How A Team Of Researchers Decoded 400-Year-Old Letters From Mary, Queen Of Scots

For more than 400 years, a set of 57 letters sat in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the country's national library, virtually untouched. They had been cataloged as Italian texts of unknown origin. But when a team of code-breakers came across the items in the library's online archive, they realized it was something else altogether. The team — a Japanese physicist, a German pianist, and an Israeli computer scientist — determined the letters were not Italian by at all. "We were expecting Italian because that is what the catalog said, but then we started to see some French words — 'ma liberté' (my freedom) — and sentences no one would write if they were free," George Lasry, the Israeli computer scientist, told the BBC.

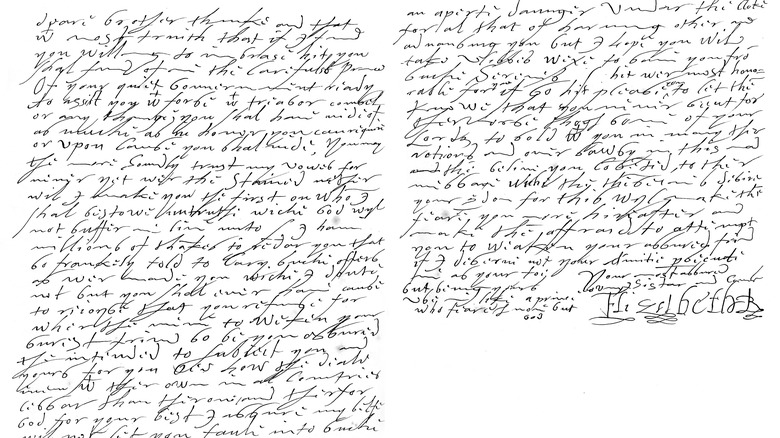

What the team quickly realized is that the letters were deeply coded texts designed to throw off any potential interceptors from knowing their meaning. The team had a couple of clues as to who penned the letters. For example, the language was in feminine form, so they knew it was a woman author. And she wrote "mon fils" (meaning, my son), so they knew she was a mother. However, Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer, Norbert Biermann, a music professor, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, a physicist, knew the only way to truly know the story of the mysterious letters was completely dependent on them breaking the complex code. So, the team set forth to decipher the 57 letters that contained 50,000 words and more than 150,000 symbols.

An incredible discovery

The letters revealed the secret correspondence of Mary, Queen of Scots. "We found treasure lying in plain sight," George Lasry told The New York Times. Mary, Queen of Scots remains one of the most fascinating figures in European history. She became the queen of Scotland in 1542 when she was just 6 days old. But in an uprising, she was imprisoned and forced to abdicate her throne in 1567 in favor of her son, James VI, who was just a year old. Still, Mary Stuart managed to escape to England, where she was jailed once again by her cousin Queen Elizabeth I (above), who saw Mary as a threat. At age 44, after nearly 20 years as a prisoner in England, Mary was executed for an accused Catholic plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, a Protestant, per the National Museums Scotland.

Nearly all the letters are from Mary Stuart to the French ambassador to England, Michel de Castelnau, who supported her claim to the throne. The letters were written between 1578 and 1584 and included details about her diminishing health, her conditions in captivity, and her struggle for freedom. "I cannot thank you enough for the care, vigilance and entirely good affection with which I see that you embrace everything that concerns me and I beg you to continue to do so more strongly than ever, especially for my said release," Mary wrote to de Castelnau in a letter dated April 16, 1583, per Cryptologia.

Mary was a diplomat

Although Mary, Queen of Scots had a reputation for her political acumen, the letters reveal she could display diplomacy skills, too. In another letter to de Castelnau, Mary attempted to smooth over potential conflicts of interest as he tried to help her in her quest for freedom. "I know that you have been careful, in the name of the king [of France], to mitigate the outbursts of anger of the queen against me, who wishes her nothing but good in spite of all the harm I have suffered from her," she wrote, per Le Monde.

For historians, the revelation is intriguing. "She's negotiating with the Spanish, with the French — evident in these letters — with Scotland and with Elizabeth. And it really does deepen our sense of her as a political animal, not just as a captive queen," Susan Doran, a historian at the University of Oxford, told Scientific American. "There's much more to Mary than the plotting."

According to Ars Technica, Mary protected her letters with a process called "letter-locking" (via YouTube). She was also trained in cipher by her mother, Marie de Guise, at an early age, and her techniques were sophisticated. George Lasry told The New York Times that Mary's codes included hundreds of symbols that could be stand-ins for letters, numbers, and names. The process of deciphering it all took a lot of time. "It was kind of like an onion you have to peel," Lasry said. "We had to work layer by layer."