The History Of Spy Balloons Explained

Common images of espionage, shaped by popular culture, often involve elegant and ruthless agents on the ground or the most sophisticated and advanced technology. It's a picture with some truth to it. Human actors are at the heart of espionage, and the latest tools are always incorporated into reconnaissance. But while a satellite can survey suspicious territory or activity at a safe distance and hacking can uncover troves of sensitive material, such methods are expensive and highly specialized. Sometimes, old-fashioned techniques are more practical.

One such method is the spy balloon. As explained by Politico, balloons have a low fuel demand, can carry heavier things than current drone models, and come in for a relatively low price tag. Professor John Blaxland told The Guardian that the number of satellites and debris in orbit around Earth has made the upper atmosphere, where balloons can easily travel, ideal surveillance territory. It's also easier to disguise a balloon as an innocuous civil craft.

Such advantages have kept spy balloons in use by military and intelligence agencies throughout the world in recent years, and are likely to keep them in demand for some time. But the idea of using balloons to scout, deceive, and even attack goes back centuries. Here's the history of spy balloons, explained.

The first balloon unit was used in the French Revolutionary Wars

The French pioneered manned ballooning, with the first successful effort completed over Paris in 1783 (per the National Balloon Museum). The application of flight to war and espionage came 11 years later. By that time, the French Revolution had torn through the country and France was engaged in a series of wars with several European states. The technology behind ballooning had also advanced to the point where balloons powered by hydrogen gas could retain altitude for longer durations.

According to Historic Wings, the first French Aerostatic Corps was formed in 1794, under the command of chemist Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle. Their job was to fly over enemy lines and alert their own forces to developments through signals or dropped messages. Their value was demonstrated at the Battle of Fleurus, where timely reports by the balloonists helped keep Austrian and Dutch forces from penetrating the French lines.

The Aerostatic Corps saw regular use throughout the French Revolutionary Wars and was greatly prized by General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. But one commander didn't share Jourdan's enthusiasm. According to L. T. C. Rolt's "The Aeronauts: A History of Ballooning, 1783-1903," Napoleon Bonaparte was offered to use the Aerostatic Corps for his 1797 Egyptian campaign. But Napoleon reportedly scorned the use of reconnaissance balloons as unmanly. The corps' equipment was destroyed in the Battle of Aboukir, and when Napoleon returned to France, he not only disbanded the regiment but cut off all investment in military ballooning.

The Union and the Confederacy both fielded balloons during the Civil War

As noted by the National Park Service, both the Union and Confederate armies had balloon units active throughout the American Civil War. The balloons used could carry one to five people, depending on size, and reached altitudes of 1,000 feet. Maintaining a connection to the ground through ropes, those flying the balloons would scout out enemy troop movements and relay the information with flags or with portable telegraphs.

The Union's balloon corps came under the command of Thaddeus Lowe. Per the Wolbach Library's Galactic Gazette, Lowe was a self-taught enthusiast of ballooning who was captured by Confederate forces during a recreational test flight. After being cleared of espionage charges and sent back north, Lowe promptly became involved in the very work he'd been accused of. He was placed in charge of the balloon corps and led them for two years, never losing a balloon despite repeated efforts by the Confederacy to shoot them down. Confederate efforts to mimic the Union's tactics with their own balloon fleet were only marginally more successful.

Bureaucratic infighting cost Lowe his corps in 1863, and the unit never saw use under General Ulysses S. Grant in the final years of the war. Lowe's interests shifted to freezing technology, and he declined all offers to share his knowledge and experience with other countries inspired by his success with balloon espionage.

They were a limited aid to the British Empire

The most iconic vehicles of the Royal Air Force are probably the Spitfires that faced down the Nazi Messerschmitts during World War II. But any kind of airplane was a far-off dream in the 19th century when the British Empire was expanding through Africa. Then, the only aerial option for warfare was ballooning.

Elements within the British military had an interest in making use of balloons as early as 1862, according to the Royal Air Force Museum, but the army didn't begin testing their worth until 1878. Over the following decade, they were deployed on campaigns in South Africa and Sudan. After 1890, a dedicated section of the Royal Engineers, with a supporting school, was created to provide aeronautical services.

Three units of balloons were sent to aid British forces in the Boer War in 1899. According to the Royal Air Force Museum, they were ordered to perform reconnaissance ahead of the Battle of Magersfontein, but their work was of limited value. This had less to do with any limitations of the balloons and more to do with commander Lord Methuen's refusal to wait for them to arrive. By committing to an attack a day before his air cover's arrival, Methuen probably wrote his own defeat. But in the aftermath, he told his superiors that the intelligence gathered by the balloonists during the battle after they arrived was invaluable.

Brazil used a balloon corps in the War of the Triple Alliance

The successful use of spy balloons by Union forces in the American Civil War inspired other nations throughout the 19th century. The War of the Triple Alliance, a conflict between Paraguay on one side and Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay on the other, began in 1864. According to André Reyes Novaes' paper in Investigaciones Geográficas, fighting within Paraguayan territory was complicated by the allied forces' limited knowledge of often swampy terrain. To counter this, Brazilian commander Luis Alves de Lima e Silva put a new unit into the field in 1867: the balloon unit.

The founding members of the Brazilian Balloon Corps came from the United States, according to Terry D Hooker's "The Paraguayan War." James and Ezra Allen were brothers who had carried out reconnaissance for the Union under the command of Thaddeus Lowe; Lowe had been approached by Brazilian agents to develop their balloon corps, but he declined and recommended the Allens in his place. Lowe was also the designer and builder of the two balloons his proteges brought to the war.

The Allens, with occasional Brazilian officer passengers, remained tethered to the ground for all their reconnaissance work. As soldiers held the ropes and guided the balloons, the brothers observed and mapped the terrain. The War of the Triple Alliance went on until 1870, but it ended in an allied victory, and the efforts of the balloon corps were highly commended.

Ballooning espionage became more widespread in World War I

Among World War I's dubious honors is the advances in military technology employed by all sides during the conflict. This included innovations on the spy balloon. According to the World War I Museum and Memorial, three types of balloons saw use during the Great War. The tethered balloon, also called a captive balloon, operated on the same principles as balloons used in the prior century. Controlled by operators holding the ropes anchoring the balloon, aeronauts would observe and report on enemy movements and the condition of the terrain. Advances in binoculars improved on past limits to visibility.

World War I also saw the deployment of what were called free balloons, or balloons with no tether. The difficulty in steering them made them ill-suited for spying, but they were often used for another sort of intelligence work. Allied forces used free balloons to disperse propaganda leaflets aimed at demoralizing the Central Powers.

The third class of balloon used in World War I was the dirigible. Much larger than other balloons and loaded with engines and equipment, dirigibles were limited in movement, but they could maintain a position for longer periods than other balloons and so allow the crew aboard to gather more intelligence. As the war progressed, their ability to carry heavier loads also saw them used offensively: A dirigible could be loaded with bombs.

Balloons could be used on the ground in World War II

Besides reconnaissance, military balloons were put to another purpose in World War II: obfuscation. According to the National Air and Space Museum, the use of large balloons to provide cover against enemy fire began in Europe during the first world war. These large silver craft were floated above cities, infrastructure, and advancing troops at relatively low altitudes. They kept opposing planes from getting too close, limiting the effectiveness of bombs or gunfire. The tethers of the balloons posed a threat to passing planes, forcing them into higher altitudes where they could be more easily intercepted.

While successfully employed by Allied forces in World War I, the United States was slow to adopt these barrage balloons, as they were known, for its own military. Besides limited funding, any advancements in the American balloon program were frustrated by competition among the branches of the armed forces over control. The situation wasn't resolved until 1941, when Camp Tyson was formed in Paris, Tennessee to develop America's balloon fleet.

Barrage balloons were used on the home front as a safeguard against possible follow-up attacks by Japanese forces on the west coast, and on the front lines of Europe. D-Day saw the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion flying over the landing ships off Omaha Beach.

Japanese forces weaponized balloons in World War II

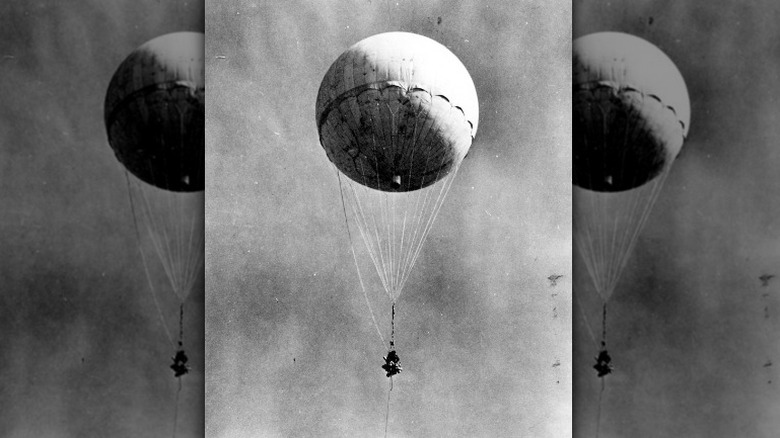

Intelligence work can involve offensive actions as well as information gathering. Espionage services are sometimes called to sabotage. Japanese forces attempted to turn military balloons to such ends during World War II. Per NPR, the project was developed by scientists who realized that balloons loaded with explosive devices could be sent along a Pacific air stream. If the balloons landed in the Pacific Northwest, they could cause massive forest fires that might demoralize American citizenry and cause trouble for any military activities on the west coast.

The Fugo bombs, as they were known, were made of paper and carried 33-pound bombs. They could travel to North America in a matter of days. It's estimated that 6,000 balloons were deployed during the war. The effectiveness of the campaign, however, is hard to gauge. The U.S. government prevented any reporting on the bombs, with the aim of frustrating Japanese efforts to monitor the endeavor. Two incidents in 1945 were reported: One resulted in a dead family in Oregon and the other a temporary power outage for Hanford Engineer Works in Washington state, where work was being done on the first nuclear weapons.

A good number of the Fugo balloons landed without detonating, and sightings came in for decades after the war's end. Some balloons drifted as far inland as Michigan before coming down to earth. Others came as far north as Alaska. The most recently found balloon was in British Columbia in 2014.

A reconnaissance mission with a balloon was behind the Roswell incident

A mysterious collection of debris is found in the desert, unlike any commonly known technology. Could it be evidence of visitors from beyond the stars? Or could it be a reconnaissance balloon deployed for the Cold War that went off-course? The former has excited the imagination of UFO enthusiasts for decades, and is arguably a lot more fun. But the latter is the more probable explanation for the infamous Roswell incident.

In 1947, the United States began Project Mogul, an intelligence operation designed to monitor any potential nuclear tests carried out by the Soviet Union (which, unknown to U.S. intelligence, was two years away from the bomb). According to Smithsonian Magazine, a series of large balloons armed with surveillance equipment were launched from the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico into the ionosphere, where they rode the jet stream until they reached Russian territory.

But one stray balloon never made it out of New Mexico. It crashed near the town of Roswell, was discovered by farmers who had no idea what the tin and rubber contraption was, and examined by local officials equally flummoxed. When the Air Force was alerted, they considered it more important to cover up any intelligence activities tied to the growing Cold War than to provide an honest or plausible explanation. A newspaper quoted an intelligence officer describing the wreckage as a flying saucer, and a legend was born.

Project Moby Dick

The Cold War fueled paranoias, intrigues, and sophisticated operations. Whether or not they were helpful or even plausible, the climate of the time demanded that intelligence agencies have plans and projects at the ready. One such seemingly quixotic scheme was hatched by the U.S. Air Force in the 1950s. Christened Project Moby Dick, according to Atlas Obscura, the operation required hundreds of unmanned spy balloons to be set adrift from Europe, float over Soviet territory, take photographs, and be collected in the air once they'd reached Japanese airspace.

Development of the types of balloons used in Project Moby Dick was the American military's highest priority after the H-bomb. Each balloon carried a small box loaded with camera, film, padding, and sensors to gauge altitude and manage ballast. There was also an identity card on each balloon, claiming it was a harmless meteorological instrument and that a reward would be given for its return to allied authorities unspoiled.

The U.S. recorded 448 successful launches for Project Moby Dick, but Soviet authorities were quick to notice and protest the unwelcome craft. The balloons were relatively easy to shoot down when they came into low altitudes, and the vast majority were either destroyed or crashed. The project lasted less than a month in 1956 before being called off. A handful of balloons made it back and provided useful intelligence, but the Soviets were able to gather intel of their own from the balloons that landed in their territory.

Spy balloons were used throughout the War in Afghanistan

In 2011, Wired reported that the U.S. military budget for balloons was $1 billion. As the War in Afghanistan continued, improvised bombings by insurgents were becoming a greater threat to NATO forces, and scouting tools like the Predator drone ran up a big price tag. A large investment in spy balloons would allow troops to cheaply deploy a greater number of tethered craft with mounted cameras to scope out terrain.

The use of reconnaissance balloons in the War in Afghanistan was labeled the Persistent Threat Detection Symbols program. Its funding initially came from money appropriated for military vehicles, putting the Pentagon and the House of Representatives at odds before the billion dollar budget was granted. In addition to spy balloons, the army began using decoy craft to tray and draw out insurgent fire.

Spy balloons weren't only used in combat during the War in Afghanistan. In 2009, The Washington Post reported that a single balloon with live video feed dubbed "marshmallow man" was used to monitor elections in Kabul.

China's use of a spy balloon renewed interest in 2023

Public knowledge and interest in spy balloons greatly increased in early 2023 when media outlets began reporting on the presence of Chinese balloons flying over American and Canadian airspace. According to The Guardian, neither craft was assessed to pose a danger, though flights out of Billings Logan airport in Montana were briefly suspended as one of the balloons passed over the state. China was quick to deny that the balloons were part of any intelligence operation and mocked American officials for assuming that they would use such an old technique.

The situation escalated when one of the balloons was shot down by American fighter jets. China renewed its protests against accusations of espionage. According to the BBC, they claimed that they had verified the balloon's identity as a weather ship and notified the American government of its civilian nature. They even offered an apology (via The Guardian), but the U.S. government and military remained convinced the balloon was a spy craft. A planned visit by Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to try and improve U.S.-China relations was indefinitely postponed.