What Is A Mushroom Coffin? (And Why You Might Want To Be Buried In One)

These days, more people are turning to environmentalism and sustainability over excess and luxury. And, yes, this also applies to death. In recent years, green burial options, such as biodegradable urns and cardboard caskets, have become incredibly popular, and for a good reason. But, unfortunately, the death care industry is generally not eco-friendly. According to the Green Burial Council, 4.3 million gallons of embalming fluid are used annually in the United States. Likewise, an average casket is made with lead, zinc, and other metals. All this and more goes into the ground when an individual is buried, affecting the environment.

This also applies to cremation, which releases carbon and uses an exorbitant amount of energy. Enter researcher Bob Hendrikx from the Delft University of Technology and inventor of the "living coffin." Also known as the "living cocoon," this is a casket made primarily from mushrooms. He spoke to CNN about the rationale behind this creation and explained, "What really frustrates me is that when I die, I'm polluting the Earth. I'm waste." He continued to say that the body is a "walking trash bin of 219 chemicals."

Hendrikx hopes the "living coffin" will benefit the environment. He stated (via Dezeen), "We are currently living in nature's graveyard." Hendrikx added, "Our behaviour is not only parasitic, it's also short-sighted. We are degrading organisms into dead, polluting materials, but what if we kept them alive?"

This is why Bob Hendrikx chose to use mycelium for his living coffin

What's so special about Bob Hendrikx's living coffin? First and foremost, it's innovative. Hendrix and his startup company, Loop, designed the coffin to decompose quickly and provide nutrients to the soil it's buried in. While an average coffin can take up to 20 years to decompose, the "living coffin" only takes six weeks. Moreover, the body in a "living coffin" decomposes in three years rather than 10-plus years. It also eliminates toxic waste from the soil, which in turn, leads to new plant growth. Interestingly, the coffin only takes seven days to grow. Hendrikx uses a mushroom known as mycelium, a mold, and other substances to create the coffin.

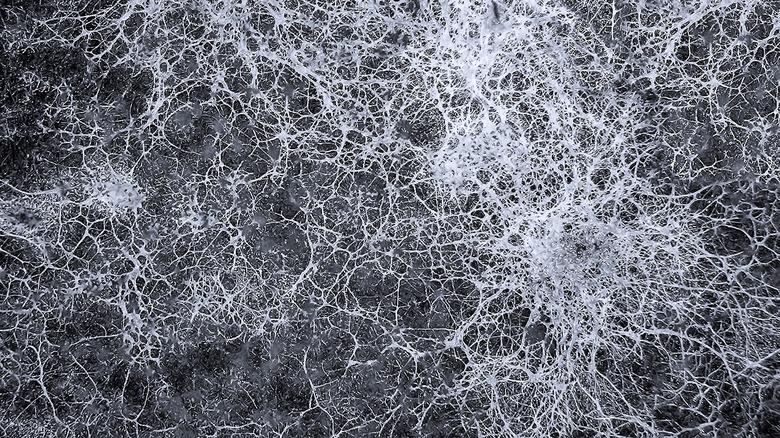

Nevertheless, Hendrikx notes that the key to his creation is mycelium. Decomposition occurs immediately when it touches damp soil. This mushroom is praised for its ability to break down toxic substances, heavy metals, and nonbiodegradable materials. In an interview with Dezeen, Hendrikx referred to the mycelium as "nature's recycler." He explained further and said (via Dezeen), "The Living Cocoon enables people to become one with nature again and to enrich the soil instead of polluting it." However, the "living coffin" is not the first time he's worked with mycelium. In 2019, Hendrikx made a small livable pod using none other than mycelium.

The first funeral that used a living coffin occurred in 2020

Although some might be put off by the idea of a "living coffin," Bob Hendrikx disagrees. In his eyes, this is how a burial should be. Hendrikx stated (via Phys), "This is the most natural way to do it ... we no longer pollute the environment with toxins in our body and all the stuff that goes into the coffins but actually try to enrich it and really be compost for nature." In 2020, an unnamed 82-year-old woman was buried in a "living coffin." Hendrikx did not attend the funeral, but he did speak to the woman's family.

He noted (via The Guardian) they were happy that "she will return to nature and will soon be living like a tree." Having said that, there are many pros to choosing a "living coffin." They are cheaper and lighter than a traditional casket. In 2021, CNN reported that a "living coffin" cost $1,700 and that 100 people had chosen it as their burial option.

Aesthetically speaking, the inside of the "living coffin" comes in a pale color and is lined with moss. Beyond those details, it looks like an average casket. This is perhaps what makes it so inviting. German funeral home owner Joerg Vieweg and buyer of "living coffins" told CNN that Hendrikx's invention works because it's still conventional and "a good example of how to achieve something ecologically with little change in the tradition of farewell."