The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Lena Horne

Lena Horne wasn't your average Old Hollywood star. A trailblazer in every sense of the word, the singer and actor made a name for herself during an incredibly problematic time in Tinseltown history. Born in 1917 in Brooklyn, New York, Horne started her professional career at 16, working in the industry for over 60 years. As a Black woman, the "Stormy Weather" crooner fought for equality on the silver screen. She refused to assume stereotypical roles and even became the first Black actor to sign a long-lasting contract with MGM.

In her fight against racial injustice, Horne became a prominent activist. By the end of the 1940s, she was a notable Progressive Citizens of America member, suing various establishments for racial discrimination. Having retired to a more private life by the mid-1990s, the "The Wiz" star died in 2010 at the age of 92.

Though Horne is gone, her legacy still inspires. In November 2022, one of the Broadway theaters in New York was renamed the Lena Horne Theatre in her honor, making her the first Black woman to have a theater there in her namesake. "It's all about legacy, making sure people know that she created a path for others to follow... she had true courage," actor Wendell Pierce said of Horne at the theater's unveiling (via CBS). Of course, the entertainer's rise to the A-list didn't come without difficulty. Let's look at the tragic real-life story of Lena Horne.

Lena Horne's father walked out on the family when she was 3

Lena Horne learned she couldn't depend on her parents from an early age. Horne's father, Edwin Fletcher "Teddy" Horne, was a banker and professional gambler, while her mother, Edna Louise Scottron, was an actor. From the moment Lena was born on June 30, 1917, it was clear that Teddy would become a transient figure in her life. According to the biography "Stormy Weather," Teddy was away gambling "to pay the hospital bill" during Edna's delivery. But Lena scornfully revealed years later that she saw this as her father "pursuing his own interests."

In 1980, Lena divulged to Ebony that her parents separated when she was 3. Teddy simply wasn't ready for marital bliss. In fact, as detailed in "Stormy Weather," he faked sickness to convince his wife he had to travel west. Edna let him go but later told her daughter that he "was too young, too handsome, and too spoiled by the ladies to be ready for marriage." After Teddy disappeared, Edna left soon after, as her dreams of A-list success preceded her desire to be a mother.

With both of her parents gone, Lena's grandparents took her in, and she remained with them until she was 15. Her grandmother, Cora Catherine Calhoun Horne, was a civil rights activist involved with the NAACP. In 1919, Lena joined the NAACP at age 2, with Cora taking her to an office to register.

She got into the entertainment industry to help pay the bills

Lena Horne mainly lived with her grandparents until her grandmother died in 1932. At this point, Horne's mother had remarried and was living in Cuba, so she was taken in by a family friend in Brooklyn, New York, where she attended the Girls High School. During this time, she also took dancing lessons — undoubtedly a skill that would come in handy very soon.

By 1933, Edna Scottron finally returned to the United States with her new beau. The family settled down in Harlem after she took back Horne. Money was tight during the Great Depression, so Scottron got her daughter a job at The Cotton Club as a chorus girl. The white-run Harlem establishment banned Black guests, and the pay was abysmal. Horne made a mere $25 a week, although she performed seven nights a week, three shows per night. The upper-class patrons weren't courteous to the performers, and any affability was reserved strictly for Black celebrities. "The Cotton Club was about flesh," Horne recalled to The New York Times in 1981. "[T]he conditions were really terrible. We couldn't even use the toilet, which was for the customers."

Lena Horne was miserable in her first marriage

By the time Lena Horne was 19, she had met the man who would quickly become her first husband: Louis Jones. According to the star's memoir, "Lena," she met Jones through her father. "I thought he was the nicest thing in the world," Horne recalled, noting that Jones was educated, polite, and the son of a minister.

After dating for three weeks, Jones proposed to Horne — and she said yes. However, as detailed in "Stormy Weather," Horne's mother, Edna Scottron, was furious. An unphased Horne knew that marrying Jones would lessen the grip Scottron had on her, so she went ahead with her plans on January 6, 1937. Sadly, marital bliss ended shortly after as Jones struggled to find stable work. "I thought that he should come home and be warm and loving," Horne recalled in "Stormy Weather," noting that he was also known to be verbally abusive.

Less than a month into their marriage, Horne began to regret her decision to marry Jones due to his abusive nature. Unfortunately, she was also pregnant by this time, and leaving Jones wasn't really an option. Thankfully, in 1940, Horne finally broke ground with her singing career, and by 1944, she was able to divorce Jones.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

Her mother was reportedly incredibly jealous of her

The relationship between Lena Horne and Edna Scottron was never typical. Horne's mother reportedly hoped for a son while pregnant and put her lofty career goals above raising a girl. In contrast, Horne built a stronger bond with her grandmother, who raised her.

Horne must have been shocked when her mom took her back when she was 15. After all, why would she? "She didn't really want the child," Horne's daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, revealed to NPR in 2010. "She just wanted to make her mother-in-law mad." Nevertheless, having Horne around helped the family during the Depression since Scottron secured her daughter a job at The Cotton Club. Sadly, after Horne's first taste of success, Scottron became incensed.

In 1940, Horne began making waves in the entertainment industry – years after Scottron gave up on her dreams. However, Scottron's desire for success turned to jealousy. After Horne appeared in 1938's "The Duke is Tops," her mother scheduled a meeting with her in Los Angeles. There, she asked her daughter to arrange phone calls with producers so she could finally become a star. Upon Horne's refusal, Scottron erupted. If Horne did not cooperate, she threatened to blackmail her by badmouthing her in the press. While Horne never elaborated too much about this debacle, she said in her memoir that she eventually "worked out a solution with a lawyer" and her mother returned to Cuba.

Lena Horne faced racism when performing with the Charlie Barnet Orchestra

Although Lena Horne made her Broadway debut in 1934 after snagging a small role in "Dance with Your Gods," she paused her career after marrying Louis Jones in 1937. However, after they separated in 1940, the budding star decided to give fame another try. Horne joined the Charlie Barnet Orchestra, a predominantly-white swing band. While this offered the singer the chance to record on the group's label, Bluebird Records, time spent on the road proved to be a struggle.

Touring with the Charlie Barnet Orchestra was far from a comfortable experience. After singing at various venues, Horne was forbidden to stay and socialize with the audience and other band members. The hotels were also segregated, so Horne slept on the tour bus until Barnet told his manager something had to change. "Our band manager would go to the [hotel] desk, order the rooms, jabber to Lena in Spanish double-talk," Barnet recalled in "Cafe Society: The Wrong Place for the Right People." "Then he'd tell the desk clerk, 'Our Cuban singer would like a single room and a bath.'"

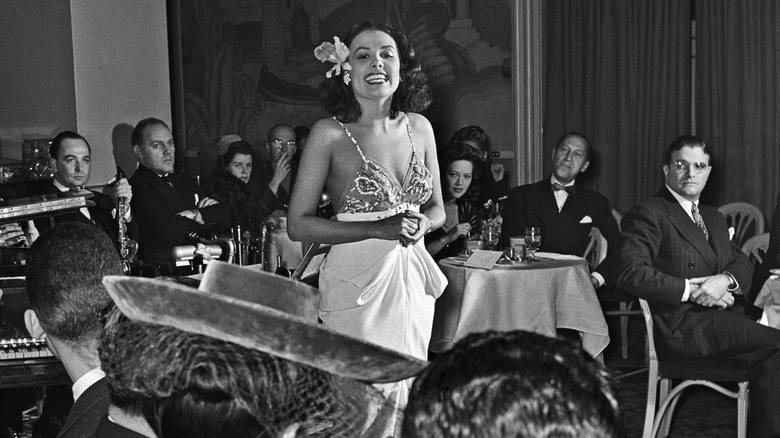

Despite Barnet's temporary solution, Horne was sick of racial discrimination. After a few months, she left the band and returned to New York, where she landed a gig at the first racially integrated club in the city, Café Society Downtown.

Lena Horne's success at MGM angered other Black actors

Lena Horne's reputation finally grew in the 1940s. According to "Icons of Black America," she moved to Hollywood in late 1941 and rubbed elbows with the industry's finest. Additionally, she dated high-profile entertainers like Orson Welles and Artie Shaw. She soon released her debut album, "Moanin' Low," but it was not the only milestone she would reach.

At this time, MGM owner Louis B. Mayer had been pressured by organizations such as the NAACP to give Black actors more varied film roles. Walter White, the NAACP's executive secretary, got Horne a meeting with Mayer. What came out of the 1942 meeting was historical: an offer for a seven-year, high-paying contract. Horne took the deal, making her the first Black performer to land such a deal with one of the big studios, and the highest-paid Black actor in Old Hollywood.

Horne's refusal to play stereotypical roles wasn't without controversy. In the PBS special, "How It Feels to Be Free," professor of cinema studies Jacqueline Najuma Stewart explained that Horne's contract made fellow Black stars irritated at the prospect of losing out on roles. In Horne's words: "My signing this contract and their hearing that I would not do certain kind of work, got me into a lot of trouble with Black actors." Later, she added, "[The] very fact that I was one of the first, you know, I was isolated right away because there was no niche for me."

She was accused of trying to pass as a white woman in Hollywood

Lena Horne's long-term contract with MGM was undoubtedly an achievement, but frustration and loneliness soon followed. According to the PBS documentary, "How It Feels to Be Free," audiences began asking questions when they first saw her on screen. "Is she Black or is she white?" was a common one. When Horne filmed her first movie with MGM, 1942's "Panama Hattie," the studio asked her to "pass as Latin." As Horne heartbreakingly recalled in the documentary, "[W]hen my own people accused me of trying to pass, I was furious, and I felt more isolated than ever."

Unfortunately, this wasn't the only situation that left Horne feeling defeated. As detailed in "Icons of Black America," MGM believed Horne's skin tone should be darker when filmed on camera, so they hired a makeup artist to create a foundation that darkened Horne's skin to match her co-stars called "Light Egyptian."

A few years later, when shooting for the 1951 film, "Show Boat," began, Horne was vying for the lead role of Julie. This character was described as having the same lighter skin tone as Horne, so why wouldn't she get the part? According to "How It Feels to Be Free," MGM chose the star's close friend, Ava Gardner, as they felt it was too risky to give a Black woman the starring role. Ironically, as Horne revealed, "they put dark make-up on her, created for me especially."

Lena Horne only had two speaking roles as an actor at MGM

Although MGM employed Lena Horne, her refusal to play stereotypical Black roles was met with resistance. Throughout her time with the studio, Horne found work in other films and various musicals. That said, the only two movies where she was actually able to have speaking roles were "Cabin in the Sky" and "Stormy Weather," as detailed in "How It Feels to Be Free." Instead, she was mainly cast as a singer. The star later explained, "They hadn't made me a maid, but they hadn't made me into anything else either."

This lack of meatier roles was due to the fact that MGM was trying not to offend audiences in the South. "Icons of Black America" notes that Horne was relegated to singing parts so these scenes could be cut before playing in certain theaters. "She could never be in anything that furthered the plot or was a crucial moment in the movie," Horne's daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, told NPR.

The actor's most groundbreaking role was set to be in the first all-Black musical since 1929, "Cabin in the Sky." In the movie, Horne had a now-infamous scene where she was in a bubble bath. Dubbing it one of the most beautiful moments in the film, Horne sadly recalled (via "How It Feels to Be Free"), "They cut it out because everybody said, 'What's this Black woman doing in these soap suds acting like, you know.'"

She was forced to go back to nightclub performances

Having realized that MGM would never offer her a leading role, Lena Horne focused on her nightclub singing career. In 2010, her daughter revealed to NPR that Horne headlined shows in America and Europe — but even this professional shift wasn't without hardships.

"She couldn't really advance in Hollywood because she became more increasingly associated with the Left," explained American historian Ruth Feldstein in the PBS documentary. Sure enough, along with her near-lifetime association with the NAACP, Horne also became friends with leaders such as Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Dubois. Suspected to be a Communist sympathizer, Horne's name was published in the right-wing journal, Red Channels. She was effectively blacklisted from Hollywood — and couldn't make a film for the next six years.

At the time, many people racistly associated all Black Americans with communism. As Gail Lumet Buckley wrote in her biography, "The Hornes: An American Family," her mother was wholly aware that communism and the civil causes she advocated for were linked — but that wasn't a problem. "She felt that most of those causes needed all of the help they could get," Buckley explained. In any case, Horne had to get off this list to maintain her career. So, she wrote to a union and met with right-wing columnist George Sokolsky, who cleared her name. But Horne stood her ground, declaring that, while she'd steer clear of Communist organizations, she would continue speaking out about racial injustices.

The road to Lena Horne's second marriage was rocky

Lena Horne eventually found love again after divorcing Louis Jones. After signing her contract with MGM, she met Lennie Hayton, a composer at the studio. The pair crossed paths at MGM and various events, but it wasn't until Horne finished shooting 1943's "Stormy Weather" that sparks flew. "I can hardly claim that ours was love at first sight," Horne later wrote in her memoir, "Lena."

Horne wrote of problems early in their relationship. To avoid disturbing her children, she evaded bringing her new flame home. Another problem was that the composer was white, and interracial relationships still caused heads to turn in Hollywood. As Horne explained, her mental health was in tatters during this time, and suddenly living in the public eye while going through a divorce and raising children was challenging. Thankfully, Hayton stood by her, offering whatever support he could.

A gleeful Horne accepted Hayton's proposal four years later. The catch? Due to state and federal laws prohibiting interracial marriage, the couple had to go abroad. At the city hall in Paris, France, Horne and Hayton married in December 1947. Some members of Horne's family stopped speaking to her after hearing she had married a white man. Interestingly, Horne revealed to Ebony years later that she initially began dating Hayton to boost her career. That said, she grew to love him. "It turned out to be a perfect marriage," she said.

In a 13-month timespan, she lost her husband, her son, and her father

Lena Horne remained busy in the later years of her career, and in the 1960s, she pivoted to becoming even more active in civil rights movements across the country. Sadly, Horne suffered three devastating blows at the start of the new decade: Her father, Edwin Fletcher "Teddy" Horne, and son, Edwin Jones, died in 1970. A year later, she lost her husband of almost 25 years, Lennie Hayton. Her husband died suddenly from a heart attack, and her 30-year-old son developed kidney disease.

"At first, of course, I thought that this is it. This is the end of me," Horne recalled to Ebony nine years later. After some reflection, Horne concluded that losing the three most influential men in her life made her stronger. For four years, her father and son knew their time on this planet was ending. "Their dying speeded up my training," she poignantly added.

After her tragedy, Horne retreated from the public eye, preferring to live a reclusive life. By the mid-1970s, however, Horne made her return, appearing on Broadway with Tony Bennett in 1974, and then starring in "The Wiz" four years later. She returned to Broadway to star in an autobiographical show in 1981, which won her a Tony. Long-term, Horne told Ebony that losing the three men benefited her career. "Professionally, the pain really opened me up to my audience. From then on, I was as one with my audience."