Amazing Ancient Structures Carved From Solid Rock

People have been constructing living spaces for thousands of years, and several of the old buildings of the world remain in good enough condition that they're still in use today. However, while most construction involves masonry, cut stone, bricks, and mortar, the most remarkable human-made structures are hewn from solid stone. Known as rock-cut architecture, this is the painstaking process of carving structures out of cliff faces and hillsides. Remaining part of the Earth itself, this is known as living rock, and this unique type of masonry has been historically used across Asia and Africa, creating elaborate temples and tombs.

This particular type of masonry is an ancient art. Many of the finest examples of it can be found in South Asia, where the oldest rock-cut temples are frequently full of elaborate artwork and carvings, with impressively sized pillars and hallways. As The Architectural Review explains, some South Asian rock-cut architecture is older than the stone buildings which would later take precedence. These structures fall broadly into two categories, known as caves and monoliths, although the former name is a little misleading. Unlike natural caves, rock-cut caves are entirely artificial. Both are created from living rock in much the same way a sculptor might create a statue. Carefully cut, chiseled, and polished. With all the grandeur of the ancient buildings made by civilizations like the Romans or the Incas, this type of architecture can feel somehow even more impressive, with entire "buildings" created from single pieces of solid stone.

Petra

The ancient city of Petra is home to what are probably the world's most famous rock-cut structures, instantly recognizable from photographs. Petra may be little more than ruins now, but UNESCO explains that it used to be a Nabatean caravan city, with its origins lost in prehistory. In ancient times, trade routes would cross over land, connecting the civilizations of Egypt, Arabia, and Syria-Phonecia. Conveniently situated, Petra prospered as a vital crossroads on the long journeys. Between the Red Sea and the Dead Sea, the mountains all around Petra are full of gorges and natural passageways, no doubt inspiring the dramatic architecture which the Nabateans cut directly into the reddish stone cliff faces.

Known as the "rose red city," no one knows when exactly Petra was built. The reason it's so grand is that it was once the capital of the Nabatean Empire which flourished around the first century B.C.E. The Nabateans, a people from the Southeastern part of the Arabian peninsula, began as nomads. Over time, they amassed a lot of wealth as traders on the ancient Incense Routes, and the city of Petra, with its fusion of cultural influences, still stands as a testament to their significance in the ancient world. The most famous of Petra's stonework is known as Al Khazneh, The Treasury. A grand sight both for its size and for the care put into carving it. Less known but no less grand is Al Deir, The Monastery, also cut and carved from living rock.

Myra necropolis

Found in modern-day Turkey, Myra was once an important location in the ancient world. Part of the district of Lycia, little knowledge remains about its history, but it was a prominent part of Christian tradition, visited by Saint Paul and with Saint Nicholas as its former bishop. Myra is also home to the Myra Necropolis, a series of tombs carved from the living rock of the cliffside. Looking like something from a fantasy story, the angular-looking carvings date back to the fourth century B.C.E., per Atlas Obscura. They're subdivided into two sections, known as the ocean necropolis and the river necropolis. Many of the tombs are engraved with inscriptions, and some contain statues, seemingly bearing the likenesses of the occupant's family members.

The Myra Necropolis was also once vibrantly colorful, painted in hues of red, purple, blue, and yellow. Lavish tombs like these were typically reserved for the wealthier members of society, and such a big necropolis hints that Myra was once a prosperous place indeed. Often referred to as a town, inscriptions in Myra itself suggest it was far grander in the past. According to World Archaeology, the words quite literally written in stone describe Myra as being a "metropolis of Lycia." Alongside ornately carved bas-reliefs, inscriptions on the tombs are written in both Lycian and Ancient Greek, with heartfelt and endearing messages. Some tombs are even carved to resemble wooden houses, giving a somewhat literal meaning to the word necropolis, as a city of the dead.

Ajanta Caves

The Ajanta caves in central India are beautiful, ornate, and quite mysterious. A large complex of rock-cut architecture, they make up a Buddhist sanctuary carved into a horseshoe-shaped wall of stone. The Ajanta caves were left abandoned for nearly a millennium and a half, per BBC Culture. For an age, it was known only to the indigenous Bhil people, before it was "rediscovered" in the 19th century. Now officially recognized as a world heritage site, the oldest of the monastic halls in the Ajanta caves were carved around the second and first centuries B.C.E. An entire monastery once called this site home, and it was evidently an important enough location that around the fifth and sixth centuries C.E. the monastery was expanded, with several more chambers carved.

Every bit as remarkable as the stonework of the Ajanta caves themselves is the artwork that can be found there. The entire site is embellished with statues of Bodhisattvas and brightly colored paintings. In keeping with Buddhist ideals, the paintings are celebrations of mortal life itself, showing everything from ancient royalty to depictions of animals and nature, to scenes of lovemaking — the latter of which were considered shocking and offensive to British colonials. Elsewhere in the caves are paintings showing ancient Buddhist stories and depictions of the Buddha himself. The captivating artwork is even more impressive because the halls of the Ajanta caves are completely dark, meaning these paintings must all have been made by the light of oil lamps.

Kailasa Temple

Just under 20 miles from the city of Aurangabad in India's Maharashtra state, Kailasa Temple is the world's largest monolithic structure. A fabulous and beautifully ornate temple carved from living rock, it is part of a larger complex known as the Ellora Caves. One of 32 temples and monasteries, Kailasa temple was made for the Hindu god, Lord Shiva, and sculpted to resemble Mount Kailash, the legendary place in the Himalayas which Shiva calls home in the mythology of Hinduism, the world's oldest major religion.

Created in the mid-sixth century, Kailasa Temple is enormous, substantially larger than the famous Parthenon in Greece. Painstakingly sculpted using hammers and chisels, Lonely Planet explains that 200,000 tonnes of rock needed to be moved during its construction. With the rock out of the way, artisans set to work creating the elaborate carvings the temple is famed for. Its sculptures show scenes from Hindu scripture, like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Elsewhere are enormous reliefs showing the ten avatars of Lord Vishnu.

While Kailasa Temple may be the grandest among them, the other structures in the Ellora complex are no less impressive. Carved from basalt, a hard volcanic rock, the complex stretches for over a mile and was slowly carved over 400 years, between 600 and 1000 C.E. It also stands as a monument to the tolerant attitudes of Medieval India. The Ellora caves were constructed in a joint effort between three major religious groups: Buddhists, Jains, and Brahamanists (the predecessors to modern Hindus).

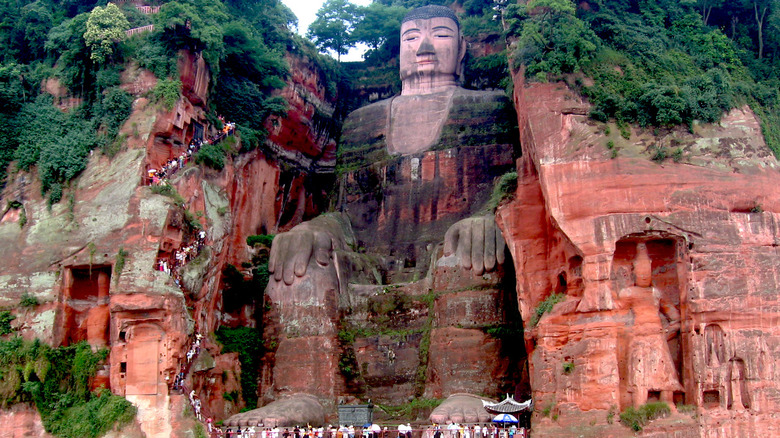

Leshan Giant Buddha

Giant Buddha statues can be found all over East Asia, but the one at Mount Emei in Sichuan, China, is one of the most remarkable. It's carved from the red stone of the mountainside itself, and for many years it was the world's largest Buddha statue (although it's since been surpassed by the Spring Temple Buddha, also in China). Per UNESCO, Mount Emei has been home to Buddhist temples since the first century C.E. It's an ancient sanctuary, where even some trees are over a thousand years old. The Buddha there was carved in the eighth century C.E.

Mount Emei holds deep and powerful cultural significance among Chinese Buddhists. It's home to the first Buddhist temple built on Chinese soil, constructed on the mountain's summit, which began the long tradition of Buddhism in East Asia. Since then, this mountain has become home to numerous temples and gardens, with a number of statues amongst them. However, the giant Buddha hewn from the red sandstone of Xijuo Peak is by far the most impressive statue on the site, and a major destination for pilgrims and tourists alike.

The Giant Buddha of Leshan took the better part of a century to carve from the mountainside. Per Atlas Obscura, its construction first began in 780 C.E. but, after some setbacks, it wasn't completed until 803 C.E. From its vantage point, overlooking the Dadu and Min rivers, a blessing from the Buddha is said to give protection to travelers on the water.

Lalibela churches

In the mountainous heart of Ethiopia lie 11 churches hewn from solid rock. With floor plans shaped like perfect crosses, they're remarkable for their precise and smooth carving, showing off breathtaking geometric accuracy. Per UNESCO, the churches were created in the 13th century, when the site was intended to be a kind of "New Jerusalem." After the Holy Land had fallen under Islamic control, it was no longer possible for Ethiopian Christians to make pilgrimages there, and the Lalibela Churches were intended to be a replacement holy site. They were built after the decline of the Empire of Aksum, when the Zagwe Dynasty took its place. The Zagwe kings were famous for their devotion to Christianity and their desire to build grand monuments to celebrate their faith. Overseen by King Lalibela, the churches are accordingly intricate in their construction. Carefully planned, they contain drainage systems, catacombs, and ceremonial passages. The interiors even mimic traditional construction styles, with archways and columns.

There's little surviving knowledge about who originally built the Lalibela Churches, carving them from the reddish iron-rich volcanic rocks which fill the surrounding landscape. Ethiopian Christians say they were constructed by angels and, with such fine craftsmanship, it's easy to see why they'd say this. There are three groups of churches at the site, and all remain in active use to this day. The area is an important location in Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, treated very much like the second holy land that King Lalibela had intended it to be.

Naqsh-e Rostam

Before Iran existed, Persia was once home to one of the great empires of Asia, and their kings were given suitably grand final resting places. Near Persepolis, the ancient Persian capital, lies Naqsh-e Rostam. It's named for a legendary hero named Rostam (sometimes transliterated as Rustam) who's still considered Iran's greatest folk hero. Legends say that he was the protector of the ancient Persian kings. Accordingly, the ancient necropolis of Naqsh-e Rostam houses the tombs of four kings of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. Cut into the cliffside, they have a distinctive cross shape and are sometimes known as the Persian Crosses.

The Achaemenid Empire thrived from 500 to 330 B.C.E., according to Atlas Obscura. Which kings are laid to rest here, however, is a little uncertain. One of them is definitely Darius I, also known as Darius the Great, an ancient king famous for his ambition in both construction and attempted conquest. The others are probably Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. It's likely the kings weren't placed directly into their sarcophagi though. Instead, chances are their bones were instead collected from the rooftops of towers of silence in accordance with Zoroastrian funeral practices.

The carvings around the tombs are also significant. Some show heavenly beings anointing the kings, while the reliefs around the tombs depict the ancient battles and victories of the Achaemenids. No doubt, these carvings were made to celebrate the accomplishments of these rulers in life, so they'd be remembered long afterward.

Mada'in Saleh

Mada'in Saleh, like Petra, was once a Nabatean caravan city. Its ruins still stand between Petra and Mecca, but most of what remains of the city today are tombs cut from rock. With some carved from the faces of the surrounding cliffs and others sculpted from gigantic boulders, the desert tombs of Mada'in Saleh are grand and imposing structures. The city is also known as al-Hijr or Hegra, and it was formerly the second great city of the Nabatean Empire. A striking sight in the desert landscape, it also stands as a testament to the prosperity the Nabateans enjoyed from the trade routes. Unfortunately, those trade routes dried up once the Roman Empire rose to power. With the Roman preference for trading by sea, fewer travelers passing through Mada'in Saleh led to the city being eventually abandoned.

There are a total of 131 tombs remaining at the site today, as well as religious places like altars which serve as reminders that the Nabateans were a pre-Islamic civilization. Much like Petra, the ruins of Mada'in Saleh also hint at the multicultural nature of Nabatean society, as a result of their extensive trading with other societies. According to UNESCO, there are influences all around the site from other ancient Mediterranean cultures. They show influences from the Egyptians, Greeks, Phoenicians, and Assyrians, and inscriptions include several languages alongside Nabatean.

Pancha Rathas

In conversations about India's finest rock-cut architecture, Pancha Rathas is often mentioned as a contender. Found in the state of Tamil Nadu, near the city of Mahabalipuram, it's an ornate and finely crafted temple complex. As The Telegraph of India explains, the site dates back to the seventh century and contains five finely crafted buildings and a handful of statues, all lovingly carved from the living rock. The number of structures in the complex is significant. The whole site is dedicated to the five Pandava brothers from the Mahabharata: Arjuna, Bhima, Yudhisthira, Nakula, and Sahadeva, together with their wife Draupadi. These brothers are the main figures from India's most famous Hindu epic tale, the Mahabharata, and their story is still a central piece of Indian culture in modern times.

The temples themselves, known as rathas, are a specific type of temple built in the form of a chariot, so the site has one chariot for each of the brothers. The stonework at Pancha Rathas is as intricate as ancient Indian architecture is known for, with finely sculpted reliefs, complex patterns, and pillars sculpted into the shape of animals. As with other sites in India, Pancha Rathas is just one of several rock-cut structures in the area. Also near Mahabalipuram are a group of sanctuaries called mandapas, cave temples that are decorated with fine stone carvings.

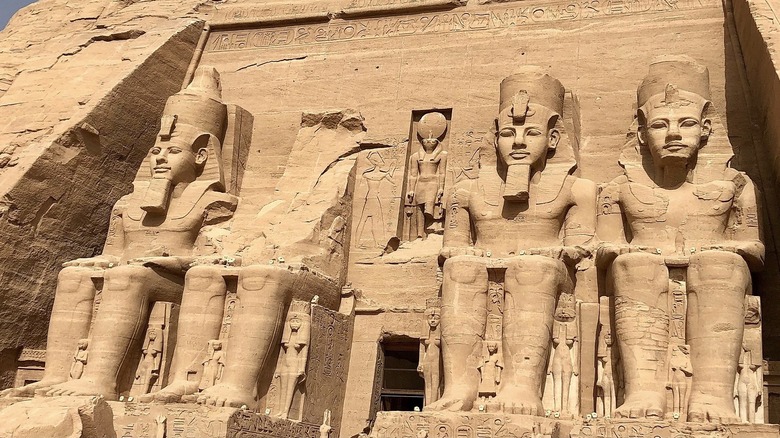

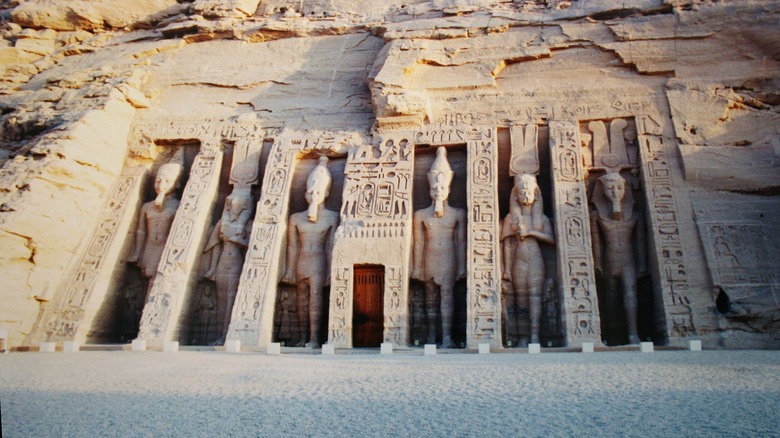

Abu Simbel

One of the oldest examples of rock-cut architecture in the world, Abu Simbel was created by the Ancient Egyptians and is home to two temples. Carved from cliffs made from sandstone, Lonely Planet explains that the main temple in the complex was created between 1274 and 1244 B.C.E. Known as the Great Temple of Rameses II, it was created to be the final resting place of the Pharaoh, and is guarded by four colossal statues of himself (although one is now severely damaged). In a remarkable feat of ancient engineering, the temple was originally designed with great care, so that sunlight would pass through the hallway and into the sanctuary on the anniversaries of Rameses' birthday and coronation. With the shifting of both the desert sands and the path of the river Nile, Abu Simbel was lost to the world for an age, until it was rediscovered in the 19th century by a Swiss explorer.

After its rediscovery, Abu Simbel soon came under threat in the mid-20th century, as a result of the newly constructed Aswan High Dam. As the waters of the Nile rose, a complex engineering project was needed to prevent the temple complex from being damaged. However, occasionally damage to ancient sites can be more useful than it may initially seem. Also found at Abu Simbel is ancient graffiti, carved by Greek mercenaries in the sixth century B.C.E. Their apparent vandalism inadvertently gave archaeologists a glimpse into the history of the Greek alphabet.