Red Flags That Signaled The Beginning Of The End Of These Classic Rock Bands

Sometimes, you just know the end is nigh for your favorite band. You may be reading rumors about one member not getting along with someone else in the group, and they may or may not be siblings. Or perhaps the entire band has allegedly had it with the dictatorial leader. There may be one disturbing report or another about a member's substance abuse problems. Or the entire band might be crumbling underneath the weight of pressure to follow up a big hit ... or had just followed up that big hit with a colossal flop.

There are so many reasons why a great band decides to break up, but behind those reasons are red flags or portents like the ones mentioned above. With that in mind, let's look at a number of classic rock bands (i.e. bands who mainly enjoyed success between the '60s and '90s) and the warning signs that came before their eventual disbandment. For all these legendary acts, the writing was on the wall in the months (or in some cases, a few years) leading to their breakup.

Nirvana

As of early 1994, Nirvana had released three studio albums, with the second one, "Nevermind," kickstarting the grunge revolution, and the third one, "In Utero," also topping the album charts following its 1993 release. The Seattle-based power trio was still comfortably on top of the rock scene, but an incident on March 5, 1994, involving singer-guitarist Kurt Cobain served as an eerie harbinger of things to come.

As reported by Rolling Stone, Cobain was found unconscious in his Rome hotel room on that morning, and it was later revealed that the frontman had consumed about 50 Rohypnol tablets. Cobain remained in a coma for 20 hours as he received treatment at two hospitals, and while he recovered successfully, it has been alleged that he left a suicide note at the scene of his overdose. Multiple sources, including Nirvana's management group, Gold Mountain Entertainment, denied this claim, but the Cobain biography "Heavier Than Heaven" by Charles R. Cross quoted several passages from the purported suicide note, where the singer expressed how tired he was of touring and how he felt his wife, Courtney Love, no longer loved him.

Exactly one month later, Cobain died by suicide, and that also marked the end of Nirvana and their brief, yet groundbreaking run as a band.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Yardbirds

You may know the Yardbirds as the band that jumpstarted the careers of three iconic lead guitarists — Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page. Clapton's exit didn't keep the Yardbirds' train from a-rollin', as he was replaced by Beck in 1965, and when it was Beck's turn to depart more than a year later, Page (who originally joined on bass) took over on lead guitar.

Ultimately, it wasn't frequent lineup changes that stalled the Yardbirds' momentum, but rather their 1967 album, "Little Games." Thanks to Page's innovative playing style, the band was transitioning to longer, more experimental songs, including a version of Jake Holmes' "Dazed and Confused" that sounds very similar to the Led Zeppelin version, albeit with Keith Relf's calm baritone in place of Robert Plant's manic, high-pitched wailing delivery. But "Little Games" offered little of that experimentation, as producer Mickie Most seemingly pushed for a poppier, more commercial direction. "You have no idea how quickly that was recorded," Page told Reverb in 2020. "Right, red light's on, take — next! Mickie Most didn't like albums, he only liked singles." Unfortunately, none of the singles from "Little Games" did much on the charts, with the title track peaking at No. 51 on the Billboard Hot 100.

The Yardbirds pushed forward until the summer of 1968, when vocalist Relf and drummer Jim McCarty announced they were leaving the band.

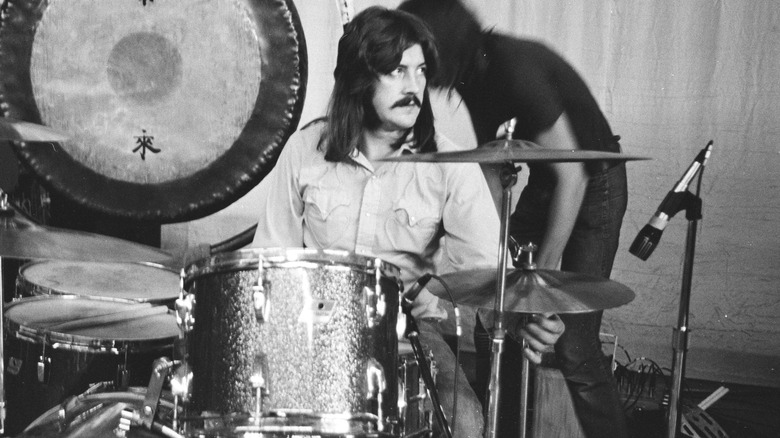

Led Zeppelin

After briefly performing as the New Yardbirds, Jimmy Page's new band became known as Led Zeppelin, and they enjoyed a productive run that ended in 1980 with John Bonham's death. Mere months before that, the drummer notably collapsed during a tour date at Nuremberg, Germany. At that point, the band had only performed three songs, and Plant had just introduced "In the Evening," a song from their 1979 album "In Through the Out Door." As heard in a clip from the concert, there is a long period of silence before Plant asks the audience to be patient due to a "slight technical problem." That problem was anything but technical, and Bonham's collapse ended the show prematurely.

As claimed by the band's tour manager Richard Cole in Mick Wall's Led Zeppelin biography "When Giants Walked the Earth," Bonham was doing heroin ahead of the tour. While Wall theorized that "Bonzo" might have been going through withdrawal when he collapsed, Robert Plant told the author a totally different story. "I know he had to eat 50 bananas immediately. He had no potassium in him," the frontman said, adding that nobody in the band paid much attention to medical concerns when they were touring.

On July 7, the band played what would turn out to be their last ever concert, and on September 25, Bonham died at the age of 32 after choking on his own vomit while asleep; according to the coroner's report, the drummer consumed 40 shots of vodka in a span of 12 hours.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

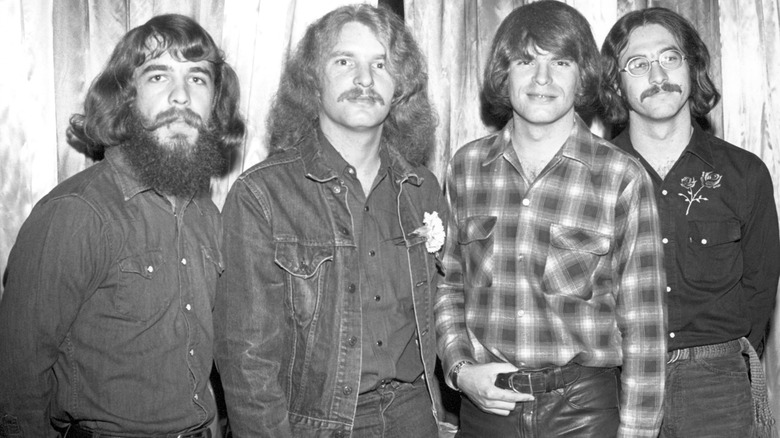

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Being the oldest member of Creedence Clearwater Revival, Tom Fogerty was the band's leader when they were known as the Blue Velvets, and later the Golliwogs. As the group evolved their sound into the signature swamp rock that made them superstars in the late '60s, he ceded leadership to his younger brother, John Fogerty. But as the hits kept coming, John's grip on CCR grew tighter and tighter, and by the early '70s, Tom and his other bandmates, bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford, were reaching their breaking point. After being talked out of it multiple times, Tom Fogerty finally quit CCR in 1971. Apparently, Tom wanted to contribute some lead vocals and flex more of his creative muscle on their album "Pendulum," but his little brother wasn't willing to budge.

Creedence Clearwater Revival continued as a three-piece with John Fogerty, Cook, and Clifford. The trio recorded one final album, "Mardi Gras," in 1972, and while each member was given a chance to contribute equally as singers and songwriters, Rolling Stone gave it a savage review, accusing John Fogerty of exposing his bandmates' perceived mediocrity by allowing them to write and sing on their own songs. Cook's compositions were particularly roasted, as the outlet's Jon Landau wrote that his songs were "bad enough to qualify as offensive." Ouch.

Following the critical disappointment that was "Mardi Gras," CCR announced their breakup on October 16, 1972.

The Clash

They were the "only band that matters" ... until they didn't. The Clash disbanded in 1986 as a shadow of their hard-hitting old selves, and while it's easy to blame their poorly received final album, 1985's "Cut the Crap," for their breakup, the lineup changes that preceded the album were arguably bigger red flags for the punk icons.

Although nowhere as visible as frontman Joe Strummer or guitarist Mick Jones, drummer Topper Headon was an integral part of the Clash's classic lineup, and his 1982 firing due to his heroin use was a huge setback for the band. In fact, Uncut referred to his sacking as the "beginning of the end" of the Clash, and Strummer still felt bad about the decision when he spoke to the outlet for its September 1999 issue. Jones was the next member of the classic lineup to go, as he was fired in September 1983 because he had "strayed from the original idea of The Clash," per a press release. Strummer told Uncut that he felt responsible for the firings as he had allowed manager Bernie Rhodes to take too much control over the band. Which, not surprisingly, included mixing "Cut the Crap" in a manner that Uncut called "atrocious."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Pixies

One would think that Pixies should have been so much bigger than they were and more than just a band that influenced countless alternative rockers through their classic late '80s and early '90s albums. Theoretically, their big break could have come when they were chosen to open for U2 during their 1992 tour, but as guitarist Joey Santiago revealed to Spin in 2004, he was the only one who was excited to open for one of the biggest rock bands in the world; apparently, frontman Black Francis and bassist Kim Deal were less than thrilled to be U2's opening act.

"That was probably the biggest tour we opened," drummer David Lovering told Spin. "It was also the only tour where no one knew who we were." In that same feature, Francis hinted at the inter-band turmoil that was brewing during that "boring" tour. "Nothing against U2, but an opening slot is thankless," the frontman said. "We were not getting much of a reaction and feeling a little tense, especially me. I needed to get away from that band and those people."

According to Deal, Francis told her in April 1992, not long after their stint on the U2 tour, that he wanted Pixies to "take a sabbatical." In January 1993, Pixies was officially done, though, at the time of the Spin feature, it was still heavily debated whether Francis, as he claimed, really announced the breakup to his bandmates via fax (save for Santiago, whom he called). Either way, it would seem that he didn't tell anybody in person about the difficult news.

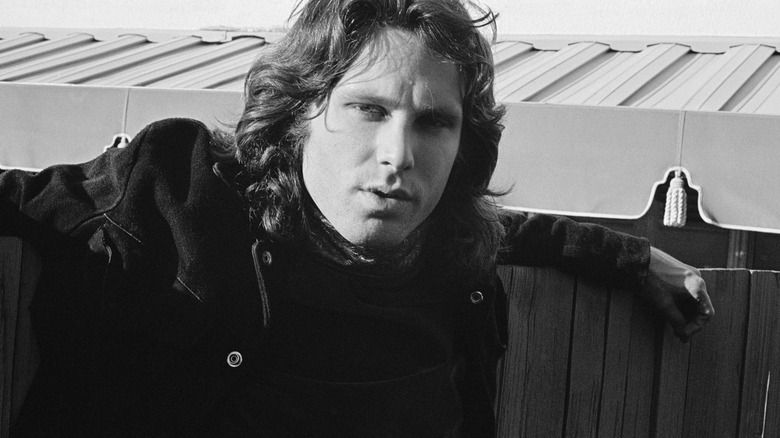

The Doors

No, the Doors did not break up right after frontman Jim Morrison's death. But it was Morrison's tragic passing on July 3, 1971, that was, by far, the biggest blow to a band that had two No. 1 singles in the late '60s and was still very relevant at the dawn of the following decade. Without their charismatic, oftentimes controversial lead singer, the Doors had some giant-sized shoes to fill ...

... so they decided to fill those shoes themselves. Keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger, and drummer John Densmore decided to push forward with the album they were recording at the time of Morrison's death, which was aptly titled "Other Voices" and released in October 1971. Although all three men were talented musicians at their respective instruments, it just wasn't the same without the Lizard King, and contemporary reviews of the album have said as much. Manzarek and Krieger both shared lead vocals on "Other Voices," but neither of them could measure up to the lofty standards set by Morrison.

The Doors released a second post-Morrison studio album, "Full Circle," in the summer of 1972, but much like its predecessor, it didn't garner as much attention from the public as the Morrison-era albums did. On August 30, 1973, the Doors wisely decided to call it a day ... until they briefly reunited in 1978 to record "An American Prayer," which consisted of Manzarek, Krieger, and Densmore playing over Morrison's spoken-word poetry recordings.

Deep Purple

By 1975, Deep Purple had already survived a few significant lineup shakeups — singer Rod Evans and bassist Nick Simper were replaced by Ian Gillan and Roger Glover, who were later replaced by David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes. But when guitarist Ritchie Blackmore left the band that year to team up with a little-known singer named Ronnie James Dio and form a new group called Rainbow, one had to wonder how much Deep Purple had left to offer with what would become their "Mk. IV" lineup.

Blackmore's replacement, Tommy Bolin, was a similarly talented individual who recorded two albums with the James Gang and had played with jazz fusion legend Billy Cobham. However, his debut album with the group, the R&B and funk-tinged "Come Taste the Band," peaked at an unremarkable No. 43. Worse, Bolin and Hughes were using a lot of drugs as they toured behind the album, and by March 1976, Coverdale had seen enough, walking out after a disastrous show in Liverpool and effectively quitting Deep Purple.

Four months later, Deep Purple officially announced their breakup, and on December 4, 1976, Bolin died of a drug overdose at the age of 25. Deep Purple would reunite in 1984, with Blackmore quitting for a second — and final — time in 1993.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Oasis

It was logical to think Oasis would keep on playing indefinitely, considering how long they'd lasted despite the band's central figures, brothers Liam and Noel Gallagher, having practically been at each other's throats from day one. As such, it came as a bit of a surprise when it was all over toward the end of the summer of 2009.

At first, it didn't seem that out of the ordinary when Oasis announced on August 23 that they would be canceling their scheduled performance at the Chelmsford, England, leg of the V Festival. According to the band, Liam had come down with a case of viral laryngitis. Noel wasn't feeling well either, as he blogged about having a bad stomachache after the previous night's Staffordshire leg. Five days later, though, the brothers got into a violent argument backstage as they were preparing to play a show in Paris, with Noel throwing a plum at Liam, and Liam retaliating by attempting to bash his big brother with a guitar.

The day after, on August 29, Noel issued a statement (via the BBC), announcing he had just quit the band. "People will write and say what they like, but I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer," he said. As reported by The Guardian, Liam sued Noel in 2011 for claiming in a BBC interview that the real reason behind the V Festival cancellation was that Liam was too hung over to play. Oh, if only the Gallagher boys could do as their song says and not look back in anger.

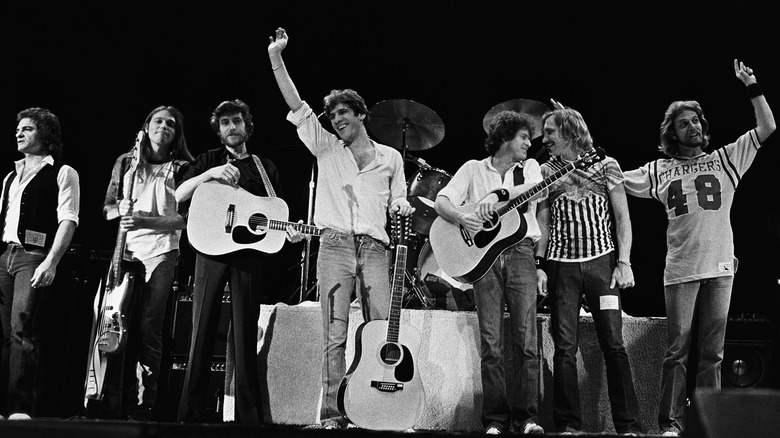

The Eagles

The Eagles were undeniably flying high after the release of their 1976 magnum opus "Hotel California" — both the album and its title track. So how do you top a banger of an album and keep that positive momentum going? That was actually the quandary the Eagles faced as they spent 18 months recording what would become "The Long Run." And while singer-drummer Don Henley said in a 1977 interview (via Ultimate Classic Rock) that he wanted to be like the Beatles in the sense that deadlines and pressure made them as prolific as they were, the exact opposite happened. "There was so much pressure that Don and I didn't have time to enjoy our friendship," singer-guitarist Glenn Frey recalled separately. "We always had to worry about doing this or living up to that."

Instead of being a double album as originally planned, "The Long Run" featured only 10 songs when it finally arrived in September 1979. Through it all, the stress took its toll on the Eagles, and it didn't help that the record got middling reviews following its release.

All that stress led to band dysfunction, and that dysfunction was on full display during a 1980 benefit concert for California Senator Alan Cranston, which saw guitarist Don Felder and Frey exchanging threats onstage. Days later, Eagles producer Bill Szymczyk informed Felder that "there is no band at this time," and it would take another 14 years before the group would reunite and make new music once again.

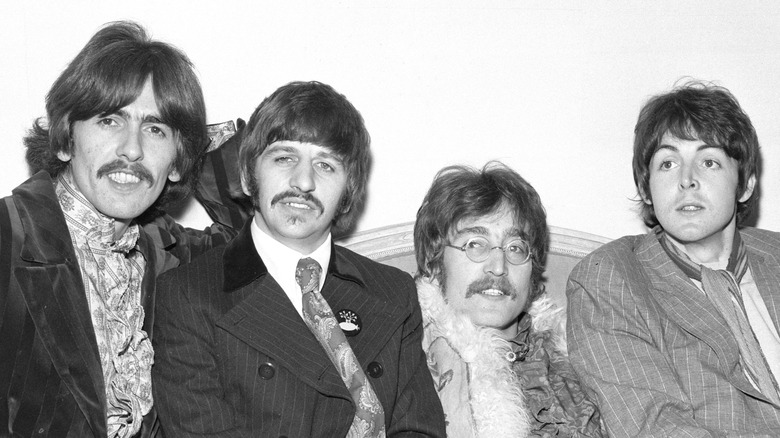

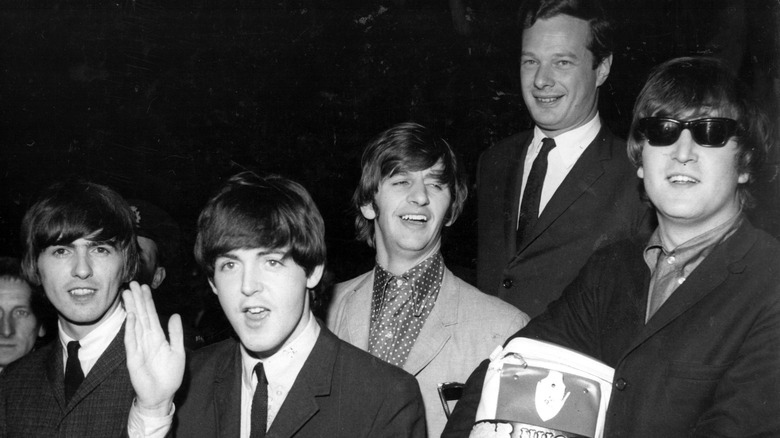

The Beatles

While there are still plenty of card-carrying members of the "Yoko Ono broke up the Beatles" camp, in the years since it's become clear that John Lennon's relationship with — and later marriage to — his second wife should not be considered a red flag that hinted at the impending disbandment of the Fab Four.

Rather, a better argument can be made that longtime manager Brian Epstein's death in 1967 was the real beginning of the end of the Beatles. Yes, they still had the Midas touch as they kept putting out hits on the singles and album charts. But without Epstein's guidance and business acumen, the Beatles ended up making some questionable decisions, such as the 1967 film "Magical Mystery Tour," which was a flop with fans and critics alike. (The album of the same name thankfully didn't suffer the same fate.) Without Epstein to serve as a cooler head, tensions rose within the Beatles' camp as they created what would become the "White Album" in 1968. And one year later, the Beatles couldn't quite decide on whether they wanted Allen Klein or John Eastman (Paul McCartney's soon-to-be brother-in-law) to manage them. Much to McCartney's chagrin, the other three Beatles favored Klein.

All this happened after Epstein's death, and much of it played a significant part in the Beatles' breakup, which the band announced to the public on April 10, 1970.