The Treasure Of Nimrud: The Ancient Assyrian Riches Unveiled

The city of Nimrud is one of the most important archaeological sites in the Middle East. The palace complex discovered there was once the beating heart of the ancient Assyrian Empire, a mighty civilization that once dominated the region for a time. Precious ivories and monumental statuary found at the palace are a dazzling testament to the power and sophistication of Assyrian society.

The hundreds of gold objects found at Nimrud in the 1980s are some of the most breathtaking ever discovered, rivaling some of history's most important archaeological finds. Despite the gold's great value and importance, few people have heard of Nimrud or its treasures. The mountain of riches discovered under the palace has spent most of its life hidden away, its location known only to a precious few people.

Unfortunately, the history of the archaeological site at Nimrud is tied up with the difficult history of modern Iraq. After a lengthy search to find the treasure, the city was ravaged during the Iraq war, and eventually flattened by the Islamic State. Only very recently have researchers returned to the ruined city, eager to search for more wonders hidden beneath the earth.

What's so special about Nimrud?

The ancient city of Nimrud in Iraq was an important Assyrian city during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the heyday of the Iron Age superpower. At this time, Assyria enveloped its neighbors in the Levant and Egypt, and they used their newfound wealth to build huge palaces and beautiful cities. During the 9th century B.C., at the height of this glorious epoch, King Ashurbanipal II transformed Nimrud into Assyria's new capital, according to World History. However, its roots go back far earlier than this; Nimrud (or Caleh) is mentioned as an important city in the Hebrew Bible, and the earliest known settlement in the region dates back as far as 6000 B.C.

The bloodthirsty Assyrians were known for their total ruthlessness on the battlefield, but also for their great libraries and monuments. During the empire's golden years, the city of Nimrud became a cultural powerhouse — adorned with magnificent sprawling palaces, a zoo, botanical gardens, temples, and a towering ziggurat that stood for thousands of years. It also became the traditional resting place of Assyrian queens, whose tombs were filled with stacks of elaborate treasures.

Sadly, Nimrud's fortunes waned with the fortunes of the empire itself — the city ceased to be the capital in 706 B.C., and it was torched in 612 B.C. by a coalition of Assyria's many enemies. Nimrud became just another biblical legend, the ruins disappearing from view until the 19th century.

Finding the biblical city

During the 19th century, archaeologists from Europe took a great interest in the ancient Near East. European officials on assignment in Ottoman territories began scouring the landscape for sites they'd heard of during their costly educations. Among them was Henry Austen Layard, according to AramcoWorld, the British vice-consul in Mosul who rediscovered Nimrud in 1845.

A history aficionado, Layard noticed the Nimrud Ziggurat (by then just a mound) jutting out of the landscape, and he proceeded to investigate. Working with local guide Hormuzd Rassam (a man who can arguably claim the title of Iraq's first archaeologist), the pair uncovered the spectacular palace of Ashurbanipal at Nimrud, the first of many investigations into the site. Although Layard and Hassam did not find the treasure that Nimrud is now famous for – they did not realize what city they had discovered, according to World History – they did find a series of gigantic Assyrian relief sculptures as well as an enormous obelisk.

The importance of the site was confirmed in the 1850s, when an astounding set of ivory carvings were uncovered at Nimrud by another archaeologist. These detailed ivories were once gilded in gold and set with precious gems, and although they had lost much of their sheen, they still look spectacular today. Many more ivories would show up at the site in the mid-20th century, unearthed by the husband of famous crime writer Agatha Christie, and wiped clean by Christie herself. However, while the ivories would become world-famous, none of them compared to the so-called "Nimrud treasure," which was not discovered until 1988.

The treasure is revealed

In the '80s, when Iraq came under the control of Saddam Hussein, a team of archaeologists working on the palace of Nimrud made an amazing discovery that dazzled the world: A series of magnificent royal tombs, filled with hundreds of exquisitely made solid gold objects.

As described in Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein's book "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs," it turned out that the team that excavated much of the Nimrud palace complex in the 1950s had failed to look under the floor, where the treasure was located. Underneath the palace were four magnificent royal tombs, hidden away for centuries from passing looters. The first tomb was found in the spring of 1988, and the fourth and final one (thus far) was found in 1990.

Under Hussein's rule, news about the treasure was very slow to filter out to the rest of the world, and the secretive regime did not allow the press to reveal much about the finds to outsiders. In 1989, access to the treasure was finally granted to Time, and the publication ran a major story on the tombs and their treasures. However, by 1991, the treasure had already been locked away, hidden in a bank vault at the beginning of the Gulf War.

What was found at the site?

An investigation into the hidden tombs under Nimrud's palace revealed a hoard of gold objects studded with precious gems. Many of these items display a quite stunning level of craftsmanship even by today's standards, and the treasure was found to be so unbelievably valuable that it was declared completely uninsurable, per NPR. Among the finds stashed in the tombs were solid gold earrings and necklaces, a flask made entirely of solid crystal, and glittering gold rosettes made to look like flowers.

According to the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, many of the objects were found nestled around a set of bodies, which had been interred together under the palace in bronze, stone, and clay coffins. One of the women found at the site has been identified as Queen Hama, who was found wearing a particularly magnificent crown decorated with solid gold leaves, fruits, and winged genies. Another two bodies were found buried together with a gold tiara, one of which was easily identified as Queen Yaba. Inscriptions left in the tombs, as well as solid gold seals, helped researchers narrow down the identities of at least some of the royal women, such as those found in Tomb III, where a note was left that clarified one of the bodies belonged to Queen Mullissu-Mu-Kannishat-Ninua, wife of Ashurbanipal II, according to Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein's "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs."

In addition to the jewelry, archaeologists found some more unusual items, such as small figurines and cosmetics. In Tomb I, for example, a woman's body was recovered, surrounded by tiny erotic statues depicting a series of sex scenes.

Yaba's Curse

One of the more surprising discoveries to come from the Nimrud tombs was a series of curse tablets. Much like Pharaohs' tombs in Egypt, the royal resting place of Queen Yaba was guarded with magic that promised woe to thieves or anybody else looking to disturb the queen's rest, according to World Archeology. Also, as in ancient Egypt, archaeologists found evidence that these warnings were ignored: A second body was placed in the tomb some years later, despite a general prohibition against it.

Yaba's curse, which is inscribed in marble in tomb II (per Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein's "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs"), reads: "Whoever in time to come, whether a queen who sits on the throne, or a lady of the palace who is a favorite concubine of the king, removes me from my tomb, or place anyone else with me, or lays hand on my jewelry with evil intent, or breaks open the seal of this tomb, let his spirit wander in thirst in the open countryside."

Tomb III, the final resting place of the wife of Ashurbanipal II, Mullissu-Mu-Kannishat-Ninua, also came with a curse. It states: "whoever removes the sarcophagus from its place, his spirit will not receive funerary offerings with (other spirits) ..."

War breaks out

The fate of the treasure of Nimrud caused many archaeologists and historians great anxiety in the years that followed the 1988-90 excavations. After a brief exhibition of the treasures in the Iraqi National Museum, the loot was hidden away in a bank vault in 1991, at the start of the Gulf War. The bank was subsequently bombed during the conflict, according to Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein's "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs," and although the violence did no damage to the gold, information about the enormously valuable loot became increasingly scarce. Rumors spread that Saddam Hussein had given some of the jewelry to his lover as a gift, and as tensions with the west escalated, academics from the U.K. sent to get a rare glimpse of the treasure were blocked from entering Iraq.

War broke out again in 2003, when the U.S. moved to remove Hussein from power. Across the country, widespread looting followed, and the bank was bombed a second time. An art-theft crisis ensued, as various treasures, including the priceless Warka Vase housed in the Baghdad Museum, were stolen by opportunists during the chaos that dislodged Hussein.

The lion of Nimrud, one of the most famous ivories from the ancient city, was carried away from the museum, sparking international outrage. The American soldiers occupying Baghdad watched the looters with indifference, preoccupied with the political situation in Iraq.

The rediscovery of the treasure

In the summer of 2003, the treasure of Nimrud was rediscovered in the Iraqi Central Bank. The bank had been badly bombed, but although parts of it were reduced to rubble, the vault was left unscathed. It transpired that people had tried to steal the treasure, but with no success. As Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein's "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs" describes, one unfortunate looter shot at the door with a grenade launcher from just 10 feet away and was killed in the ensuing blast, having barely dented the vault. The bodies of various other looters were also scattered around the bank, including men who had shot at the door in an attempt to break in but who were ultimately killed in the chaos.

The damage done to the vault by the grenade launcher burst a pipe and caused severe flooding to the basement — 15 meters of water that had to be pumped away before the treasure was finally recovered. Some of the more delicate items suffered water damage, but for the most part, the collection was unscathed. On a mission to protect Iraq's history, Jason Williams, a British anthropologist, teamed up with National Geographic and an American Marine Colonel to save the gold in an archaeological rescue operation, per The Wall Street Journal.

Although they were successful, due to continuing instability in Iraq, the treasure went on display for a single day before they were hidden again for safety reasons. Reuters reported in 2008 that the gold was still locked away in the Iraqi National Museum for safekeeping, five years after the war.

Some of the Nimrud treasure may have been stolen

Although 613 pieces from the treasure of Nimrud were recovered in the aftermath of the Iraq War, it is not clear whether the boxes that were found in the Iraqi Central Bank represent a complete set. In 2008, a pair of extravagant gold earrings went up for auction a Christie's valued at $65,000. Iraqi authorities recognized the style of the earrings and intervened in the auction, claiming they may have come from one of the Nimrud tombs. The pieces are believed to have been stolen in the 1990s, and were seized before the auction could begin.

The lead archaeologist who worked on the dig in the 1980s, Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, stated in his book "Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs" that some of the treasure was never stored in the Central Bank at all. Non-gold items were housed in the Mosul Museum nearby, which was inevitably looted. Many items from the dig may still be out there somewhere, floating around in the art market.

The Islamic State destroys Nimrud

While the treasure of Nimrud survived the Iraq war, the city of Nimrud did not survive the turbulent years that followed. With the dramatic appearance of the Islamic State in Iraq, the remains of many ancient sites across the country suddenly became ideological targets.

On a mission to destroy pre-Islamic "idols," Islamic State fighters smashed up the nearby museum in Mosul with sledgehammers. They stole pricey works of art and destroyed as much sculpture as they could. Eventually, the Islamic State declared that they had made Nimrud one of their historical targets. A policeman posted to guard the site was beaten to a pulp by the fighters, and later watched as the city was smashed to bits. While thankfully two great winged bulls from the palace were safely deposited thousands of miles away in the British Museum, the rest of the city was not so lucky. Islamic State fighters gleefully destroyed many of the city's ancient wonders with hammers and bulldozers — and they filmed themselves while doing it. The outside of Nimrud palace was defaced, and the city's walls were flattened.

One of the saddest losses was the ancient ziggurat, which was never properly investigated by archaeologists before it was wiped off the map. Its once towering mass was reduced to the size of a small mound by the Islamic State. Although the Islamic State fighters were driven away in 2016, the site was left abandoned for a time, and local archaeologists believe that valuable bits of the site may have been stolen in the interim before archaeologists returned.

The Nimrud Rescue Project

After Islamic State fighters left the city of Nimrud in November 2016, it took some time for archaeologists to return again. At first, the site was monitored from a safe distance using drone technology. Authorities feared that Islamic State fighters may have laid traps or bombs in the area, especially given that they were still camped out in nearby Mosul at the time. From the air, the widespread destruction of the city could be seen quite clearly, and UNESCO declared that the Islamic State's destruction of the site was a war crime.

In the spring of 2017, an international plan to save and rebuild the ancient city was proposed. The Nimrud Rescue Project offered Iraqi archaeologists the opportunity to learn the necessary skills to restore and catalog the rubble-strewn site, and reverse some of the damage. The U.S. State Department, in conjunction with the Smithsonian Institute, offered up $400,000 to help aid in the reconstruction, teaming up with the local Iraqi antiquities department. Chips from smashed-up ancient friezes were collected together, and the area was fenced off in order to begin the painstaking process of rebuilding the palace and the city, piece by piece.

New finds emerge from Nimrud in 2022

Today the future looks a lot brighter for Nimrud, and research work on the palace has resumed. In 2020, artist Michael Rakowitz was commissioned by the New York Wellin Museum to help archaeologists reconstruct what the palace may have looked like in ancient times. The goal is to one day reconstruct the entire palace in its original vivid colors, including the areas destroyed by the Islamic State.

Meanwhile, in Iraq, archaeologists have returned to the site of Nimrud to excavate once again. Despite the damage done by decades of war and looting, the city still rewards tenacious archaeologists, and sites such as the fascinating temple of Ishtar, are now being restored.

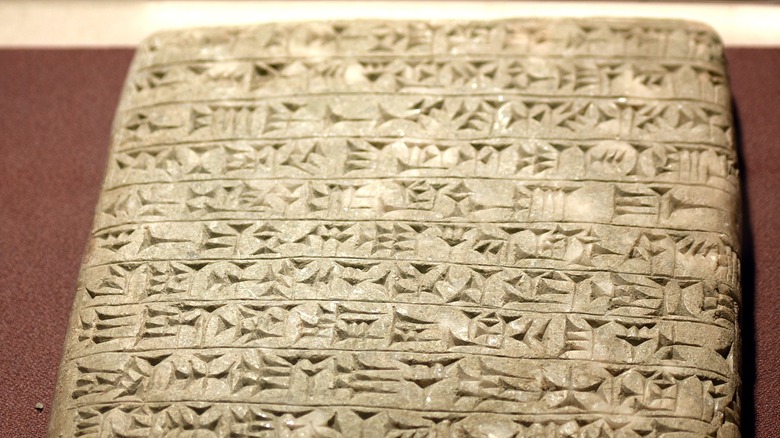

The palace at Nimrud has never been fully excavated, raising hopes that a large part of the complex has remained safely untouched under the sand. In 2022, the threshold of a doorway, inscribed with a cuneiform inscription, was discovered by a new team of archaeologists, part of the first major dig in the city since it was occupied by Islamic State fighters.