the most remarkable figures in the history of Spanish art. Born in the town of Feundetodos on March 30, 1746, the talented young artist studied in both Spain and Italy before establishing himself as a public painter in the city of Zaragoza, and later at the Spanish court. He later worked on more controversial works, including nudes and paintings offering dark critiques of the bloody Peninsula War between Spain and France, which came to be counted among Goya's best.

But despite his success as a court artist, the last years of Goya's life were difficult. Disillusioned by the restoration of the Spanish monarchy under King Ferdinand VII, Goya, who was suffering from failing health and deafness, lived from 1820 to 1823 as an almost total recluse in a house not far from Madrid, known as the Quinta del Sordo, or the "Villa of the Deaf Man."

Goya decorated the walls of his home with a series of frightening works later known as the "Black Paintings." Discovered only after the painter's death and with no notes or titles provided by Goya himself, scholars have long puzzled over what these dark images actually represent. They are now some of the most famous paintings of all time, as well as some of the most grotesque, symbolically charged, and enigmatic. Here is what the art world has to say about them.

Atropos (or The Fates)

The 105-inch-wide mural that is commonly referred to as "Atropos," or "The Fates," is a work representative of several of the issues that arise when it comes to approaching Francisco Goya's elliptical Black Paintings. For instance, the painting, like many in the series, is known by two titles that alter the meaning of the painting as the viewer encounters it.

In classical Greek mythology, the three Fates were sisters and goddesses of destiny who together measured human lives as pieces of thread and plotting the paths they take. Atropos is the name of one of these goddesses, whose name translates from the Greek as "unalterable," a reminder that mortals are immutably bound to their lives which have a set duration. It is perhaps no surprise that Goya would have been attracted to this subject in the final years of his life, and that he would render the fates disturbing and grotesque.

The Goya scholar Robert Hughes offers one of the most compelling analyses of "Atropos," noting that though the painting alludes to a mythological scene, Goya alters its representation, painting four figures, not the mythical three, opening the painting up to new interpretations. He notes that while the three surrounding Fates are shown handling the thread of life, the central figure that looks out at the viewer appears to be tied up, perhaps representing human life as a helpless victim of fate. Though it has been speculated that this may be an intertextual reference to another myth — of Prometheus — the figure also offers an insight into Goya's state of mind, and his feeling of being trapped by ill-health and old age.

Two Old Men (or Two Monks)

Francisco Goya's declining health is also believed by many to inform another of his Black Paintings, "Two Old Men," also referred to by several scholars as "Two Monks." He had come close to death in 1819 but was saved by a devoted physician known as Dr. Arrieta, for whom Goya composed a self-portrait with the doctor at his side, reviving him with smelling salts. That painting included a number of shadowy background figures that have been interpreted as friends by some critics and demons by others: and the same range of interpretation is arguable for "Two Old Men."

Despite the rather quotidian titles attached to the painting in question, which both suggest that those depicted are alike, there is something unsettling occurring between the two figures. One is certainly an old man in religious dress, leaning on a crook. But beside him is a creature that can barely be described as human, leaning into the old man and talking, or quite possibly shouting, into his ear.

Robert Hughes notes that the wide-mouthed figure carries hallmarks of how Goya depicted demonic creatures in his other works, such as its exaggerated mouth, and that the figure's shouting suggests the old man's deafness, suggesting that the old man represents Goya himself.

Two Old Ones Eating Soup (or Two Witches)

The Black Painting commonly referred to as "Two Old Ones Eating Soup" is similar to "Two Old Men" in both its apparent portrayal of old age and decrepitude, as well as the fact that the title fails to suggest the unnerving darkness that pervades the work in question.

Only one of the two people represented in the painting appears to be eating soup, while staring with a look of alarm or perhaps pain past the left edge of the canvas. The other deathly figure is slumped on the table, and, were it not for the title, would almost certainly be interpreted as a corpse by the vast majority of the painting's viewers. The scholar Fred Licht speculates that the drama of the painting comes from the fact that "Two Old Ones Eating Soup" was not created by Goya in an attempt to portray a familiar scene for the viewing public, as traditional public painters do. Instead, Licht argues that Goya is engaged in a personal interlocution with ideas that "possess" his imagination, rendering them existentially terrifying.

Other titles have emerged for the painting, including "Two Witches" and "Witchy Brew"; witchcraft is a recurring motif in the Black Paintings, and it is not inconceivable that the painting indeed shows some occult scene rather than a dinner at all.

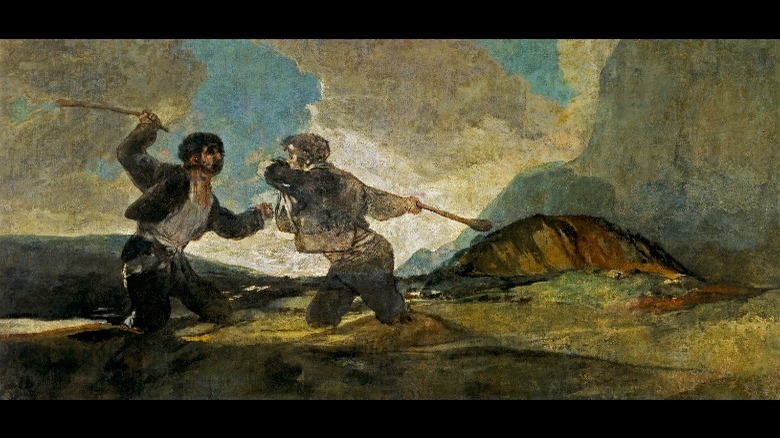

Fight with Cudgels (or The Strangers)

Francisco Goya is famous for his deeply dramatic depictions of military violence, especially those he painted in response to Napoleon's occupation of Spain. Violence is also a theme of his later Black Paintings, most notably in "Fight with Cudgels," a nightmarish wild and rural landscape dominated by two bloodied men battling one another, seemingly to the death.

As noted by Robert Hughes, the two men dressed in traditional peasant attire are sinking knee-deep into the landscape, emphasizing both the finality of their combat and the hopelessness of the scene. The battle is a victorless one, and with the men being of similar age and background, suggests that the painting is a comment on the futility of civil war.

"Fight with Cudgels" appears especially symbolic thanks to the composition, through which the men appear as giants dominating the landscape. In fact, they appear to float above the hills and fields, in the same manner as the three Fates, though an extra layer of detail that has been lost from around the men's legs would likely have given a less ephemeral impression of their battle.

Witches' Sabbath

Francisco Goya's "Witches' Sabbath" is perhaps the work in the Black Paintings series featuring the most overt occult imagery: seemingly a coven of witches, who have received a visitation from an enormous goat-like creature in dark robes. But the work, like other paintings in the series, remains open to numerous interpretations from art scholars who continue to grapple over the deceivingly complex symbolism.

Horrifying in the mania present on the faces of both the assorted witches and the goat-man, "Witches Sabbath" has typically been interpreted as representing a coven's visitation by Satan himself, who is perhaps present at the initiation of a young witch. Just as other Black Paintings seem to offer symbolic critiques of 19th-century Spanish society, it has been argued that this piece similarly suggests that Spain has come under the rule of evil powers.

Other interpretations, such as that of the critic Albert Boime, argue that the painting is doubly subversive, in that the demonic scene may in fact be a critique of the Church itself, whose control over Spanish society was growing in the years that Goya lived at the Villa of the Deaf Man. Biome notes that not all of the witches depicted are enthralled by the creature that holds power over them, while one waits, anticipating judgment.

Women Laughing, and Men Reading

Since the discovery of Francisco Goya's Black Paintings and their transfer to Madrid's Museo del Prado, where they still hang on display today, countless art historians have investigated the positions in which the paintings first hung on the walls of the Villa of the Deaf Man. By doing so, they have sought to elucidate how the paintings inform one another, opening up fresh interpretations of the works in the Black Paintings series.

Two such paintings that benefit from being analyzed comparatively are those titled "Men Reading," sometimes referred to as "Politicians" or simply "The Reading," and "Women Laughing," also known as "Man Mocked by Two Women." The two paintings, which are noticeably alike in terms of their composition, are known to have hung together, suggesting that Goya intended for the two to be experienced in tandem.

One famous interpretation outlined by Fred Licht is that "Women Laughing" also contains a male character, who is either exposing himself or possibly masturbating out of sight of the viewer. If this reading is correct, then, it has been argued, it might be taken as a comment on the actions of the group of men in the painting opposite. Goya suggests that their poring over what may be a political tract or draft law is ultimately self-indulgent, and that they deserve the viewer's ridicule.

Judith and Holofernes

The image of a young woman holding a kitchen knife and backed by the figure of what appears to be an elderly female servant appears at first glance to be one of the less disturbing of the works in Francisco Goya's series of Black Paintings. However, if the Biblical reference of the painting's given title is to be believed, "Judith and Holofernes" is yet another example of Goya turning his attention to scenes of brutal violence.

According to the apocryphal Biblical Book of Judith, the subject of the painting saved her city by seducing the cruel Assyrian general Holofernes, who was laying siege against the city with his army, before decapitating him with a knife. Holofernes' head may be visible in the bottom right corner of the canvas, while the figure in the background is assumed to be Judith's maid turning a blind eye to the murder.

Per Robert Hughes, Goya may have been drawn to the story at the time of the Black Paintings as a suitable subject through which he could express his anti-authoritarian mood following the restoration of King Ferdinand VII.

A Pilgrimage to San Isidro

It may be taken as read that the arc of Francisco Goya's creative life moves from a state of idealistic innocence as a public painter for the Spanish court, to one of disillusionment and psychological self-examination in his later years. And no one piece among the Black Paintings quite demonstrates this as "A Pilgrimage to San Isidro," a dark and twisted landscape showing a throng of menacing-looking pilgrims traveling, if the title is correct, in the direction of a hermitage not far from Goya's home at the "Villa of the Deaf Man."

But the painting was not the only time that Goya represented the pilgrimage in question. In the middle of his career as a public painter, he produced "The Meadow of San Isidro," a romanticized landscape showing the same subject. Fred Licht notes that other early paintings of crowd scenes, such as "The Burial of the Sardine," are generally light-hearted, joyous, or mildly satirical in tone. "A Pilgrimage to San Isidro," therefore, might be interpreted at a mind at the end of its tether, with fear and misanthropy the key emotions the later painting evokes. Another of the Black Paintings, "Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro," shows a similar disdain for religious crowds on the part of the artist.

The Dog

One of the most famous of Francisco Goya's Black Paintings, "The Dog" stands apart from the rest of the works in the series due to its comparatively light color palette, as well as its pushing the boundaries of compositional norms. The head of the subject is the only part of the painting that is wholly identifiable, though it takes up only a minuscule fragment of the canvas.

The painting is famously open to interpretation, as Fred Licht outlines: Is the canine portrayed as heroically ascending a hill, with the viewer's perspective limited by a smaller peak, or hopelessly sinking in what could possibly be quicksand? The meaning of the painting arguably changes according to the mood of the viewer as they experience it. Some critics have identified "The Dog" as Goya's symbolic critique of humanity's hopelessness in the absence of God.

Despite the painting's surface simplicity, "The Dog" continues to mystify people from across the globe, including the painter Joan Miró, who spent half an hour sitting before it on his final visit to Madrid's Museo del Prado, shortly before his death.

Saturn Devouring One of his Sons (or Saturn Devouring his Son)

Undoubtedly the most famous of Francisco Goya's Black Paintings is "Saturn Devouring One of his Sons," a grizzly and horrifying portrayal of the myth of the Roman god who attempted to cannibalize all of his heirs to prevent them from taking his throne from him upon reaching adulthood.

However, there are many mysteries surrounding the painting, not least of which is whether the piece represents the mythical Saturn at all. Fred Licht notes that the painting carries not of the traditional symbols associated with the god that would signify who he is in traditional art, while the look of sheer panic and horror on the cannibal's own face doesn't marry with the calculated nature of Saturn's crimes. Similarly, while Saturn attempted to devour his heirs while they were children, the looming figure's bloodied victim is most certainly an adult, and possibly female.

So who is it? Critics have claimed if it is not in fact Saturn, that the cannibal may represent war or possibly time itself. However, if the creature really is Saturn devouring his son, the painting may have emerged as an expression of Goya's feelings toward his complicated relationship with his own son. Goya had previously painted an unflattering portrait of his son of the same name, suggesting his disappointment in him. "Saturn" may then be Goya processing his own guilt as a result.

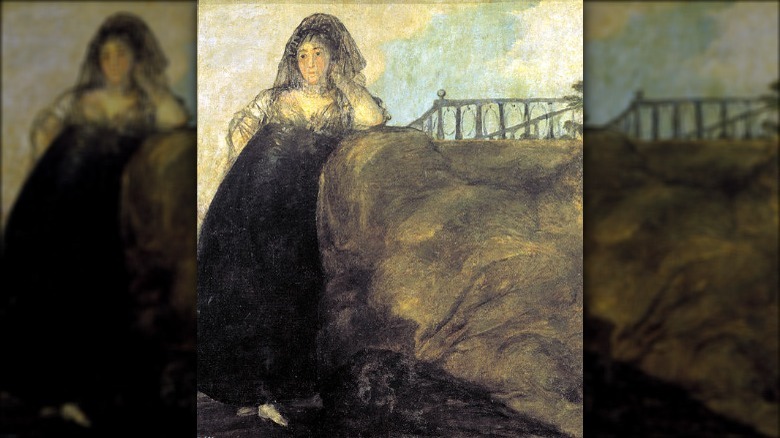

La Leocadia

Also titled "The Seductress," this painting is perhaps the most directly biographical of Francisco Goya's Black Paintings, purportedly being a portrait of his housekeeper, Leocadia Zorilla de Weiss.

Weiss was married to another man, but she and Goya were rumored to have had an affair, despite their 35-year age gap, which may have resulted in the birth of a daughter.

Critics such as Rose-Marie Hagen have noted that, though the woman in the painting strikes a defiant pose, she is dressed in funeral attire and that the rail behind her is certainly of the kind found at a traditional Spanish grave site. This is yet another of the Black Paintings that seems to show the recently-ill artist obsessing over thoughts of his own imminent demise, even while portraying other subjects. In fact, Hagen goes as far as to suggest that while the painting is a portrait of Weiss, it is also a vision of Goya's own grave and of her mourning for him.

Asmodea (or A Fantastic Vision)

"Asmodea," also known as "Fantastic Vision," is typical of the Black Paintings in general in that it appears to be loaded with symbolic potential that can't be definitively pinned down. A landscape in a similar vein to the more famous "Fight with Cudgels," the inclusion of the two enormous but humbly-dressed figures flying through the air above a larger group of traveling civilians — any of whom could be the targets of the armed soldiers firing from the bottom right — suggests a political interpretation.

Various critics such as Evan S. Connell have identified the huge island positioned in the center of the painting as Gibraltar, a place of exile for liberals in Spain during the brutal reign of King Ferdinand VII. If so, "Asmodea" arguably foreshadows Goya's own exile from the country soon after the piece was painted: in 1824 Goya and Leocadia Weiss left Spain forever and moved to France, where the painter died on April 16, 1828, at the age of 82.

Did Goya really create the 'Black Paintings?'

Despite the Black Paintings being considered among the masterpieces of Francisco Goya's impressive oeuvre, some critics have argued that the Black Paintings aren't actually authentic Goyas at all.

One academic in particular, Juan José Junquera, suggests in his 2003 book "The Black Paintings of Goya" that the art originally adorning the walls of the Villa of the Deaf Man was in fact painted by Goya's son or grandson, pointing as evidence to strange wording in the inventory of the Black Paintings taken upon their removal, and mention in the documents of a staircase that was seemingly only added to the property after Goya's death. The motive? Money: with original Goya's lining the walls, the selling price of the Villa of the Deaf Man was considerably higher when the family came to put it on the market than it would have been had the walls been bare.

Despite some press interest in the story, Junquera's theory has never received mainstream attention, and many other academics have dismissed it. As such, the Black Paintings still hang in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, under the name Francisco Goya.