Greek Mythology's Explanations For Nature

While the modern, 21st-century world definitely has a lot of perks — like Netflix, indoor plumbing, and ice cream — there's a lot that the world has had to trade to get those things. Specifically, a sense of wonder and the deeply spiritual connection our ancient ancestors had with the natural world around them. Sure, they might not have known the science behind why things were happening, but that's ok — they came up with some pretty amazing stories to explain what they were experiencing.

Ancient Greek beliefs taught that the Earth Mother was one of the oldest goddesses of all. The only thing that came before Gaia was Chaos, an empty, vast nothingness. When Gaia emerged from Chaos — along with Love and Hell — it signified the beginning of everything.

Classical Mythology says that included the creation of her male counterpart, Ouranos. When Ouranos — the sky — entered into a partnership with the earth, they produced ancients like the one-eyed Kyklopes, the hundred-handed Hekatoncheires, and the Titans, who in turn embodied the traits of the natural world ... or gave birth to the gods and goddesses who did. The result was a rich tapestry of stories, describing the sacred reasons for the natural phenomenon happening around them, and they're stories that the 21st century can still learn from and appreciate.

Persephone, Demeter, and Hades: The seasons

The goddess Demeter and her daughter, Persephone — along with Hades, god of the Underworld — have a major role in a whole series of myths, but the most famous is perhaps the ancient explanation for the cycle of the seasons. It started, says World History, when Hades saw Persephone and fell madly in love with her. Then, as the ancient Greek gods tend to do, decided to abduct her, leaving her desperate mother to search for her.

During her travels, Demeter met a particularly kind family. In exchange, she gave them the gifts of agriculture and grain, and they ultimately built her a temple. Demeter disappeared into the temple and sent a very clear message: Return her daughter, or the drought and famine she had brought down on the world would continue. The other gods decided this was about the time someone needed to step up and get involved, but since Persephone had eaten while in the Underworld, she was condemned to be Hades's bride. The result was a compromise, where she spent a third of the year with Hades, and two-thirds with her mother.

The seasons were said to change with Persephone's travels to and from the Underworld, with some rituals dedicated to reenacting Demeter's search for her daughter. Interestingly, there's a theory that her return to the surface heralded not spring, but winter: Grain was stored underground in the late summer, planted in the fall, and left to germinate over the winter — when, perhaps, she was with her mother.

The overseers of thunder and lightning

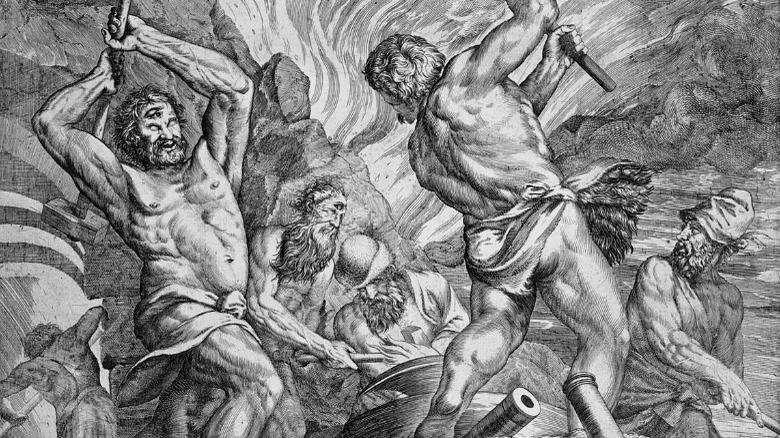

Thunder and lightning are perhaps one of the most stunning displays of the power of nature, so it's not entirely surprising that it was the domain of Zeus, the god of the sky. But even gods need a helping hand sometimes, and Zeus didn't actually create the bolts he was so commonly depicted as throwing. That was the work of a pair of Kyklopes named Brontes and Steropes.

Classical Mythology says that among those born to Gaia were the one-eyed Kyklops. Theoi notes that at their birth, their father — Ouranos, the Sky — imprisoned them deep inside the earth, where they were trapped until they were released by Zeus and his brothers. After they were given their freedom, Virgil wrote in "Aeneid" that they chose to remain inside a volcano on an island off the coast of Sicily, where they worked at their forge. It was there that they — particularly Brontes (thunder) and Steropes (Lightning) — forged the bolts that lit up the sky when they were thrown by the sky god (along with other weapons for the gods).

In later stories, the elder Kyklopes were replaced with a pair of goddesses called Bronte (Thunder) and Astrape (Lightning). According to Theoi, they fulfilled the same role, but without the origin story. As for Zeus, the lightning bolts became so important to his mythology that he was almost always depicted as holding one, and when he headed out to do battle — or throw a temper tantrum — they were carried by Pegasus.

Why do sunflowers watch the sun?

In some cases, modern science isn't too far ahead of the ancients. According to NPR, it wasn't until 2016 that researchers unlocked the process by which young sunflowers move their faces toward the sun. They found that it's twofold: The stems of still-growing sunflowers grew one side at a time to keep the flowers facing the sun, while mature flowers faced east in order to take full advantage of the morning sun.

The ancient Greeks had a different explanation, and it's a heartbreaking one. According to Ovid (via Theoi), Clytie was a nymph who had fallen madly in love with the sun, Helios. He, however, had fallen in love with another woman, a mortal Persian princess named Leucothoe. Disguising himself as her mother, he snuck into Leucothoe's chambers, revealed himself, and had his way with her.

Clytie made sure everyone knew about it, but after Leucothoe's father ordered her execution, Helios scorned Clytie completely and thoroughly. For nine days, Clytie knelt, mourned, and looked to the sky to watch her beloved cross above her; she was transformed into the sunflower, condemned to watch Helios travel his route across the sky for the rest of eternity.

Where do echoes come from?

The nymph Echo's name is derived from the Greek word for sound, and according to The Collector, it was appropriate. Echo loved to talk, and unfortunately for her, she was recruited by Zeus to distract Hera — his wife — from his many, many affairs. When Hera caught on, she took away Echo's ability to say anything beyond the last words she heard.

It was after this that Echo met the beautiful Narcissus. She fell madly in love with him, but he was horrified when they came face-to-face, with her only repeating what he said. Telling her that he'd die before returning her affection, she fled into the woods and wasted away into nothingness. The only thing left was her voice, but there's a little bit of karmic justice here. Echo was widely beloved, and Narcissus's cruelty toward her got the attention of the revenge goddess Nemesis. She felt a fitting punishment would be to have Narcissus fall in love with his own reflection, since he was most of the way there anyway. He did — unable to touch or feel the reflection he loved so much, he wasted away and was transformed into the Narcissus flower.

A second version of Echo's story is no less sad. In this one, she has such a beautiful singing voice that the god Pan — outraged that such an incredible voice is wasted on a nymph — sends bloodthirsty animals to attack and kill her. The earth goddess Gaia, however, preserved Echo's voice, and it can still be heard today.

Iris, the Rainbow

Today, science is familiar with the weather patterns that result in a rainbow arcing across the sky. Ancient Greeks, too, noted the circumstances in which a rainbow tended to appear, and told the story of a divine messenger whose path was marked by the rainbow.

Her name was Iris, and she was the daughter of a sea god and a cloud nymph. In addition to being Hera's personal messenger (along with sometimes appearing alongside Zeus and Achilles), she was also said to have been tasked with refilling the rain clouds as they drizzled: She would travel from one end of the rainbow — which often appeared to end in the seas around Greece — up into the clouds. There are — unsurprisingly — a few different versions of her stories. In some, the rainbow is a road that she lays out before her in her many travels between gods and men, and when it vanishes, that means she's passed (via Theoi).

Greek mythology explains the rare phenomenon of the double rainbow as well. It was said that Iris had a sister named Arke, and when it came time for the gods and the Titans to go to war, they ended up on opposite sides. Iris served the ultimately victorious gods, while Arke lost her wings (which were eventually given to Achilles). The rare, always faded, second rainbow is all that's left of the goddess that chose to be on the wrong side of a divine battle.

The storm-winds

Modern imagery — particularly in video games — depicts the Harpies as monstrous creatures that are half-bird, half-woman. While Theoi says that they were depicted as such in Greek mythology, there was a little more to the story. The Harpyiai were spirits that answered to Zeus, could be sent to earth on a whim, and were heralded by sharp, strong gusts of wind that seemed to come out of nowhere. Their travel explained the winds, but it was also used to explain any mysterious, unexplained disappearances: When someone seemed to simply drop off the face of the earth, it was often said they had been taken by the Harpyiai.

They weren't the only personification of the storm winds, though: They also had male counterparts (and in some versions, brothers) called the Anemoi Thuellai. They were the offspring of the storm-giant Typhoeus, who Zeus had defeated and condemned to Tartaros. Initially sent by the giant to create all sorts of problems for humankind, Zeus captured them in a giant bag made from the skin of an entire ox. He gave the bag to a king named Aiolos, who would release the winds when the gods needed a little bit more destruction. (Odysseus's crew opened the bag at one point in their travels, unleashing a massive storm that pushed them even farther from home.)

The winds

The ancient Greeks differentiated between good and bad winds — and anyone who's ever cursed at a storm and enjoyed a breeze on a hot summer's day can see why. While the storm winds were destructive forces unleashed for varying degrees of vengeance, the good winds were said to be embodied by four young men. Theoi says those were the North winter wind (Boreas), the South summer wind (Notos), the West springtime wind (Zephryos), and the East wind (Euros). Four other winds were also given identities and roles: The North-west wind, for example, was called Skiron, and he was said to spill wind from a cauldron to bring about the first traces of winter.

The winds show up in a series of different myths and stories. When Achilles struggled to light the funeral pyre of his beloved Patroclus, a prayer to the West wind, Zephryos, sorted things out. They also appeared at the funeral of Eos's son, Memnon, and escorted his mortal remains to their final resting place. They even attended the funeral pyre of Achilles himself, to make sure the fire burned hot and long.

While black lambs were often sacrificed to appease the storm winds, white lambs were gifted to the good winds. Through their offspring, their influence reached even farther: They were said to be the fathers of a group of immortal horses who drew the chariots of the gods. In Zeus's case, though, the four winds took the shape of horses to pull his chariot themselves.

Tsunamis and earthquakes

Poseidon was famously the god of the sea, but according to World History, both Hesiod and Homer refer to him by the descriptor "deep-sounding Earth-shaker." While that sounds like a bit of a stretch, it's actually right in line with ancient Greek beliefs. They taught that water covered the world in its entirety, and that all land was floating on top of it. When Poseidon got angry, the whole earth trembled — and what goes along with earthquakes? Tsunamis.

Aeon says that Greece is a seismologist's wonderland, and it always has been. In 373 BC, the island of Helike was completely destroyed in a two-fold catastrophe: First, an earthquake destroyed most of the buildings on the island, and then a tsunami washed everything away. The idea that Poseidon was behind this all was an old one: As early as 700 BC, the writings of Homer described a sea god furious that Greek cities had tried to protect their ships from the wrath of the sea by building a wall. That worked out about as well as could be expected.

The connection between earthquakes, tsunamis, and the wrath of Poseidon was so great that he was actively worshiped for more than 1,500 years. Stories of Poseidon defeating entire armies are laid out in history books, delivering a powerful lesson about the necessity of respecting the power of nature.

The cold north wind and snow

The Anemoi may have represented the more benevolent of the winds, but one in particular — the North winter wind — was, well, a bit of a jerk. According to World History, Boreas was the personification of the winds that brought the cold, that knocked down trees, and chilled animals and humans alike in that special sort of way that cut right to the bones. While Boreas shows up in numerous myths — including the birth of the twins Artemis and Apollo — he's perhaps best known for his abduction of a mortal princess named Orithyia.

Initially, Boreas asked Orithyia's father for permission to marry her, but when things didn't progress as fast as he liked, he swooped in and literally carried her away to his home in the mountains north of Greece. It was there that she was not only given immortality, but that she became associated with a particular kind of northern wind, says Theoi: understandably, the really, really cold, bitter ones that came from the mountains.

The union of Boreas and Orithyia produced several children, including Khione. She, too, was divine, and became known as the goddess of snow.

Volcanos, hot springs, and geysers

Britannica says that Mount Etna has been active for somewhere around 2.6 million years, give or take. Eruptions — and the threat of eruptions — happened throughout the ancient Greek world, and there are several mythological explanations given for it. Some believed that it was the site of the forge of the god Hephaestus, while others said it was the home of a goddess named Aetna and the giant, Typhoeus.

Aetna was originally a nymph who had intervened when Demeter and Hephaestus began to argue over who would be the patron of Sicily. By this time, Zeus had condemned Typhoeus to imprisonment there, and according to one version of the story, Aetna lived there as the mother of several of Hephaestus's children, and the guardian of the giant. Her massive form kept him imprisoned, and the occasional lava flow happened when he started to move.

She also gave birth to a group of gods called the Palikoi, who were fathered either by Zeus or Hephaestus. According to Theoi, the twin gods were the embodiment of hot springs and geysers, and they were born directly from the earth after their mother prayed for protection from the gods. The gods were said to be closely tied to the springs, and directly responsible for answering prayers and enforcing oaths sworn to them.

The dangers of the deep

There's one part of the natural world that modern science isn't very far ahead in, and that's the ocean. According to UNESCO, the amount of the ocean that's been thoroughly mapped is only equivalent to about 5% of the entire thing, and that means there's a lot we don't know about. The ancient Greeks knew there was a lot they didn't know either, and their explanation for all the terrifying things hidden in the depths was an ancient deity called Phorkys.

Phorkys, says Theoi, was often depicted as being an older man, who had a mermaid-like tail with sets of crab claws along the length of it, and the hard skin of a crab. In addition to watching over all the creatures in the secret depths of the waters, he also fathered a lot of them.

That included the two (or three) crone-like personifications of sea foam, the Graiai. Always ancient, they were a set of sisters who had one eye and one tooth to share between them. There were also the Gorgones, with the most famous of those sisters being the only mortal one, Medusa. He also fathered the monsters Ekhidna and Drakon-Ladon, and while sailors might not have expected to run into either of them while they were out in the open waters, Phorkys was also said to be a grandfather (of sorts) to a very real danger: whirlpools. His daughter, Skylla, was a 12-footed, six-headed, fish-tailed monster who created whirlpools in her wake.

The seasons and the reliable progression of time

No matter how terrible — or good — a day is, it'll gradually come to an end. The sun will set, and inevitably, it'll be back up to welcome another stupid day. Greek mythology said that the progression of time — from hours to days to months to seasons and years, to the movement of the constellations through the sky — was overseen by a group of goddesses called the Horai.

The sisters of the three Fates, the Horai, were originally responsible for maintaining order in the natural world, although Theoi says that their domain gradually expanded into all order and justice. The number of Horai varied between "three" and "many," with three main sisters being identified with the pasture, spring, and justice. Others included goddesses associated with prosperity, substance, growth, and each individual season.

Among the many daughters of Zeus, the Horai were seen as guardians that made sure everything kept running as it should — and they acted as guards for Olympus and the heavenly afterlife. Philostratus the Elder wrote on just how important they were, saying that the sweetest, most fertile lands were said to have been touched by the goddesses themselves. In other versions of the stories, they were the daughters of the sun god, Helios, who worked on earth and alongside their father's route through the skies.