The Complicated Psychology Behind Humans' Superstitions

It's surprising just how much many of us bow to superstitions in our everyday lives. We consider ourselves lucky or unlucky. We have various talismans and trinkets to try and ward away bad luck from befalling us. We wonder if, when it does, we "caused" it to happen by some seemingly unconnected unlucky act.

Avoiding cracks in the sidewalk, accidentally breaking a mirror and crossing the path of a black cat are just some examples of acts typically considered to be unlucky. Yes, it can certainly be unfortunate to pass beneath a raised ladder (especially if the person on it happens to carelessly drop something on your head), but it's interesting to consider why so many connect such supposed bad omens to indirect misfortune that happens later.

In 2013, the BBC reported that a OnePoll poll from Bic found that one-third of pupils questioned wore underwear they considered lucky when they took exams. They may have been better served studying for longer beforehand, but the poll also revealed that almost one-quarter of participants ignored that rather more logical approach and didn't study until the last minute. Here's why superstition continues to have such sway over our thought processes.

When logic and magic collide

A 2015 study called "Believing What We Do Not Believe: Acquiescence to Superstitious Beliefs and Other Powerful Intuitions," from Jane L. Risen (via the American Psychological Association), acknowledges how widespread irrational superstitions are. In an effort to explain this, Risen studies them through what's called a dual process model, in which "System 1 quickly and easily generates magical intuitions, which, once activated, serve as a default for judgment and behavior. System 2 may or may not correct the initial intuition. If System 2 fails to engage, then the magical intuition will guide people's responses."

Risen uses the term acquiescence to refer to the case in which superstitions are recognized as just that, but continue to be believed. "A person's cognitive skills can affect superstitious behavior by influencing whether or not System 2 identifies a magical intuition as an error," Risen writes.

If, for instance, a sports fan watching a match doesn't happen to be wearing their lucky team jersey that day (it might be in the wash, for instance), and the team still wins, they may not deem wearing the jersey a necessity next time. Or, perhaps, they may still feel that it'll help the team's chances to wear it anyway.

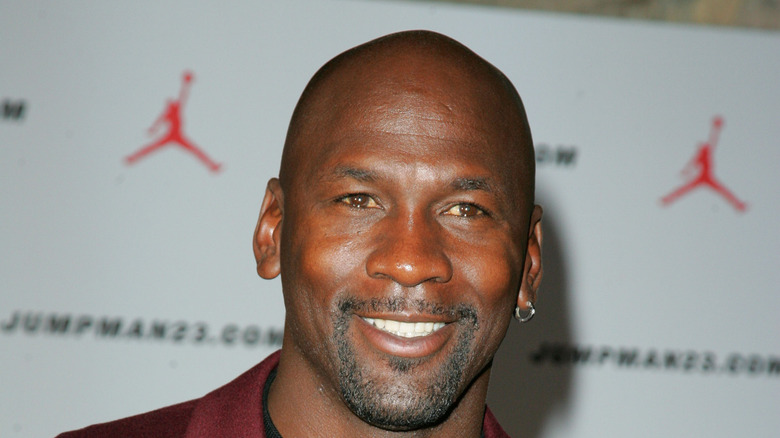

If it's good enough for Michael Jordan

As former Connecticut College Psychology Professor Stuart Vyse told The British Psychological Society, superstitions can have an "emotional benefit." They can make us feel braver, better, more talented, more equipped to challenge a world that leaves so much out of our control.

"There is evidence that positive, luck-enhancing superstitions provide a psychological benefit that can improve skilled performance," Vyse says. This, then, is where the placebo effect seems to come in. In his famous "Failure" commercial, Michael Jordan intones, "I've missed more than 9,000 shots in my career ... I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed."

During all of those many misses and failures, Jordan was surely wearing his famous lucky shorts — the University of North Carolina practice shorts that he wore to every single Bulls game under his Chicago Bulls shorts — per Tar Heel Times. After missing a game, did he declare his superstition "wrong" and eschew it? It seems not. This belief did not make him invincible, unbeatable, or superhuman. What it did seem to do, however, is inspire him to some of his greatest glories. If it helped even in the slightest to propel him towards being the greatest, it served its purpose. By the same token, if any superstition helps us to manage the world or alleviate our fears even a little, it's as understandable and rational as it is, by its very essence, illogical.