The Clock On Your Wall Actually Measures Space, Not Time

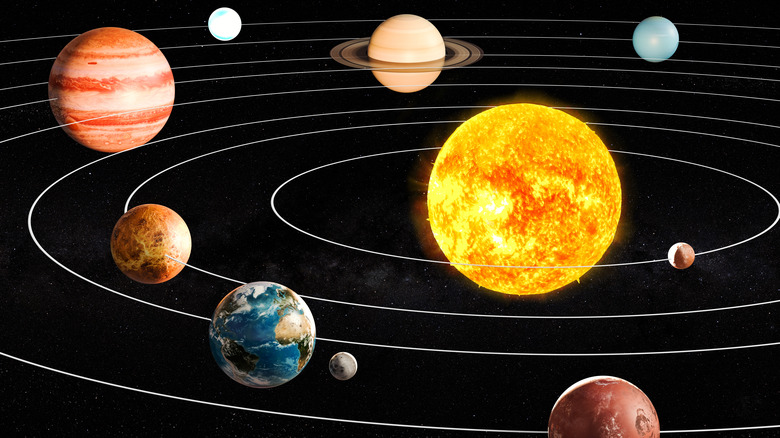

Hey, did you know that you're moving right now? No, you're not running (we suppose), driving (we hope), or jumping on a trampoline (we assume). But you're still moving. As Scientific American explains, you, the Earth, and everything on it is rotating like a spinning top at about 1,000 miles per hour. While rotating, we're all orbiting the sun at about 67,000 miles per hour. On top of this, our entire solar system is careening through our galaxy and orbiting the galactic center at a whopping 490,000 miles per hour. This means that all those static drawings you see of our solar system sitting still are wholly inaccurate. As Forbes shows, our solar system and its planets are constantly moving in a corkscrew, helictical motion like a school of frolicking dolphins through the ocean.

Now, go ahead and check the time. Maybe it's 2:00 p.m., 5:30 p.m., 8:47 p.m., whatever. What does it actually mean, for instance, to say that three hours have passed? It means that the Earth has spun 12.5% of the way around to its original starting position (three hours out of a 24-hour day). It's also traveled about 201,000 miles along its orbit around the sun. At the same time, it's traveled 1,470,000 miles in a corkscrew-like motion through the entire galaxy. Where is "time" in all this? What we call time, as measured by clocks, is actually a record of our position — using x, y, z coordinates — in space.

Relative motion, relative time

So how is it that you're moving in three separate ways (Earth's rotation, solar revolution, galactic revolution) along multiple axes in space (x, y, z) and feel still? Let's keep it simple and say: because you're already moving, as Forbes explains. Think of a car that speeds up, or turns suddenly, or comes to a quick stop: that's when you feel force pushing on you from some direction. Otherwise, you feel nothing because you and the car are moving at the same rate, in the same direction, smoothly and constantly. This — plus Earth's gravity locking us to the ground, the sun's gravity locking us to the solar system, and the Milky Way's gravity locking us to the galaxy — means that we feel blessedly, comfortably still.

Albert Einstein bundled up such thoughts — and much more — in his 1905 theory of special relativity. True to its name, it describes how space and time are not only relative but one single spacetime (discussed on Space.com). If you and your buddy are standing on a boat that's moving at 25 miles per hour, then you, your buddy, and the boat all appear stationary to each other. You could say that the outside world is whooshing by, or the outside world could say that you're whooshing by. Movement is relative. And time? Like we mentioned above, it's just another way to describe space. Objects moving at different speeds also experience time differently, especially when nearing the speed of light.

Time's arrow

Okay, you say, if a clock measures space, not time, does time even exist? How do we measure it? As Big Think describes, some researchers subscribe to block universe theory, saying that the past, present, and future exist all at the same time. But if that's true, then why do you remember the past — not the future — and only experience now? Does that mean we can't travel backward or forward through time like a million movies, books, and TV shows depict? NPR goes so far as to say that time is "an illusion." But that's not because time doesn't exist — it's because we've got our definitions wrong.

The truth is, we've got no handy wall-mounted, wrist-worn, or pocket-sized device to measure what we commonly mean by "time." Time, the moment-to-moment phenomenon experienced by humans, is different from the kind of time that describes space, ala Einstein's theory of special relativity. Our kind of everyday time — the kind that leaves us with chemical-electrical signatures in the brain called memories — is more accurately defined as a by-product of entropy. The second law of thermodynamics tells us that systems move from states of order to disorder, as Live Science explains. Our moment-to-moment experience of time is a result of an ever-disordered universe, aka time's arrow. Energy always seeks equivalency, like soup cooling to room temperature. That's why you experience time, and experience it unidirectionally. At present, though, there's no entropy-measuring clocks to hang on the wall.