The Iran Hostage Crisis Explained

Iran's authoritarian theocracy has faced protests sparked by its cruel tactics. But to understand current events, and how Iran's sitting regime came to power, it helps to know what transpired between Iran and America during the 1970s and '80s, how the West's reliance on fossil fuels shaped its Iran policy, and how CIA meddling in the region backfired spectacularly.

The latter culminated in the Iran hostage crisis of 1979, a byproduct of widespread Iranian anger over the West's siphoning of oil and sponsorship of Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. It all started when oil reserves were unearthed in Iran in 1908, after which British and American companies — particularly the company that is now known as BP — exerted near-total control over Iran's petroleum for roughly 40 years, according to The Wall Street Journal.

So you can imagine BP's reaction when Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq tried to nationalize the petroleum business in Iran. Mossadeq was a nationalist, and he and Pahlavi were political rivals, per Britannica. A contest for government control ensued after Pahlavi named Mossadeq premier as a sop to popular demand. But before long, because of Mossadeq's nationalization gambit, the CIA and British intelligenc engineered a coup and elevated Pahlavi, who promptly surrendered 80% of his country's petroleum to the West, according to History.

A repressive dictatorship

As a Western puppet, Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was all the CIA had hoped for; but as a long-term proposition, he was sorely lacking. The shah's secret police soon became notorious for torturing and disappearing dissidents and other Iranians. According to hostage Robert Ode's diary (via the Jimmy Carter Library), the students who would later overrun the United States embassy and take American hostages cited the belief that the U.S. had trained the police in torture methods.

The return to Western plundering of the country's domestic oil reserves also stirred popular outrage. And the shah's government-imposed Westernization of a conservative Islamic culture provoked a backlash in some quarters of society, per Britannica. The Pahlavi government also made no qualms about its relationship with the U.S., spending billions on U.S. arms instead of supporting Iran's economy, according to History.

Pahlavi's government started to receive more money from exporting oil in the early 1970s. And at that point, Iranians' issues with their government worsened, per Britannica. It was a prime example of the "oil curse": Political upheaval often follows the discovery of oil, particularly in poor countries, and the economic gains are seldom widely shared. As the Carnegie Endowment points out, rich petroleum reserves often have disastrous societal effects. They're correlated with corruption and civil strife, and can warp entire economies, and cause civil war.

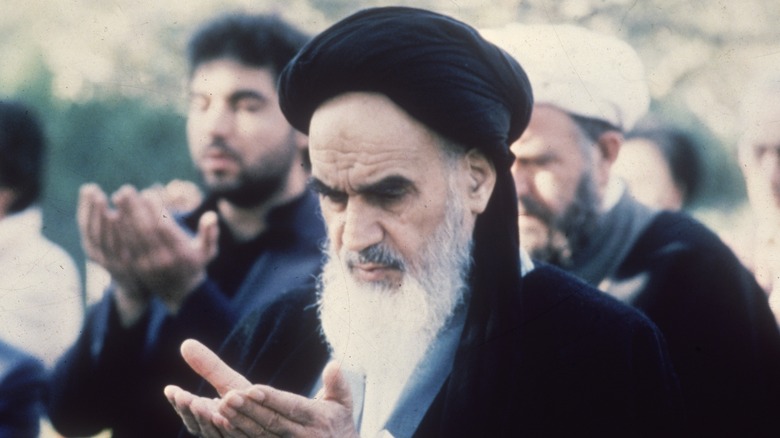

Ayatollah Khomeini rises

Iran's hardline Shi'ite cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had been driven out of Iran and was living in Paris around the time of the CIA-sponsored coup. He flew back to his native country in February 1979 amid widespread unrest in Iran's largest cities (which Khomeini had encouraged while exiled), per the BBC. Working-class supporters and religious scholars carried him to national prominence, notes Britannica.

Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi never formally gave up power. But that January, he high-tailed it to Egypt. By February, Khomeini and his followers were running things. And by April, Khomeini had a mandate to form an Islamic state based on the results.

Pahlavi, meanwhile, would eventually make his way across the Atlantic. Stuck in Mexico, he asked the U.S. government to let him into America so U.S. doctors could care for him. (The shah had a worsening case of cancer.) On October 21, 1979, the administration of then-President Jimmy Carter made the fateful choice to grant him safe harbor in America. It was a catastrophic move for U.S. citizens in Iran at the time, as William J. Daugherty, a former hostage who went on to become a specialist on the Middle East, wrote in American Diplomacy. There had been fierce internal debate over whether to let Pahlavi into America or merely to arrange "alternate havens" for him. But former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, and banking tycoon David Rockefeller reportedly lobbied Carter ferociously, and he eventually caved.

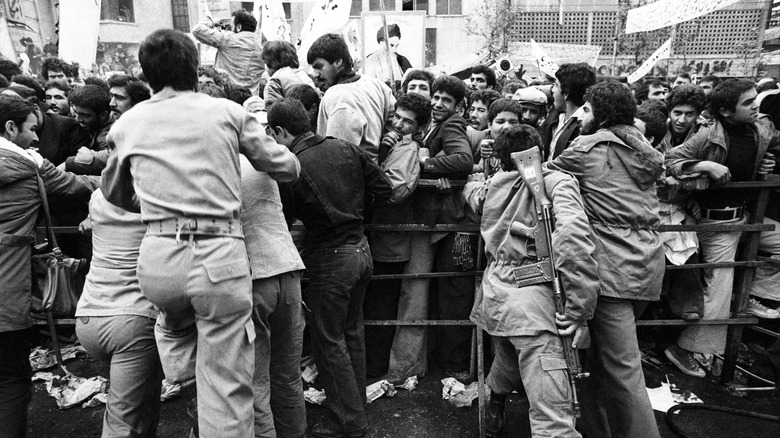

Khomeini's young followers storm the U.S. embassy in Tehran

Before long, it became clear that Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi had malignant lymphoma. But Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's followers didn't care. And sure enough, two weeks after the Carter administration let Pahlavi into America, all hell broke loose at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. On November 4, 1979, religious students burst through the gates, per History.

The students captured 66 people, mostly embassy staffers and military guards, and warned that they would murder them if American forces tried to save them. At the time, President Jimmy Carter vowed, "The United States will not yield to blackmail," according to Politico.

It's a bit of a mystery why the U.S. never tried to empty out its embassy preemptively given America's less-than-warm relationship with the new government in Iran and the warnings from embassy staff about the likely reaction in Tehran to the shah's arrival in the U.S. As William Daugherty explained in American Diplomacy, among other things, the Carter administration apparently never dreamed that Iranian officials would encourage students to seize the embassy's workers, who were supposed to enjoy diplomatic immunity.

Students release 14 hostages on Khomeini's orders

According to hostage Robert Ode's diary (via the Jimmy Carter Library), the students bound the hostages' hands and told them their anger didn't lie with those at the embassy and American in general but rather with President Jimmy Carter and his government. Nonetheless, they forbade the hostages to talk to each other. And they kept the hostages tied up 24/7 except when the hostages were eating or using the restroom. Days later, they took the hostages' accessories and other possessions, including wedding rings and wristwatches, and moved them to another location: a poorly ventilated warehouse with disgusting toilets.

Before long, the students let 13 hostages go, primarily minorities and women. Due to "the oppression of American society," these people had suffered enough before they were ever taken hostage, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini said by way of explanation for their release, per History. Another hostage experiencing medical issues was released soon thereafter.

The 52 hostages still in custody were told to sign a petition demanding the U.S. government return Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi to Iran so that the students could release their captives. Representatives from the pope and from the Belgian and Syrian diplomatic missions stopped by, with little to no effect. "They just walked through — had no conversation with us, and just looked at us as though we were animals in a zoo!" Ode wrote in his diary.

Operation Eagle Claw

Between late 1979 and the spring of 1980, the Carter administration bargained with Iranian officials, trying to secure the hostages' release. Then, after months of failed negotiations and ineffective economic sanctions, President Jimmy Carter decided to try to get the hostages out of there using the armed forces, per History. Some Carter White House officials reportedly warned him against this mission.

The goal of Operation Eagle Claw was to drop a team of Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine soldiers into the location where the hostages were being held and cart them out, according to Britannica. But from the beginning, the mission was beset by problems. A dust storm made it hard to see and steer, and two helicopters turned back after suffering technical glitches. By the time the rest of the helicopters reached the landing zone, they were 90 minutes behind schedule. Ultimaely with too few helicopters, the military deemed it impossible to carry out the mission.

In the process of aborting, one of the helicopters ran into an aircraft. The resulting explosion left three Marines and five Air Force servicemembers dead. The mission was a failure in all respects, and while the military learned some lessons from the experience — developing the "joint doctrine" to prevent coordination miscues in the future, and launching the U.S. Special Operations Command — Operation Eagle Claw's flop did nothing to help the Carter administration.

Meanwhile, at the hostage compound...

By April 25, 1980 — the day of the failed rescue attempt — the Iranian students had divided the hostages into "dangerous" and less dangerous camps, according to hostage Robert Ode's diary (via the Jimmy Carter Library). Some of the hostages were reportedly tortured and put through "mock executions" during this period, per The New York Times, and even the ones who were treated slightly better, like Ode, endured constant discomfort and psychological strain.

The latter included Ode being told that day that he would be moved to "a much, much better room" and then, after a long wait, being told that he would have to stay in the grubby room where he had been imprisoned for months, after all. The Iranians did, however, move his roommate to different quarters. (Upon learning of this, Ode lambasted his captors, who told him: "Older men should be more polite!")

On that day, Ode heard a ruckus near the embassy compound — probably the reaction of Iranians on the street to the news of Operation Eagle Claw. The students' decision to abruptly shift their hostages around was likely a response to that mission, which they never discussed with their hostages. The students apparently decided not to kill hostages in retaliation for the rescue gambit.

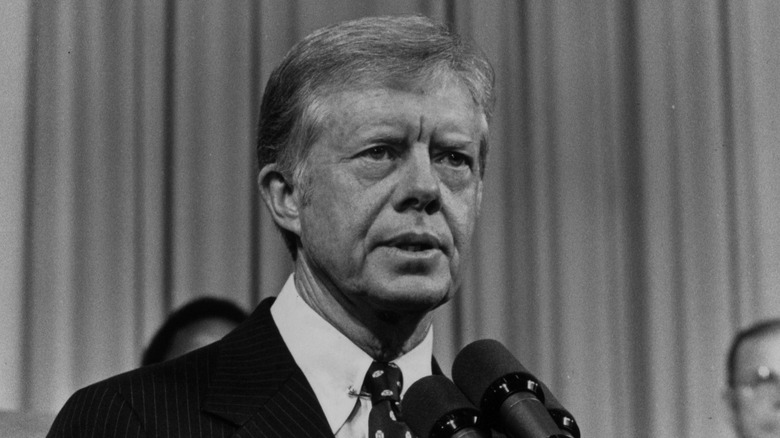

The crisis contributes to Jimmy Carter's election loss

In the lead-up to the 1980 presidential election, Jimmy Carter was back to negotiating with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's regime. At that point, national media outlets were laser-focused on the Iran issue, according to History. Filmmaker Robert Stone has said the start of the 24-hour news cycle can be traced to these events — his documentary about the crisis as released in 2022, per the Albuquerque Journal. Ted Turner started CNN in June 1980, right in the midst of the 1980 campaign, so the hostage crisis coincided with the rise of cable news — which quickly drove the ascendance of punditry and infotainment over more substantive coverage, per Britannica.

When Carter failed to secure the hostages' release, it didn't help his standing with voters. As political expert Elaine Kamarck observed for the Brookings Institution, the blame for their continued captivity was on his shoulders, with voters deeming him "weak and feckless" due to his inability to secure their release. Moreover, Kamarck, who was working for the Democratic National Committee in Washington, D.C. at the time, recalled that Carter's people immediately realized the costs of Operation Eagle Claw; a White House political operative reportedly called her on April 25 and said simply, "We just lost the election."

The domestic economy was tanking by then, and with a few exceptions, the voters who didn't abandon Carter over the economy abandoned him due to the stalemate over the hostages. Come election time, Carter only won six states and Washington, D.C.

Iraq invades Iran, kicking off the Iran-Iraq War

As President Jimmy Carter was losing his re-election fight, another battle was taking shape in the Middle East: On September 22, 1980, Iraq invaded Iran by air and by land. Here's why: Previous borders seemed up for grabs given Iran's regime change. And Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein thought the Iranian Revolution might infect Iraq's Shi'ite population, per History. The war came too late in the U.S. presidential campaign to help Carter, but it would prove a fateful development for Ronald Reagan.

The Iraqi army invaded Iran at Khuzestan, according to Britannica. Iranian forces, especially Ayatollah Khomeini's domestic enforcers, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), fought back. Soon, Khomeini's administration was entrusting the IRGC with defending Iran from invasion. Iranian forces beat back the Iraqi army, which eventually retreated back toward Iraq.

Before long, Khomeini would launch a counter-invasion aimed at regime change in Iraq. He believed Hussein was hostile to his agenda, perhaps justifiably, but he may have had another reason, too. According to Britannica, the fighting raged primarily in the areas of both countries where oil reserves sat.

Isolated, Iran's government finally negotiates in earnest

With Iran's government under siege at home and isolated internationally because of its hostage-taking, it suddenly had a sincere interest in ending the crisis. Another development had also rendered the Iranians' top demand moot: On July 27, 1980, Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi died of cancer, per Britannica.

The U.S. embargo on Iranian goods was taking a toll on Iran's economy. And that October, the Iranian prime minister went to the United Nations' headquarters in New York hoping to secure international backing in the Iran-Iraq War. However, he was reportedly told by heads of state there that no such backing would be forthcoming, according to Britannica.

So, with Algerian diplomats serving as messengers, talks began in earnest. By now Iranian officials' top priorities were unfreezing Iranian assets and rolling back the embargo. As the U.S. election passed, negotiations continued. By 1981, Ayatollah Khomeini's bete noire, Jimmy Carter, who had made the consequential decision to allow Pahlavi into the U.S., was on his way out of the presidency.

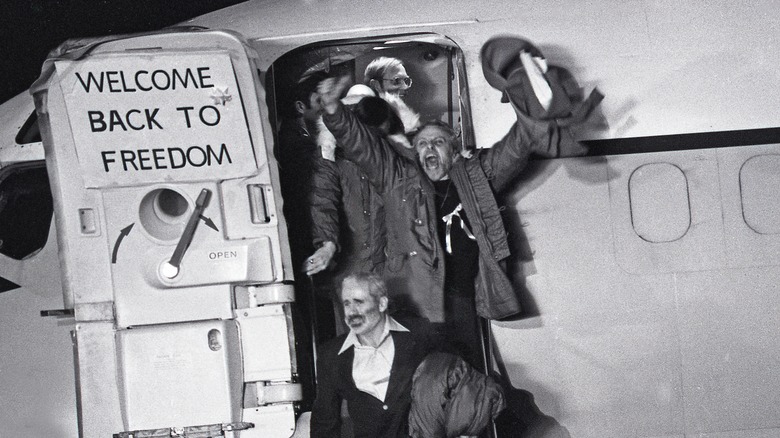

As Ronald Reagan is inaugurated, both parties agree on terms

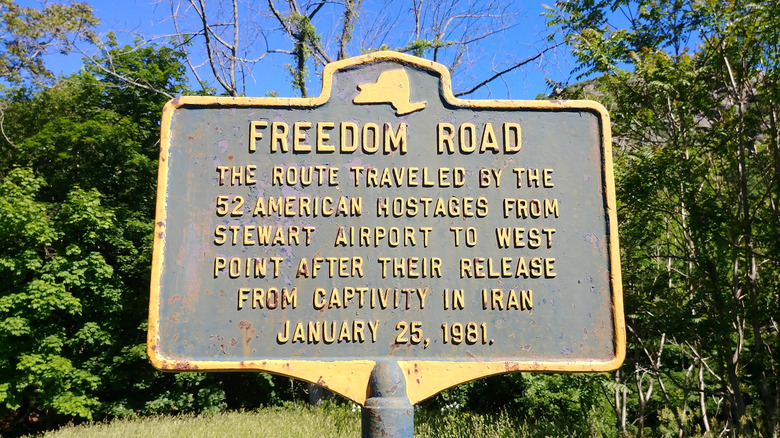

In early 1981, an agreement was reached. The U.S. unfroze $8 billion of Iranian funds, per History. And the hostages were released on January 20, 1981, 444 days after the students crashed through the doors of the Tehran embassy, and less than an hour after Ronald Reagan took office as president, according to Britannica.

Carter officials — notably, Gary Sick, a Carter White House staffer who worked on the Iran hostage crisis — later accused the Reagan team of negotiating a closed-door deal with a high-ranking Khomeini regime official that blocked the hostages from being freed before Reagan took office, per The New York Times. Sick was preparing to release a book when he made that allegation in a Times Op-Ed.

Sick cited as his informant an Iranian weapons dealer who reportedly claimed that he and his late brother had set up the secret meetings at a Madrid hotel. But Reagan officials, including then-President George H.W. Bush, fiercely contested Sick's charges. While Sick's claims are now repudiated, according to Britannica, some still question the timing of the hostages' release. It may be that Ayatollah Khomeini and his people simply disliked Carter and wanted to bring down an American president for their own reasons.

The aftermath of the hostage crisis in America

Upon their return, the hostages suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Some had been starved in Iranian custody; most had believed they were going to die. As for the Iranian students, they displayed psychotic levels of paranoia as time wore on. "We were treated miserably, but they were constantly afraid of us," former hostage Barry Rosen recalled to the New York Post. "They thought we had some way of getting out. They checked our shoes for radios, as if we were Dick Tracy."

The U.S. government later compensated the hostages for their ordeal. And in 2019, the Department of Justice included them in a $1.075 billion windfall. That pot was shared with other former hostages and targets of terrorism. (At least some of the money they received came from penalties paid to the U.S. government for sanctions violations.) In 2020, a lawyer representing former hostages told The New York Times that his clients continued to suffer debilitating aftereffects; for example, one hostage reportedly has to "receive institutional help" whenever Iran makes headlines.

As for the broader effects of the crisis, it was a humbling moment for America, coming not long after the withdrawal from Vietnam. And it probably should have tempered American officials' ambitions about intervention in the Middle East. But history shows that it did not.

The aftermath of the hostage crisis in Iran

From Iran, things looked somewhat different. To his people, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini continued to cast the U.S. as bogeymen, and after he died in June 1989, his successor, former Iranian President Ali Khamenei, picked up the torch, per The Middld East Media Research Institute. But among many of Iran's people, the Iranian Revolution seems to have given way to some combination of disappointment, resentment, and resignation.

Speaking to a reporter for the Associated Press on the 40th anniversary of the hostage crisis, Iranians on the street shared bittersweet recollections of that moment in Iran's history. "I had a good feeling then, but we have had a bad fate," Hossein Kouhi, who claimed he was among the anti-American demonstrators on the streets during the hostage crisis, said. "It changed the world as I knew it," photographer Kaveh Kazemi told the newswire.

Still, Iranians pointed to U.S. interventions in other Middle Eastern countries, to violent American films, and to U.S. sanctions that have hobbled the Iranian economy as reasons for ongoing hostility and mistrust. By that anniversary, Iranian officials had rechristened the former U.S. embassy site "the Den of Espionage" and arranged to have its walls plastered with anti-American slogans.