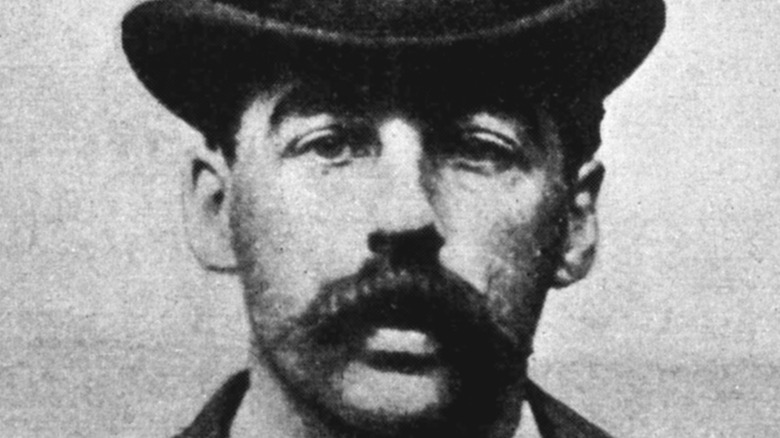

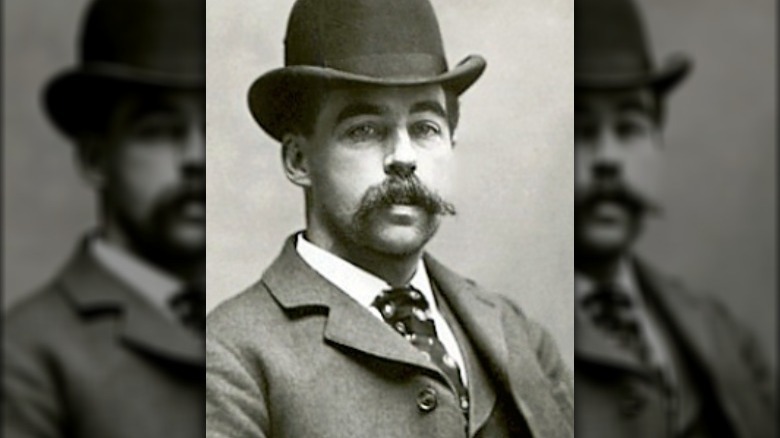

Who Were The Known Victims Of America's First Serial Killer, H.H. Holmes?

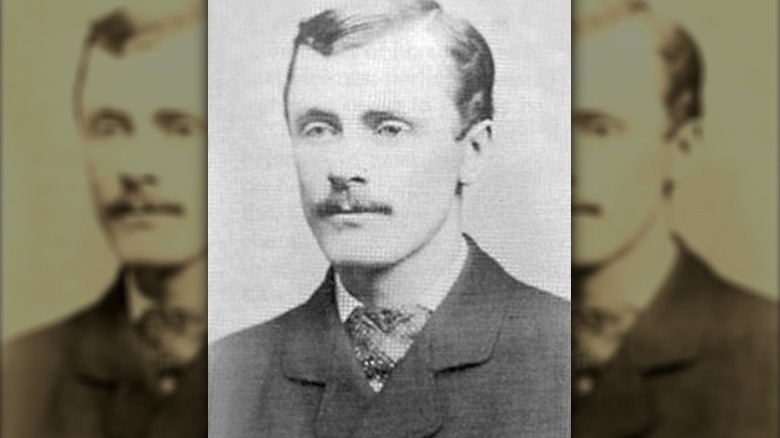

The infamous H.H. Holmes is best known for being the first serial killer in America ... that history remembers, at least. Interestingly, his criminal tendencies didn't start out so grisly. Holmes first waded into the shadowy underbelly of the still-young nation as a fraudster and swindler. His earliest crime — apparently — took place while he was attending the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor's medical college, which is where he acquired a body. Now in possession of the deceased, he collected the payout on the unfortunate soul's life insurance policy ... and Holmes? He didn't look back.

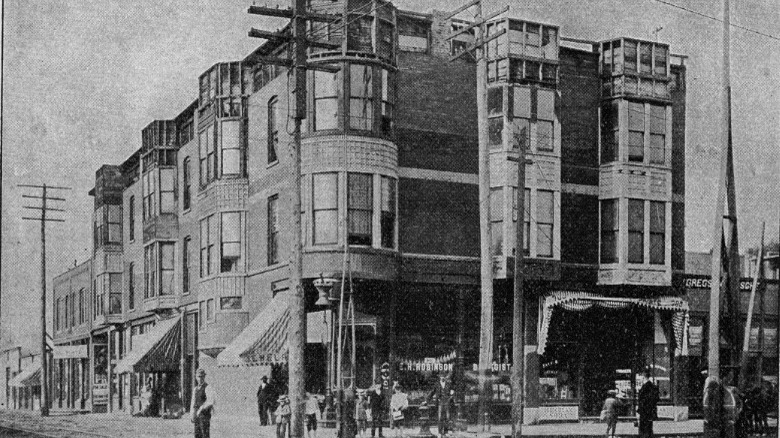

Holmes embarked on a series of bizarre crimes that not only lined his pockets but allowed him to establish himself as one of the fine, upstanding citizens of Chicago, which honestly says a lot more about society than it does about Holmes. As his ill-gotten gains continued to multiply, he eventually bought a building in the city's Englewood district, which would become notorious for being filled with secret passages, trap doors, and everything a good serial killer needed to continue his murdering ways.

So, who, exactly, met a tragic demise at Holmes's hands? All too often, tales of true crime focus more on the killers than on their victims, and it's worth remembering that they had fascinating stories of their own. At least, the ones that are remembered.

How many people did Holmes actually kill?

Exploring the lives of H.H. Holmes' victims is surprisingly difficult, for the simple reason that it's not known exactly how many people he killed. And it's not just that — estimates of how many victims there really were are all over the place.

Holmes, also known as Herman Mudgett, was arrested in 1894 and executed in 1896. It wasn't long before his own death that he sold his confession, which ran in the New York Journal on April 12, 1896, along with a handwritten note that swore this was the complete and honest truth. Only, it wasn't. Holmes wrote that he had killed 27 people, and he goes into just enough detail to make it sound plausible. However, when historian and author Adam Selzer started to fact-check Holmes's confession, he found that some of the people he'd claimed to have killed were still alive. Others seem to have existed only in Holmes's imagination.

Selzer says (via Mysterious Chicago) that this is enough to suggest Holmes' confession should be viewed with a healthy amount of skepticism. On the other end of the body count, there are still some who claim Holmes killed upwards of 200 people. However, that number wasn't actually even suggested until around 50 years after Holmes' execution, and the general consensus is that Holmes can be reliably linked to the deaths of only nine people.

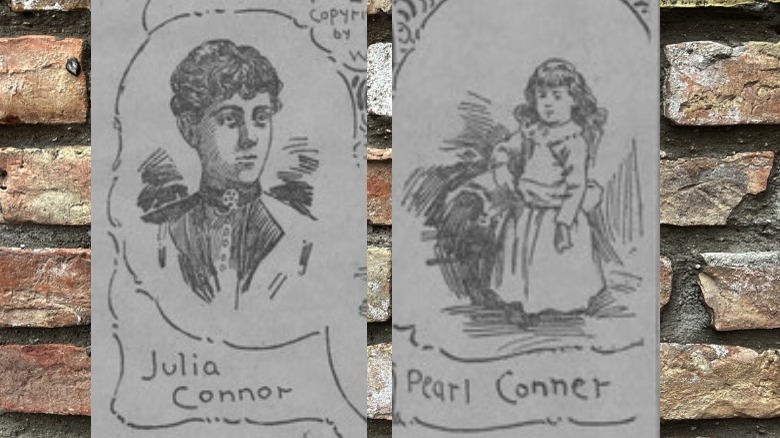

Julia and Pearl Conner

Julia Conner (sometimes Connor) and her daughter, Pearl, moved to Chicago in 1890. Harper's Magazine says Holmes was running the drugstore where Julia and her husband found jobs, but it wasn't long before things changed in a big way: Holmes bought the building that would become his infamous Murder Castle, and he did it with Julia on his arm.

Julia and Pearl moved in with Holmes. An important but brief aside, this is also around when Homes spent some time in Texas and met two sisters who would eventually also join him in Chicago. But for now, back to Julia and Pearl.

In "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil," author Adam Selzer reveals that the last time anyone saw Julia and Pearl alive was on Christmas Day of 1891. Holmes initially claimed Julia had left unexpectedly to visit her dying sister, then said she had fled her ex-husband. It wasn't until much later that he confessed he had killed them both. But again, the story of what happened isn't clear. Holmes claimed Julia died as the result of a botched abortion that he'd performed, and what happened to Pearl is even vaguer. Years after she disappeared, the bones of a young girl were discovered in the basement of Holmes's castle: They were the remains of 6-year-old (or possibly 8-year-old) Pearl. The motive was never established.

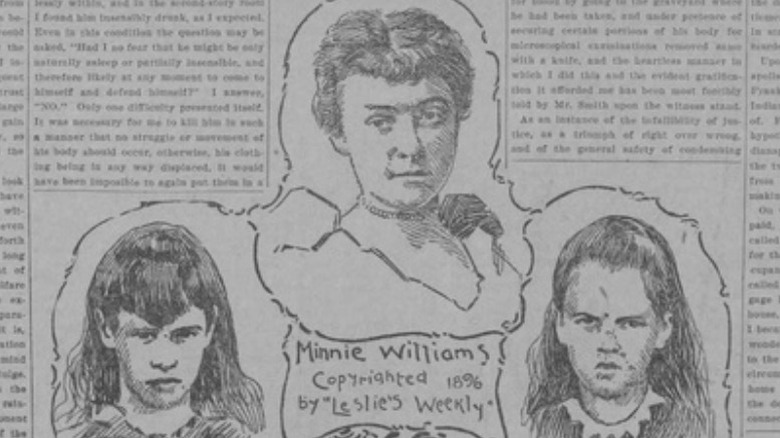

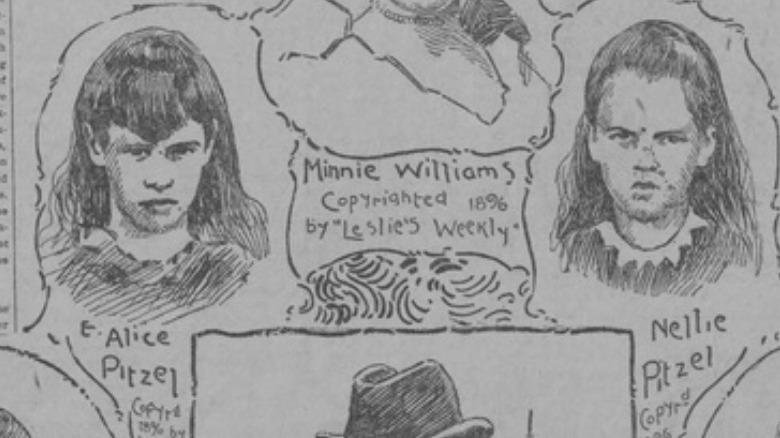

Minnie Williams

Minnie Williams crossed paths with H.H. Holmes during the Texas interlude in his affair with Julia Conner, says Harper's Magazine. Minnie would ultimately move to Chicago to be with Holmes, and the magazine suggests her involvement with Holmes was what led to the deaths of Julia and her daughter, Pearl.

When Adam Selzer dug into her life for his book "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil," he discovered stories of an intelligent and educated but aloof woman who had a gift for music and theater. She had performed in Boston, which Selzer believes is where she first met Holmes — who was then going by the alias Harry Gordon. Records show her moving to Chicago in 1893, when she ended up working as a secretary for Holmes. At the time, she had a nice little nest egg inherited in part from her uncle and in part from her brother. (He had died suddenly, and although there were rumors that Holmes had something to do with his death, that's debated.)

By the spring of 1893, letters from Minnie to her sister, Nannie Williams, indicate she believed she was married to Holmes, who she described as a wealthy doctor. And then, she disappeared. According to Selzer's findings, the last time anyone saw her alive was on July 5, 1893. However, Holmes would continue to use her name in future scams.

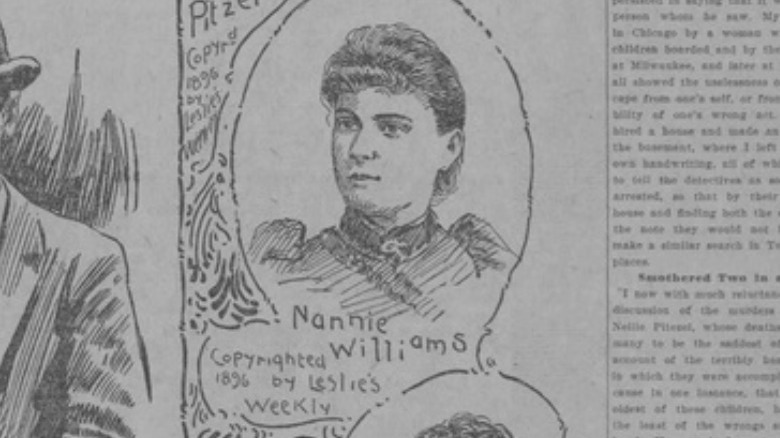

Nannie Williams

The unfortunate Minnie Williams wasn't the only member of her family to fall victim to H.H. Holmes. According to researcher and writer Adam Selzer, her sister Nannie was also killed in Chicago — likely by Holmes, although he also claimed that Minnie herself had been the one to murder her sister.

In "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil," Selzer says although that the sister is called by a variety of names, the most likely is Nannie. After Minnie headed to Chicago to start a new life, she wrote to Nannie and asked if she would join her and the man she said was her husband. (Selzer believes that Minnie was in on Holmes's scams at least to a point, although he says it's unclear whether or not she knew that property she owned was being used to build a house for Holmes's other wife and their child.)

On July 4, 1893, Nannie reportedly wrote a letter to the woman who had raised her after the deaths of her parents (although Holmes later said it was forged). In it, she said they were headed to Europe on vacation, and signed off with an eerie message: "Brother Harry [Holmes] says you need never trouble any more about me, financially or otherwise. He and sister will see to me. I hope our hard days are over." The day the letter was written was the last time Nannie was ever seen.

Emeline Cigrand

The story of Emeline Cigrand has eerie implications: According to "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil," her connection to Holmes and her disappearance almost went completely unnoticed. Holmes left little behind in the way of records about her, although she apparently worked for him for six months in 1892. Cigrand might have been completely forgotten if not for a relative who, luckily, recognized a newspaper illustration of Holmes's murder castle as being the place where his second cousin had worked.

Holmes reportedly hired Cigrand on as a secretary because of her connection to a doctor who peddled a "vaccine" said to combat alcoholism (Holes allegedly ran a similar scam). Those who knew the two spoke highly of her ... and not-so-highly of him, especially when it became apparent that he was interested in her in rather inappropriate ways, considering he was married.

Cigrand was last seen in December of 1892, and those who saw her in the weeks leading up to her disappearance reported that she seemed to have grown disillusioned with Holmes and their relationship. Her parents were told that she had run off to marry a man named Robert Phelps, who seems to have been fictional. Exactly what happened to Cigrand is unclear, but Selzer believes she was one of Holmes' victims.

George Thomas

After the arrest of H.H. Holmes, law enforcement, private investigators, and the media all scrambled to put together the pieces of his crimes. Scores of people who were missing — or not — around the time were thrown about as potential victims. According to Adam Selzer's findings, there was one person who was named as a victim who was nearly forgotten.

That was George H. Thomas, and there's not a lot that's known about him — aside from the fact that Selzer says he's one of the most believable stories among the many tales of alleged victims. The story Selzer uncovered was one that was reported in several papers, which claimed that Holmes and his then-partner Benjamin Pitezel were in Mississippi when they headed out onto the Tombigbee River with Thomas. And guess who didn't come back?

One of Holmes's wives reportedly had a signed confession from Holmes saying he and Pitezel dumped the body and went about their business. While that sounds incredibly unlikely, there is some intriguing evidence, like hotel registries, that put Holmes and Pitezel in the area. There was also a newspaper report that suggested the dead man was actually named Thomas Gregsan, but the story was never followed up on. Rumored documents containing more details were never released and are presumed lost.

Harry Walker

In "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil," researcher and writer Adam Selzer says that while there are a ton of stories about alleged victims that aren't very likely, one did seem plausible — the tale of Harry Walker, one of Holmes' employees.

Friends of Walker's received letters saying he was working for Holmes in Chicago in 1893, and not only had Holmes convinced Walker to work for him, but he had also reportedly convinced the man to do the not-at-all-suspicious thing of taking out an insurance policy for a whopping $10,000. (Adjusted for inflation, that's the equivalent of around $335,000 in 2022.) After accepting the job, Walker vanished.

Holmes and Walker didn't meet in Chicago, but in Indianapolis — and Walker's employment was seemingly verified by a letter he sent to his landlord confirming that not only had he accepted a job as the private secretary of a "Mr. H. Holmes," but also promised that he would return shortly to settle up on the rent and collect his things. When he didn't show up, the landlord reportedly thought he had simply decided to move on, and the fact that his name was such a common one made it impossible to trace any further.

Benjamin Pitezel

In 1894, Philadelphia authorities discovered the charred remains of a man who had been advertising himself as a patent-buyer named B.F. Perry. It was ruled he had died of an accidental inhalation of fire, with a little bit of chloroform for good measure. It wasn't entirely suspicious ... at first. That changed with a letter — written by a St. Louis attorney — claiming that the dead man wasn't named Perry at all, but Benjamin Pitezel.

Pitezel had a life insurance policy taken out on him the year before, and according to Harry Brodribb Irving's "A Book of Remarkable Criminals," Fidelity Mutual Life Association needed someone to identify the very charred remains, so they reached out to his associate, H.H. Holmes. Holmes was more than happy to examine and identify the now-disinterred corpse, and for good measure, he brought along the dead man's teenage daughter, Alice, to help identify his teeth. The insurance policy was settled, and Holmes walked away with $9,175 — or, about $318,000 adjusted for inflation.

Unfortunately for Holmes, he neglected to send $500 of that to a train robber named Marion Hedgspeth. Holmes met Hedgspeth in prison and offered him the money in exchange for the name of a lawyer who would be willing to write to the insurance company. Holmes didn't pay, and Hedgspeth went to authorities to say the whole thing was a scam.

Alice and Nellie Pitezel

Alice Pitezel, having identified her father's body in Philadelphia, left with H.H. Holmes, according to researcher Harry Brodribb Irving. Shortly afterward, Holmes showed up at the home of Mrs. Pitezel — sans Alice — to collect two of her other children, Nellie and Howard, allegedly to bring them to their sister. When Holmes was later arrested for insurance fraud, however, Alice, Nellie, and Howard were nowhere to be found.

Upon his arrest, Holmes admitted to insurance fraud, claiming the body found in Philadelphia hadn't been Pitezel's remains at all, and was instead a random corpse procured for fraudulent purposes. Pitezel and his children, he said, had ditched his wife and run off to South America.

But Holmes' stories kept changing. Even later, he claimed that his secretary Minnie Williams (after killing her sister Nannie) took the Pitezel children off on a European vacation. Clearly, something wasn't right here, and the case came to the attention of a detective named Frank Geyer.

Geyer, after tracking Holmes and the children across the country, finally came to a home Holmes had rented in Toronto, according to his book on the investigation, "The Holmes-Pitezel Case" There, in a shallow grave in the basement, Geyer and his team discovered the remains of Alice and — lying on top of her — her sister, Nellie. "Everybody seemed to be pleased with our success, and congratulations, mingled with expressions of horror over the discovery were heard everywhere," Geyer wrote.

Howard Pitezel

In his book "The Holmes-Pitezel Case," Detective Frank Geyer wrote that throughout the investigation, Benjamin Pitezel's wife clung to the hope that at least one of her missing children would return to her. With the grisly discoveries made at the home Holmes rented in Irvington, Indiana, that hope was snatched away.

Bizarrely, it was not Geyer who made the discovery, but two boys who happened to be at the home while the investigation was going on. Geyer wrote that "One of the boys suggested that they should play detective," and got more than they bargained for when they reached into an opening in the home's chimney. There, they discovered not only ashes but the remains of a femur and skull later determined to belong to a child about 10 years old.

DNA matching was, of course, decades in the future, but the identity of the remains was confirmed in what might be the most heartbreaking way possible. Howard Pitezel's grieving mother confirmed the coat left at a nearby grocer was her son's. The trunk found in Holmes's house, along with the contents, including shoes and a pin, was also Howard's. Witnesses who had seen Holmes with a little boy were shown pictures of Howard Pitezel, and confirmed his identity. Eerily, one of those witnesses was the owner of a repair shop Holmes visited to get his surgical tools sharpened.

The alleged victims, and why the truth is so hard to find

Surely, if H.H. Holmes had killed as many people as was claimed, there would be more confirmed victims ... right? That's part of what Adam Selzer researched for his book, "H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil." What he found was that there were doubts about even some of the widely accepted victims. Emily Van Tassel, for example, was often included on lists of reported victims, but Selzer says there's evidence that she was still alive in 1896 — after Holmes's arrest.

In other cases, Selzer couldn't find any evidence that some rumored victims had actually been real people, and some of the people who Holmes confessed to killing were definitely still alive long after his execution. So, why is the truth so elusive?

Holmes, it seems, was a product of his time. Harold Schechter, a historian, told History that even in the process of writing his book ("Depraved: The Definitive True Story of H.H. Holmes, Whose Grotesque Crimes Shattered Turn-of-the-Century Chicago"), he couldn't be sure what was true and what wasn't. The reason? Yellow journalism. At the time Holmes was killing, sensationalist headlines and bending the truth was the norm, as papers competed to see who could out-sell the others. A perfectly ordinary laundry chute became a chute for transporting bodies to the basement of a Murder Castle, nine victims became 27, and then 200. Consequently, the truth is likely to remain a mystery.